THE FIGHTING CIRCLE

Gladiatorial combat in the AD&D®

game

by Dan Salas

THE FIGHTING CIRCLE

Gladiatorial combat in the AD&D®

game

by Dan Salas

| - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | Dragon 118 |

The battlefield’s hot

sands were stained

red under the afternoon

sun. Ignoring the

heat, Arius Caldia fought

to keep his vision

clear and his legs steady

He was at the

limit of his strength.

His head swirled with

dizziness, and his chest

was soaked with

blood and throbbing with

pain.

Despite his

agony, Arius somehow

managed to stay on

his feet.

The roar of 30,000 people

rang in his

ears. Half-blindly, he

scanned the rows of

shouting, cheering spectators

that encir-

cled the

small battlefield. Arius felt disgust

and hatred for them.

He knew that they

would probably not be

satisfied until he

joined the two warriors

whom he had just

fought. Both men now

lay dead on differ-

ent sides of the arena,

victims of the audi-

ence’s cruelty and of

Arius’ bloodstained

short sword.

Just as he was beginning

to hope that

the duels were finished,

an iron door slid

open at the far end of

the circular pit. A

huge fighter stepped

into the sunlight. The

audience howled with

renewed excite-

ment. Arius looked with

despair at his

new enemy — tall and

bearlike, head and

face hidden in a thick

metal helmet, left

side covered by a large

rectangular shield,

and a short sword gleaming

in his right

hand.

Arius’ heart was almost

as heavy as his

exhausted arms. He knew

that he could

not win another duel,

especially against

such a formidable opponent.

All he

wanted was to die quickly

and painlessly,

and to be remembered

as a courageous

warrior. His vision blurred

and he pa-

tiently waited for death.

Suddenly he heard a tigerish

snarl. He

opened his eyes to see

the other warrior

charge like a battering

ram, sword raised

high. The weapon lunged

toward Arius’

throat, but the smaller

man instinctively

knocked it aside with

his own blade. His

mind sharpened, his body

tensed, and he

returned a vicious cut

that sent his oppo-

nent staggering back

in surprise and fear.

Swords clashed again

and again in the

arena, and the crowd

cheered on. . . .

Gladiatorial combat can fit

easily into

any fantasy game world.

Though this

article is designed for

use in the AD&D®

game, its rules are adaptable

to most role-

playing game systems. Any

character can

stage armed combat in a

village or castle,

but these rules were created

on a scale

equal to the glorious games

of ancient

Rome.

Historical gladiatorial contests

first be-

gan with the Etruscan custom

of forcing

slaves to fight to the death

in funeral

ceremonies. This insured

companions for

an important person in the

afterlife. The

Romans adopted this practice

in 264 B.C.,

when three pairs of slaves

battled at the

funeral of Brutus Pera.

From these grim

beginnings, the combats

became a specta-

tor sport in arenas all

over the Roman

Empire. The earliest “games”

were often

slaughters rather than actual

fights, in

which victims were tied

helplessly to posts

and devoured by leopards.

But the main

attraction became armed

combat between

two fighters. Several attempts

were made

to suppress the bloody spectacle

of the

arena, though none succeeded

until A.D.

500.

The alignment and social

attitudes of a

society must determine whether

or not

that society condones gladiatorial

sports.

Naturally, no good-aligned

people enjoy

watching fights to the death,

as only a

warlike race admires fighting

skills. The

Romans fit well into these

restrictions.

Their preference bordered

on sadism,

especially when helpless

victims were fed

to starving animals or when

animals were

slaughtered in combat with

specially

trained fighters. This article

avoids discus-

sing the murderous aspects

of the arena

and concentrates on the

person-to-person

fighting that was involved.

Gladiatorial fighting is

a male-dominated

sport. For simplicity, this

article uses

words such as “he” and “him”

instead of

“he/she” and “him/her.”

However, female

players need not take offense.

Women

gladiators were a rare but

popular addi-

tion to the games of ancient

Rome, and

female PCs are as welcome

in the arena as

their male comrades.

Before holding any games,

it is necessary

for the DM to choose between

one of

these campaign settings:

1. Classical Roman. This

is the setting

upon which most of the article

is based,

since ancient Rome was the

only civiliza-

tion which fully developed

gladiatorial

combat.

2. Medieval. This setting

is more like a

typical AD&D

game setting than the classi-

cal campaign, since the

AD&D game is

based on medieval European

history.

Medieval games will be dealt

with in detail

later.

3. Oriental. This setting

is designed for

use with Oriental Adventures.

Oriental

games are dealt with in

detail later.

It would be unwise for a

DM to mix

these settings because of

the differences

between them. For example,

classical

gladiators are at a disadvantage

because of

their less damaging weapons,

and Oriental

gladiators are at an advantage

because of

the use of their ki power.

There are al-

ready enough variations

within each set-

ting to keep players occupied

without the

necessity to mix campaign

settings.

It is interesting to note

that the blood-

shed and carnage of the

classical Roman

gladiatorial competitions

were eventually

replaced in the Middle Ages

by the equally

combative, though less lethal,

tournament

competitions. In turn, this

competition has

nearly disappeared from

modern society

(except in the form of fencing,

wrestling,

football, boxing, auto racing,

and other

sports of relative tame

comparison). In the

Far East, gladiatorial competition

never

made an appearance; the

forms closest to

gladiatorial competition

in which these

cultures indulged in were

public matches

held between rival martial

arts schools.

These competitions rarely

resulted in

lethal combat; the matches

were per-

formed more for display

and for education

than for commercial entertainment.

In

present Oriental societies,

tame examples

of these competitions exist

in the form of

martial-arts tournaments,

sumo wrestling

matches, and kendo competitions.

Of

course, the ultimate decision

as to

whether or not a campaign

culture enter-

tains itself with gladiatorial

competitions is

up to the DM.

Most gladiators (in a fantasy

campaign

that parallels the classical

Roman setting)

are slaves, criminals, and

prisoners of war.

Instead of labor slavery,

imprisonment, or

execution, they are enrolled

in gladiatorial

schools for lengthy training,

after which

they are sent into the arena.

The fame and

fortune offered by the games

even attracts

free characters into the

duels.

Only combative classes are

suitable for

the arena. These include

cavaliers, fight-

ers, thieves, monks, and

their sub-classes.

Merciful DMs use noncombative-class

captives for other purposes,

since any

class not mentioned above

has little

chance of survival in the

pit.

Also, the alignment of a

PC or NPC

should be considered before

any fighting

starts. Lawful-good characters

refuse to

fight for the enjoyment

of a sadistic audi-

ence, and such characters

are more likely

to attempt an escape or

die before aban-

doning their beliefs. Other

good align-

ments allow gladiatorial

duels only when

there is no other choice.

All non-good

characters are free of these

restrictions.

It is the goal of every

enslaved gladiator

to fight his way to liberty.

After three

years of arena experience,

a gladiator

receives a ceremonial wooden

sword in

his last forced game. This

sword is given

by the game’s official in

front of the cheer-

ing audience; it signifies

the warrior’s

discharge from gladiatorial

service. Some

of these characters become

trainers, while

others are put into jobs

such as laboring,

serving, guarding, and soldiering.

Once per year after two

more years,

each gladiator rolls a 1d20

Charisma

Check to attempt to be freed

by his owner.

Those who fail the check

must remain in

slavery for another year.

Though not

considered citizens, freed

men are of the

lower-lower social classes.

Freed gladiators are sometimes

offered

1,000 gp by a game’s official,

with the

obligation to enter the

next event as a

champion. Whether the fighting

consists

of duels or massed battles,

it is the gladia-

tor’s choice to join or

refuse.

Famous gladiators receive

the favor of

the people. They are treated

as aristocrats

in some cases, drawing the

respect of the

soldiers and, for men with

decent cha-

risma and comeliness scores,

the love of

young women. Some ex-gladiators

become

honored officers in the

military or expen-

sive bodyguards for top

politicians.

Training

schools

Since most gladiators are

criminals and

war prisoners, training

schools resemble

detention camps, complete

with plenty of

shackles, armed guards,

and high, barri-

caded walls. Here, the prisoner-gladiators

live, eat, sleep, and practice.

Discipline is

strict, and punishments

are severe. When

not in use, all weapons

and armor are

locked in an armory and

carefully

guarded.

Schools are owned either

by the govern-

ment or by private individuals.

The chief

manager is called a lanista.

He oversees

the work of the school’s

employees, admin-

isters its business, and

he occasionally

(20% chance) owns it himself.

There is a

30% chance that he is an

experienced

gladiator (8th- to 11th-level

fighter).

A player character can open

a training

school for profit. First

a school must be

bought or built. This costs

100 gp per

gladiator to be housed and

trained. Next,

equipment must be gathered.

The total

cost of equipping a school

with weapons,

armor, kitchen utensils,

furniture, etc., is

50 gp per gladiator to be

housed. If an

equipped school is bought,

add both of

these fees together for

the final price.

The school can now be opened.

Crimi-

nals must be bought from

the prisons and

given instruction in the

fighting arts. In a

good-sized fantasy city,

about 3-18 suitable

men are available for sale

per month,

costing d20 + 20 gp each.

Running a school costs the

owner 20 gp

per untrained gladiator

per month. A

trained gladiator costs

15 gp per month.

These expenses cover the

hiring of train-

ers (5th-8th level fighters),

guards (lst- and

2nd-level fighters), doctors,

accountants,

servants, and cooks, and

also covers the

buying of food and equipment.

After training is complete,

the school

can sell the unfree warriors

for 300 gp per

level or rent them for 20

gp per level, per

duel. Rented gladiators

who die cost the

renter 300 gp per level;

this is the total

price and is not added to

the rent fee. Free

characters pay 300 gp for

training, must

remain on the grounds only

during train-

ing hours, and are not subjected

to the

harsher aspects of the school.

To receive monthly income,

follow these

three steps:

1. There is a 5% chance

for every 10

gladiators that the school

trains that a free

character enrolls in the

school. This brings

an income of 300 gp.

2. Each month, 50% of the

school’s

trained gladiators are rented

out and

brought back alive. This

brings an income

of 20 gp per level of each

character.

3. Each month, 40% of the

school’s

trained gladiators are sold,

either living or

as rented fighters who died

in the arena.

For schools that are renting

only, 30% of

its gladiators are killed

while rented. This

brings an income of 300

gp per level of

each gladiator.

As with modern businesses,

it takes a lot

of money to start a school.

Characters will

not see the profits until

after a few

months, but when the initial

payments are

passed, the income grows

quickly. School

owners are advised to buy

untrained

criminals whenever possible

and to buy

trained gladiators only

when necessary.

Counting only monthly upkeep

costs, 240

gp are spent in putting

a zero-level pris-

oner through training, while

it costs 300

gp to buy a lst-level gladiator.

The 60 gp

difference is quite large

when multiplied

by the number of gladiators

that can be

involved in a school.

DMs need to record the level

of each

gladiator, especially when

characters buy

trained prisoner-gladiators

in order to rent

them to other characters.

All untrained

NPCs are zero-level fighters,

and all

recently-trained gladiators

are 1st-level

fighters. For level advancement,

award

each NPC gladiator 25 experience

points

per month.

Classical

styles

Classical gladiators are

divided into

several different fighting

styles (not

classes). Each style has

its own equipment

as described below. Armor

is barely used

because the gladiators are

expected to be

schooled in defensive techniques

which

would alleviate the need

for heavy protec-

tion. In addition to the

equipment listed,

many of the gladiators wear

leather armor

on the right arm from shoulder

to wrist.

In each duel, a gladiator

has a 20% chance

of receiving this extra

armor. [A partial-

armor combat system useful

for this situa-

tion appeared in DRAGON®

issue #112:

“Armor PIECE BY PIECE,”

by Matt Bandy —

RM]

A retiarius is a warrior

who wears only

a short tunic. He uses a

net and trident in

combat.

A thrace wears a greave

(a metal shin

guard) on the left leg (armor

class 4 for

lower leg only), and carries

a buckler

shield. In one hand, he

wields a dagger.

A dimachare wears one greave

and

carries a short sword in

each hand. For

this warrior, use the rules

for fighting

with a secondary weapon

described in the

Dungeon Masters Guide.

A secutor carries a large

shield and

wears a large helmet with

visor. He uses

the best weapon of the Roman

arena: the

gladius, or short sword.

This was also the

favorite weapon of the Roman

army.

A mirmillo is equipped similarly

to a

secutor, except that mirmillones

have a

metal fish on the crests

of their helmets.

A samnite is equal to a

heavy infantry

man. He wears a large helmet

with visor

and one greave. He carries

a large shield

and a short sword, and he

has a 30%

chance per duel of being

allowed to wear

banded mail armor.

A hoplomache is a samnite

who has

reached 5th level. Both

are equipped simi-

larly, except that a hoplomache

has a 60%

chance per duel of wearing

bronze plate

mail. The change of armor

is a symbol of

status.

Training procedure

In the schools, gladiators

train for one

full year before entering

the games. This

insures a good knowledge

of weapon skills

and a willingness to give

a good fight. All

students must practice for

seven hours a

day, six days a week. Any

time missed

must be made up before training

is

complete.

The first stage of training

consists of

exercises using wooden weapons

against

wooden posts. At this time,

gladiators are

watched closely by the trainers,

who then

select the style that best

suits each trainee.

Roll 1d20 on Table 1 for

each PC and NPC,

as necessary. Since the

trainers are ex-

perts in arena combat, they

do not accept

changes in these decisions.

Displeased

freemen can leave if they

want, but their

payment will not be refunded.

From this point, the trainees

practice

sparring with wooden weapons

and, even-

tually, with real weapons.

They learn how

and where to strike, how

to put on a good

show, how to call for mercy

from the

audience, how to die honorably,

and other

important matters.

Students become proficient

with the

short sword and dagger,

or the net and

trident. If no proficiency

slots are open,

use slots that have not

yet been gained by

level advancement. Thus,

either one or

two of the upcoming slots

will already be

filled when the character

reaches the next

level.

At the end of the year,

zero-level gladia-

tors become 1st level, and

all others re-

ceive 1,000 experience points

per level at

the start of training. Every

graduate re-

ceives a scroll stating

the gladiator’s name,

the name of the school,

and the date of

issue. Free characters can

then pursue

their careers at will, while

other charac-

ters are rented out by the

school or sold to

the state or private businessmen.

The arena

Many days before the games,

posters are

set up everywhere to announce

the time

and place of the event,

the official sponsor,

the number of gladiators

participating,

and the types of combat

to be seen.

The games are usually held

in a circular

building called an amphitheater.

This huge

structure is set up in a

city or large town

where there are enough spectators

to

support the event. The center

of the build-

ing is the arena; its floor

is covered with

sand to absorb blood. This

area is often

150-200’ in diameter. Around

the pit, the

stands rise in progressively

higher rings of

seats. The official’s platform

overlooks the

entire seating area as well

as the arena.

Under the stands are corridors

and stair-

ways for the spectators,

a locked and

guarded armory, business

offices, guard

rooms, stables, chambers

for the gladia-

tors, and animal cages with

gates that

open into the arena.

The largest amphitheaters

can hold

50,000 people. The safest

ones are built of

stone, since wooden structures

occasion-

ally collapse under the

weight of the

crowd and kill most of the

people inside

(as actually happened in

Roman times).

The cost of admission ranges

from 1 gp

for upper-level seats to

20 gp for seats

closest to the arena. State

officials and

important nobles always

hold the best

seats. Above them sit the

wealthy aristo-

crats, and higher up sit

the common peo-

ple. Armed soldiers keep

an eye on

everything; rowdy or arrogant

spectators

risk being thrown into the

pit to face wild

dogs and lions. Roman-style

soldiers have

bronze plate mail, large

shields, spears,

and short swords.

The games begin with a blare

of trum-

pets and a parade of the

gladiators, who

dress in colorful cloaks

and ceremonial

armor of gold and silver.

They pause be-

fore the sponsor, raise

their right hands in

salute, and shout, “Hail

from men about to

die!” Soon, nonlethal duels

with wooden

weapons get things rolling.

At a signal

from the trumpets, warriors

are called up

from the waiting cells for

deadly combat.

Cowards are “inspired” by

whips and hot

irons. Solitary duels dominate

most of the

event.

In a Roman variation, the

morning is

spent in wild-beast fights,

which include

human victims and human

opponents. At

noon, there is an intermission.

Spectators

leave for lunch or stay

to watch the grue-

some executions of prisoners

not suitable

for gladiatorial status.

In the afternoon

comes the parade of gladiators,

and the

real games begin.

The DM must randomly choose

the

number of participants in

this game. This

decision should be influenced

by the popu-

larity of the games, the

population of the

area or city, the size of

the amphitheater,

and the wealth of the sponsor.

One hun-

dred duels are common, while

Roman

Imperial game contained

5,000 and even

10,000 duels.

Around 20 duels can be staged

in one

day. This limit gives an

average time

length of 10 rounds per

duel, with five

rounds between fights for

collection of

bodies and the preparation

of the next

gladiators.

Wealthy PCs can sponsor

their own

events to gain popularity

and gold pieces.

DMs need to decide the cost

of renting (or

building) an amphitheater,

the price of

announcing each event, and

the cost of

hiring guards and servants.

Other figures

include the number of gladiators

who

participate and the number

of spectators

who watch. Income is gathered

in the

form of admission prices,

and gold must

be given to the winners

and owners of

winners of the duels.

Victorious army commanders

occasion-

ally have plenty of war

prisoners to fight

in the gladiatorial games

— these prisoners

can be bought from an NPC

commander

or used directly by a PC

commander. In

either case, the gladiators

receive no pay-

ment for their successes

and therefore are

a good investment.

Gladiators are chosen by

lots in front of

the crowd and called out

one by one into

the pit. Free gladiators

can enter as many

duels as they want. Prisoners

are usually

forced to fight only once

during an event.

Sometimes a hated criminal

is condemned

to fight two or three consecutive

duels

(this is considered an execution

rather

than fair fighting).

A retiarius, thrace, or

dimachare who

fights in a style in which

he has not been

properly trained suffers

a penalty of -2 to

hit. The other styles can

be interchanged

freely, unless they fight

in one of the three

styles mentioned above,

in which case the

penalty is used. Gladiators

are proud of

their own styles and do

not like to stray

from these fighting techniques.

There is only one way to

win a duel:

battle the enemy until he

surrenders or

dies. Normal melee combat

rules are rec-

ommended for PCs, but if

the DM wishes

to resolve the duel more

quickly (espe-

cially when matching two

NPCs against

each other), the combat

resolution system

detailed later should be

used.

Knowledgeable fighters use

every tactic

available to them in a duel.

This helps to

avoid a typical hack-and-slash

game.

Lower-level gladiators especially

should

avoid this type of attritional

combat.

A warrior with an entangling

weapon

can attempt to wrap it around

his oppo-

nent’s weapon arm (and the

opponent

then attacks at -4 to hit)

or to grasp the

man’s leg and unbalance

him (the entan-

gler attacks at +2 to hit

and the held

opponent attacks at -2 to

hit). If the

entangler tugs on the weapon

for an attack,

his opponent must pass a

1d20 Dexterity

Check (rolling his dexterity

or less on

1d20) or fall to the ground).

A successful

hit is necessary in either

case. Anyone

entangled by a net, whip,

or chain must

pass a 1d20 Dexterity Check

to pull him-

self free. A character entangled

by a lasso

must pass a 4d6 Dexterity

Check to pull

himself free. An entangled

character can

cut a whip, net, or lasso

by rolling +2 to

hit with a sharp weapon

and doing 3 hp

damage to the entangling

weapon.

Appendices Q and R of Unearthed

Arcana give some useful

tactics for the

arena. Grappling and overbearing

tech-

niques are useful to gladiators

with high

levels and good dexterity,

though weapon-

less combat is obviously

very dangerous

against sword-wielding foes.

Disarming

attacks are recommended

to all gladiators.

A major attraction for the

spectators is

their participation in the

games. This

occurs when a gladiator

holds up one

finger to signal defeat

and put himself at

the mercy of the crowd.

Any combatant

who feels that he cannot

win the fight due

to outmatched skill, loss

of hit points,

or an undesirable position

(such as flat on

his back with a trident

at his throat) can

use this option. By the

rules, the victorious

man cannot attack unless

he is given the

signal by the game’s official

sponsor.

Now the spectators either

wave their

handkerchiefs in the air

to demand mercy

or point their thumbs downward

to de-

mand the loser’s death (Table

2 determines

this reaction). For the

modifiers, courage

can be shown by putting

all of one’s ef-

forts into a vigorous series

of attacks,

never pausing unless absolutely

necessary,

and showing willpower and

ferocity at all

times. Attacking in every

round of the

duel is a good example.

This bonus does

not apply if the fallen

man had a strong

advantage over his victor,

such as a heavily

armored fighter against

a dagger-wielding

criminal. Cowardice is shown

by display-

ing nervousness or hesitation,

or by not

giving a good fight because

of too much

interest in one’s own life.

Anyone who acts

too miserably, such as begging

or running

in fear, automatically receives

the crowds

disapproval.

Player characters in the

stands can

influence the audience’s

decision by shout-

ing their own opinions before

anyone else.

If they do this, add one

point to the roll if

the PCs call for mercy or

subtract one

point if they call for death.

The sponsor of the game

now makes the

final decision. Roll again

on Table 2. Ignore

the modifiers listed there

and roll again if

there is a mixed decision.

New modifiers

are +8 if the crowd wants

mercy, -8 if

the crowd wants an execution,

and +6 if

the sponsor is renting or

owns the gladia-

tor in question. If death

is the man’s fate,

then he must submit honorably

to a single,

mortal strike from the victorious

fighter.

Dead gladiators are picked

up by attend-

ants after each duel. These

attendants use

hot irons (1-3 hp damage)

to check the

fallen man’s condition.

A feign death spell

may deceive them, but anyone

using raw

courage to pretend death

must pass a 6d6

Constitution Check or draw

back in pain.

Those who fell during the

fight can be

carried away alive, but

the attendants

carry hammers to finish

those who were

condemned to death by the

sponsor.

Choosing an opponent

To find an opponent for

a PC (or NPC),

follow these three steps:

1. If a known PC or NPC

is participating

in the same game as the

PC, there is a

chance that they will be

set against each

other. To get this percentage

chance, di-

vide 100 by the number of

gladiators

participating in the event

and ignore any

chances below 1%. For example,

Arius and

Drago are hated enemies

who are both

fighting in the same game.

If 100 men

participate in the event,

there is a 1%

chance these men will be

matched in the

pit. If 20 warriors fight

in another event,

the chance increases to

5%.

2. If the above roll does

not provide an

opponent, then the gladiator

has a 5%

chance per level of facing

a champion, Roll

this chance for each duel.

Use Tables 3 and

4 to determine the style

and class of the

champion. Use Table 5 (not

Table 3) for

this gladiator’s class level.

The minimum

level for a champion is

fifth. This NPC also

has modified ability scores

(to racial maxi-

mums): +3 strength, +2 dexterity,

and

+3 constitution. These bonuses

are

awarded because of the warrior’s

proven

toughness and deadliness

in the arena.

There is little chance that

an 18th-level

PC will meet an 18th-level

NPC every other

duel. It is more likely

that several lower-

level NPCs will gang up

on the PC. For this

reason, there is a 75% chance

that each

time a champion is chosen

for a character,

there will be more than

one average-level

gladiator as an opponent

rather than one

high level opponent. In

this instance, use

one NPC gladiator per five

of the charac-

ter’s levels. These are

average NPC gladia-

tors, not champions, and

are thus rolled

up on Tables 3 and 4.

3. If no opponent has yet

been chosen

for the PC, then roll up

an average NPC

gladiator on Tables 3 and

4. Note that

Table 4 gives the probable

cause of the

NPC’s participation in the

games. In most

cases, the gladiators are

enslaved. In classi-

cal games, a retiarius is

usually matched

against a mirmillo, and

a thrace is usually

matched against a secutor.

Combat resolution system

For quickly determining

the outcome of

a one-on-one duel, roll

1d20 for each com-

batant. Modifiers to the

rolls are listed on

Table 6. Bonuses are awarded

for high

physical ability scores,

ability level, and

fighting styles.

The warrior who gets the

higher score

wins. A natural roll of

1 means automatic

failure and a natural roll

of 20 means

automatic success. Reroll

all ties unless

both combatants roll a natural

1 or a natu-

ral 20. If both fighters

roll a 1, then both

roll again; neither has

a chance to ask for

the crowds mercy. If both

combatants roll

a 20, they have both given

a good show,

and are both considered

winners.

The loser’s chance to try

for mercy

equals his charisma times

two. If he rolls

this chance or less on 1d100,

then use the

normal rules for determining

the audi-

ence’s and the sponsor’s

decisions.

If necessary, check the

physical condi-

tion of the winner and the

surviving loser

after the fight. Using Table

7, roll 1d10

twice, assigning the higher

roll to the

winner, the lower to the

loser. Ties are not

re-rolled; the numbers are

assigned as

normal. If the winner has

a higher level of

ability than the loser,

subtract the differ-

ence between the two from

the loser’s die

roll. If the loser has a

higher level of abil-

ity than the winner, subtract

this differ-

ence from the winner’s die

roll. If the two

are equal in level of ability,

the die rolls

stand unmodified. Reference

these final

figures on Table 7 to determine

each char-

acter’s final physical condition.

If the loser

has been killed in combat,

the DM rolls

only for the winner, determining

his physi-

cal condition as described

above. The

percentages of hit points

indicated are

applied to each character’s

actual hit

points at the start of the

duel, not to his

maximum hit points. This

takes into ac-

count any hits received

in combat per-

formed earlier that day

or earlier that

week.

Rules of the game

It is possible for a PC

to devise a seem-

ingly perfect scheme to

cheat the follow-

ing rules of the arena.

However, no one

should be allowed to fool

the system with-

out great risk and eventual

doom. DMs

can create many ways to

foil the player’s

plans; it should be noted,

however, that a

change in the situation

which throws new

challenges at the players

is better than an

iron fist that simply crushes

their

schemes.

Punishments for breaking

the rules must

be decided by the DM, based

on the align-

ment of the sponsor and

the intensity of

the crime. Punishments can

be as merciful

as expulsion from the event

or as severe

as lifting the gates of

the animal cages and

releasing starving lions

into the arena with

the offender. Also, enraged

gladiators do

not hesitate to use their

fists or their

weapons. Against more dangerous

and

powerful offenders, DMs

can use the

soldiers who patrol the

amphitheater and

guard the game’s sponsor.

The following rules apply

to all cam-

paign settings unless stated

otherwise.

1. Equipment. No one is

allowed to bring

their own equipment into

the pit. From

the armory in the amphitheater,

gladiators

receive free use of any

armor and weap-

ons appropriate to their

style. Characters

who have not received training

in a style

can choose one piece or

set of armor: (1) a

large shield, (2) a large

helmet with visor,

or (3) a buckler shield

and small helmet.

They can also choose one

type or set of

weapons: (1) a dagger, (2)

a whip, (3) a

lasso, (4) a short sword

or swords, or (5) a

net and trident. After the

games, all equip-

ment must be returned to

the armory;

free characters can regain

their own

equipment after that.

2. Payment. Free gladiators

and pris-

oners’ owners receive gold

for the victo-

ries in the duels. To determine

the exact

payment, multiply the defeated

character’s

level by 15 gp. The total

for the day is paid

at the end of each game

day. The money

goes to a prisoner-gladiator’s

owner even

if the gladiator later dies

in the arena. If a

free gladiator dies before

collecting his

pay, the gold stays in the

amphitheater

treasury.

Payment is not given to

participants of

massed battle games because

it is impos-

sible to determine who has

killed whom.

For this reason, few prisoner-gladiator

owners enter their men into

such games;

free men almost never do.

Massed battles

are therefore fought mostly

by untrained

criminals and war prisoners.

3. Magic. Spell use in gladiatorial

combat

is extremely rare. Most

gladiators are

simply professional fighters

who take

pride in their skills, and

magic can easily

ruin their chances of survival.

Anyone

caught using spells or magic

items draws

the wrath of dozens (or

hundreds) of

angry gladiators. Also,

the audience pays

to see the fighting skills

of the gladiators;

thus, magic is considered

an unfair advan-

tage that deflates the thrill

of the game.

This is why all armor and

weapons used in

the pit must come from the

amphitheater’s

armory.

Any use of magic is a dangerous

act. If

someone attempts to cast

a spell in the

arena, there is a good chance

that he will

be noticed. Invisibility

and fireball spells,

for example, are obvious.

If a rule-breaker

is more subtle (such as

using a bless spell,

a heal spell, or a quick

cantrip), the chance

of being caught depends

on the detectabil-

ity of the spoken component,

the material

components, and the necessary

gestures.

There are usually spellcasters

in the audi-

ence, and these people notice

subtle ges-

tures for what they really

are. As a side

note, it is difficult to

cast spells from the

stands without drawing the

attention of

nearby spectators. Also,

an unsuspecting

gladiator or soldier NPC

can “accidentally”

discover anyone hiding in

a corner with a

scroll.

Dungeon Masters can also

use “magic

police” to seek out illegal

spellcasters in

the games. An NPC cleric

or magic-user

can use the 1st-level spell

detect magic to

check the arena before each

duel; like-

wise, several spellcasters

can work as a

team to hunt down rule-breakers.

DMs

might even arm their “magic

police” with a

staff of the magi or a wand

of magic detec-

tion and back them up with

a dozen heav-

ily armed soldiers. The

strength of this

deterrent force should be

increased only

to match the stubbornness

and determina-

tion of spell-using PCs.

Punishment for

such crimes may be determined

by trial at

a later point; such actions

usually result in

a verdict of guilty, which

carries a punish-

ment as severe as the DM

wishes to make

it (execution is common).

In other in-

stances, the perpetrator

may be detained

(held magically) and offered

as a special

execution during the gladiatorial

games.

4. Psionics. The use of

psionics in the pit

is as strongly restricted

as the use of

magic. A psionic gladiator

can be detected

when his opponents continually

become

wild or zombielike. If a

gladiator‘s foes tell

tales of insanity, confusion,

sleep, rage,

and other effects that struck

only during

the duel, the authorities

may become

suspicious. A suspected

psionic is immedi-

ately banned from the arena,

and a proven

psionic faces the same punishment

as a

proven spellcaster.

It is easier to hide psionics

use than

magic use, but psionics

have their own

unique dangers. These dangers

are called

brain moles, cerebral parasites,

intellect

devourers, and thought eaters

(all from

the Monster Manual). DMs

should con-

sider their use against

PCs who cannot

otherwise be stopped from

the illegal use

of psionics.

5. Poison. Poison is a violation

that

draws the severest punishments

for the

same basic reasons as magic

use does. The

chance of detecting a poisoned

weapon is

noted in the Players Handbook

in the

assassin’s class description.

Since sheaths

are rarely used for weapons,

many people

coming within 10’of any

weapon notice

any poison. The rule-breaker’s

opponents

have a good chance of detecting

poison

and will shout for justice.

Poison use is too

dishonorable and risky for

any wise

gladiator to attempt.

6. Missile combat. Very

rarely should

missiles be used in the

arena (a PC re-

tiarius can throw the net

and trident if he

wants, but an NPC retiarius

holds both

weapons, swinging one end

of the net to

catch an arm or leg, and

stabbing with the

trident). One reason is

that the sport is

designed to display melee

fighting skills;

archery contests are another

game alto-

gether. Another reason is

that battles must

be confined to the arena,

negating the

chance of accidental injury

to the politi-

cians who sit close to the

pit. Also, a wise

emperor or warlord would

not want to

test the gladiators’ loyalty

by putting him-

self in spear or arrow range

of them.

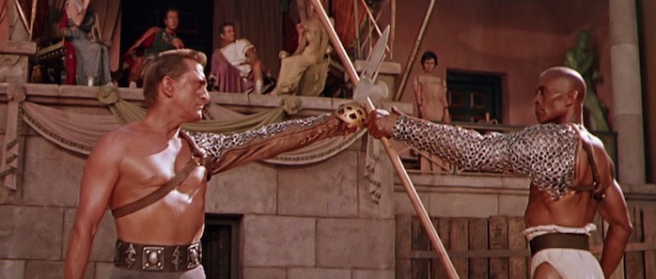

Many prisoner-gladiators

would enjoy the

chance to strike at a spectator,

a guard, or

the sponsor, all of whom

are out of sword

range from the arena (remember

the

trident-throwing gladiator

from the movie

Spartacus?).

The medieval arena

The main difference between

classical

and medieval games lies

in the equipment

which the gladiators use.

Armor is still

kept to a minimum, DMs can

provide the

fighters with any armor

and weapons

common to the AD&D game

(see Table 8

for suggested equipment).

For random

levels of opponents, roll

1d6 -2 (minimum

of 1) or 1d6 + 3 for opponents

of upper-

level characters.

Medieval guards often carry

longbows

when they patrol the amphitheaters.

Long

distance weapons put them

at a strong

advantage over the gladiators,

decreasing

the chances of rebellion.

The guards also

tend to avoid close contact

with prisoner-

gladiators so that the prisoners

have little

chance of acquiring missile

weapons.

The Oriental arena

Oriental gladiatorial games

need rules

that are not necessary in

classical games.

First, Table 2 cannot be

used because no

honorable Oriental character

asks for

mercy from a crowd of strangers

(such

behavior only draws the

crowds wrath

anyway).

Second, opponents gain or

lose honor

more intensely because of

the presence of

an audience. Double all

honor point adjust-

ments ( + or -) at the end

of each duel.

Third, special social problems

arise in

the organization of the

gladiators.

Whereas warriors mix freely

with crimi-

nals in classical games,

Oriental characters

are not so open minded.

What honorable

samurai would willingly

duel against a

murderer-peasant? Why would

a fighter

re-enter combat with a war

prisoner

whom he previously defeated

in battle?

Because of these social

problems, Orien-

tal games are divided into

two types:

1. Games of Honor. These

games are

held when someone offers

prizes to “the

best warriors in the land.”

If money is

offered to the winners,

award them four

ch’ien per level of the

losers. Other prizes

can include positions in

the military, weap-

ons of quality, marriage

to a maiden of

virtue (for suitable duellists

only, of

course), or anything else

the DM prefers.

Valuable offers attract

volunteers from

all over the country. The

bulk of this gladi-

atorial mass is made up

of bushi, kensai,

and ronin samurai. Regular

samurai are

restricted from the games

because lords

do not want their retainers

to die uselessly

in such contests; thus,

no permission to

compete in these events

will be granted.

The duels are conducted

in the same

general manner as in classical

games. They

are fought until death or

until one charac-

ter surrenders to the other.

Though no

armor is permitted, each

combatant is

allowed to wield his own

weapons. Thus,

most of the weapons used

are swords,

naginatas, and spears. For

the class level

of an NPC opponent, roll

1d6 + 3.

2. Games of Dishonor. These

games are

held when a lord stages

combat between

criminals (especially captured

bandits) or

when a victorious military

commander

stages combat between prisoners

of war.

The main purposes of such

games are

punishment and execution.

Combatants are typically

barbarians

(uncommon), bushi (common),

kensai (very

rare), monks (rare), disheartened

samurai

(very rare), and yakuza

(rare). When these

men are armed, the arena

is surrounded

by as many swordsmen and

archers as

possible to prevent violence

outside the

arena. Furthermore, the

sponsor of the

game is almost always an

upper-level

fighter, just in case a

gladiator dares to

challenge him to enter the

arena for a

duel.

Samurai-gladiators are almost

non-

existent in games of dishonor.

To capture

samurai warriors is very

difficult, since

most of them kill themselves

before being

taken prisoner. (As a side

note, a character

who wishes to commit hara-kiri

must roll

a 4d6 Wisdom Check, adding

his honor

score divided by ten. A

successful check

means automatic death, and

failure means

double damage taken from

the weapon. A

character can attempt this

check once per

round.) To force samurai

unwillingly into a

duel is nearly impossible,

since they have a

habit of ignoring their

chosen opponents

and attacking the guards

and sponsor of

the event. In this way,

samurai-gladiators

usually die in a hail of

arrows before

bowing to their captors’

wishes. Other

character classes might

also be rebellious,

but it is the samurai class

which reacts

with such predictable and

violent

stubbornness.

Gladiators of dishonorable

games are

treated poorly and often

ridiculed. Loss of

honor is a strong influence,

since each

gladiator has either been

accused of a

crime ( -4 points) or taken

prisoner ( - 10

points). In addition, to

fight in such a game

costs a criminal -2 honor

points per duel,

and costs a war prisoner

-1 honor points

per duel. These penalties

are given in

addition to the doubled

honor point adjust-

ments previously mentioned.

The gladiators wear no armor.

War

prisoners fight with the

weapons of the

battlefield, such as daggers,

swords, nagi-

natas, and spears, while

criminals fight

with more exotic weapons.

Consult Table 9

for the arming of Oriental

criminal-

gladiators. For class levels

of all dishonor-

able gladiators, roll 1d6

- 1.

All dishonorable duels are

fought to the

death, and all psychic duels

must lead to

actual combat, not a retreat

by the loser.

Oriental spectators accept

nothing less

than an all-out attempt

to win by both

combatants.

Winners of the games are

occasionally

set free. After a fight,

divide the victor’s

honor score by 10 and then

roll 3d10. If

the rolled number matches

the adjusted

honor score or less, then

the prisoner is

allowed to leave — without

weapons,

armor, money, or other possessions.

There

is no gaining of honor for

being set free.

Freed gladiators tend to

slip away quickly

and quietly, ashamed of

their previous

captivity.

Battle variations

The first priority of gladiatorial

games is

their ability to entertain

and excite an

audience. For this reason,

some interesting

variations are described

below.

1. Blind combat. In this

type of duel, the

combatants enter the arena

and face each

other at close range. Then

they put on

their helmets, which have

sealed visors

that cover their eyes. Each

opponent at-

tacks at -4 “to hit,” unless

he has blind-

fighting proficiency as

described in the

Dungeoneer’s Survival Guide.

NPC gladia-

tors each have a 1% chance

per level of

having this proficiency.

A blinded gladiator

cannot ask for mercy from

the audience,

since his opponent will

not see the plea

and thus continues to attack.

2. Mounted combat. Gladiators

occasion-

ally fight from the backs

of light war-

horses. Riding proficiency

is necessary for

all horsemen. Classical

fighters typically

carry small shields and

short swords, and

sometimes (30% chance per

match), all

horsemen in the duel wear

leather armor.

The most effective way for

a horseman

to fight other riders with

hand-to-hand

weapons is to circle around

his opponents,

striking whenever possible.

Every round,

each rider makes a riding

check to get

himself into position for

an attack. When

only two riders are fighting,

each check

receives a +5 bonus. A character

can

attempt this check only

once per round; if

successful, he can choose

whichever oppo-

nent he wants to attack.

Only two riders

can attack a single opponent

at one time,

and both attackers must

make their riding

checks as described.

If two characters make successful

checks and attack each other,

they roll for

initiative for that round;

in this instance,

both characters face each

others’ shield

sides.

When a horseman makes a

successful

riding check against one

who fails the

check, roll on Table 10

to determine which

side the attacker is facing.

Use 1d8 if the

defender has only one opponent;

1d10 if

the defender has two or

more opponents.

Table 10 gives the following

possible

targets:

Shield side. The defender

adds his shield

bonus (if any) to his armor

class.

Front. The defender adds

his shield

bonus (if any) to his AC,

and can return an

attack in that round at

-4 “to hit.”

Weapon side. The defender

receives no

shield bonus to his AC,

but can return an

attack in that round at

-2 “to hit.”

Rear. The attacker strikes

at +2 “to hit.”

The defender receives no

dexterity or

shield bonus to his AC.

If a mounted gladiator fights

against an

opponent on foot, use the

rules for

mounted combat in the DSG.

3. Blind mounted combat.

Chaos results

when mounted gladiators

are ordered to

wear helmets with blinding

visors. During

melee, each horseman rolls

a riding profi-

ciency to avoid slamming

his horse into

other horses. This check

is made at -4,

with an additional -2 per

participating

horseman after two. When

horses collide,

the riders must pass riding

checks or fall

to the ground, suffering

1-3 hp damage.

For combat, use the rules

for mounted

combat previously described,

except that

the checks made to position

the riders for

their attacks are made at

-5. Randomly

determine which rider each

character is

attacking. Blinded duellists

strike at -4 “to

hit.” In this form of combat,

blind combat

proficiencies also apply.

4. Bridge combat. A bridge

can be con-

structed in the arena on

which gladiators

can fight on (see the DSG

rules for fighting

on a bridge). Usually, there

is only enough

width for one size-M character

and

enough length for 20 size-M

characters.

DMs can widen the bridge

so that two

combatants can stand side

by side, or

shrink it so that a gladiator

must make a

Dexterity Check each round

to keep from

falling.

One of two landing spots

is typically set

up beneath the bridge. The

first is a pit of

red-hot coals and burning

wood, which

immediately kills anyone

who falls into it.

The second is a bed of spikes.

Unfortunate

characters fall onto 1-6

razor-sharp blades,

each causing 1d8 hp damage.

Because of

the deadliness of bridge

combat, only

expendable lower-level gladiators

are sent

into such duels.

5. Mass battles. Small giadiatorial

armies

can fight in the arena.

The DM needs the

BATTLESYSTEM™ Fantasy Combat

Supple-

ment to stage these tiny

wars.

Classical games usually

involve a large

group of lightly armed gladiators

and a

small group of heavily armed

gladiators —

for example, 20 samnites

fighting 40

retiarii.

The battle lasts until one

side is elimi-

nated, unless units are

sent in to replace

those which are lost. There

is no random

way to determine such things

as the num-

ber of participants, the

strength of each

unit, or if replacements

are used. These

decisions are left to the

DM.

Mob units are used for untrained

gladia-

tors and zero-level criminals.

These units

have no commander, since

they have sim-

ply been given weapons and

then pushed

into the arena. Being unwilling

fighters,

they have an Initial Morale

rating of 8.

Regular units are used for

trained gladia-

tors. Since these warriors

are individual-

ists and not group fighters,

they have an

Initial Discipline rating

of 4. For the same

reason, a Brigade Commander

is rarely

seen in the pit. More likely,

Unit Com-

manders lead the giadiatorial

groups.

Several Unit Commanders

can be allies on

the same side, but they

move and fight

without relation to each

other. Also, no

morale checks or fighting

withdrawals are

allowed to regular units,

since all partici-

pants fight to the death.

Cavalry and chariot units

can be used

sparingly in the 200’-diameter

pit. How-

ever, fire attacks are rarely

used because

smoke blocks the spectators’

views and

chokes many of them. Artillery

is also

prohibited, since a rebellious

crew might

decide to launch a flaming

boulder into

the audience or at the sponsor’s

platform.

Table 11 in the BATTLESYSTEM

rule

booklet gives a possibility

that a PC or NPC

body becomes “lost.” Ignore

this ruling in

the arena. All dead characters

lay “on the

field” for recovery.

6. Sea battles. Gladiatorial

naval combat

was occasionally seen in

Ancient Rome.

These battles were sometimes

held on a

pond or lake, but the rules

given here are

to be used when the arena

itself is flooded

with water. Game sponsors

find it less

expensive to use small ships

than to buy

war galleys that are rammed,

burned, and

possibly sunk.

The arena is filled with

water that is

chest-deep to size-M characters.

This

depth allows the use of

raft-ships, and also

prevents the meaningless

(and, for the

audience, boring) drowning

of gladiators.

Merciless DMs can place

sharks (or

worse!) into the water to

keep the fighters

on their toes. In such a

case, each charac-

ter in the water has a 20%

chance per

round of being attacked

by a creature in

the water.

Small, oared ships are manned

by teams

of 10 gladiators, often

all in the same

fighting style, and led

by the man with the

highest class level. Roll

on Table 1, 8, or 9

to randomly determine a

team’s style. The

boats have 2-5 hull points

each, are 15-20’

long, 6-8’ wide, and travel

at rowboat

speed. In each battle, 1d6

+ 6 boat teams

participate, and the battle

lasts until gladi-

ators from only one team

are able to

continue.

BATTLESYSTEM rules are useful

to

resolve combat. A unit (or

boat team) is

made up of a single counter.

There are no

Heroes unless a PC is the

only survivor of

the team, since a gladiator

who willingly

sets out on his own is considered

a traitor

and is treated like an enemy

by his own

team. If a PC or important

NPC is in a unit

that gets eliminated, consult

Table 11 for

(continued on page 18)