The Black Leopard Cult

Chapter 15: DAILY LIFE IN KARA-TUR

The Black Leopard Cult

| Dress | Food | Buildings | Law & Justice | Manners |

| Names | - | - | - | Oriental Adventures |

The world of Kara-Tur and the real lands

that provide its inspiration are not necessarily those familiar to

most DMs and players. There are many differences in dress, food, customs,

and behavior-differences that are

small in themselves, but when added together make a culture and style

of life foreign to most players. This

section of OA describes some of these differences,

aiding the DM and players in capturing the

feel and color of the world. DMs especially should note that this section

does not and cannot describe all of the

variety and richness of a land so different from those of the west.

It is strongly suggested that further reading be

done. The bibliography at the back of this book lists many titles that

give more information and detail. The DM

is strongly encouraged to read one or more of these titles.

The customs and ways of life described in this section are not absolutes.

Just because it is stated here

does not mean this is the only choice. The Orient covers a vast number

of different types of cultures, even more

so when the different time periods are considered. What may be true

in one part of the Orient may be entirely

different in another part. Also, since this is a fantasy world, the

DM should freely change or alter aspects of the

world as he wishes.

For convenience, this section is divided into general sections dealing

with different parts of daily life.

Covered here are dress, food, buildings, religion, justice, manners,

and names. Each section describes some (but

not all) of the tastes, customs, and habits particular to the Orient.

In Kara-Tur, as in nearly all lands, men

and women wear clothing. For the most part this is a matter of

practicality, a necessary device to keep warm and dry. Clothing also

provides a second and almost as important

service-identifying the rank or status of the wearer. Nearly all clothing

is decorated in dyed patterns or

embroidery, but the type of clothing, the quality of the decoration,

and the materials used all indicate status.

The most common materials used in making clothing are cotton and silk.

However, other materials are

also used, generally confined to a specific region and to the lower

classes. These materials include pounded tree

bark, flax, wool, woven horse-hair, furs, paper, and hemp. Heavy leathers

would be used for durability, while

soft leathers like deerskin would be used for items requiring flexibility

or lavish decoration. Primitive tribesmen

and poor commoners would use the cheapest and most available materials

for their clothing. White is typically

the color of mourning, so nearly all cloth is dyed. Common colors are

browns, ochres, yellows, grays, and

blues. The brighter colors of green, pinks, and reds are rarer and

are commonly worn by those of higher station.

Dyes are made from flowers, nuts, barks, woods, and certain minerals.

The main articles of clothing vary from land to land and climate to

climate. Most common is a set of

short trousers, normally made of cotton. These wrap around the waist

and tie with strings. They can be left loose

at the bottom or tied to fit snugly around the leg. They are normally

loose fitting so that they can be pulled up

for wading through rice paddies or streams. They are often dyed in

stripes or other patterns. Such pants are

typically worn by peasants of both sexes. Commoners normally wear a

short robe over the trousers, tied with a

belt. Wealthier and more important persons often omit the trousers,

wearing one or more long robes instead.

Among the nobility, wearing layers of robes is standard. Each layer

is of a different color and peeks through at

the ends of the sleeves and around the collar. Arranging the color

and order of the layers is an art for many of

the ladies of a noble's court. Robes have wide, open sleeves, both

for artistic and practical effect. In cold

weather, the sleeves serve as muffs, since gloves are not normally

worn. They are also used as pockets where a

handkerchief or string of cash can be kept safely tucked away. Robes

are often lavishly decorated with dyes,

brocade, and embroidery and may be quite valuable. During colder seasons,

warmth is achieved by adding more

and heavier layers of robes. An outer coat of quilted cotton is worn

to protect from cold winds. As the day

grows warmer, layers are removed to maintain comfort. In rain, peasants

wear a simple rain cloak made from

layers of straw (mino).

The choice of footwear also depends on the land and the climate. The

simplest and most common is a

sandal of woven straw. These are cheap, durable, and easy to make.

Sandals made of woven straw or wooden

blocks are worn throughout Kozakura. In Shou Lung and T'u Lung, slippers

of soft leather or cloth are worn by

refined people while soldiers normally wear a short soft-leather boot.

Sandals are worn by the common people,

who cannot afford to ruin good shoes in muddy fields. In the cold north

lands, the common shoe is a leather

boot wrapped in fur leggings to protect from snow and ice.

Hats are a clear sign of a person's status. Nearly

everyone has or wears a hat. Peasant hats are

practical-round and broad-rimmed of woven straw or bamboo. These keep

the sun off the field hand and double

as baskets when needed. Wandering shukenja and monks may wear hats

like these or ones that are baskets that

cover the entire head. Hats of nobles are often small, the style indicating

the position of the wearer. Huge

rimmed hats of horsehair are worn by gentlemen in some parts of Kara-Tur.

A simple scarf or piece of cloth can

be used to provide protection from the rain.

Personal beauty is different in Kara-Tur, too.

Men, especially those of rank, pride themselves on their

grace and beauty. A pale complexion is considered best and some men

have even been known to pluck their

eyebrows. It is common to use perfumes and fragrances and those of

worth are often quite skilled at mixing

these. However, the majority of men fall short of this ideal, being

hardened by the weather and the accidents of

life. For women, personal beauty is also quite different. It is standard

practice for a woman to blacken her teeth.

Indeed a pearly white smile is considered

an unfortunate flaw, not the attractive feature of the west. In addition,

women pluck their eyebrows and then repaint them in a delicate thin

line. Again a pale complexion is most

attractive and many women powder their faces to give the best and palest

color possible.

Rice is the one constant throughout the civilized

lands of Kara-Tur. Everyone eats rice and rice,

in one

form or another, is served with virtually every meal. In Shou Lung

and T'u Lung, people do not greet each other

with the friendly "Hello" of the west, instead saying, "Have you eaten

rice today?" The intention is the same,

but the importance of rice in daily life is clear. Rice is used in

a multitude of ways. It is boiled and served as a

main course. It is cooked into a paste-like gruel. Leftover rice is

mixed with meats and vegetables. It is

vinegared, shaped, and served cold. It is pounded and crushed and made

into rice-cakes. It is ground into flour

and formed into buns or noodles. It is mashed, fermented, and made

into sake, a strong drink. Like wheat in the

west, rice is the stuff of life in Kara-Tur.

When rice is not available or too valuable to serve at the common table,

yellow

millet,

sorghum,

or

barley is often substituted. This is the poor man's food. These are

normally pounded into cakes or cooked into a

thick gruel. Beans of various sizes, shapes, and colors are also used

in addition to or in place of rice. Soybeans,

red beans, black beans, and brown beans may all be stewed or mashed

into a paste. This paste may be

fermented, flavored, dried, or sweetened. It is used as a dip, stuffed

into buns, formed into candies, or used as a

sauce. From soybeans comes the unusual prepared foods soy sauce and

tofu. Tofu is prepared from the juice or

"milk" of mashed soybeans. This is curdled and pressed into semi-soft

cakes. It may be stewed, dried,

deep-fried, or prepared in a variety of other ways. Soy sauce is prepared

through a complicated process of

mashing, fermenting, soaking, and rinsing. The end result is a thin,

salty sauce used as a flavoring for nearly

anything.

Next to rice in importance come vegetables of many different types and

flavors. These, grown in family

garden plots, are stewed, fried, pickled, and steamed. They are almost

never eaten raw, except as garnishes.

Along with the huge variety of vegetables are an assortment of fruits,

nuts, grasses, and flowers. Plant products

that are eaten include the shoots of bamboo plants, the roots of water

chestnuts, melons, giant radishes,

mushrooms in great variety, bean sprouts, pumpkins, squash, chestnuts,

potatoes, cucumbers, turnips, cabbage,

onions, leeks, peaches, pears, persimmons, sweet potatoes, carrots,

walnuts, almonds, lychees, lotus root, plums,

cherries, bananas, peanuts, and many, many others. -Some of the more

unusual preparations include pickled

greens or radishes (often with chilies), pickled plums (indeed virtually

anything will be pickled), dried flower

buds, dried chestnuts, and pastes.

Also important to the Oriental diet are the products of the water. Obviously,

only those living near the

sea, a river, or lake consume these things. Hundreds of varieties of

fish are eaten, taken fresh from the water,

ranging from the commonplace to the exotic. A few of the desired delicacies

include pufferfish (which is deadly

poisonous if incorrectly prepared), sea cucumber, jellyfish, octopus,

eels, shrimp, and fish maw. Various types

of kelp are harvested from the ocean to be dried and used in soups

and as flavorings. Virtually anything that

comes from the sea is used in some way.

Fish is the main source of meat; however, other meats are eaten too.

Chicken and pork are most

common. These are prepared in a variety of ways. Game is also eaten

when available. Beef is seldom eaten as

cattle are very rare and are specially regarded. Barbarians are known

to eat mutton and horsemeat, especially at

feasts.

Tea is clearly the most common drink. It comes in

many different varieties. The majority of people drink

it plain. Among the nomads, however, it is mixed with milk and sugar

and even served as a soup. In addition to

tea, rice wines (sake and the like) are also drunk. These are served

heated in small cups. Beers are also made

and drunk with meals. The people of the steppes make a drink of fermented

mare's milk, which they claim is a

refreshing tonic. On special occasions this is mixed with mare's blood,

especially for warriors before or after a

battle. While the steppes warriors drink and use a great deal of milk,

it is rare elsewhere.

A typical day's meals for a group of adventurers might be something

like this: In a town, the morning

meal might be steamed buns, dumplings, rice or rice gruel, and several

types of pickles. The mid-day meal is

likely to be the largest with rice, vegetables, maybe fish or chicken,

more pickles, and tea. Late in the day, the

characters may indulge in some tea and rice candies or sweet buns.

Finally, in the evening, a light meal is

served of rice and a few simple delicacies. When traveling, the meals

will be somewhat different. The morning

meal, before breaking camp, may be rice gruel, plain boiled rice, millet,

or barley. At midway, there may or

may not be time for a meal. If there is a meal, it is likely to be

ricecake, cold rice, or a packet of rice, fish, nuts,

and dried seaweed or pickles wrapped and tied in banana leaves. If

available, fruit will round out the lunch. In

the evening dinner will be more rice and dried fish and vegetables,

fresh or dried. If the day's hunting has gone

well, fresh game may be eaten instead of fish.

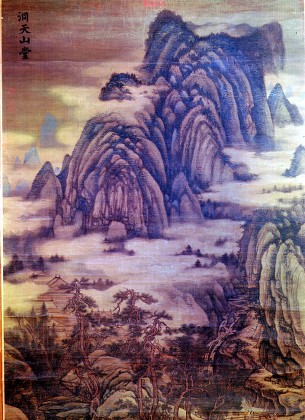

There are three main building types in Kara-Tur--the

homes of commoners, the palaces of the wealthy

and powerful, and temples. Each has distinctive methods and materials

used in building. Several floorplans are

provided in this section for the DM to use in designing his adventures

and to provide him with some idea of the

typical arrangement of buildings.

The peasant homes are customarily built of wood or clay brick. In its

simplest form, the wood house is a

single large room with a bare-earth floor and an open framework of

ratters overhead. The roof is made of a

thick layer of thatch and is steeply angled to shed snow and water.

The roof has broad eaves that extend well

over the sides of the house, shading from the hot summer sun and winter

snow. Several windows are built into

the walls for light, covered with a simple wood lattice, removable

shutters, bamboo shades, or glazed paper.

Surrounding the outer walls of the house is a small veranda-a raised

deck as wide as the eaves and often covered

with woven straw mats. Inside the house, the central room is dominated

by an earthen hearth, normally a

stone-lined pit dug into the floor. Above this is a hook used for hanging

cooking pots when preparing meals,

especially rice. The smoke from the fire escapes through a smoke hole

in the roof. Since there is no type of

central heating or fireplaces for warmth, much of the family life centers

around this hearth, especially in winter.

Not all houses consist of a single room. Sometimes the house is divided

into separate sections by raised

platforms. The central area of the house is still the earth-floored

hearth area, but adjoining it are raised wooden

platforms. These are used for sleeping and other activities. They are

separated from the main room by

removable screens of paper or permanent wooden walls. Storage spaces

are built into the walls and under the

platforms. Sometimes an attic is built and used as a storage area and

sleeping space for the younger family

members. The attic is reached by a broad-stepped ladder.

The thatched roof of such a house requires regular care and repair.

In wealthier homes this thatch is

replaced by layers of glazed tile. Although more expensive, these have

the advantage of durability and have

quickly become a sign of the status of the homeowner. In addition,

the ridge of the roof and the edges of the

eaves are often decorated with wooden forms and carvings.

In the cities and large towns, such houses would be built tightly packed

together on narrow twisting

streets. Since thatch is not readily available, most of the houses

are tile-roofed and a thatched roof is the sign of

a truly poor man. Most of the shops and businesses are in the same

building as the family home. During the day,

large front shutters are opened to form a table for holding goods offered

for sale. Behind the row of houses may

be a common courtyard with a well for use by all the families in that

block. Larger and wealthier homes are set

off from the street by walled gardens or form a square around a central

courtyard. Houses are seldom more than

one story high.

In addition to the main building providing the family living quarters,

there may be other buildings

owned by the family-workshops, stables, and granaries. Most of these

are built in a similar style to the main

house. Granaries, however, are almost always built of plaster and stone.

This is due to the great risk of fire.

While the family home can be rebuilt, should the granary burn down,

the loss of wealth in the form of rice could

never be replaced.

Obviously, buildings making such great use of wood, thatch, and paper

are very susceptible to fire.

Building fires are greatly feared, especially in large cities. In such

densely packed areas, winds quickly carry

sparks from a blaze to nearby buildings, touching off devastating fires

that sweep through entire sections of the

city. Every ward of the city has organized teams of fire-fighters (normally

under the control of a noble).

Practices are primitive, consisting of bucket gangs and pulling down

nearby buildings to haft the spread of the

blaze.

The other type of peasant home is made from pressed clay brick. This

is commonly used in areas where

good building wood is scarce. Such buildings are normally two stories

tall. They are often built around a central

courtyard or have a walled garden attached. The cooking is done in

a kitchen area which is dominated by a clay

or brick stove. Like other houses, there is no central heating or fireplaces

for warmth. Charcoal braziers are

placed in rooms when the weather is cold. The roofs are often flat,

used as decks, or slightly canted and covered

with glazed tile. Windows are built into nearly all the rooms and are

covered with wooden lattices or heavy,

removable shutters. The houses are often decorated with red-painted

ornaments (red being considered a lucky

color). Such houses, being mostly plaster, clay and stone, are far

less susceptible to fire.

The houses of nobles and the wealthy are in many ways identical to their

peasant counterparts, except

larger and more lavish. Nearly all include extensive garden grounds

and large numbers of rooms. These are

necessary to maintain the proper image of wealth and status and to

house the retainers, servants, and wives of

the lord. The garden grounds are carefully landscaped and often include

a man-made pond or stream. Such

homes are always surrounded by walls. These ensure privacy and, from

a more practical side, protection from

wars and revolts. All have solid wooden floors and chambers divided

by movable screens.

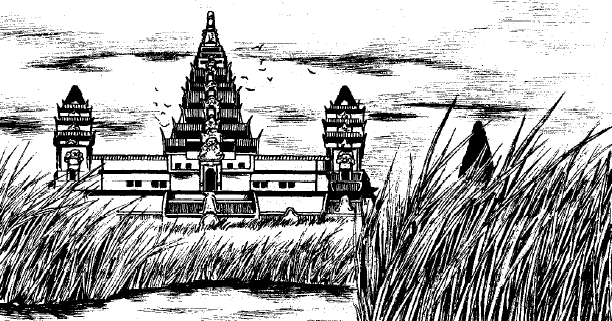

Temple buildings are quite lavish in their construction. Generally,

a group of buildings are organized

within a single walled compound. The most common building material

is wood, although magnificent towers

(pagodas) are often built of stone. The temple usually rests on a raised

foundation and is surrounded by terraces

of stone. Around the outside of the building, under the broad-tiled

eaves, is a broad veranda. The inside has a

large main hall dominated by a statue or artifacts of the deity, quite

imposing in size. Attached to the main hall

are several smaller chambers for the use of the priests of the temple.

The grounds of the compound are normally

landscaped and planted with different types of flowering and decorative

trees.

In addition to the main types of architecture, there is the special

class of military buildings-castles,

watchtowers, and the like. Although the styles of architecture are

different, these castles have many similarities

to those of the west. The castle is usually located on the most commanding

or strategic point of ground. The

compound centers around the main building many stories tall-the equivalent

of the donjon or keep of the

western world. Like the keep, this building forms the last point of

defense. The foundation is made of heavy

blocks of stone rising higher than a man. The entrance to this tower

is reached by a series of ramps and

staircases. Attached to and surrounding this tower are a series of

lesser towers and walls. These have only a few

gates that lead to narrow winding avenues. The walls are pierced with

loopholes and openings, allowing the

defenders to fire upon the attackers as they advance. Surrounding the

castle is a series of ditches or moats,

smaller walls, and more towers. Sieging a castle is a formidable undertaking!

The average man of Kara-Tur does not attend

a church or temple on a regular basis, indeed the concept

of a church as a separate entity clearly identified from all others

is somewhat strange to him. For him, religion

organized on such a scale does not exist. However, this does not mean

the average man is not pious and

respectful of religion, nor that the temples and monasteries are in

total anarchy. It is just that the attitude toward

religion is vastly different.

There are several different religions in Kara-Tur, each with its own

set of beliefs and practices-The Way,

The Path of Enlightenment, The Eight Million Gods, ancestor worship,

the cult of the state, and more. Each is

distinct, teaching enlightenment, perfection, and salvation according

to its own methods. Each believes it is the

correct path. However, in practice, few common people follow the beliefs

of strictly one religion. Instead, they

take no chances, not wishing to offend one deity or another. As a result,

commoners make offerings, listen to

sermons, celebrate holy days, and pray at temples of many different

religions. Nor is this considered unusual or

incorrect.

The various religions, when compared to those of the west, are extremely

tolerant of one another.

Several religions will be practiced in the same area, their temples

often side by side. It is not unknown for a sect

to adopt some of the practices or outward forms of another religion.

These adoptions are re-explained according

to the beliefs of the religion. Thus minor gods may be adopted and

identified as different forms of a deity

already worshiped by the religion. The clergy are faithful to their

particular religion, not practicing any other.

Although they would like the peasants to follow only their teachings

and strive for this, they know that the

common folk follow many different beliefs at once.

In addition, religions are often divided into sects. The various sects

of a religion all have the same

overall goal and beliefs, but disagree as to what is the best method

to pursue these beliefs. Some may hold to

chanting a phrase over and over again, another thinking a different

phrase is required, and a third foregoing

chanting for breathing and physical exercises. Each believes its methods

are the correct way. Often fierce

rivalries develop between different sects, leading to feuds and violent

clashes. Indeed, sects of the same religion

are often more hostile to each other than they are to entirely different

religions!

Most of the lands of Kara-Tur are quite civilized

and organized. Law and order is an important part of

this civilizing influence and a great deal of effort is devoted to

maintaining order and harmony throughout the

lands of Kara-Tur. Therefore, regular systems

of laws, courts and punishments exist. Although the exact laws

and punishments may vary from country to country, the machinery of

justice is remarkably the same throughout

Kara-Tur.

The center of the legal system is the law court. These courts are found

throughout the land, generally

one to every province and major city. The head of the court is the

magistrate, who has broad powers. He may be

a scholar who earned his post by passing the examinations, a noble

appointed to the position by the emperor, the

daimyo of the province, a learned sage, or the village headman. His

official assistants are the bailiff and the

constables. These in turn may hire outcasts as assistants. In addition,

the magistrate may have one or more

secretaries to assist in his work.

When a case first comes to the attention of the court, it is the responsibility

of the bailiff and constables

to gather the evidence required. Physical evidence is brought to the

court and held until the trial. Witnesses and

those involved in the case can be arrested and held by the constables

or ordered to appear at the time of the trial.

There is no protection from arrest, save the possible displeasure of

the magistrate or higher authorities.

Obviously, this can make it very difficult to arrest important or powerful

people. Once all the evidence and

witnesses have been gathered, the trial date is set, usually with little

delay.

At the trial, the accused and the accuser are each allowed to state

their case. There are no lawyers and

the magistrate asks all necessary questions. If the accused or the

accuser is reluctant to speak, the magistrate can

order the person beaten or tortured to aid their memory. Similar punishments

await them if they are out of order.

Witnesses are also brought in front of the magistrate for questioning

and the magistrate can order force used to

extract their testimony. The bailiff oversees the courtroom, maintaining

order, producing the witnesses, and

administering beatings as necessary.

If the case involves murder, a spellcaster may be summoned to use his

spells to speak with the dead

person. Such testimony is accepted as fact. Spells may also be used

to determine the truth of statements from

the various testifiers. After all evidence has been heard and examined,

the judge arrives at a decision. In this his

secretaries aid him, stating the existing laws and previous cases.

Persons of higher rank, because their responsibilities are greater,

often receive special considerations.

Actions which are crimes for the commoner are often not if committed

by one of a warrior class. Thus, in lands

such as Kozakura, a samurai has the right to cut down a commoner he

deems to be insulting or truculent without

being charged with murder. Likewise, if he receives the proper approvals,

he can undertake a vendetta to avenge

the death of a family member. On the other hand, these same classes

are often punished more severely for

actions which are not as criminal for the commoner. Gambling and drunkenness

are much more severe crimes

for the samurai than for the common people. In these cases, their crime

is greater by having broken their trust.

Punishments are fixed by law, but the magistrate has some power to

interpret the law and alter the fixed

punishment to one of lesser or greater severity. For commoners, typical

punishments include execution,

branding, loss of the hands, payment of fines, imprisonment, banishment,

slavery, the wearing of a heavy yoke,

and public announcements of their crimes. For those of the higher classes

the punishments include house arrest,

banishment, loss of position, and honorable death. For particularly

vile crimes (such as treason), the samurai

may be forced to undergo public humiliation in the form of execution.

The magistrate hears both civil and criminal cases. However, given the

harsh treatment of even the

innocent by the courts, most people attempt to settle civil complaints

without resorting to the courts. This is

often done by having a mediator arrange a settlement between the two

parties. This mediator, a priest or village

headman, decides the appropriate terms of the settlement. However,

t is up to both parties to agree to this.

Should this fail, the case may well come before the court.

To discourage crone and treachery, many of the governments of Kara-Tur

practice a policy of collective

responsibility. Collective responsibility holds the entire family,

village, or group responsible for the actions of

the criminal, not just the criminal himself. Thus, if a samurai is

banished for a crime, his entire family may be

banished with him. If a murderer hides in a village, the entire village

may be punished for the crime, not just the

murderer. Given such severe penalties, people, especially commoners,

are loathe to give aid or comfort to a

criminal, lest they be held responsible for his actions. While this

policy may seem unduly harsh, it has proven to

be an effective way of dealing with crime.

Finally, there is the practice of the vendetta, an act officially sanctioned

in some lands (such as

Kozakura). The vendetta is a required part of the samurai's honor.

When a family relation is murdered or slain

in a duel, it is the responsibility of the surviving family members

to track down and kill the perpetrator of the

crime.

Special rules govern the vendetta. Those engaging in a vendetta cannot

be of higher rank than the person

slain. Thus, the eldest son of a samurai family cannot undertake a

vendetta to avenge a younger brother (since

the eldest son is of higher rank). Likewise the direct retainer of

a daimyo cannot legally avenge the death of a

lesser retainer. Next, the avenger must be released from the service

of his lord. This is done by applying to the

lord, requesting permission to undertake the vendetta. If the lord

deems the cause to be just and does not require

the services of the samurai at that time, he releases the samurai from

service. When the vendetta is over, the

samurai can reenter the service of his lord with no penalties (indeed

he may have gained renown and approval

for his honorable actions). Finally, upon locating his man, the avenger

must receive the approval of the local

government to engage in the vendetta. Normally this is given with little

question. However, if the person hunted

is valuable to or a friend of the local lord, this permission may be

denied. Should the avenger act without

approval, he can be arrested for murder. However, if all the approvals

are given, the avenger can challenge the

hunted to a duel to the death at any time. Since everything is legally

done, the winner of the duel is not charged

with murder. Either side can have any number of seconds to assist him

in the duel-it need not be a one-on-one

fight.

The people of Kara-Tur, it is noticed by

gajin, are extraordinarily polite as a rule. They often go to

meticulous pains to behave in the correct manner. Indeed, among the

higher classes, incorrect or poor manners

is virtually as great a crime as murder and severe punishments can

be levied upon those who knowingly or

unknowingly commit some social faux pas. Correct manners mark clearly

the differences between various

social classes and, perhaps more importantly, help prevent the possibility

of embarrassing oneself in public.

This latter is of great importance, since there is perhaps no greater

sin than to be laughed at by others.

The bow is the most obvious expression of manners. It is not just a

way of saying "Hello:" It measures

the respect one has for the person bowed to. Those of lower status

bow lower to their superiors than their

superiors do to them. Indeed, a high ranking official may barely nod

to those under him. The greatest deference

one can make is to kowtow-kneel and touch one's head to the floor.

This is normally done only in the presence

of emperors and extremely powerful lords, but is sometimes necessary

when apologizing to or begging

forgiveness from another. Except in the presence of a powerful lord,

kowtowing is an extreme act, since it

represents the debasement and surrender of the person to another.

Manners also extend to what one says to another person. Statements,

even when spoken in jest, can be

insulting and offensive. Comments about another person's honor, courage,

dislikes, fears, family, dress,

behavior, friends, and even his possessions can be cause for insult.

Insults are seldom taken lightly. Truly

generous people might be able to ignore one or two spoken in jest,

but even they would surely not be able to

abide more. Therefore, to prevent these insults, conversations are

often stilted or phrased in extremely polite

terms to avoid offence.

It is the great concern over insults to honor and the risk of public

ridicule that prompts so much of the

politeness. Thus, the DM is allowed to cause player characters to lose

honor when they do things that would

bring them ridicule or make them look foolish. Player characters cannot

be cavalier in their attitude, they must

be careful of all they do and say.

In the western world, once a man is given a name, it stays with him

for the rest of his life. He may

acquire nicknames and aliases, but he can always be identified by his

given name. Indeed, the process of

changing a name could be a complicated legal matter, since it implies

a change of family and identity. However,

in the Oriental world, the situation is much different. Throughout

the life of an Oriental character, he can expect

to use at least two different names, quite often more. Each name would

be valid for the person, depending on

his age and situation. To further add to the confusion, aliases would

also be used when the person wished to

keep his identity secret.

The different types of names and their uses are listed below. Players

need not have names for all these

instances and many names are dropped (such as a childhood name) when

a new name is given.

A secret name given at birth which is never revealed, but is supposedly

known only to the gods.

Superstition holds that learning the secret name of a person gives

magical power over that person.

A childhood name given the person at birth that is used in daily life.

Childhood names are distinctly

different from adult names making it easy to tell if a person has come

of age.

An adult name given at coming of age that shows the person is now considered

a full adult with all the

inherent rights and responsibilities. Once the adult name is given,

the childhood name is seldom, if ever, used.

A hereditary family name used in conjunction with the person's personal

name. These are by no means

universal, generally reserved for the upper classes and nobles. For

the lower classes to attach a family name to

the personal name is considered insulting and above their station.

A clan or tribe name used to identity the person by the group he belongs

to. These are used by barbarian

groups where tribal affiliation is extremely important.

A place name that acts in many ways like a hereditary family name. These

are common among the

common people and identify the village, district, province, or etc.

the person is from.

A nickname used for much the same reasons as in the west-to tell two

people with the same name apart,

as an honor, or to ridicule them.

A substitute name for people of quality, craftsmen, or those working

at unseemly or improper

occupations. This is the closest name to an alias. However, it does

not disguise the identity of the person (everyone

knows who he is and what his station is). It only protects the true

name of the person from connection with

the undesired activity.

A substitute name chosen by an artist (writer, craftsman, etc.) either

because it would be improper to use

one's real name since it might have associations to some powerful person

or family, or to create a poetic allusion

about the artist (a poet choosing a name that is derived from that

of a great poet of the past).

A substitute name chosen by an artist, craftsman or warrior that shows

his connection to some school or

master.

A religious name taken upon entering the ranks of the priesthood. This

name shows the person has

severed his ties with his past life and become a new person. Religious

names normally have some special

significance in the religion.

Event names, chosen by the person or given by another, to tell of that

person's deeds and exploits. Such

names can come and go, depending on the whims and deeds of the person.

A posthumous name, given shortly after burial, to protect and assist

the departed person from evil

influences.