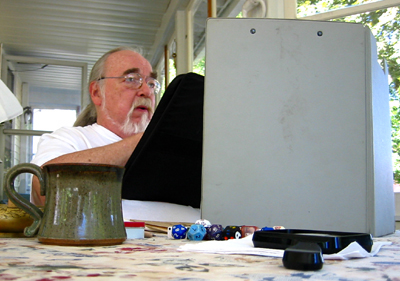

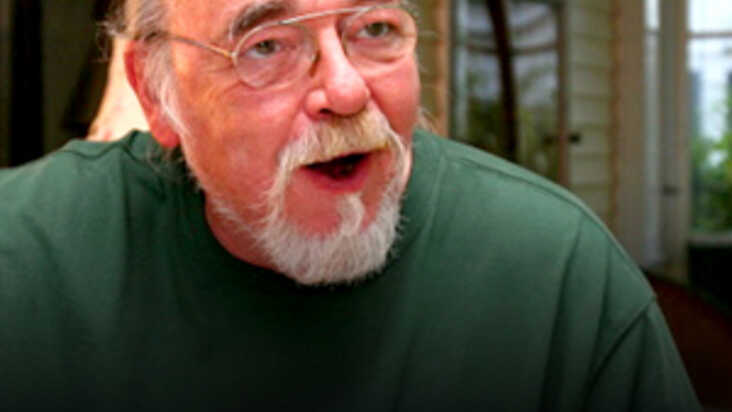

by Gary Gygax

by Gary Gygax

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon 31 | Best of Dragon Vol. II | - | - | Dragon |

Heroic fantasy adventure novels relate a story for the reader’s

leisure enjoyment. Heroic fantasy adventure games provide a vehicle

for the user’s creation and development of epic tales through the

medium of play. This simple difference is too often overlooked.

In the former case, the reader passively relates to what the author

has written, hopefully identifying with one or the other of the novel’s

leading characters, thus becoming immersed in the work and accepting

it as real for the time.

Games, however, involve participants actively; and in the instance

of fantasy adventure games, the player must create and develop a

game persona which becomes the sole vehicle through which the

individual can relate to the work.

Again, in the novel, the entire advantage related is a matter of fact

which the reader will discover by perusal of the story from beginning

to

conclusion, without benefit of input. In contrast, the adventure game

has only a vaguely fixed starting point; and the participant must,

in

effect, have a hand in authoring an unknown number of chapters in an

epic work of heroic fantasy.

A novel has an entirely different goal than does a game, although

both are forms of entertainment. The novel carries the reader from

start

to finish, while the game must be carried by the players.

An heroic fantasy adventure story should be so complete as to offer

little within its content for reader creativity, or else it is an unfinished

tale. This is not to say that the reader can not become involved in

the

telling, that there is no rapport between writer and reader, or even

that

the whole milieu produced by the work isn’t vividly alive in the reader’s

mind. It simply is to point out that the author has conceived a fantasy,

placed it in black and white before the reader, and invited him or

her to

share it.

A fantasy adventure game should offer little else but the possibility

of imaginative input from the participant, for the aim of any game

is to

involve the participants in active play, while heroic fantasy adventure

dictates imagination, creativity, and more.

The obvious corollary to this—and one evidently missed by many

players, designers, and even publishers—is that a truly excellent novel

provides an inversely proportionate amount of good material for a

game. The greater the detail and believability of the fantasy, the less

room for creativity, speculation, or even alteration.

Consider J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Ring Trilogy” for a moment. This is

certainly a masterwork in heroic fantasy—with emphasis on fantasy.

Its

detail is vast. Readers readily identify with the protagonists, whether

hobbit, human, or elf. Despite the fact that the whole tale seems to

vouch for the reliability of the plain and simple “little guy” in doing

a

dirty job right, in spite of the fact that these books could very well

deal

allegorically with the struggle of the Allies versus the Axis in WWII,

in

spite of the fact that the looming menace of the Tyrannical Evil simply

blows away into nothing in the end, millions of readers find it the

epitome of the perfect heroic fantasy adventure.

There are no divine powers to intervene on behalf of a humanity

faced by ineffable evil. The demi-god being, Tom Bombadil, is written

out of the tale because his intervention would have obviated the need

for the bulk of the remaining work. The wizards are basically mysterious

and rather impotent figures who offer cryptic advice, occasionally

do

something useful, but by and large are offstage doing “important

business” or “wicked plotting.”

Thus, the backbone of the whole is the struggles of a handful of

hobbits, elves, humans, and dwarves against a backdrop of human

armies and hordes of evil orcs. Irrespective of its merits as a literary

classic (and there is no denying that it is a beautifully written tale),

the

“Ring Trilogy” is quite unsatisfactory as a setting for a fantasy adventure

game.

If the basis for such a game is drawn straight from the three novels,

then there is no real game at all—merely an endless repetition, with

a

few possible variations, of the “Fellowship” defeating Sauron et al.

As

soon as the potential for evil to triumph is postulated by the game,

several problems arise: First, most dedicated readers, identifying

with

the heroic elements of the work, do not desire to play the despised

forces of Saruman or Sauron. The greater chance to win that evil has,

the greater the overall antipathy for playing the game at all. Tolkien

purists will also object to a distortion of the story.

Finally, even if the whole is carefully balanced, the best one can

come up with is a series of variations on the “Ring Trilogy,” whether

the reenactment is a role-playing game or a boardgame. The roles are

cast by Tolkien, the world is structured according to his wants and

desires. The more game put into this framework, the less of J.R.R.T.

the

participant will discover.

In similar fashion, imagine a game based on the exploits of Arthur

Conan Doyle’s magnificent Sherlock Holmes. Which of the participants

wouldn’t wish for the role of the great detective? Or at the very

least Dr. Watson? The subject matter for any such game would be

particularly difficult to handle, and what would the participants do

if

Holmes were slain? Or merely made a fool of, for that matter?

These two examples of extrapolating a game from fiction are given

only to illustrate the point about the major differences between what

makes a good game and what makes a good adventure novel. The

same applies to all works of fiction to a greater or lesser extent.

***

Delving further into the matter, we next come to the character in the

adventure. In heroic fantasy novels, each character is designed to

fit

into the tale being told, for whatever ends the author desires. Each

such

character is interwoven to form the plot fabric of the work.

Such characters make for great reading, but as absolute models for

games? Never! What AD&D player would find it interesting to play

a

wizard figure of Gandalf-like proportions? What DM would allow a

Conan into his or her campaign?

The object of the character in the fantasy adventure game is to

provide the player with a means of interacting with the scenario, a

vehicle by which the participant can engage in game activity. Each

gaming character must provide interest for the participant through

its

potential, its unique approaches to the challenges of the game form,

and yet be roughly equal to all other characters of similar level.

While novels fix character roles to suit a preordained conclusion,

game personae must be designed with sufficient flexibility so as to

allow

for participant personality differences and multiple unknown situations.

Were a designer to offer a game form in which all participants were

fighters of Conan’s ilk, participants might find it interesting at

first, but

then the lack of challenge and objective would certainly make the game

pall. If the design were then amended to allow for titanic forces to

actually threaten a fighter of Conan’s stature, the game merely becomes

one where participants start at the top and work upwards from there.

This approach seems quite unacceptable to my way of thinking,

and not necessary because it could have begun on a far more reasonable

and believable level. The same logic applies to designs which

feature any type of character as super-powerful. They are usually

developed by individuals who do not grasp the finer points of game

design, or they are thrust forward by participants who envision such

characters as a vehicle to allow them to dominate an existing game

form.

Were fighters to be given free rein of magic items in AD&D, and

spells relegated to a potency typical of most heroic fantasy novels,

for

example, then the vast majority of participants would desire to have

fighter characters. This would certainly lessen the scope of the game.

If a spell point system which allowed magic-users to use any spell

on

the lists (frequently, for what spell point system doesn’t allow for

rapid

restoration of points?!), these characters become highly dominant,

and

again most participants will naturally opt for this role.

Were clerics to be given use of all weapons and more offensive

spells, the rush would be for priest characters.

Were thieves assumed to be more brigand and less of a sneak-thief,

pickpocket character, so that they fought as fighters and possibly

wore

armor, then the majority of players would desire thief characters.

The point is, each AD&D character has strengths and weaknesses

which make any chosen profession less than perfect Choose one, and

you must give up the major parts of the other approaches. Each

character has different and unique aspects. Playing the game with the

different classes of characters offers a fresh approach, even if the

basic

problems are not dissimilar. The diversity of roles, without undue

inequality, is what makes any game interesting and fun to play.

***

In a novel, diversity is a tool for the author to use in developing

the

protagonist’s character, for highlighting the magnitude of his or her

accomplishments, as a contrast between good and evil, or whatever is

needed. A novel can easily have a magic-using fighter, a swordwielding

wizard, or a thief who combines all such aspects.

The work can just as well have the antithesis of such characters—

the inept swordsman, the bumbling, lack-power magician, the hopeless

thief who never gains a copper. The writer knows his or her aims,

and such personae are actors who follow their roles to the desired

end.

Contrary to this, in the fantasy role-playing game, characters are

the principal authors of the adventure epic which is developed by

means of the rules, the Dungeon Master’s scripting, and the players’

interaction with these and each other. With characters of too much

or

little power, the story rapidly becomes a farce or a tragedy!

By all means, do not discard heroic fantasy novels as useless to

gaming. They are, in fact, of utmost benefit! If the basis of the game

is a

setting which allows maximum imaginative input from players, and

characters’ roles are both unique and viable (as well as relatively

balanced as compared to one another), ideas for these areas, and for

all

the structure and “dressing,” are inspired from such fictional works.

With appropriate knowledge of what can only be called primary

source material as regards heroic fantasy (the classic mythology works

of Europe, et al), these novels not only engender fresh ideas, they

also

point the designer or DM toward other areas. After all, the authors

of

such works often have considerable knowledge of subject matter ideal

for use in heroic fantasy adventure gaming. Tolkien drew heavily upon

British myth, the Norse Sagas and Eddas, and even the word ent is

from the Saxon tongue, meaning giant.

There is certainly much to be learned from scholarly writers, and

they can often point the reader toward the source material they used

As

a case in point, L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt cite Faerie

Queen and Orlando Furioso as sources for parts of THE INCOMPLETE

ENCHANTER and THE CASTLE OF IRON. The latter stories are

exceptionally fine examples of heroic fantasy adventure. The former

works are excellent inspirational sources.

The “G Series” modules (STEADING OF THE HILL

GIANT

CHIEF, GLACIAL RIFT OF THE FROST GIANT JARL, and HALL

OF THE FIRE GIANT KING) were certainly inspired by the de Camp

and Pratt INCOMPLETE ENCHANTER.

The three “D Series” modules which continue

the former series

owe little, if anything, to fiction. Drow are mentioned in Keightley’s

THE FAIRY MYTHOLOGY, as I recall (it might have been THE

SECRET COMMONWEALTH—neither book is before me, and it is not

all that important anyway), and as Dark Elves of evil nature, they

served

as an ideal basis for the creation of a unique new mythos designed

especially for AD&D. The roles the various drow are designed to

play in

the series are commensurate with those of prospective player characters.

In fact, the race could be used for player characters, providing that

appropriate penalties were levied when a drow or half-drow was in the

daylight world.

The sketchy story line behind the series was written with the game

in mind, so rules and roles were balanced to suit AD&D. It is not

difficult

to write a tale based on AD&D characters, but it is difficult to

try to fit

regular characters from an heroic fantasy novel into the AD&D mold.

There are exceptions.

***

Individual characters from myth or authored mythos can be used as

special characters of the non-player sort (monsters, if you will) for

inclusion in scenarios. Most such characters can be altered to fit

into

AD&D—or rules can be bent in order to allow for them as an exceptional

case-in order to make the campaign more interestng and exciting.

That is not to say that they can be used as role models for character

types in the game—that Melneboneans, for example, are suitable as

player characters just because Elric is inserted into a scenario. This

sort

of thinking quickly narrows the scope of the game to one or two

combination-profession character types with virtually unlimited powers

and potential, and there goes the game!

So when you are tempted to allow character additions or alterations

which cite this or that work as a basis for the exception, consider

the

ultimate effect such deviation will have on the campaign, both immediate

and long-term.

Keep roles from novels in their proper place-either as enjoyable

reading or as special insertions of the non-player sort. The fact that

thus-and-so magic-user in a fantasy yam always employs a magic

sword, or that Gray Mouser, a thief, is a commensurate bladesman, has

absolutely nothing to do with the balance betwen character classes

in

AD&D.

Clerics, fighter, magic-users, thieves, et al are purposely designed

to have strengths and weaknesses which give each profession a unique

approach to solving the problems posed by the game. Strengthening

one by alteration or addition actually abridges the others and narrows

the scope of your campaign.

bloodymage

wrote:

Like Tolkien! ![]() It's unfortunate that no one approaching his level of scholarship, some

call genius, has undertaken to bring his world to gaming.

It's unfortunate that no one approaching his level of scholarship, some

call genius, has undertaken to bring his world to gaming.

The past and current offerings

don't do justice to the man's work, IMO.

![]()

Novels are not truly suitable

bases from which to create games.

The two are basicaly opposites.

Cheers,

Gary

Quote:

Originally Posted by Rakin

Gary,

Sorry for posting another question so quickly. Please don't take this as an attack, and I agree on your ideas that gaming isn't an "art" it's a game. But I can't help but notice that you also write novels in the same like settings as you would play your games in and to most writing, espeically novels, is considered art. How do you keep the 2 seperate? From maybe getting ideas for a novel in your head as you play? Or watching the gaming unfold in front of you like a fantasy novel and not go over the top and keep the game down to earth?

Howdy Pilgrim,

Allow me to respond in this manner:

Writing fiction and game mastering are not at all similar. In the former the author relates a story from beginning to end, and the reader is a spectator to events given in the work.

Game mastering requires a setting and an initial plot line, players to take the roles of the protagonists, NPCs and monsters to be the adversaries. From that beginning the players direct the action, create new plots, alter the setting by their actions, give the basis for an ex post facto story.

The sort of fiction I write

is more of a craft than an art. Shakespeare wrote artfully, and I believe

that Jack Vance does so in his genre, imaginative fiction

Cheers,

Gary