| Bibliography | - | - | - | - |

| Dragpm | - | Castles | - | Dragon 45 |

A man’s home is supposed to be his

castle, but Americans still might be surprised

to learn how numerous the fortresses were

in the Old World.

Though not quite so commonplace as

split-levels in a suburban subdivision, castles

hardly were a rarity along the medieval

European countryside. France boasted

40,000 of the sturdy facades, and Roman

legions built them every eight miles along

important routes in southwest Gaul, an

achievement even Howard Johnson’s

would envy.

Germany was home to 10,000 castles,

while today more than 450 still stand in

Poland, along with 900 in Belgium and

2,500 in Spain.

The idea did not originate with the

medieval period which we associate with

knights in shining armor and fair maidens. In

Biblical times, the walls of Jericho were 21

feet high, covered 10 acres and were surrounded by a moat 30 feet wide

and 10 feet

deep scooped from solid rock. Troy’s walls

rose 20 feet, while Rome was encircled by

12 miles of walls 12 feet thick and 60 feet

high, topped with siege towers.

In fact, at the beginning of the Middle

Ages, the construction of fortifications was a

dead art. Those citadels that were standing

were a testimony to the talents of the

Roman engineers, much of whose work was

cannibalized to construct cathedrals and

other buildings.

However, the raids of the Vikings, along

with assorted sacks and pillages by the

Magyars and Saracens and other barbarians,

spurred a new, interest in fortifications

among the kings of the era. But the attempts

by the monarchs to protect their societies

from the invading hordes backfired; the local

dukes and barons who were assigned the

task of raising and holding the fortifications

found them an excellent means of resisting

central authority as well. Feudalism flourished in the vacuum between

crumbling central authority and the anarchy wrought by

the invaders.

The goal of the fortifications strategist was

to place each castle at a point where it would

take advantage of a natural obstacle or

create a new one by its very existence.

Initially, many castles were built on high

ground where the strategic and tactical advantages of the elevated

position were combined with its ease of defense and advantage of surveillance.

Offsetting the difficulty of mounting a direct assault, mountain

castles proved hard to supply and easy to besiege.

Surprisingly, many of the more formidable castles were built on even

ground protected by marsh and/or water moats. The

watery ground made undermining extremely difficult and hampered the

moving of

siege craft near to fortress walls.

Other castles were built near fords, at

valley entrances, near bridges and close to

towns and ports. Still others were constructed

to control vital passes, valleys, and

roads, protect frontiers, collect taxes and

guard supply lines. Finally, some were built

primarily to occupy the resources of an advancing army. While it took

four attackers

for every defender to directly assault a

castle, it also required two attackers to one

defender just to besiege it.

Another consideration in the placement

of castles concerned the community around

the proposed site. It not only had to be sufficiently populated to

garrison the castle, but

also to provide for its constant upkeep.

Moats must be scraped periodically, roofs

and walls repaired, and funds raised from

the populace for these efforts.

Caermorvan Castle

The size and layout of castles was largely

the result of irregularities in the natural terrain. Castles were frequently

classified by

the shape of their layouts — circular, oval,

kidney-shaped, etc. Another classification

was based on location of its buildings. Where

interior buildings are located along the perimeter wall, castles are

known as Randhausburg types. Fortresses dominated by a tower

are termed Tower castles. By the middle of

the 13th century castles designed primarily

for luxurious living rather than defense appeared. They are known as

Schloss types.

French chateaus and the Disneyland-like

castles of Germany are examples of Schloss

castles.

After selection of the castle site, the

mobilization of huge supplies and manpower were necessary. In England

the

castle-building season was limited to between April and November. The

building of

Harlech castle in Wales during the year

1286 used the services of 170 masons, 90

quarriers, 28 carpenters, 24 smiths and 520

unskilled laborers plus a staff of 26 administrators.

Sheriffs throughout England were asked

to gather men and materials. Laborers were

often pressed into service, but each received

daily wages for his services. Two-thirds of

the expense of building most English castles

came from labor costs.

The work was long and hard, frequently

far from home. Desertion was common, and

guards were often hired to discourage this

practice. Courts governing the workers’ actions were frequently in

the hands of an administrator or chief mason. Fines or corporal

punishment awaited the lazy man and the

deserter.

While the laborers worked long hours for

little pay, men like James St. George, the

Savoyard master mason who was in charge

of Edward I’s Welsh castle-building program,

were well paid for their genius. By 1293 St.

George’s annual fees from his efforts

amounted to the equivalent of $12,000 a

year, while the total cost of the great hall and

royal apartments on Conway castle was

$200. St. George was also granted a

pension of three shillings a day for life.

The length of time needed for building a

castle varied with its size, the difficulty of access and the length

of the building season.

Conway castle, with 1,400 yards of curtain

wall 30 feet high, its protective ditch, 22

towers and three gates, was completed between 1283 and 1287 (a total

of 40 working

months).

Costs of the Welsh castles of the 13th century illustrate the low price

of labor and materials. Conway cost 19,000 pounds and

Caernarvon 16,000 pounds.

The early European castles resembled the

stockade forts of the American west. These

early fortresses were called Motte and Bailey

castles. A deep ditch was first dug around

the site. The excavated dirt was used to form

a mound (motte) inside the enclosure, the

remainder to form a counterscarp or earthen

rampart around the perimeter. A timbered

palisade of sharpened tree trunks was

planted into the rampart. Thorn bushes and

hurdles were added to make access over the

stockade painful and difficult.

A single, removable bridge proved the

sole entrance. The ditch around the enclosure was dry unless the castle

happened

to rest in a lowland or adjacent to a river.

Within its timbered walls, a nearly windowless log building housed the

feudal lord,

his family, servants, men-at-arms and

domestic animals. Called a Donjon (later

Keep or Tower), the building represented

the castle’s strong point. Varying in size from

a simple open room to a multi-story complex, it might be ringed by

yet another palisade.

Despite a vulnerability to fire, the Motte

and Bailey castles exacted a dreadful toll

upon any attacking force. Should the

archers be forced from the palisade, the defenders could withdraw to

the motte, destroying its bridge after crossing. Then they

could continue their fight from behind the

second stockade surrounding the donjon.

Should this too be breached, a final defense

could be conducted from the donjon itself.

While stone castles were developing in

France in the late 10th century, the woodenpalisaded castle remained

the typical 11thcentury fortress. Of the 100 or more castles

built in England by the Normans before the

end of the 11th century, only twelve had

any stone works. Wood castles did not require the expertise of masons.

There were

ample trees and cheap peasant labor.

Log castles could also be erected quickly

— and should one be destroyed, the remaining earthworks

and the walls

could be quickly refurbished

rebuilt. In 1139 Henry of

Bourbourg was warring against Arnold of

Adres. Henry secretly surveyed an old

destroyed castle near Arnold’s fortress. He

ordered a castle prefabricated. One

Arnold awoke to find a complete

morning

wooden

castle menacing him — one that had not

existed the night before.

The biographer of Bishop of Terouenne,

writing in 1130, best describes the contemporary castle design: “ .

. . make a hill

of earth as high as you can, encircle it with a

ditch as broad and deep as possible. Surround the upper edge of this

hill with a very

strong wall of hewn logs, placing small

towers on the circuit, according to its means.

Inside the wall plant your house or stronghold, which looks down upon

the neighborhood.”

Despite the gradual evolution toward the

stone-constructed castle from the 10th century onwards, the wooden

structure accompanied by wooden/earth defensive systems remained in use

in many Eastern

European nations until the late Middle Ages.

The Donjon of Bothwell Castle

Langeais, completed by 995, is one of the

first stone castles and possesses the earliest

known example of the rectangular donjon

(or keep). Standing on a narrow crest of a

long spur between the Loire River and the

River Roumer near Tours, France, the

donjon was a stone tower measuring 55 feet

by 23 feet. A great hall occupied the first

floor. Its walls consist of small, roughly cut

stones, regularly coursed and strengthened

by buttresses, varying in thickness according

to the direction from which an attack was

feared most likely to come.

Stone castles were introduced into

England by William the Conqueror. The

White Tower (Tower of London) was begun

in 1070. Built of Kentish rag stone, its 90-

foot-high walls varied in thickness from 15

feet at the base to 11 feet at the summit.

The advantages of stone, once discovered, spelled doom for the wooden

castle. Stone allowed a greater height of

walls, requiring less concentration of soldiers

for protection than the lower, more vulnerable earth and timber walls.

Stone was

stronger and virtually fireproof. While the

square tower corners were vulnerable to

siege pieces such as the bore, the round

towers of the 12th and 13th century corrected that situation.

The bitter struggle between Christian and

Moor for mastery of Spain gave that nation

a lead in early stone castles. The Saracens

were master builders and many of their

powerful fortifications and citadels were

further developed after Christian capture.

By the 10th century many hundred strongholds (known as alcazabas) had

been built

by the Moors.

These alcazabas consisted of irregular, encircling walls following the

natural contours

of a defensible hill. The walls were flanked

and made stronger by periodic square or

polygonal towers. Built with tapia, a mixture

of cement and pebbles poured between

boards and left to dry in the sun, extremely

strong walls were produced. Tapia proved

unsuitable for round towers.

One of the greatest of the early Spanish

castles was built by Raymond of Burgundy

at Avila, north of Toledo. Twenty French

masons were brought in to supervise. Two

masters of geometry, an Italian and a

Frenchman, designed the fortress. Nearly

2,000 Jewish, Moslem and Christian

masons worked on its walls for nine years

until completed in 1099. The castle possessed eighty rounded towers

within its

curtain walls.

As the Moors were beaten back, the captured Moorish citadels were Europeanized.

A keep was added, called a torre del

homenaje. These usually have but a single

entrance, located on the second floor, and

act as a point of final refuge. As the powers

of the new owners increased, the fortresses

were expanded and strengthened. Spain

proved to be the teacher of castle building

for the rest of Europe.

Early German and French castles, in contrast, centered their defense

around a

strongly fortified manor house. These sometimes took on the shape of

a single great

tower surrounded by defensive walls.

The continuing wars of the 12th and 13th

centuries stimulated a host of defensive innovations. Walls up to twenty

feet thick protected the lower floors.

The crenellated battlement replaced plain

parapets. The embrasures (the openings between battlements) were two

to three feet

wide and frequently had a sill (protective

wall) as much as three feet high to protect

the defender’s lower body. The battlement

(merlon) could be five to six feet wide and

six to ten feet high. The top of the battlement was angled upward,

preventing arrows

from glancing off and ricocheting into the

defenders. Many types of arrow slits were

added to the battlements. One unique embrasure had shutters hung from

hinges from

the top. The shutter was opened partially for

firing and closed when not in use.

In order to be able to deal with attackers

at the base of the wall, a timbered projection

(known as a hoarding or brattice) was added

outward from the parapet. By removing

some of the walkway planks from the hoarding, defenders could shoot

arrows, drop

stones, boiling water (even then, boiling oil

was too expensive), garbage or anything

else handy upon the attackers beneath.

This structure was eventually superseded

by the machicolation, a masonry overhang

with holes in the bottom through which missiles could be discharged.

By the second half of the 12th century,

the flanking tower became part of castle

construction. The tower enabled crossfire to

all areas around it. Based on the Roman

bastion, these towers were built at varying

intervals along the wall, projecting outward.

Arrow slits protected the archers. Many of

the towers were taller than the surrounding

walls to provide covering fire should a

portion of the wall be successfully scaled.

Continental towers frequently were capped

by steep, conical roofs, while British towers

were left open.

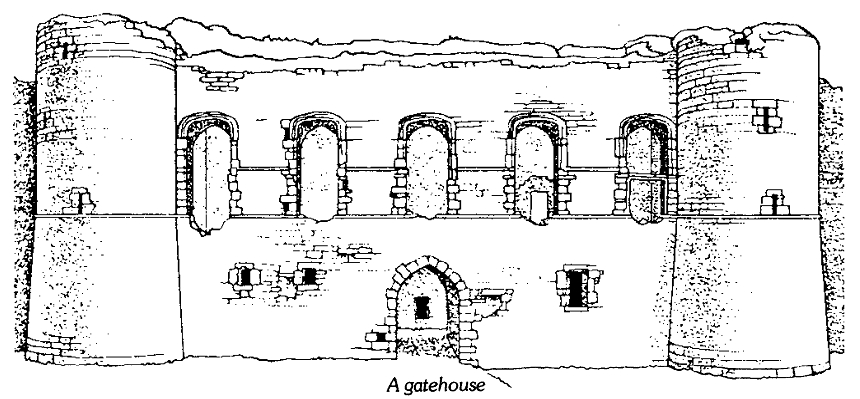

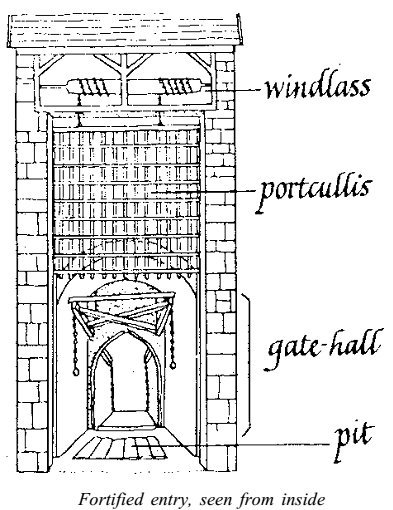

The weakest part of any early fortification

was usually the gate. The earliest gate defense was a ditch served

by a drawbridge.

The English favored a system which pivoted

the bridge around a point close to the center

of its length, one section stretching over the

ditch and resting on the far side and the

shorter inner section forming a floor across

the large, deep ditch. The inner end was

counterweighted, and the main outerleaf

could be raised quickly by chains and

pulleys, presenting an iron-sheathed underface to the attackers.

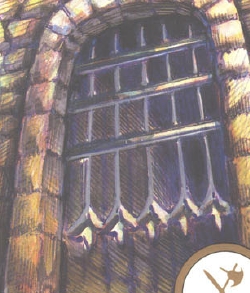

Inside the gate, the portcullis, a grid of oak

spars plated and shod with iron, could be

lowered by a pulley windlass.

Iron Portcullis of Wyndlass (92.37)

By the 13th century the barbican was introduced. In its simplest form,

it consisted of

two parallel walls built at right angles to the

gate. The barbican forced attackers to approach the gate through a

narrow, well defended passage.

With the addition of flanking towers to

either side of the gatehouse, the former

weakest point in the defense replaced the

donjon (or keep) as the castle strong point.

This allowed for more gates to be added,

providing greater freedom for defenders to

exit the castle and requiring additional manpower of the besiegers.

The typical medieval castle during the

12th and 13th centuries consisted of several

walls and multi-story donjons. However, by

the 16th century, cannon had clearly proved

more than a match for the walls of the

medieval castle. While alternative types of

fortresses developed thereafter and remarkable defenses against cannon

were created,

castle building as a defense ceased. In the

castle’s place, splendid baronial manor

houses followed, combining some of the

properties of the castle with lavish ornamentation, built primarily

to flaunt the

wealth of the owner.

B I B L I O G R A P H Y

Anderson, William, Castles of Europe, Random

House, N.Y., 1970.

Fry, Plantagenet Somerset, British Medieval

Castles, A.S. Barnes & Co., 1975.

Hindley, Geoffrey, Castles of Europe, Paul

Hamlyn Ltd., 1968.

Koch, H.W., Medieval Warfare. Prentice-Hall.

1978.

Oman, Charles W.C.. Castles, Beekman House.

1978 Edition.

Warner, Philip, The Medieval Castle. Taplinger

Publishing Co., 1971.

Wise, Terence, Forts and Castles. Almark Publications, 1972.