"Hello?

Your

Majesty?"

Communication in history and

fantasy

by Craig Barrett

-C

If you want to talk to the President of

the United States, all you have to do is

pick

up the telephone and dial the White

House. Well,

maybe it's not quite that

simple, but at least you have a fair chance

of getting the White House switchboard.

Now imagine Vespasian, Nero's general in

Judea in A.D. 67, picking up the phone

and

saying: "Give me Rome. I want to talk to

the Emperor."

Boggles the mind, doesn't it? We all

know that communicating across long

distances was just a tad more difficult

in

the ancient world than it is today. But

what that means in terms of specific details

comes as a considerable surprise. It's

not easy for us to lift our minds out of

our

own environment and cross the gap that

separates us from the minds and methods

of the people who inhabited the premodern

world.

That phrase itself, "premodern world,"

goes against the grain. Living in an age

of

constant progress -- if you bought a home

computer last year, there's a fair chance

that it's obsolescent already and obsolete

by next year -- we expect the world to

have always been like it is now. Allowing

for anomalies like the Dark Ages, a chart

of man's experience ought to show a general

upward curve of constant improvement.

But, in the communications field,

that isn't the case. From Egypt of the

Pharaohs

to Napoleonic Europe, the physical

limitations of man and animal imposed

unvarying dimensions of travel time on

all

human history. The "distance" from southern

Britain to Rome was 29 days in the

time of Julius Caesar, 29-30 days in the

12th century, and 30 days in 1834. Once

ingenuity had improved the available

methods of communications to a certain

level, a peak too fleeting in most cases

to

be termed a "plateau," there they remained.

The gap that separates that world

from ours was bridged by the advent of

the steam engine and the telegraph in the

19th century. In discussing communications

before that time, it's not necessary to

specify "Ancient," "Medieval," or "Renaissance,

-- but simply "premodern."

It requires another stretch of the mind

to understand the unpredictability and

delay that were both integral parts of

premodern

communications. Today, bad

weather is little more than an inconvenience.

When it's bad enough to upset our

timetables by as much as two or three

days, it becomes newsworthy. In the premodern

world, such delays wouldn't even

have merited a comment. Delays of three

or four days were accepted without question,

and delay of three or four weeks

were commonplace. The sudden closing of

a border or an unexpected flood could

force the re-routing of a letter through

country where no regular postal system

existed. If a route crossed any considerable

body of water, such as the Adriatic Sea

or the English Channel, delays of 30-60

days were possible. Oddly, the time between

Sicily and Spain could be shorter by

land than by sea. A state of alert, a warning

of bandits,

heavy rains, or a snowfall

might discourage couriers or even send

them scrambling in other directions. In

Outré Mer ("Beyond the Sea" -- the

Crusader

dominions in the Near East), renegades

and Bedouin tribesmen posed a

constant threat, despite efforts on both

sides of the Frankish-Moslem frontier to

patrol the highways. In Europe, the situation

was even worse

As Fernand Braudel writes in his two-volume

work, The Mediterranean (page

357), "Distances were not invariable, fixed

once and for all. There might be ten or

a

hundred different distances, and one

could never be sure in advance, before

setting out or making decisions, what

timetable fate would impose." A letter

from Spain to Italy might go by way of

Bordeaux and Lyons, or by Montpellier

and Nice. In April 1601, an ambassador's

letter from Venice to the king of France

reached Fontainbleau by way of Brussels.

The Portuguese ambassador to Rome in

the 1550s habitually sent his letters to

Portugal by way of Brussels in order to

avoid uncertainties. Philip II of Spain

wrote (Braudel, page 3571: "It is more

important that the letters should travel

by

a safe route than that four or five days

be

gained, except on occasions when speed

is

essential."

Despite these difficulties and dangers,

premodern societies did manage to keep

in

touch with each other. Four primary tools

were employed to this end (the horse post,

the foot post, the pigeon post, and the

sea)

with a number of lesser tools. What

should come as no surprise to the modern

mind is the fact that, in every case, these

tools were brought to their peak of performance

by sheer organization. In fact,

one of the earliest systems of which we

have any extensive knowledge sets the

pace and pattern for all that followed.

The horse

post

The horse-post

system of the ancient

Persians was created by Darius Hystaspis

(521-486 B.C.) to connect all the major

centers of the Persian Empire and to provide

the Great King with the most effective

means of communication that the world

had yet seen. Along already existing caravan

routes, post houses were established

at regular intervals, the intervals being

the

distance a horse could be expected to

gallop at top speed once a day (14-18

miles). Several couriers and relays of

horses were stationed at each post, and

the roads between were enhanced with

bridges, ferries, and guardhouses for

protection against bandits. While the

system itself was reserved for official

use

only (a theme repeated constantly

throughout history), the roads were open

to ordinary travelers; high-quality inns

or

caravanserais, presumably private commercial

ventures, were available at most

post stations. Letters dispatched through

the post traveled both day and night, with

a fresh rider on a fresh horse taking over

at each station to ensure maximum effort

at every stage of the journey. Such a system

could forward the official mail at a

minimum rate of 50 miles per day, allowing

for weather, and perhaps 75-100 miles

per day (where the going was good) when

top riders and horses were employed.

Five hundred years later, Caesar Augustus

(31 B.C.- A.D. 14) openly used the Persian

system as the model for the Roman public

horse and carriage post. As an added

advantage, he had the famous Roman

roads at his disposal. In time, all the

Mediterranean

world was united by these

roads: 51,000 miles of paved highways,

linked by myriad secondary roads, graced

by magnificent bridges, and crossing even

the most formidable mountain barriers.

Every Roman mile along the consular

roads, a milestone gave the distance to

the

next town; every ten miles a statio, complete

with a garrison of soldiers, offered

fresh horses; and, every thirty miles,

a

mansio combined the services of inn,

store, saloon, and brothel. Civilian travelers

could purchase "itineraries," showing

the routes and stopping places.

The post operated at all hours along

these roads, with the public stagecoaches

averaging 60 miles per day, while the

horse post (like the Persian, reserved

for

official use) averaged 100 miles per day.

Commercial mail services may also have

been available for private use, as a supplement

to hired messengers. Employing this

network of roads and stations, some remarkable

feats were possible. Julius Caesar

once covered 800 miles in eight days

by carriage. Tiberius (A.D. 14-37), riding

day and night to reach his dying brother,

made 600 miles in three days. The news

of

the death of Nero (A.D. 68-69) reached

Galba, 332 miles away in Spain, in 36

hours by messenger. After the decline of

Rome, it would be a long, long time before

Europe again experienced this level of

ease

and efficiency in communications.

For a time, the system of post roads was

maintained by the Byzantines in their

portion of the empire. The Imperial mail

system, the verdus, later became the berid

postal network of the Moslem kingdoms,

losing something in efficiency due to the

fragmentation of authority, but gaining

the

improved horsemanship of the steppe

peoples who were filtering down into the

Near East. The first great Mamluk sultan,

Baibars the Panther (1260-12771, himself

nomad-bred, reorganized the berid after

the fall of Baghdad to the Mongols, and

thenceforth its center was Cairo. Under

his direction, the berid reached its zenith,

with reports coming into Cairo twice a

week from throughout the Mamluk domain,

messages traveling at a rate of 120

miles per day.

It was in the Far East, however, united

by the conquests of Genghis Khan (1206-

1227), that the horse post achieved its

best

development in the form of the Mongul

yam. Originally a military instrument by

which the Khan kept in touch with his farflung

armies, the yam linked together

centuries-old caravan routes through

postcamps of strings of relay horses and

a

few guards, set at 50- to 100-mile intervals.

By the time of Marco Polo's visit to the

court of Genghis' grandson, Kublai Khan

(1260-1295), the interval between post

stations had closed to 25 to 30 miles,

and

the daily rate of the Khan?s couriers had

increased from 100-150 miles per day to

200-250 miles per day, with a fresh rider

and mount taking over at each station in

true relay fashion. At three-mile intervals

between horse stations, smaller villages

served the foot post and also provided

torch bearers to escort mounted couriers

so that the Khan's post could operate day

and night.

All this was under the authority of the

district daroga (road governor),

who had

absolute power to requisition whatever

was needed for the yam. Couriers also had

the power to commandeer horses at need.

Each courier carried a "gerfalcon tablet"

as his authorization -- as Baibars' riders

carried silver plaques about their necks

and yellow scarves to distinguish themselves

? and wore a wide bell-mounted

belt to alert the riders at the next station

of their approach. Unlike the situation

in

the West, Mongol carriers had no fear of

interference from brigands or renegades;

the Mongols were absolute masters of the

roads, and legend has it that the "Pax

Mongolica" was so thorough that a blonde

virgin riding a white horse and carrying

a

sack of gold could ride from one end of

the Mongol domain to the other unmolested.

As proof of the efficiency of the

post, Marco Polo relates that fruit picked

one morning in Kambalu could be served

on the evening of the following day to

the

Grand Khan at Chandu, normally a ten-day

journey away.

Without intensive organization such as

these empires used, the scope of the

mounted couriers was considerably

smaller. On the average, a single rider

cannot expect to do more than 50 to 60

miles in a day, unless he's prepared to

kill

his horse in the process. These figures

are

cited for the ancient Persians and Greeks,

the Franks of Outré Mer, and even

for the

nomads of High Asia prior to and after

the

Mongol dominion. Adverse road and

weather conditions can reduce speeds

even further. In A Wargamer's Guide

to

the Crusades, Ian Heath writes

that winter

rains could turn the roads of Outré

Mer

into quagmires of clinging mud, bringing

travel of any sort to a seven- or eight-mileper-

day crawl. Even normal winter conditions

allowed only a 30-mile day for

dispatch riders, and the fierce heat of

the

Syrian sun, permitting only eight hours

of

riding time, made 60 miles per day an

accomplishment in summer -- and this

assumes that couriers obtained fresh

horses at whatever cities and castles happened

to be located along their route.

In the West, not even token repairs had

been made on Roman highways ravaged

by war and weather. Although a regular

post reappeared in 12th-century Italy,

it

wasn't until the 13th century that Western

rulers began taking steps to turn highways

from troughs of dust and mud into usable

roads. While both religious and secular

magnates kept private couriers in personal

attendance ? the King of England had a

dozen, the King of France 100 -- it was

from the dominant commercial centers

such as Bruges and Venice that the resurgence

of good communications came.

These states were capable of sending a

letter or small package 700 miles in seven

days. By the 15th century, Venice's administration

and postal service (open to private

as well as public correspondence and

parcels, for once) was the finest in Europe.

In the 16th century, a regular postal service

was developed by Gabriel de Tassis for

the Italy-Brussels route, using the Tyrol

pass and a carefully planned itinerary.

Tassis couriers covered 475 miles in five

and a half days -- only 86 miles per day,

but a regularly achievable speed that was

considered the best in Europe at the time.

This is not to say that the mails always,

or even frequently, operated at these

peaks. When the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

(1152-1190) died in Cilicia (the

coast country of south-central Turkey)

during the Third Crusade, it was four

months before his German Reich learned

of the fact. While the word of the birth

of

the grandson of Francois I (1515-1547)

traveled 130 miles per day to reach Fountainbleau

in two days, the equally vital

news of the St. Bartholomew Massacre in

Paris (Aug. 24, 1572) traveled only 62

miles

per day to reach Madrid on September 7.

It costs money as well as interest to

make the news travel fast. For rich merchants

and governments, the news was

less a matter of luxury than of vital necessity,

and they paid the prices. Between the

neighboring cities of Venice and Ferrara,

couriers demanded a ducat per letter. One

courier sent from Chartres to Toledo and

back in July of 1560 covered 179 stages

(of

6-7½ miles each) at 54 miles per

day, and

was paid two ducats per stage ? 358

ducats. (By way of comparison, in 1538

the

hull of a war galley cost 1,000 ducats,

and

a galley cost 2,253 ducats.) Braudel tells

us

(page 365) that between Venice and Nuremberg,

the cost depended on the speed:

?4 days, 58 florins; 4 days and 6 hours,

50

florins; 5 days, 24 florins; 6 days, 25.?

(According to Will Durant, The Reformation,

page x, the florin had the same approximate

value as the ducat; in 1460, a

rich man's maid in Florence was paid eight

florins a year.)

The horse post was the most common of

the premodern communications methods,

and in some ways the surest and most

convenient. But where sheer speed was

concerned, there were better tools, and

man himself was one of them.

The foot post

Victor von Hagen writes (Realm of

the

Incas, page 177): "Man can

outlast any

animal, including the horse."

The history

of the foot post as a tool of communications

proves his point.

Ancient Greece was a land unsuitable

for horse traffic. Roads were little more

than dirt tracks; the Sacred Way from

Athens to Eleusis, the finest road available,

was only packed dirt, and narrow besides.

Streams were unbridged except by

earthen dikes that a spring flood could

easily wash away. Since no postal system

existed -- even for governments -- communication

by king and private citizen

alike was by hired runner. But these runners

could make the 160 miles from Athens

to Argos and back in a respectable two

days, and the 85 miles from Plataea (30

miles northwest of Athens) to Delphi (in

central Greece) and back was only a oneday

run.

The impact of horse, pigeon, and distance

largely eclipsed the foot post in later

European history. The runners of the

Middle Ages averaged only 20-25 miles per

day on roads that were certainly no worse

than those of the Greeks. In the Far East,

however, the Mongols established a foot

post in conjunction with their horse-post

system. The Khan's runners were stationed

in villages every three miles along

the major roads. Like the riders, the runners

wore bells attached to their belts to

warn of their approach. The system was

organized as a relay so that each runner

covered only three miles before passing

his burden on to the next man in line.

There were no horses at all in Incan

Peru when the Spanish Conquistadors

arrived (1531) to discover a mail system

that equaled or surpassed anything else

in

the premodern world. Like the Roman

system, the Incan depended on the use of

excellent roads, and the Incan roads rank

with the Roman in terms of engineering

accomplishment. At 3,250 miles, the Andean

?royal road? was the longest in the

world. Along the entire length of the desert

coast, a second arterial road stretched

2,520 miles. Lateral roads branching off

the two main arteries completed a total

of

more than 10,000 miles of major allweather

highways. Through terracing,

sophisticated drainage techniques, causeways,

step roads, bridges specifically designed

to meet specific needs, and

side-wall borders to mark the way and to

cut down on snow and wind drifts, the

Incas overcame all obstacles and virtually

eliminated all but the worst weatherinduced

delays. Incan road markers

(topos), similar to the Roman, were

set up

every four and a half miles to give distances.

Post houses (tampus) of varying

size were spaced every 18 miles in level

country, every 12 miles if the road went

up or down the side of a mountain, and

as

water allowed in desert areas. The upkeep

of this, and of the postal system itself,

was

the responsibility of the local communities.

The local communities thus provided the

trained runners who served in pairs for

15-day shifts in the chasquis (pronounced

CHAS-ki) huts (o'kla) that were

set every

one and a half miles along the roads. The

runners were badged and sworn to such

absolute secrecy concerning the mail they

handled that not even torture at the hands

of expert Spanish inquisitors could make

them betray their trust. When a message

was dispatched, each runner would carry

it only the distance to the next station

and

there pass it on -- a verbal key as well

as

the knot-string recordkeeper that served

the Incas in lieu of writing -- to the

next

runner, who would continue the relay.

These runners are chronicled as accomplishing

the incredible feat of relaying

messages from Quito to Cuzco, 1,250 miles

at altitudes ranging from 6,000 to 17,000

feet, in just five days -- a rate of 250

miles

per day! Fresh fish was sent daily 130

miles from the sea to the Lord-Inca in

Cuzco.

It's well to remember, in the face of this

achievement, that on October 27, 1985,

the New York marathon was won by one

person, not a relay, with a time of 131.5

+

minutes, approximately five minutes to

the

mile. Every Incan runner was a skilled

athlete who served in his home area so

that he could be indifferent to the altitude

and totally familiar with the three-mile

section in which he served, even to the

point of running it at full speed at night,

and all this was done on the splendid

Incan roads. Running 250 miles per day

was probably a maximum achievement,

but the average would not have been too

far below it. Contemporary Europe had

nothing to match this postal system. The

Spanish colonial government continued to

employ it until the 19th century.

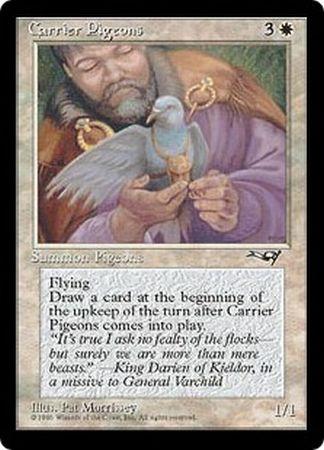

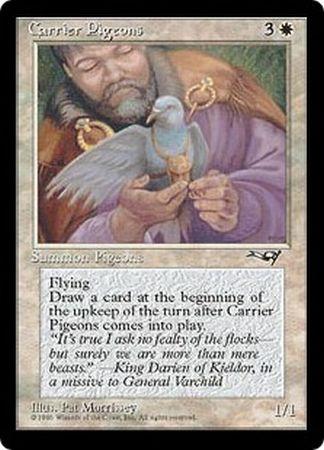

The pigeon

post

Another premodern postal system, the

pigeon post, continued in use well into

the

20th century. The discovery of carrier

pigeons aboard captured German trawlers

as early in World War I as August 5, 1914,

implying the trawlers were informants for

submarines, added significantly to the

worries of British Admiral Jellico. In

December of 1944, the ace paratroop

commander Colonel Friedrich von der

Heydte asked to take carrier pigeons along

when he landed behind American lines

during the early stages of the Ardennes

offensive. Permission was refused, and

events turned out as the colonel had

feared: the paratroopers' radios were

damaged in landing, and without pigeons,

Von der Heydte was unable to relay to his

superiors vital information concerning

American troop movements.

The use of carrier pigeons, dating back

as far as the ancient Greeks, shows up

best in the hands of the Arab and Mamluk

rulers of the pre-Crusade and the Crusading

eras. During the Abbasid (750-c. 1100)

and Fatmid (968-1171) Caliphates, the

pigeon post spanned the Arab dominions,

and top homing pigeons could sell for 700

to 1,000 dinars on the open market; the

egg of a pedigreed pigeon was worth 20

dinars (approximately 2.7 ounces of gold).

The Damascus-to-Cairo post of Nur ed-Din,

atabeg of Damascus and Aleppo (1146-

1174), used a system of "cot" stations

where letters were relayed from pigeon

to

fresh pigeon at every stage in the journey.

But the peak of this post comes, as with

the berid, under Baibars the Panther. Cot

(or loft) relay stations were established

along all the major routes of the Mamluk

domain, and the Sultan kept other pigeons

with him wherever he went, ready to

carry his orders to any part of the empire

at a moment's notice. Each pigeon flew

only the distance between the station

where he was normally kept and his home

cot, where the message was transferred

to

a new carrier. After sufficient pigeons

accumulated, the pigeons were returned

to their "ready" stations by mule transport.

The average station might house

several hundred pigeons, but the Citadel

of Cairo, the empire's communications

hub, kept as many as nineteen hundred

pigeons ready for service in its lofts.

Presumably,

some of these had their home

cots at the next relay stage along the

roads

out of Cairo, while others had their home

cots in distant cities and could be used

when considerations of speed or security

required direct contact with the Sultan?s

generals and governors. Security also

affected messages coming in to the Cairo

citadel, for some were marked for the

Sultan's eyes only, and Baibars gave instructions

that these should not be removed

by any hand other than his own.

Whether eating, sleeping, at conference,

or playing polo, the Sultan was to be notified

immediately of the arrival of these

pigeons, for every moment was critical.

The speed of pigeons varies with conditions

and from bird to bird, maximums

being approximately 60 MPH in windless

conditions and 110 MPH with a powerful

following wind; less, of course, bucking

a

strong head-wind. Letters were tied under

the wing rather than on the leg, for protection

against the weather, and pigeons

were never released at night, when hungry,

or during inclement weather, as a

precaution against their landing or wandering

between stations. Range was about

500 miles per day for ease, but relay stations

were placed closer together than

that when possible. Only male pigeons

were used as letter carriers by the Moslems.

State-owned pigeons were branded

on foot or beak, and registers were kept

showing their home cot, pedigree, value,

and history ? a formidable task, considering

the volume of pigeons in use. The

Fatmid Caliph Azeez one day decided that

he wanted to feast on the fresh cherries

of

Baalbek in Lebanon, so an order was sent

out by pigeon. Three days later, the Caliph

and his entourage feasted on 1,200 fresh

Lebanese cherries, brought to him tied

one cherry each fin a silk bag) to the

legs

of 600 pigeons.

The pigeon post has its disadvantages,

though. As Ian Heath points out, modern

magicians show how easy it is for a spy

to

secret a pigeon or two about his person,

but since pigeons fly only to their home

cots, that does no good if he has the

wrong pigeons. However vast the number

of carriers employed, you can't send a

letter if you don't have an available pigeon

tagged for the appropriate destination,

and the farther away the home cot the

longer you have to wait for the pigeon

to

be returned to you for future use. In a

fantasy world, this problem could be

overcome by a magical spell that can direct

a pigeon to the destination of the

sender's choice, or (combined with a

direction-finding or object-locating spell)

can even cause a pigeon to hunt out a

specific individual. Such spells, vastly

increasing a ruler's range of communications,

might easily be the most valuable

service a court magician could perform

for his master!

Pigeons are also limited in the weight

they can carry. Letters must be short,

expressing only main ideas or possibly

using a code where each word carries a

wider meaning for the recipient. In 1281,

when the governor of Hama sent to Sultan

Qalaoon a warning of the already-expected

approach of the Mongol army of Mangu

Timur, he said only: '?The enemy numbers

eighty thousand. Tell the sultan to

strengthen the left wing of the Mamluk

army." (Sir John Glubb, Soldiers

of

Fortune, page 112) In order

to allow for

longer messages, the Mamluks experimented

with special thin paper. Magic

could expand on this by devising psychic

messages so that merely holding the paper

could express entire paragraphs directly

to the mind of the receiver -- perhaps

even limiting the message to a specific

receiver, with no one else who handles

the

paper able to receive any message at all.

Finally, as with other posts, pigeon messengers

can be lost or intercepted. The

Guinness Rook of World Records

reports

of one pigeon released in Europe that

arrived in Australia, and another that

took

seven years to go 370 miles -- rare occurrences,

but possible. Less rare are the

chances of weather or predators bringing

down a bird -- or an enemy archer or

falconer in the right place at the right

time. The sky is a big place, and these

chances are seldom recorded as having

happened, but the danger is sufficient

that, in some cases, pigeons were released

in pairs to guard against the miscarriage

of important messages. Once more, magic

can help here, producing spells to make

carriers less detectable or to protect

them

against arrows and falcons. But then, the

magic itself may be detectable, or the

enemy may have magically controlled

falcons for "anti-pigeon" patrols. Most

important of all would be some means of

identification from the ground so

that

hunters would not accidentally bring

down their own master?s messenger

pigeons. The Sultan would not be very

happy about that!

The sea

As a highway for commerce, the sea was

and is unsurpassed. In the premodern age,

land communications, while slower and

more expensive, were usually favored

above sea communications. The latter

were simply too unpredictable. Fernand

Braudel writes (The Mediterranean, page

357): "The struggle against distance might

remain a matter of constant vigilance,

but

it was also one of chance and luck. At

sea,

favorable wind and a spell of fine weather

might make the difference between taking

six months for a voyage or completing it

in

a week or two. Pierre Belon sailed from

the Sea of Marmara to Venice in thirteen

days, a journey which frequently took half

a year.

Vessels might be forced to stop indefinitely

in safe havens when the weather

was prohibitive. In 50 B.C., Cicero waited

three weeks to cross the Adriatic from

Patras to Brindisi, and St. Paul was forced

to spend an entire winter at Malta during

one voyage. In the Middle Ages, the English

Channel crossing was known to be

particularly hazardous and timeconsuming,

varying from three days in

moderate weather to a month in bad; one

knight was kept at sea 15 days in a storm,

and landed much the worse for wear. In

January 1610, a Venetian ambassador to

England was two full weeks at Calais waiting

for the weather to abate, and, in June

1609, a Venetian ship headed for Constantinople

spent 18 days sheltering from a

storm at Chios.

Against this background, it's possible to

calculate the potential speed of voyages,

remembering that communications is a

matter for single ships rather than fleets

(which move at the speed of their slowest

members), and that record voyages are

exceptions from the norm.

"In the 4th century B.C., a favorable wind

might allow a high speed of six to seven

knots. Record voyages include 170 nautical

miles (Cotyora to Sinope, along the eastern

end of the Black Sea coast of modern

Turkey) in a day and a night; 190 miles

(Sinope to Heracleia, on the western part

of Turkey's Black Sea coast) in 2 days;

125

miles (Heracleia to Byzantion, modern

Istanbul) in 16 to 18 hours. Average speed

for a long journey with a light wind and

no halts was four to five knots (290 miles

from Lampsacos, a city on the Dardanelles,

to the Laconian Coast, the southeastern

coast of the Peloponnesos district

of modern Greece, in three days and three

nights), but usually there was no rowing

at

night and 65 to 80 nautical miles in a

16-

hour day was common in the good season.

-- Will Durant reports that some fast

Roman cruisers made 230 nautical miles

in

24 hours, but, in the 16th century, the

fastest speeds at sea were barely over

108

nautical miles in a day, under the most

favorable conditions and with elite ships.

On May 23, 1509, Cardinal Cisneros

crossed from Oran to Cartagena, 108

nautical miles, in one day, and it was

considered

a "miraculous" feat, as if he had

commanded the wind itself. Obviously, not

all things improve with age.

Well-designed ships and well-cared-for

crews (remembering that classical oarsmen

were not slaves but free) are important

factors in record voyages. Lionel

Casson writes that in the 1st century B.C.,

an ordinary vessel could make 70 nautical

miles in one day at three knots, while

a

well-made ship could make 90 nautical

miles in one day at four knots. Based on

this, he gives average speeds for ancient

vessels over open water of four to six

knots, with speed reduced during the

time-consuming tasks of working through

islands or of coasting. With a favorable

wind, a solitary trireme could average

four and a half knots (325 nautical miles

in

three days). Against the wind, the average

would be reduced to two or two and a half

knots. The Greeks also recognized that

a

trireme just out of dry-dock was faster

and more maneuverable than a ship which

had been at sea for some time and whose

timbers had become waterlogged and

heavy -- just as long-service ships in

sailing

times would be burdened with barnacles

and slower than ships which had been

freshly scraped. This problem, at least,

might be relieved in a fantasy world

where alchemists can provide a ruler's

navy with effective, water-resistant varnishes.

The formulas for the varnishes

would be state secrets, as carefully protected

as the secret of Greek Fire was by

the Byzantines, and as much sought-after

by foreign spies. Other aids from magic

could be potions to keep up the strength

of oarsmen, even at some cost to vital

life

forces, or spells to control the weather

(at

least in limited areas) so that a voyager

can

duplicate the feat of Cardinal Cisneros

and

"hold the wind in his hands." All of these

would be valuable both for dispatch boats

and fleet actions.

Exotica

In addition to the major communications

systems, some minor ones were of particular

value. Beacons -- sun telegraph, fire

telegraph, smoke signals -- can be solitary

or part of a network, and their use dates

from the first time a hostile fleet appeared

on an unguarded coast. The Romans used

torches and a simple semaphore code,

while the Byzantines had a sophisticated

heliograph system to transmit news of

invasions or disasters across the empire.

The beacon tower of Constantinople was

within sight of the emperor's residence.

A

chain of beacon towers along the coast

of

Syria in the 10th century could flash news

from Antioch to Cairo in an hour's time,

and was used later by the Mamluks to give

warning of the Mongol invasions. The

Franks heavily favored the use of beacons.

While the sites of their castles were chosen

for a variety of reasons, many were in

line of sight of each other so that messages

could be exchanged. When Saladin besieged

the Crusader castle of Kerak in

Moab (southeast of Jerusalem across the

Dead Sea) in 1183, a signal beacon summoned

relief from Jerusalem, 50 miles

away. In the maps of A Wargamer's

Guide

to the Crusades, Ian Heath

notes many

instances of this line-of-sight placement.

The use of heliographs endured so long

that Alexandre Dumas used the device in

The Count of Monte Cristo

as a means for

his title character to destroy an enemy

-- a

clear warning that telegraph operators

are

not above being bribed or otherwise interfered

with. Lacking telescopes for precision

sighting, however, probably nothing

as detailed and accurate as the modern

semaphore or the sophisticated flag codes

of the British navy was possible through

most of the premodern era.

More esoteric is a story told by Farley

Mowat in Never Cry Wolf.

Working with

an eskimo hunter named Ootek, Mowat

was startled one day when Ootek pointed

to a range of hills five miles north and

said, "Listen, wolves are talking." Mowat

heard nothing, though he noticed a nearby

wolf, asleep until then, was also watching

the hills. After listening for a couple

of

minutes, the nearby wolf raised a quavering

howl that ended on high notes above

normal human hearing. "Caribou are

coming," Ootek reported. "The wolf says

so!" And he explained that the wolf in

the

next territory north had been passing the

word -- passed to him by another wolf

even further north -- that the long

awaited caribou migration had started,

and had even specified their present location.

The nearby wolf had then acknowledged

the news and passed it further

along. Mowat was skeptical, and remained

so even when another friend named Mike

promptly went hunting, and returned

three days later with venison to spare.

The

caribou, Mike said, had been 40 miles

northeast on the shores of Lake Koiak,

exactly where the wolves said they would

be. He added that wolves could "talk"

almost as well as people and easily communicate

at great distances, and that some

Eskimos could literally converse with

them.

Coincidence? Yet an interesting story

comes from the Spanish-speaking Canary

Island of La Gomera. While the outdoor

range of a male human voice in still air

is

only 200 yards, the islanders speaking

the

whistled silbo language can, under

ideal

conditions, communicate across valleys

at

a distance of five miles (Guinness

Book of

World Records, 1975, page

46). The

Basque sheepherders and the Swiss moun-

taineers possess similar abilities. While

the

range of whistlers or yodelers depends

on

weather, altitude, and the capacity of

the

surrounding terrain to reflect or absorb

sound, the principle remains useful. This

is particularly so when a fantasy world

can combine it with animal communication,

and enhance it with low-level magic

native to given rural districts. Establishing

relay stations isn't necessary when a succession

of mountain farmers and herders

who are used to "talking" to each other

are able and willing to pass the news along

in this way! Allowing for the general conservative

attitude of scientists and researchers,

we can even consider the

five-mile range to be normal rather than

exceptional, with wolves able to "talk"

even farther.

Another method of rural communication

is the somewhat more specious notion of

Robin Hood's famous "whistling arrows,"

used to speed messages across Sherwood

Forest. The premodern record for long

shooting belonged to Sultan Selim III (953

or 972 yards in 1798), while the 1975

records are held by Harry Drake of Lakeside,

California: 856 yards 20 inches with

the handbow, 1,359 yards 29 inches with

the crossbow, and 1 mile 101 yards 21

inches with the footbow (Guinness,

page

494). If we accept that Robin Hood's men

could fire an arrow 880 yards through the

forest sky, that requires two men per mile

who must be in a specified locale at a

specified time to speed the message on

its

way. Such a method is a little wasteful

of

manpower, but could be valuable to get

important information across dangerous

terrain, and to do it secretly. The trick

would be arranging for enough top-grade

archers to be where the arrows are landing

just when they're needed. In heavy

forest country, where isolated farms are

virtually immune to interference and

where the necessarily fixed nature of road

travel guarantees that your lines of communication

will remain static, the procedure

almost makes sense.

In realms of pure fantasy, an enormous

number of devices, perhaps not originally

intended for the purpose, can serve as

tools of communication. The fabled "Seven

League Boots" that enable the wearer to

cover 21 miles at a single stride would

be

invaluable for special couriers. The "talaria"

or winged sandals of Hermes would

also be of use. The wings of Daedalus,

manufactured to allow him and his son

Icarus to flee Crete, and fatal to Icarus

when he flew too close to the sun and the

melting wax of the wings plunged him into

the sea, could be employed. The trouble

with devices like these is that they?re

usually one-of-a-kind items. They may

serve for a single individual, the prime

courier of a god or a king, but they hardly

allow for a communications network.

The same holds true for flying creatures,

such as a roc or a pegasus tamed to

the use of man. Unless you have an entire

herd of them, you can't expect to set up

a

postal relay, and if you do have an entire

herd, as Lew Pulsipher makes clear in his

article, "The

Fights of Fantasy" (DRAGON®

issue #79), you have better uses for them

than making mail runs. In addition, creatures

large enough to carry a man through

the sky have other liabilities. They're

a lot

more visible than pigeons, haven't any

chance of blending "anonymously" into

their surroundings, and make inviting

targets for any mage with the power to

strike at them.

Other courier techniques might include

teleportation, dimension doors, some sort

of potion to increase the speed with which

a man or a horse can run (at some cost

to

life energy), or even supernatural messengers

or astral travel. At sea, dolphins can

make 40 to 60 knots and are six to ten

times faster than the fastest dispatch

boats, if you can control them. All have

advantages and disadvantages (overkill

being one of the latter). For emergency

use, when you take chances and pay

prices you wouldn't normally consider,

all

may be viable.

Crystal balls armed with clairaudience

and ESP offer more promise. Just half a

dozen can link major cities and fortresses

together. For independent mages, the

difficulty in using them would be arranging

to have both sending and receiving

parties on-line simultaneously, in an age

when "synchronize your watches" has no

significance. But, in the case of societies

analogous to the Templars, Hospitalers,

or

Assassins of the Crusading era, it's entirely

conceivable that trained adepts would be

standing by, day or night, to receive messages.

Dedicated monks would have no

problem with this, and conditions of perpetual

warfare such as existed in Outré

Mer during the Crusades would provide

incentive for the duty.

Last, but very far from least, there?s that

most excellent message system popularized

by the TV series "M*A*S*H" -- the

"latrino-gram." Rumor and scuttlebutt can

be remarkably accurate, and can travel

faster even than the speeding news release.

Given the security skills of the premodern

world -- or even of the modern

world, some would say -- it's not impossible

that at the moment a special courier

is whispering a top-secret message into

the

king's ear up in the palace, the bosun

of

the ship that brought the courier is regaling

his companions in the local tavern

with precisely the same tidbit of juicy

gossip. In ancient Greece, commercial

information services developed in the

larger ports, fed by hard news and soft

rumor gleaned from incoming ships and

caravans. Gustave Glotz writes (Ancient

Greece at Work, page 293):

"Those firms

which had correspondents at a certain

number of centers could form a private

information agency." The same would hold

true for all ages and all societies, and

for

trade centers located inland as well as

on

the coasts. The medieval Jews had an

international information network second

to none. Kings could hardly match rich

merchants in this potential and were

prepared to buy and sell news through

these unofficial organizations. Never underestimate

the power of unauthorized

intelligence dissemination!

Be it by courier or ship, crystal ball or

gossip, the news has a way of getting

around. This has been a mere sampling of

the more prominent methods our premodern

ancestors used to help it on its way. In

the following article are some tips on

how

those methods can be translated into

fantasy role-playing terms. But don?t be

afraid to experiment on your own. You

just might come up with something

nobody?s ever thought of before.

Bibliography

Braudel, Fernand. The Mediterranean.

New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Casson, Lionel. Ships and Seamanship

in

the Ancient World. Princeton:

(no publisher),

1971.

Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ,

from

The Story of Civilization,

Vol. III. New

York: Simon & Schuster, 1954.

Durant, Will. The Age of Faith,

from The

Story of Civilization, Vol.

IV New York:

Simon & Schuster, 1954.

Durant, Will. The Reformation,

from

The Story of Civilization,

Vol. VI. New

York: Simon & Schuster, 1957.

Elstob, Peter. Hitler's Last Offensive.

New York: Ballantine Books, 1973.

Glotz, Gustave. Ancient Greece at

Work.

London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd.,

1965.

Glubb, Sir John. Soldiers of Fortune.

New York: Stein & Day, 1973.

Heath, Ian. A Wargamer's Guide to

the

Crusades. Cambridge: Patrick

Stephens,

1980.

Lamb, Harold. Genghis Khan.

New York:

Bantam Books, 1963.

McWhirter, Norris, and Ross McWhirter.

Guinness Book of World Records --

1975.

New York: Bantam Books, 1975.

Mowat, Farley. Never Cry Wolf.

New

York: Dell Publishing Co., 1977.

Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco

Polo.

trans. William Marsden. New York: Dell

Publishing Co., 1961.

Pulsipher, Lew. "The

Fights of Fantasy,"

DRAGON Magazine 79 (November,

1983).

Rawlinson, George. The Seven Great

Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern

World,

Vol II. New York: Hooper, Clarke &

Co. (no

date given).

Tuchman, Barbara. A Distant Mirror.

New York: Ballantine Books, 1978.

Tuchman, Barbara. The Guns of August.

New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1969

Von Hagen, Victor. Realm of the Incas.

New York: The New American Library,

1961.