Good isn't stupid,

Paladins & Rangers,

a n d

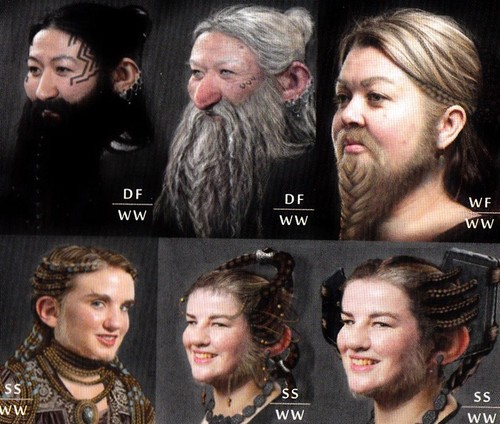

Female dwarves do

have beards!

Gary Gygax©

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon 38 | - | Best of Dragon, Vol. II | - | Dragon |

There seems to be a continuing

misunderstanding amongst a

segment of Advanced

D&D players as to what the term ?good?

actually means. This problem

does cut both ways, of course, for if

good is not clearly defined,

how can evil be known? Moral and

ethical precepts are based

on religious doctrines, secular laws, family

teachings, and individual

perceptions of these combined tenets. It

might be disturbing if one

reflected deeply upon the whys and

wherefores of the singular

inability of so many players to determine

for themselves the rights

and wrongs of good behavior?unless one

related this inability to

the fact that the game is fantasy and therefore

realized (rationalized?)

that this curious lack must stem from the

inability to draw a parallel

between daily life and the imagined

milieu. In order to clear

the record immediately, then, and define the

term ?good? for all participants,

it means everything defined in the

dictionary as augmented

and modified by one?s moral and ethical

upbringing and the laws

of the land!

Gentle Reader, if you are

in doubt about a certain action, and this

applies particularly to

all who play Rangers and Paladins, relate it to

your real life. It is most

probable that what is considered ?good? in

reality can be ?good? in

fantasy. The reverse is not quite so true, so

I?ll quantify things a bit.

Good does not mean

stupid, even if your DM tries to force that

concept upon you. Such assertions

are themselves asinine, and

those who accept such dictates

are stupid. To quantify ?good,?

however, we must also consider

the three modifiers in AD&D:

1) lawful, 2) neutral,

3) chaotic.

1) The lawful perception

of good dictates that the order which

promotes the greatest good

for the greatest number is best. It further

postulates that disorder

brings results which erode the capability of

bestowing good to the majority.

Therefore, without law and order,

good pales into nothingness.

2) Good from the neutral

perception is perhaps the purest sort,

in that it cares not for

order or individual freedom above overall

good, so there are no constraints

upon the definition of what is good.

Whatever accomplishes the

good result is acceptable, and the means

used should not be so fixed

as to bring bad to any creature if an

alternative way exists which

accomplishes the desired good without

bringing ill to others?or

better still, brings good to all in one degree

or another.

3) The chaotic

views good from an individual standpoint, of

necessity. The very stuff

of chaos is individual volition, freedom from

all constraints, the right

of person above all else. Good is first and

foremost applied to self;

thereafter to those surrounding self; lastly to

those furthest removed from

self?a ripple effect, if you will. It is

important to understand

that ?good? for self must not mean ?bad?

for others, although the

?good? for self might not bring like benefits

to others-or any benefit

at all, for that matter. However, the latter

case is justifiable as ?good?

only if it enables the individual to be in a

better position to bring

real ?good? to others within the foreseeable

future.

One of the advantages of

AD&D over the real world is that we do

have pretty clear definitions

of good and evil?if not conceptually (as

is evident from the necessity

of this article), at least nominally.

Characters and monsters

alike bear handy labels to allow for easy

identification of their

moral and ethical standing. Black is black, gray

is gray, white is white.

There are intensities of black, degrees of

grayness, and shades of

white, of course; but the big tags are there to

read nonetheless.

The final arbiter in any

campaign is the DM, the

person who figuratively

puts in the fine print on these alignment

labels, but he or she must

follow the general outlines of the rule book

or else face the fact that

his or her campaign is not AD&D. Furthermore, participants

in such a campaign can cease playing. That is the

surest and most vocal manner

in which to evidence displeasure with

the conduct of a referee.

In effect, the labels and their general

meanings are defined in

AD&D, and the details must be scribed by

the group participating.

Perceptions of good vary

according to age, culture, and theological training. A child sees no good

in punishment meted out by

parents-let us say for playing

with matches. Cultural definitions of

good might call for a loud

belch after eating, or the sacrifice of any

person who performs some

taboo act. Theological definitions of

good are as varied as cultural

definitions, and then some, for culture

is affected by and affects

religion, and there are more distinct religious beliefs than there are

distinct cultures. It is impossible, then, for

one work to be absolute

in its delineation of good and evil, law and

chaos, and the middle ground

between (if such can exist in reality).

This does not, however,

mean that ?good? can be anything desired,

and anyone who tells you,

in effect, that good means stupid, deserves a derisive jeer (at least).

The "Sage

Advice" column in The Dragon #36 (Vol. IV, No. 10,

April 1980) contained some

interesting questions and answers regarding ?good? as related to Paladins

and Rangers. Let us examine

these in light of the foregoing.

A player with a Paladin character

asks if this character can "put

someone to death (who) is

severely scarred and doesn?t want to

live." Although the

Sage Advice reply was a strong negative, the

actual truth of the matter

might lie somewhere else. The player does

not give the name of the

deity served by the Paladin. This is the key

to lawful good behavior

in AD&D terms. Remember that ?good?

can be related to reality

ofttimes, but not always. It might also relate

to good as perceived in

the past, actual or mythical. In the latter case,

a Paladin could well force

conversion at swordpoint, and, once

acceptance of ?the true

way? was expressed, dispatch the new

convert on the spot. This

assures that the prodigal will not return to

the former evil ways, sends

the now-saved spirit on to a better place,

and incidentally rids the

world of a potential troublemaker. Such

actions are "good," in these

ways:

1. Evil is abridged (by at

least one creature).

2. Good has gained a convert.

3 . The convert now has

hope for rewards (rather than torment)

in the afterlife.

4. The good populace is

safer (by a factor of at least 1).

It is therefore possible

for a Paladin to, in fact, actually perform a

"mercy killing" such as

the inquiring player asked about, provided

the tenets of his or her

theology permitted it. While unlikely, it is

possible.

Another case in point was

that of a player with a Paladin character who wishes to marry and begin

a lineage.

Again, our "Sage Advisor"

suggests a negative. While many religions forbid wedlock

and demand celibacy, this

is by no means universal. The key is again

the deity served, of course.

DMs not using specific deities will harken

back to the origin of the

term Paladin and realize that celibacy is not a

condition of that sort of

Paladinhood. Also, although the Roman

Catholic church demands

celibacy of its priests, the doctrines of

Judeo-Christianity hold

matrimony and child bearing and rearing as

holy and proper, i.e. "good."

So unless a particular deity demands

celibacy of its fighter-minions,

there is no conceivable reason for a

Paladin not to marry and

raise children. This is a matter for common

sense--and the DM, who,

if not arbitrary, will probably agree with

the spirit of AD&D

and allow marriage and children (This must be a

long-range campaign, or

else its participants are preoccupied with

unusual aspects of the game.

No matter . . .)

The third inquiry concerned

a Ranger character. The writer

claimed that his or her

DM combined with a lawful good Ranger to

insist that a wounded Wyvern

was to be protected, not slain, unless it

attacked the party. Here

is a classic case of players being told that

(lawful) good equates with

stupidity. To assert that a man-killing

monster with evil tendencies

should be protected by a lawful good

Ranger is pure insanity.

How many lives does this risk immediately?

How many victims are condemned

to death later? In short, this is not

"good" by any accepted standards!

It is much the same as sparing a

rabid dog or a rogue elephant

or a man-eating tiger.

If good is carefully considered,

compared to and contrasted with

evil, then common sense

will enable most, if not all, questions

regarding the behavior of

Paladins and Rangers to be settled on the

spot. Consideration of the

character?s deity is of principal merit after

arriving at an understanding

of good. Thereafter, campaign ?world?

moral and ethical teachings

on a cultural basis must rule. These

concepts might be drawn

from myth or some other source. What

matters is that a definition

of ?good? is established upon intelligent

and reasonable grounds.

Viewpoints do differ, so absolutes (especially in a game) are

both undesirable and impossible.

OUT ON A LIMB

The discussion of Goodness

and intelligence

in the Sorcerer’s Scroll underlines the

need for every campaign to have a mythos, a

set of Gods, a set of religions—something for

the clerics and paladins to worship and serve.

But the Gods and the mythos should be cut

from whole cloth. Craig Bakey did an excellent

job of this in his article “Of the Gods”

(TD-29). Using real-world religions and

Gods gets the real-world worshippers very

upset (as well it should!) and warps and limits

the campaign.

Erol K. Bayburt

Troy, Mich.

(Dragon #41)

* * *

There are areas where AD&D

can be absolute, places where

statements can be accepted

as gospel. One such is that of the facial

hirsuteness of female dwarves.

Can any Good Reader cite a single

classical or medieval mention

of even one Female dwarf? Can they

locate one mention of a

female dwarf in any meritorious work of

heroic fantasy (save

AD&D, naturally)? I think not! The answer is so

simple, so obvious, that

the truth has been long overlooked. Knowing the intelligence of AD&D

players, there can be no doubt that all

will instantly grasp the

revealed truth, once it is presented, and extol

its virtue.

Female dwarves are neglected

not because of male chauvinism

or any slight. Observers

failed to mention them because they failed

to recognize them when they

saw them. How so? Because the

bearded female dwarves were

mistaken for younger males, obviously!

It is well known that dwarves

are egalitarian. They do not discriminate against their womenfolk or regard

them as lesser creatures,

and this is undeniable.

Furthermore, dwarves do not relegate females to minor roles. There can

be no doubt that during any important activity or function, female dwarves

were present. An untrained eye would easily mistake the heavily garbed,

armored, shortbearded females for adolescent males. So happened the dearth

of

information pertaining to

the fairer sex of dwarvenkind. Now, do

female dwarves have beards?

Certainly! And male dwarves are darn

glad of it, for they

do love to run their fingers through the long, soft

growth of a comely dwarven

lass.

THE FORUM

I have been following the current ?good?

discussion with some curiosity

of late. It seems

that the two groups discussing

the topic are either

of the opinion that there

is only one ?good?

which is a definition of

moralistic and ethical

actions and behavior, or

that ?good? is relative to

the individual involved.

I hold the opinion of the

former group, where

?good? defines a certain

means of acting in

relationship to all others,

in that killing is evil

unless it prevents the occurrence

of further evil,

where honesty and integrity

are important, where

the swing of preference

is based more on the

group, as opposed to the

individual (although this

is contained somewhat in

law and chaos, I think

it does find some association

with good and evil

as well).

However, one has to remember

that killing any

creature that stands in

one?s way just to derive

the benefit of a few gold

coins, or the boost of the

ego that killing might provide,

may be right as far

as the creature concerned

goes. It isn?t good;

such an action definitely

is an evil one in regards

to both the creature involved

(let us suppose, for

example, an orc) and a good

creature viewing the

same situation (perhaps

a paladin or ranger). The

orc knows his actions are

evil, but by the same

token, they are also right

and further the ends

that the orc wishes to obtain

(even if those ends

are based largely on instinct

and fear as opposed

to intelligent decision).

In the same manner is the

case [of] a paladin who

is about to deliver the

death blow to, say, a chaotic

neutral thief, who

might have been attempting

to steal items from

the paladin, or trying to

backstab him (or her) to

steal items from him. Combat

might be necessary

for self-defense and should

the paladin get to a

situation where the thief

surrenders, the paladin

may well let the thief go

as long as his safety were

not in jeopardy. This is

a fundamentally good act,

as the paladin is sparing

the life of another creature,

and this being may well

appreciate the

doings of the paladin and

in turn begin to embrace

the lawful good ethos due

to its good treatment

of the thief. However, to

an evil demon, this

would be a wrong act. It

would be proper to kill

the thief, since he cannot

be trusted, and it helps

clear the demon?s mind about

paltry backstabbers

like this (even if the demon

is one himself . . . .).

What I?m basically trying

to say, perhaps, is

that we should try to distinguish

?right? and

?wrong? from ?good? and

?evil.? They are not

necessarily the same, even

though they could be.

Good and evil are predefined

standards by which

all other creatures are

measured; right and

wrong, descriptors which

vary from individual to

individual. It?s important

to keep this in mind, as

it appears this discussion

is becoming fairly

heated and has probably

stirred the thoughts of

many a group of campaigners.

Jim MacKenzie

Regina,

Sask.

(Dragon #108)