Irresistible Force

A Brief Account of the Rise of

the Swiss Confederation

with Commentary on Their Military

Tactics

Gary Gygax

-

-

Gary informs us that while “Gygax is an ancient Swiss name,” the

name means “see-saw,” or “up-and-down,” in Macedonian. In any

event, the author’s father was born in Canton Bern, Switzerland,

so he is

more than usually interested in the military history of that country.

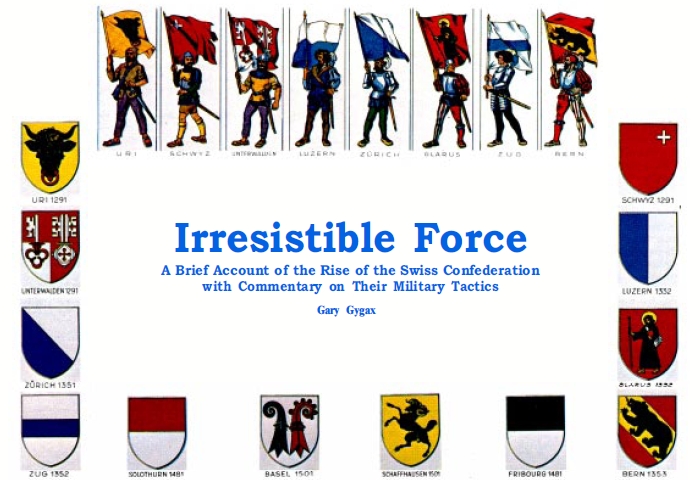

The three “Forest Cantons” concluded an “Everlasting League” in

1291 A.D. Schwyz, Uri, and Unterwalden defied the Hapsburg counts

and set upon a course of independence which would eventually

establish modern day Switzerland. The process would involve them in

numerous wars in self defense, aggression, and even civil strife. In

general,

these districts has an historical basis of self-rule directly under

the

German Holy Roman Emperor. What seems to have triggered the Confederates’

struggle for complete independence is connected with the rise

of a petty noble family from the same area. The Hapsburg family of

Aargau were becoming powerful landlords, and they claimed rights in

the League’s area which the Confederates refused to yield. The League

supported rivals of the Hapsburgs for election as Emperor, and the

dispute

eventually resulted in the Battle of Morgarten in 1315. The

Hapsburg Leopold I of Austria led an army purported to number

15,000 into the Valley of Schwyz. This force was strung out along a

narrow,

icy road paralleling Lake Aegeri, and Swiss mountaineers, said to

have numbered only 1,500, first rolled boulders and logs upon the invaders

from their ambush, and then fell upon the head of the column,

slaughtering the knights and routing the foot behind. The Confederates

won for themselves virtual independence by this crushing defeat of

Duke Leopold, but this was certainly no guarantee of immunity from

further aggression from the powers (Austria, France, Burgundy, Savoy,

Germany, Milan) which surrounded the little territories, nor did it

spell

any slackening of desire on the part of the Swiss to confine their

domain

to the lands gained by the victory at Morgarten.

The Bernese (or Berners) allied with the three Forest Cantons and

were a major factor in the next major battle fought, Laupen, in 1339,

against a Burgundian force invading the Aar valley. While the men of

Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden employed many halberds (as well as

morning stars and two-handed swords), their new allies favored the

pike, and it was these Berners and their associates who turned the

tide at

Laupen — overcoming the Burgundian foot and then driving off the

cavalry pressing upon the halberd-armed contingent of herdsman from

the Forest Cantons. This battle was decisive enough to win a respite

of

several decades, and during this time the Confederacy grew by the additions

of Luzern (1332), Zurich (1351), Glarus (1352), Zug (1352), and

Bern (1353). Note that these dates are when these areas joined the

league as formal members (although not necessarily as allies of each

member), not the dates of first co-operation or alliance with the Forest

Cantons. The Confederation grew to include Fribourg (1481) and

Solothurn (1481), then Basel (1501) and Schaffhausen (1501), and

finally Appenzell (1513). Territory which was granted cantonal status

later (Aargau, Graubunden, St. Gallen, Thurgau, Ticino, and Vaud in

1803; Geneve, Neuchatel, and Valais in 1815) was under Swiss control

or associated as allies, by and large, during the 14th or 15th Centuries;

for the various members of the Ancient League of High Germany, (the

Swiss) often provoked attack by their territorial acquisitions. This

is not

to say that the citizens of the areas which the Confederates acquired

were conquered peoples, for even as dependents of a member of the

Confederacy they were far better off than under the feudal suzerains

of

France, Germany, etc.

Important Battles of the Swiss

A brief listing of the major battles for national sovereignty fought

by the

Swiss after Laupen contains a dozen engagements:

| Year |

Battle |

War |

Victor |

Special Feature or Result |

| 1386 |

Sempach |

Austrian-Swiss |

Swiss |

Leopold III killed |

| 1388 |

Nafels |

Austrian-Swiss |

Swiss |

Ambush with logs and boulders a la Mortgarden |

| 1422 |

Arbedo |

Swiss-Milanese |

Milan |

Condottiere dismount to fight as infantry using their lances as pikes |

| 1444 |

St. Jacoben Birs |

French Invasion |

France |

600 Swiss die to a man fighting 30,000, French lose 2,000 and turn

back |

| 1474 |

Hericourt |

Swiss-Burgundian |

Swiss |

- |

| 1476 |

Grandson |

Swiss-Burgundian |

Swiss |

- |

| 1476 |

Morat |

Swiss-Burgundian |

Swiss |

- |

| 1477 |

Nancy |

Swiss-Burgundian |

Swiss |

Charles the Rash killed, Burgundy absorbed by the French. |

| 1478 |

Giarnico |

Swiss-Milanese |

Swiss |

- |

| 1499 |

Frastenz |

Swiss-Swabian |

Swiss |

- |

| 1499 |

Calven |

Swiss-Swabian |

Swiss |

Graubunden becomes independent |

| 1499 |

Dornach |

Swiss-Swabian |

Swiss |

Last invasion of Swiss territory until the Napoleonic Era |

The many Swiss victories so enhanced the repute

of the phalanxes of Confederate

infantry, that all the nations of Europe roundabout

enlisted corps of

mercenary Swiss pikemen and halberdiers — furnished,

of course, by the

various cantons. Switzerland had at last found

an exportable commodity which

brought them silver in return. The notable battles

they engaged in were:

| Battle |

Opponent |

Result |

| 1502, Barletta |

Spain |

Swiss pikemen defeated by sword and

buckler infantryman at close quarters; first

French loss to Spain |

| 1513, Novara I |

French |

Swiss break rival landsknechte formation

to win battle and slay all the German

prisoners. |

| 1515, Marignamo |

French |

Swiss forced into square by cavalry charges

while cannons play on their formations;

they withdraw |

| 1522, La Bicocca |

Holy Roman Empire |

Swiss charge entrenched landsknechte,

and in the ensuing attempt to gain the upper

works lose 3,000 men and retire |

| 1525, Pavia V |

Holy Roman Empire |

French and Swiss besieging city are weak-

ened by musketry and then driven from the

field by Spanish sword and buckler infantry |

Switzerland became independent because its “rude farmers and

herdsmen” took up arms and fought. This infantry faced all sorts of

opponents,

including the superbly armored feudal heavy cavalry, and won

with ease. The “loss” of the battle at St. Jacob-en Birs shook the

French

Dauphine to the core, for his cavalry was helpless against the Swiss,

and

it was through repeated missile volleys and dint of costly fighting

that his

army finally overcame a mere handful of infantry who refused to yield.

The lances of the dismounted cavalry of Carmagnola at the Battle of

Arbedo, as well as their better armor, nearly won the day for the

Milanese, and the Swiss certainly withdrew with alacrity, but thereafter

a

greater percentage of pike (rather than halberd) armed troops were

in

each contingent of Swiss who took the field. During the Swiss-Swabian

War (beginning in 1498), a body of 600 pikemen were caught in the

open by the Swabian horse formed a “hedgehog” and repelled the

enemy charges with “much laughing and jesting” — the infantry was

outnumbered by nearly two to one. The reputation of absolute

fearlessness, terrible ferocity in battle, and the irresistible onset

of the

pike squares caused the Swiss to become the most feared, imitated,

and

admired troops in Medieval Europe. They too must have begun to

believe that “God is on the side of the Confederates.” They took the

same attitude in battle when serving as mercenary troops, and for a

short

time after they were totally independent, they remained the arbiters

of

battle. While the Swiss certainly were instrumental in bringing infantry

back into ascendency over cavalry, changing modes of warfare also

doomed their arms to come to ruin as the Renaissance began. They

defeated the great powers which surrounded Switzerland and won

freedom with their halberds and pikes, but on later fields of battle

the

Swiss found that generalship eventually prevails over outmoded tactics

no matter the elan or bravery of the soldiers using them.

Swiss Military System and Tactics

The men of the three original cantons were primarily halberdiers.

The troops from the lower lands of the Confederation — Berners,

Lucerners, and others from the Aar Valley favored the pike. With these

infantrymen were numbers of light troops, crossbow or arquibus armed

skirmishers. There was never a significant number of cavalry in a Swiss

national force, although there were some such troops furnished by the

knights and gentry of Canton Bern. Where possible, the Swiss made use

of artillery, although their typical swift movement through hilly and

mountainous terrain precluded this most of the time. A typical Swiss

field army would be composed as follows:

| Troop Type |

Weapon |

Percentage of Force |

| infantry |

halberd |

20%-60% |

| infantry |

lucern hammer, morningstar, or two-handed sword |

10%-20% |

| infantry |

pike |

10%-65% |

| infantry |

crossbow |

5%-30% |

| infantry |

arquibus |

5%-25% |

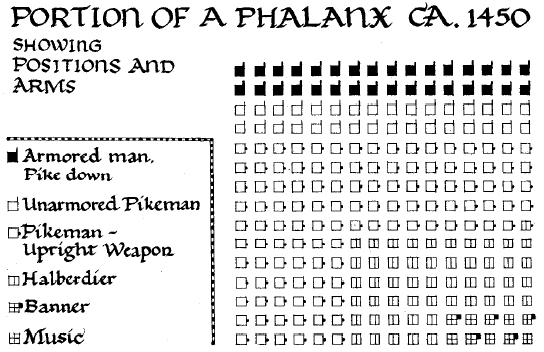

Halberdiers predominate in early battles, but later they become

fewer,

and c. 1450 they form the center of the pike squares and represent

only

20% to 30% of the total force.

Lucern hammers, morning stars, and two-handed swords were eventually

abandoned totally by the Swiss in favor of the halberd. Forces c.

1450 and after will have few (if any at all) of such weapons, the morning

star being the first to be abandoned.

Pikes begin to dominate the Swiss arms after Arbedo (1422), and

thereafter at least 50% of their force are so armed.

Crossbows give way to arquibuses c. 1450, although it is likely

that some

persisted until 1500.

Cavalry fielded was typical of the period, armored riders bearing

lance

and various secondary arms. It is doubtful that the Swiss ever fielded

more than a few score cavalry, so an upward limit of 100 to 200 must

be

placed upon the percentage maximum.

Swiss infantry were generally lightly armored. This was initially due

to the fact that they could afford none, but the benefits of mobility

soon

gave the Confederates the determination not to add such encumbrance

to their formations. Officers wore full panoply and rode to battle

in order

to keep pace with the rest. Halberdiers and the like wore metal helmets,

cuirasses or metal or leather, and a few also wore light greaves. Most

pikemen wore felt hats or metal helmets and padded or leather

cuirasses. Only the front rank or two of any phalanx had metal armor.

Light infantry were similarly equipped, although most were totally

unprotected

save for helmet and leather cuirass.

Logistics were no problem for the Swiss. Within two to four days,

each area could raise its levy and be ready to march, each man carrying

a few day’s supply of food with him (the rest could be scavenged from

the land). The bodies of troops then marched swiftly to predesignated

meeting places, joined, and were in the field and ready for battle

far

more quickly than any invader could hope to counter. As mentioned

previously, the leaders of the contingents rode, so that their heavy

plate

armor would not slow the infantrymen. As these levies were national,

each man knew his neighbor in formation and often elected their

leaders. Each man knew his place and what to do.

The sight of a Swiss column must have been impressive indeed, for

it moved so quickly but looked like a forest with the tall pikes held

upright

except towards the front and the dozens of banners — perhaps the great

white cross of the Ancient League of High Germany accompanying the

cantonal, town, district, guild and association flags. These phalanxes

moved without noise, except when the troops gave voice to their battle

shout just before impacting upon the enemy — or fending off fruitless

attacks

by desperate cavalry. Since the enemy knew full well that the Swiss

would give no quarter and that they were absolutely determined to

triumph, it took great discipline and courage indeed to stand before

the

onslaught of such troops.

Tactics employed by the Confederates were at first fresh and

innovative. The Flemish at Courttai (1302) used pikemen to defeat the

horsed chivalry of France, but this was due to skillful positioning

of the

infantry so as to take advantage of the waterways and soft ground,

as

well as the French failure to allow their mercenary Genoese crossbowmen

employment, as Mons-en Pevele (1304) and Cassel (1328) amply

prove. The mountaineers of the Forest Cantons likewise used terrain,

plus surprise by ambush and avalanched boulders and logs (much as

their ancient kinsmen had before them) to defeat heavy cavalry.

Although few pikemen were involved, the men of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden

formed a solid phalanx to fall upon the head of the Austrian

column and complete the work prepared by the ground and ambush.

Morgarten was a battle in which the Swiss showed extraordinary tactical

skill, and this unusual demonstration of ability continued.

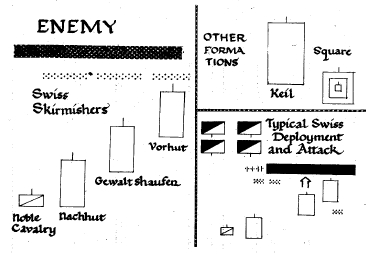

At Laupen, the Burgundians squared off against infantry totally

unsupported by cavalry. Perhaps they envisioned treating the Swiss

to

the same rough handling the French had given the Flemish just eleven

years earlier. This battle is worth discussion in some detail, for

it is the

first in which the Swiss used three phalanxes (Vorhut, Gewaltshaufen,

Nachhut) in echelon to confront the enemy — a deployment which

became

the rule after 1339. Count Gerard of Vallangin commanded a

feudal array of Burgundian horse and foot which numbered 15,000.

With it he invaded Confederate territory and laid siege to the town

of

Laupen, near Bern. The Swiss rapidly rose a relief force and marched

to

a position on high ground which overlooked the besieging force.

Rudolph von Erlach was in sole command of the Swiss army (an

unusual situation), and he arrayed it with the halberdiers of the Forest

Cantons in the left phalanx, the Bernese pikemen the center, and

Bernese allies the right. The Burgundians deployed all of their horse

opposite the Swiss left (perhaps noting that this square did not have

many pikes, as the latter weapon is obvious from a great distance)

and

were allowed to begin advancing up the slope, the Bernese-allies being

opposed by the Burgundian infantry levies. As soon as the enemy commenced

their foreward movement, the Swiss phalanxes rolled downhill.

The pikes soon overbore the infantry, the center giving way first, then

the Burgundian left. With absolute control, the victorious formations

were faced to their left, where the halberd-armed troops of Uri, Schwyz,

and Unterwalden were hard pressed to withstand the cavalry charges

of

the enemy, as the Burgundian lances outreached the infantrymen’s pole

arms. The Berners and their associates took the horsemen in the flank

and rear. To the Burgundians credit, they made an attempt to break

into

the pike formations before fleeing the field as their footmen had done

before them. While von Erlach had given the Confederates the advantage

of terrain, it was discipline and hard fighting, coupled with the

tactic of employing three phalanxes, which won the day. If adversaries

of the Swiss and proponents of cavalry over infantry thought that

perhaps it was a fluke combination of terrain advantage and horsemen

who fought without bravery, another Courtrai, they would find out

otherwise soon enough.

Sempach was an interesting experiment in fighting against the

Swiss by use of similar tactics. Leopold III, Duke of Austria, invaded

Confederate territory and came upon the Vorhut of Lucerners which

was some distance from the balance of the army. He dismounted his armored

cavalry and took the initiative by attacking and nearly defeating

the Swiss phalanx, using his lance as pikes. As the crucial moment,

the

Gewaltshaufen and Nachhut arrived to relieve the first formation, so

Leopold attempted to bring his second “battle” into play, also dismounted.

The two Swiss divisions meanwhile formed a Kiel (wedge) —

a phalanx of extra depth to break an exceptionally strong enemy line

or

unit. The Austrian advance was ragged and disordered, for they were

not trained infantry, and before they could come up the Swiss broke

the

first Austrian “battle” and impacted upon the disorganized second.

The

third group, seeing that the day was lost, turned and rode off, leaving

their fellows, and the Duke, to their fate. Obviously, the armor and

weapons of the feudal cavalry allowed them to successfully contend

with the Swiss halberdiers, but a cavalry force is seldom so well trained

as

to be able to perform well as infantry, “hobilars” in medieval terms.

Similarly, armored footmen would be hopelessly outmaneuvered by the

Swiss. However if such a force could be sufficiently trained and disciplined

the results would be distinctly unfavorable to the Swiss. The

leaders of the Confederates realized the danger and ordered that more

pikes be included in all future levies.

The Confederates were left more-or-less unmolested for over 30

years, and during this time they extended their territory by diplomatic

maneuvers. These gains inspired neighbors to attempt to rectify matters

and perhaps gain Switzerland in the bargain. Confederate expansion

southwards caused the Duchy of Milan to declare war, and in 1422 the

Battle of Arbedo was fought. The wily condottiere Francesco Bussone

(Carmagnola) with a force of 6,000 gendarmes (heavy cavalry)

faced a

Swiss force of only 4,000. The latter drew up into a single block,

and the

initial Milanese attack was repulsed bloodily and with ease. Carmagnola

then dismounted his troops, and the heavily armored men formed a

phalanx similar to that of their adversaries and fell to with lance,

sword,

and like arms pitted against the Swiss force of halberdiers. Better

armor

and longer weapon so mauled the confederates that one of the chief

leaders of the Swiss indicated that he was prepared to surrender, but

the

Milanese refused to offer quarter to people who would not give it to

others, so the fight continued. The Swiss were near the breaking point

when the Milanese saw a body of Swiss troops cresting a nearby rise,

and

Carmagnola drew his men back to await further developments. The unit

was but 600 men, a body of foragers returning to the main party, but

their timely appearance allowed the battered Confederates to withdraw

from the battle. Only one-third of the entire force at Arbedo (troops

from

the Forest Cantons, Lucern, and Zug) did not bear halberds. Of that

third, only about half were pikemen, the balance crossbowmen. The

Milanese lost more than the Swiss, but proportionately the battle was

a

disaster for the Conferedates. For the immediate time they hastily

drew

up instructions for the relegation of the halberd to the interior of

the

phalanx for use only when the unit was locked in melee. Some 50 years

in the future they would settle matters with Milan.

At Saint Jacob-en Birs a small body of 600 or so pikemen crossed

the river to attack an army of 15,000 invading French. This small

phalanx broke the enemy line, but were then surrounded. By dint of

repeated cavalry charges and showers of crossbow quarrels, the Swiss

finally died to a man, but they refused to surrender, and the French

lost

some 2,000 men in the fight. Thereafter, the Dauphine turned back to

France, giving up his plans of conquest in Switzerland.

Hericourt, Grandson, Morat, and Nancy were the four major battles

which caused Charles, Duke of Burgundy, to be named the Rash

rather than the Bold. The Swiss used their normal echelon of three

divisions

at Hericourt and soundly defeated the Burgundian force opposing

them. At Grandson, the Vorhut again advanced too quickly, and the

men of Bern, Basel, Schwyz, and Fribourg were set upon by the finest

cavalry in Charles’ army — which was so easily repulsed that the column

began to move down slope to test their strength against the rest of

the

Burgundians there! Charles thought to perform another Cannae, and

he sent orders to his center to pull back so as to form a pocket into

which

the advancing Swiss would rush. The Burgundian army was composed

of their own knights and foot and in addition had contingents of English

longbowmen, German arquibusiers, Italian stradiot (light) cavalry,

and

Flemish pikemen. As the Vorhut neared contact, however, the other

two divisions finally appeared upon the shoulders of Mount Aubert.

The

Burgundian forces panicked and fled, mistaking the retirement of the

center group for a retreat. Lacking any cohesion, Charles’ army was

beaten without a real fight. At Morat, the Swiss managed to march

across the Burgundian front because Charles failed to put out any

scouts, and the results were defeat in detail and slaughter of the

Burgundians.

At Nancy, the final battle, the Swiss again showed great tactical

skill, fixing the attention of the Burgundians with the Gewaltshaufen

and

Nachhut while the Vorhut moved through a woods to come upon the

Burgundian flank; they were again defeated in great detail and Charles

was cut down by a blow from a halberd while trying to rally his troops.

A greatly inferior force of Swiss broke the Milanese army invading

the Ticino Valley at Giornico, avenging Arbedo and causing their

already high repute to soar. The battles against the Swabians at

Frastenz, Calven, and Dornach were typical of Swiss bravery and determination

and lack of clever tactics. The straight onset of pikes typically

won each battle, and again the repute of the Swiss as the finest infantry

in the field was universally acclaimed. But there were many imitators

of

Swiss tactics — German landsknechte, French landsquenets, Italian

pikemen, Flemish pikemen — and these troops were hard to beat,

especially the Germans. Although the Swiss were never bested by landsknechte

on a fair field, they were certainly slaughtered by them at La

Bicocco, and each victory cost the Confederates dearly in lives. Furthermore,

tactics were improving, and artillery, the greatest foe of the mass

formation was coming into its own. Without adaptation, the Swiss were

doomed, and they refused to change, relying on the tried and true when

they were outmoded. This is not to say that the pikeman was finished

on

the battlefield, for that would be an obviously stupid assertion. Pikemen

were to play a part in battles for many decades to come, but such arms

could only survive in a balanced force of missile infantry, cavalry,

and

artillery as well. The Swiss still served as mercenary pikemen, but

never

after La Bicocca and Pavia V were they the dominant force in a battle.

The organizational structure of the Swiss certainly should have

enabled them to be tactically flexible. The divisions of a field force

could

be massed into a huge column, form a hollow, moving square, and

otherwise perform with perfect discipline in battle. The Swiss used

light

infantry with great effect, deploying them as skirmishers to both weaken

the enemy and draw musketry and artillery fire upon themselves while

the phalanx columns marched to impact unmolested. The three

echeloned divisions had the advantages of multiple impact, flank protection,

and reserve all rolled into one. Left, center, right, or any combination

could be refused until the Swiss chose. Of course, the Confederates

had no cavalry, to speak of, and this was a drawback, but not a

serious one until Spanish sword and buckler infantry arrived on the

scene. The early victories of the pike formation over virtually all

opponents

undoubtedly built an illusion of invincibility in the minds of the

Swiss — common soldier and captain alike — for they triumphed with

such relative ease. Had another von Erlach arisen perhaps there could

have been a redemption of the Swiss military reputation, but it was

not to

be. Besides, the free-thinking and highly independent mountaineers

would probably have paid no attention in any event. So later battles

consisted

of simply bringing the pike column before the enemy, “aiming” it

at the desired spot, and sending it foreward to whatever fate awaited,

trusting to the fighting ability and stubborness of the soldiery to

overcome

everything in the way. Thinking commanders eventually

discovered ways to defeat such tactics (or lack thereof). The era of

the

Swiss pikeman came to a close at the dawn of the Renaissance, although

it took the terrible results of battles such as Marignano to finally

prove it to

all concerned.

Bibliography

Those interested in further reading are recommended to:

A DICTIONARY OF BATTLES. David Eggenberger

HISTORY OF THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES. 2 vols.

C.W.C. Oman

HISTORY OF THE ART OF WAR IN THE XVI CENTURY.

C.W.C. Oman

THE ART OF WAR. Niccolo Machiavelli

ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA. Eleventh Edition, vol. 26

Those wishing to experiment on the table top with miniatures to

recreate the Swiss battles are recommended to:

CHAINMAIL. Gary Gygax & Jeff Perrer

These medieval miniatures rules were carefully researched to

assure close simulation of the type of battles common to the Swiss

pikemen.