| Monsters | - | Dragon 106 | - | Dragon |

The hearthfire flickered in the tavern

known as The Leaning Post. The evening

was old, and the few tipplers left in the

taproom were crouched close around the

fire. Tongues were wagging with tales of

fell

keeps and grim adventures, and monsters

most strange. Old Urvan, a grizzled warrior

of scars and reputation most grim, rubbed

his bald pate and disagreed with a younger

man.

?Nay,? he rumbled, wagging a cold grey

eye, ?men die like cattle, for all their

armor;

I?ve fought a dozen, on horseback,

and slain them all, and me a lone man with

but my fists. But the woman-monster, the

medusa, the maiden who turns ye to stone,

is far the worse.?

From his dark corner, Elminster coughed.

?Oh? Think ye so?? he said casually. Everyone

fell silent at the sage?s words. He

spoke seldom, but his tales were not soon

forgotten. Old Urvan fixed the sage with

a

colder grey eye and emitted a grunt that

urged Elminster to speak.

?The medusa

is a fearsome thing, true,?

Elminster said slowly, looking around the

firelit circle of faces. ?But as bad or

worse is

the male, the stealer-through-stone, the

maedar. Medusae, ye see, have mates. An?

they?re by far the deadlier sex. . . .?

Elminster then unburdened himself of the

tale of Ilguld the illusionist and the

Walking

Stone of Yarech. It is a long tale, full

of

mimes and bawdy jests and local jokes,

and

unless one is the raconteur Elminster is,

?tis

better to paraphrase, thus:

Ilguld was an adventurer, the youngest

and least powerful of a proud and reckless

band who rode out of Waterdeep often,

combing the caverns of the wild North.

On

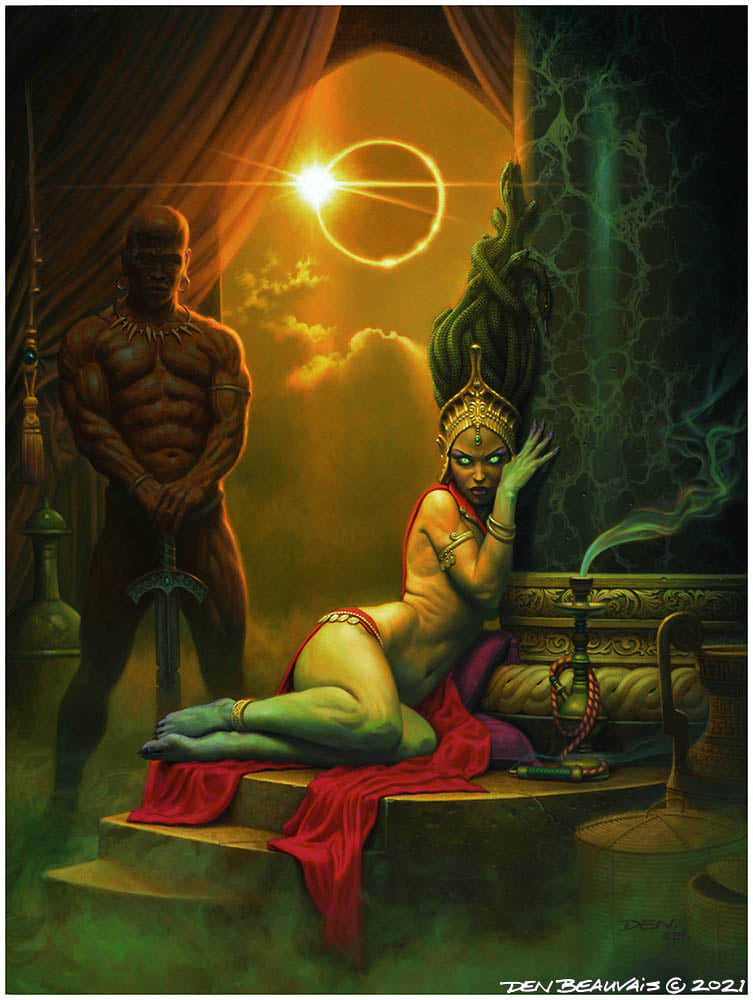

one jaunt, the group met a medusa, whose

gaze turned two brawny warriors to unmoving

stone. The survivors withdrew hastily

and thought of a plan. Ilguld had with

him

a small mirror, and this he tied across

his

eyes so that, peering down, he could see

only the ground before his toes. He covered

himself in his storm cloak, the cowl thrown

forward to conceal his face.

Thus prepared, Ilguld advanced into the

monster?s lair, shuffling like an old man

and

leaning on a staff. The medusa rushed him

to bite and slay. As he tried to fend her

off

with his staff, she tore open his cowl

? and,

gazing into the mirror, turned herself

to

stone while she still clutched him.1

Ilguld tugged himself free of the stony

grasp, ran from the lair, and called his

comrades out of hiding. They rushed forward

heedlessly to seek the medusa?s treasure,

waving aside Ilguld?s stammered

warnings, and were soon deep within the

maze of small caverns that made up the

medusa?s lair. Ilguld followed more cautiously,

and was scared badly when he saw

his comrades at the other end of a long

cavern ? coming back toward him as fast

as they could run with their bags of coins

and coffers of gems. The illusionist noticed

immediately that two of the band were

missing. As he watched, a part of the wall

seemed to move, reaching out to fell the

rearmost adventurer. At that, Ilguld cast

a

spell of invisibility on himself and fled

until

he was just inside the entrance to the

lair.

Seconds later he again heard the weaponclanking

and curses of his comrades. They

had dropped their treasure and were running

hard. The men, now without two more

of their number, burst past him and out

of

the cave. Ilguld remained frozen as he

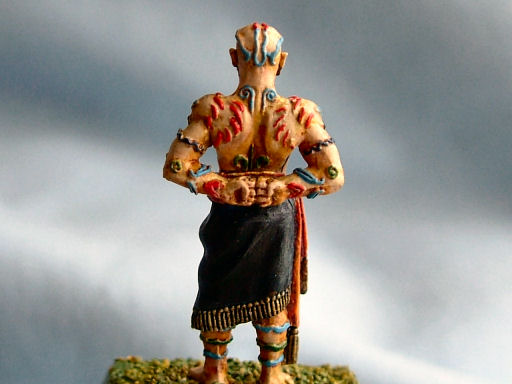

beheld what had chased them out ? a

muscular, bald-headed man clad only in

breeches, who came behind the group at

a

fast trot2.

Ilguld dared to leave the cave entrance

after this strange man passed, taking care

not to stumble or make undue noise. He

turned in the direction his friends had

gone,

and just ahead he saw them ? statues, all,

frozen forever in the midst of their flight.

Beyond the statues stood the medusa, stone

no more, her arms raised in triumph.3

As he watched the bald man approach the

medusa, Ilguld realized that she must have

somehow been restored to life and had left

the lair by another route so as to lie

in wait

for the intruders to exit. The medusa and

the man embraced, and she spoke to him

in

loving tones.4 Ilguld was amazed again

by

what happened next. He saw the man shatter

the stone form of his fellow mage and

then touch some of the fragments, which

turned from stone rubble to bloody flesh.

The bald man and his mate, the medusa,

sat down to eat as Ilguld tore his gaze

away

from the scene and stole away as softly

as he

could.

?A likely story,? Urvan scoffed. ?One

man, weaponless, defeating an entire

band??

?Why, Urvan,? Elminster replied mildly,

lifting his tankard, ?I hear from your

own

lips that such a feat ? defeating a dozen

armed men, and their horses too ? is easy,

if one has but the use of both fists. Is

it then

not so??

?Phauugh,? Urvan replied eloquently.

-

1. The gaze of a medusa can turn itself

or

any other medusa to stone. Such petrification

is permanent unless reversed by spell or

special ability (see note 3 below).

2. Maedar are the male counterparts of

the medusae. (Singular and plural forms

of

?maedar? are the same; the name can be

used to refer to both genders collectively,

or

to the male alone. The latter usage is

employed

in this text.) The maedar are far

rarer and more reclusive than their mates,

and are seldom seen. Many men do not

even know, or believe, that they exist.

They

dwell in the depths of caverns, guarding

the

pair?s hoard of treasure (and food) while

their mates hunt.

Maedar appear as bald-headed (in fact,

completely hairless) muscular human males.

In all statistics they are identical to

medusae,

except that they have two attacks per

round, doing 2-8 points of damage with

each blow of their mighty fists. Maedar

cannot petrify other creatures and are

themselves

immune to petrification and paralyzation

(including related magics such as slow

and hold spells) from any source whatsoever,

although they can be confined by

webs, forcecages, and the like.

3. Maedar have the ability to turn stone

to flesh by touch, once every three turns.

Thus, one can free a medusa who has gazetrapped

herself to stone ? or, by smashing

petrified prey to rubble and then turning

it

to stone, gain an easy meal for himself

and

his mate from a creature petrified earlier

by

the medusa. Like medusae, maedar can see

into the Astral

Plane and the Ethereal

Plane, and they can use their stone to

flesh

ability into those planes as well.

Maedar possess the ability to pass

through stone as xorn and xaren do, at

normal movement rate. A maedar requires

one round of concentration to adjust his

molecular structure before entering rock

and after leaving it again; no other activity

may be undertaken during this round. If

struck by a phase door spell while passing

through stone, a maedar is killed. If a

mated maedar and medusa are confronted

by a stronger creature in their lair, the

male

will abandon the female to her fate without

hesitation, escaping through the rock walls

of the cavern. However, a maedar will

never neglect to unpetrify a medusa when

it

is safe to do so.

The treasure of a medusa and maedar is

usually concealed (behind loose stones,

in

crevices, etc.) in addition to being guarded

by the maedar. The males monitor the

treasure continuously and frequently move

it from place to place within the lair,

particularly

to discourage thievery by other creatures

able to pass through stone. Males and

females alike will flee from strong attackers,

abandoning whatever treasure they cannot

carry, rather than defend a hoard to the

death. The treasure hoard of a medusa and

maedar will almost always contain a selection

of feminine garb that doubles as the

medusa?s wardrobe.

4. All maedar and medusae speak and

understand the language of lawful evil,

the

common tongue, and any other languages

spoken often by creatures in the vicinity.

Details of the courtship of a mated pair

are

unknown, but they do pair for life (one

choosing another partner only if a mate

is

slain), and live and hunt together at all

times. The female produces 1-3 live young

every 10 years or so. Young have the same

abilities as their parents, but no physical

attacks and only 1-2 HD. (A young female

can petrify, and a young male can pass

through stone and turn stone to flesh;

however,

the asplike, poisonous ?hair? growth

of a medusa develops only in maturity,

and

young maedar lack the strength for damaging

blows.) Offspring gradually gain hit dice

as they approach maturity and adulthood,

a

process that typically takes four or five

years. When they reach maturity and gain

the ability to physically attack, the young

are roughly encouraged to strike out on

their own; no more than one adult medusa

and one adult maedar will ever be found

in

the same lair. If a medusa is slain but

her

mate survives, the male will search tirelessly

for the killer(s) to take revenge, sometimes

pursuing such quarry for years. A maedar

can track as a ranger does, but this does

not

include the ability to follow the trail

of a

creature that has passed through stone.

All

maedar and medusae are immune to the

poison of (their own and other) medusa

hair

growths.

Medusae and maedar respect, but do not

worship, Skoraeus

the Living Rock (see

Legends & Lore, Nonhuman Deities),

and

have a like attitude toward lawful evil

deities

and creatures. They will cooperate with

lawful evil creatures such as orcs, kobolds,

or even devils, for reward or security

or

(rarely) under duress. If forced to aid

or

serve another, they will always seek revenge.

Meader and medusae cannot be

trusted by other creature except of their

ilk.

Occasionally they will bargain with, or

purchase information or services with,

their

treasure.

THE FORUM

In the article on the medusa

and the maedar in

issue #106, I detected an ambiguity which

I think

needs some clarification. It described

the maedar

converting stone to flesh from adventurers

that

the medusa had petrified, and the medusa

and

maedar using this as a source of food.

Yet the

article also stated that the medusa would

leave the

lair to hunt. If the maedar had the ability

to

convert pure stone to true flesh, what

need would

there be for a medusa to hunt, as an ample

food

supply could be obtained directly from

rocks?

A rational explanation in my opinion would

be

that the petrification power of the medusa

does

not turn flesh into true stone, but rather

into a

substance as hard as stone ? possibly by

a process

of solidification of the fluids normally

present

in living organic creatures. For example,

water in

the liquid form is very soft and flexible,

whereas

water in the solid form (ice) is very rigid

and

hard. Also, all living organic creatures

have

certain species-specific essential nutrient

requirements

(e.g., vitamins and minerals). Therefore,

although the maedar could convert true

stone into

a substance as soft and flexible as flesh,

it would

not be true flesh because it would not

have the

chemical composition of true flesh. Only

“stone”

which had originally been true flesh would

contain

those chemical nutrients which the medusa

and maedar would need for adequate nutrition.

J. M. Talent

Denton, Tex.

(Dragon

#108)