The ecology of the ochre jelly

by Ed Greenwood

?Old favourites? time, is it?? Elminster

asked, draining his cocoa and reaching for

his pipe simultaneously with practiced ease.

?I know that ye folks that play at the sort o?

things that happen for real in the Realms

are overly fond of pitting yer characters

against witless giant amoebas! Just about

their style, eh??

I regarded him over the uplifted bottom

of my mug. ?Witless giant amoebas?? I

asked, with the proper amount of deference

in my tone.

?Ochre jellies, ye dolt!? Elminster shot

back, expelling puffs of green smoke like a

testy dragon. ?Ye just asked about ?em ?

don?t ye know anything to start with??

?They?re blobs, they ooze along looking

for food ? like adventurers ? and they?re

always hungry,? I offered. ?I hoped you?d

fill in the rest.?

? ?Course ye did! ?Course ye did!?

Elminster replied, drawing on his pipe.

?And,? he sighed (Ever see someone sigh

while drawing on a pipe? Spectacular!), ?I

suppose ? as usual ? ye?re right. Pay

attention, then ? and no questions,

mind, till the tale?s done.?

I did as I was told, and Elminster

related the tale of ?How Grymmar Held

the Pass?:

?Now, in the days when the Sea of Fallen

Stars was new to men, and the lands still

wild and unsettled, bands of lawless men

rose about scavenging and slaying and

pillaging. Kings were hard put to it to pay

and train fighting-men to guard themselves

to say nothing of their kingdoms. And whe

a king rode to war, it was likely to be with

another king, over some insult or spurned

daughter or an uncertain line on a map.

Kings did not spend time or men chasing

after a few brigands who would flee and

leave traps behind, or set an ambush, and

in the end melt away before searchers as

though they had never been ? until the

searchers turned their backs, of course.

?The King of Cormyr was one of these

monarchs, and a man with a problem. After

spending a hot summer fighting all across

his realm, from the Wyvernwater to

Eveningstar, he had few men indeed left to

call the Royal Host of Cormyr ? some

sixty-five stouthearts, to be exact. Then his

weary ears heard news of an incursion from

the east into Arabel, a merchant city too

precious to give up without a fight.

?This was bad enough in itself, but com-

pounding his plight were local cries rising in

Eveningstar about bandits on the roads

and a huge brigand army somewhere in the

mountains to the west. Nowadays, with the

great fortress of High Horn looming over

the west pass, such news would be of little

concern. But in these early days of Cor-

myr?s sovereignty, no such fortress existed

to impede the progress of enemies from the

west. Clearly, the king?s men could not be

in both places at once, and dividing the

force could mean failure for both halves.

But the king dared not disregard either

threat. He called his men together to give

them the facts of the matter and told them

to be ready to travel the following day.

?Later that evening the king called for

Grymmar, the oldest of his stalwarts, and

asked for the grizzled lieutenant?s counsel

on how to divide soldiery and supplies so as

to meet each threat. The king was surprised

to hear that Grymmar had formulated a

plan to deal with the brigands ? a plan for

which no soldiers would be needed, save

Grymmar himself and a couple of strong

men. The monarch gave his approval to the

plan and his blessing to Grymmar, supply-

ing him with documents that would enable

him to acquire the goods and services he

would need, and on the morrow the king

led his army eastward.

?Grymmar spent part of this first day

gathering supplies. With the king?s author-

ity to lend weight to his requests, he pro-

cured an unused stone coffin, placed within

it three grunting and squealing pigs, and

with the aid of his strong assistants loaded it

into a cart along with a barrel of pitch and

several torches. Then Grymmar and his

curious entourage set out ? not directly for

the pass, but on a northerly route to a place

not far from Eveningstar.

?Only days earlier, some of the king?s

men had cleaned out this place, an old

dwarf-delve that had served as a hiding

place for a group of bandits. A dozen ruffi-

ans there were in all, no trouble ? but

Grymmar and the others with him had all

taken a fright when, as they leaned on their

swords afterward in a deep and freshly

bloodied chamber, something moving and

shapeless and alive, ochre in color and

horribly hungry in motion, had oozed in

under the door.

? ?A flesh-eater! ? one of the warriors had

warned, and they all had backed away

hastily as the jellylike thing advanced. It

flowed over stone and corpse alike, and left

only bones and metal in its wake. The

soldiers circled toward the exit, rushed

through the doorway, slammed the portal,

and sealed the space between door and floor

with loose dirt.

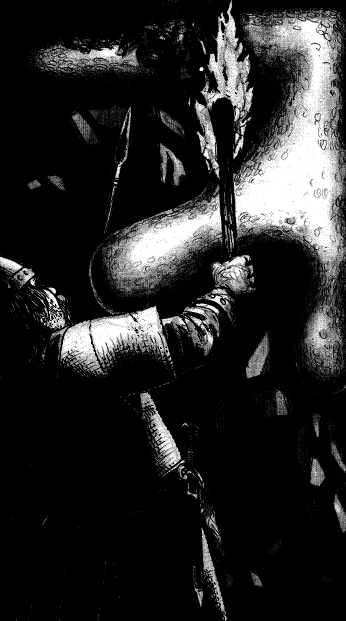

?Now Grymmar made a return visit to

the bandit hold, and with the help of his

companions transported the contents of the

cart down into the chamber where the flesh-

eater was last seen. The coffin was set out,

its lid awry, and the men sat nearby inside a

circle of pitch they had smeared on the

floor. Fairly soon the flesh-eater appeared,

attracted by their presence, flowing eerily

along a wall. Grymmar set the ring of pitch

aflame, and the jelly shrank away from the

men and went for the pigs in the coffin.

When the thing was entirely inside the

coffin, the men leapt forward, put the lid

back in place, and sealed the container with

more of the pitch. Then they carried the

coffin back to the cart. Grymmar and one of

his helpers headed directly for High Horn

Pass, and the other man veered toward the

druids? grove in the forest to the south and

east of the pass.

?By the time Grymmar reached the pass

at sunset of the following day, he could see

the bandits in the distance, approaching

from the other direction. He and his cohort

unloaded the coffin, storing it under a ledge

where it would not be detected in the dark-

ness, and watched from an elevated hiding

place as the brigands made camp in the pass

itself ? an expanse of land broad and flat

enough to house all of their tents at once,

although they had to keep rather close

quarters.

?Then the druids arrived in the dark of

night, responding to the summons of their

king as conveyed by Grymmar?s helper, and

it was time to put the last stage of the plan

into action. Grymmar crept back down to

the coffin, scraped away the pitch, and

loosened the lid. At the same time, the

druids began their enchantments. Massive,

threatening clouds formed in the sky above

the pass, and before too long the air was

rent with driving rain, booming thunder,

and crackling bolts of lightning. The ban-

dits were protected from the elements inside

their tents, and they slept unafraid, but

tent-cloth could not keep them safe from the

real danger.

?To this day, some folk still tell of how the

druids saved Eveningstar by bringing down

the awesome storm that decimated the

brigand army and forced the survivors to

turn back. But others know better, for they

have heard the real tale. The storm abated

after a time, and at first light the next

morning when Grymmar and the druids

looked down upon the bandits? campsite,

they saw scores of flesh-eaters ? born of the

lightning strikes ? and dozens of corpses,

many of them already nothing more than

skeletons. The few bandits fortunate enough

to escape death from the jellies now could

see the carnage that had been wrought

during the night, and they ran for their lives

back the way they had come. . . .

?. . . And that was how Grymmar held

the pass.?

At this point Elminster sat back and re-

ignited his pipe, satisfied with the way he

had told the story. I thanked him ? and

indeed it was a good tale ? and then set

about quizzing him as to the practical (to

adventurers) details of the ochre jelly.

Elminster related the following information,

much of it drawn from the Bestiary of

Hlammech the Naturalist:

An ochre jelly is amorphous in form,

having an outer elastic ?skin? or bag of

tough, translucent cells, ochre in color.

Inside the skin is a large mass of fluid ? the

main bulk of the creature. This fluid is

thick, soupy stuff ? stabbing an ochre jelly

won?t cause the stuff to drain away quickly,

like the way a wineskin loses its contents if

punctured; fluid will ooze from the wound

until excess skin cells (produced from the

cellulose the creature devours, and carried

around in little globules inside the fluid)

arrive to ?patch the leak.? In this fashion,

an ochre jelly can heal any wound it suffers

from an edged weapon within 5-12 rounds

(d8 + 4). A wound from a blunt weapon is

more traumatic, rupturing a greater num-

ber of skin cells and taking 11-20 (d10 + 10)

turns to close. In either case, the hit points

lost when the wound was suffered are re-

gained when it is healed.

Because of its construction, an ochre jelly

can squeeze through any crack large enough

to permit a thin ?wafer? of skin cells (both

sides) and internal fluids to pass ? about

an inch in width is required for an average-

sized jelly. The creature?s movement rate is

only 1? when it compresses itself to travel

through an opening smaller than the jelly?s

normal thickness. When at rest and under

normal conditions, an average-sized ochre

jelly is 3 to 6 inches thick and occupies a

surface area equivalent to a 6? -diameter

circle; however, the term ?at rest? is theo-

retical in this case, because an ochre jelly

never stops moving except to devour prey.

When it moves, it does so by extending one

or more pseudopods of skin and fluid, be-

coming elongated in the direction of move-

ment, and setting up a rippling motion that

enables it to ?slosh? forward by means of

inertia.

Ochre jellies can adhere readily to walls,

ceilings, glass, and so forth ? they do not

seem affected by water, wine, oil, grease,

and the like, and have never been observed

to slip ? but their grip on surfaces is not

strong enough to enable them to pull open

chests, armor, closed doors, etc., and they

can be readily scraped or shoved off of a

surface by a creature of at least average

strength.

The creatures are non-intelligent and

have no visual organs as we know them.

They can detect heat, vibrations, and the

scents of organic substances, and will move

in the direction from where these stimuli

come (in the order given; ochre jellies ap-

parently ?prefer? live humans or animals as

prey, but can ?smell? wood or plant

growth, or corpses, if no live creatures are

in the vicinity). They can sense the heat of a

torch flame at a range of 500 feet, and the

body heat of a living animal from 100 feet

away; their sensitivity to vibrations (such as

those caused by footsteps) or scents has a

range of at least 500 feet, and often much

farther depending on the severity of the

vibration or the intensity of the odor; for

instance, an ochre jelly can detect a troglo-

dyte, by its scent, from several hundred

yards away.

Ochre jellies will move mindlessly toward

any stimulus, but will not voluntarily come

into direct contact with any stimulus (such

as a flame) that can damage them. In the

absence of any detectable stimulus, an ochre

jelly will continue to flow in the direction it

is heading until forced to turn or double

back on its path because of an obstacle;

Grymmar and his companions were bound

to eventually encounter the ochre jelly in

the closed-off chamber, because the creature

had nowhere else to go.

When an ochre jelly comes into contact

with any consumable (i.e., living or once-

living) substance, a number of one-way

valves in the creature?s skin surface will

open, and globules of the corrosive digestive

fluid inside will be expelled onto the prey.

This fluid seems to be a sort of acid-based

enzyme which first eats away and then

breaks down (by chemical reaction) the flesh

or cellulose. The ochre jelly then reabsorbs

the digestive fluid at the same time that it

ingests the nutrients, through a set of simi-

lar one-way valves that work in the opposite

direction. These valves are very selective,

only letting in the fluids that the ochre jelly

?intends? to absorb; the creatures have

been encountered in coastal salt waters, and

in order to subsist in such an environment,

they must be able to prevent the taking in

the water with which they are surrounded.

As so often happens with the unique body

fluids of certain mysterious creatures, the

acid-enzyme secreted by an ochre jelly

becomes inert if the creature is killed or the

fluid is somehow prevented from being

reabsorbed by the body. This neutralization

of the fluid takes place immediately upon

the death of an ochre jelly, or if the creature

is forced to abandon partially consumed

prey (which is why a victim?s flesh does not

continue to ?dissolve? if the jelly is killed or

pushed off). Similarly, the skin of an ochre

jelly loses its distinctive properties after the

creature is killed and cannot be salvaged for

any useful purpose.

An ochre jelly can and will instinctively

flow over or around its prey, enveloping it

so as to retain contact if the target moves or

struggles. If the creature is attached to a

wall or a ceiling, it can send out pseudopods

to contact something edible that is below or

beside it. Once having made contact in this

fashion, the jelly can detach itself from the

wall or ceiling and flow onto the victim.

An ochre jelly can be damaged by cold-

or fire-based attacks. Severe cold (freezing

temperature or lower) of a lasting nature

will further impair the creature, slowing its

movement rate to 2? and adding 2-5 rounds

to the time required for it to heal a wound,

since its internal fluids cannot flow as freely

to reach the affected area. (Note that a cone

of cold spell, to name one example, is not

cold ?of a lasting nature,? since the spell?s

duration is instantaneous.) Any single fire-

based attack that does damage equal to at

least one-quarter of the creature's maxi-

mum hit points will cause a wound that

takes 16-25 (d10 + 15) rounds to heal, and

for 4-7 rounds following the attack the ochre

jelly will lose 3 hit points per round as fluid

continues to leak from the wound. Fire

damage of less severity will take 11-20

rounds to heal, the same as for a blow with

a blunt weapon.

The sudden application of intense electri-

cal energy (such as a lightning bolt or magi-

cal or natural origin) does not damage an

ochre jelly; instead, this serves to increase

the creature?s metabolism and cause it to

divide immediately (within the round fol-

lowing the electrical contact) into a number

of smaller jellies, each identical to the origi-

nal creature in all respects except for size

and damage; they are capable of doing 2-6

(d4 + d2) points of damage per attack. The

number of ?offspring? created is usually

(75%) 2-4, but occasionally as many as 5-8

are produced. These smaller jellies will

grow into normal-sized creatures (doing the

usual 3-12 points of damage) within 1-3

months after the split occurred.

In rare instances, an ochre jelly will split

?voluntarily? into two equal-sized creatures

(each doing normal damage), but only

when the original creature is of huge size.

Ochre jellies grow slightly every time they

feed, but do not shrink when they go with-

out food ? and they can survive for several

weeks on little or no nourishment. No ex-

ample is known of an ochre jelly that died of

?old age?; perhaps they do not age (as we

understand the term), or perhaps they

decompose quickly when they die in this

manner, thus leaving no evidence of their

passing.

An ochre jelly cannot be poisoned or

intoxicated or otherwise adversely affected

by attacks with purely fluids (including acid

but not including flaming oil). It will absorb

all such fluids, ?walling? them into globules

surrounded by excess skin cells, suspending

them within its internal body fluid, and

holding them harmlessly until it is not feed-

ing on prey or involved in combat, where-

upon it will expel them through the same

openings that release its digestive fluid. A

physical attack upon a jelly that ruptures a

globule of this stored fluid may cause its

contents to squirt out at the attacker.

Astute students of biology will note that

ochre jellies are not precisely ?amoebas? as

we know them ? but when I mentioned

this to Elminster, he merely fixed me with a

cold eye and grunted, ?Hah! And what do

your scientists in this world know of any-

thing?? And that is all I learned from him

about the ochre jelly.