| Dragon magazine | - | Monster Manual III | - | Dragon #83 |

From an address by the naturalist Elm-

daerle to the assembled Guild of Naturalists

in Arabel:

“. . . Understandably, little research has

disgusting and dangerous creature, the

been done on the life and habits of that

stirge. I have endeavored to learn what

I

can of them, and have, as you can see,

brought along a specimen.

"No, no, it's quite dead. . . . The

stirge, as we all know, subsists entirely

on a

diet of blood, and will attack all warm-blooded

mammals, although it seems to

prefer man. Quite often, stirge swarms

follow herds of domestic or nomadic

animals -- cattle, caribou, and sheep being

most often afflicted; and where such herds

are, one should always expect to meet,

and

be prepared for, these little fellows.

Caravans,

traveling pilgrims, and even armed war-bands

have been harried through wilderness

areas by large flights of stirges;

we've all heard the gruesome stories of

drained, white victims and a few lucky,

narrow escapes. I've studied these creatures

for some time, to get at the truth -- and

the

tales and legends, I fear, are not far

wrong.

“In flight, the stirge is highly maneuver-

able(1), and groups of

them are capable of

cooperative unison attacks and mid-air

actions. As you can see, it is really little

more than an expandable blood-bag with

wings, eyes, and claws — for clinging onto

prey — and a long, hollow needle-beak or

proboscis, admirably suited for drawing

blood. This specimen appears to be of about

average size, measuring just under one

foot

from top of head to tip of tail, and with

a

wingspan of just less than three feet.

The

wings may look unusually large, but if

they

were smaller, the stirge would not be able

to

maneuver as well as it does when its body

cavity is filled with blood.

“The proboscis, properly treated, can

serve as a sharp but brittle stabbing

weapon, much favored, I am told, by gob-

lins and similar unpleasant creatures.

When

the stirge is alive, the proboscis contains

at

its tip a supply of clear liquid, produced

in

the stirge’s body and steadily replenished;

this is an anti-coagulant, which mixes

with

a victim’s blood to keep it from clotting

in

the proboscis or in the stomach where it

ends up. The stirge, because of its diet,

can

transmit diseases —malaria, for instance

—

from one victim to the next. (2)

“Ingested blood passes straight into the

stomach. This serves as a storage bag which

the creature always tries to keep at least

partially full. From this reservoir the

crea-

ture draws small quantities into lesser

cavi-

ties located just beneath its backbone.

There its body processes convert blood

sugar into body energy, and ingested blood

into plasma balanced for its own bodily

use,

so that it can replace its own lost blood

and

hasten its recovery from wounds. (3)

“The interior of its wings is interlaced

with thin-walled blood vessels. By flapping

its wings, the creature fans air over these

surfaces, and thus cools its body when

in

hot sun or volcanic steam. Much of the

tissues of the stirge are liable to be

tainted

with disease, but the knots of muscle here

and here, just behind the head and atop

the

spine, at the bases of the wings, are humanly

edible. I would have liked to bring a

prepared, sample meal with me tonight,

but

I was uinable to procure more fresh stirges

-- and

once a stirge's legs have stiffened after

death, no part of its body is safe to eat.

“The creature’s claws are not strong

enough to be effective weapons for the

beast, but they are firmly embedded in

its

legs and at the midpoint of the leading

edge

of its wings, and they enable the creature

to

maintain; tenacious hold once it has attached

itself to its prey. The claws serve

some cloth-makers and workers for carding

wool, brushing away hairs and garments,

and so on. They are not strong enough for

the fanciful uses attributed to them in

the

tales of thieves -- they are far too brittle

and small to serve as grappling hooks for

climbing-lines.(4)

"Stirges swarm to attack prey, which is

why they are so feared -- one can be a

formidable foe, but a large group can be

deadly to even well-defended creatures.

Stirges usually lair in forests, disused

castles,

or caverns, and may incidentally possess

treasure from victims who have fallen

to them therein, or from hoards laid down

before their arrival, but they are not

intelligent

enough ot value, or bargain with,

treasure as we know it. A ranger of my

acquaintance tells me that stirges in deep

woods like to drive prey into tangled ravines,

so that the victims cannot escape

readily, or find steady footing, room,

and

balance to defend themselves properly --

and any treasure carried by these unfortunates

may well be found among their bones

at the bottoms of these ravines.

"Although a thirsty swarm of stirges may

seem endless when they're all swooping

down at you, typically only three to thirty

nest together in a colony, from which they

fly out in all directions to find food,

usually

in groups of three. By means of wagging

their probosci, stirges can communicate

that

food or a dangerous enemy has been found,

its direction, size or strength, and a

degree

of excitement or urgency regarding the

desired reaction of the whole swarm. If

a

flight of three sitrges finds prey, they

will

circle to observe it, and then two will

harry,

chase, or if it is strong merely fly along

observing it, while the thrid stirge flies

for

home. Its message will spread via all the

stirges it meets, and to all who call in

home

at the nest, and they will gather in a

group

to seek out the prey and kill it. Small

prey is

merely attacked by the hunting threesome

for their own gain, and they gives its

location

only later, if blood yet remains for their

fellows. (5)

“Winter cold does not seem to affect

stirges in any way, and they breed freely

throughout the year. They reproduce by

live

birth, in litters of one to three young,

with a

gestation period of six months. Males and

females are outwardly identical in size

and

appearance to our eyes. The tiny young

cannot fly properly, but only glide, and

are

carried on the mother's back for up to

four

months, until their blood-drinking from

prey (6) provides sufficient

nourishment for

them to grow to about half of adult size.

Then they can maneuver on their own, and

in another three months at most they reach

full adult size.

"I suppose that most of you have never

seen a young stirge, and I regret that

I

could not procure one to bring as a specimen.

The adults, however, you all should

know: pests feared by man and beast alike.

My colleagues Ainsbrith and Bremaerel of

Westgate are experimenting with poisoning

stirges, but so far report limited success.

Just as they are apparently immune to the

diseases they transmit, so are they unaf-

fected by the same poisons that harm us;

the creatures seem both adaptable and of

rugged constitution.

“And that, fellow naturalists, is a brief

look at the stirge. As more information

becomes available, I will share it with

the

group, and I will expect each of you to

do

the same.”

-

1. Stirges are flight class

A; if their wings

are damaged and/or they are fully bloated

with blood, and/or they have only 1 or

2 hit

points, they may be reduced to Flight Class

B or C and 16” or 12” aerial movement

rate, at the DM’s option. A mother with

young on her back (see text and note 6

below) is penalized even further, dropping

down one more flight class and another

4”

in movement rate, compared to what she

would be if she were not so encumbered.

2. Diseases contracted

from stirges will

almost always affect the “blood/blood-

forming organs”of the body (see DMG),

and be of the acute type. There is a 5%

chance for any adult stirge to transmit

a

disease to its victim on a successful hit.

3. Stirges can always regenerate

lost body

parts (over a period of 1-3 months) or

heal

even the most severe wounds (replacing

up

to 4 lost hit points every 24 hours), so

long

as their heads and spines remain relatively

undamaged, and food — i.e., fresh blood

— is plentiful.

4. Stirge claws resemble

the better types

of fish-hooks, in that they are both hooked

and barbed, curving to a point, which has

a

side-fin or point projecting backward from

its tip toward its shaft, in the same way

that

the edges of an arrowhead form two points

facing back toward the flight-feathers.

In a

live (un-stiffened) stirge, these barbs

are not

rigid, but can be retracted into the claw

by

means of strong cartilage-and-muscle link-

ages —thus, a stirge can hook itself into

a

victim through gaps in metal armor or by

simply piercing leather or lighter clothing,

so that it cannot be torn free except by

also

tearing away parts of its victim’s flesh

(1-2

points of damage per claw torn out, 4 claws

per stirge). In determining whether or

not a

stirge’s attack is successful, consider

a

missed “to hit” roll as indicating that

the

creature’s claws failed to latch on to

the

intended victim or victim’s clothing/armor.

If a stirge hits successfully, it has grabbed

on

with its claws and struck with its proboscis

in the same round; generally, a stirge’s

proboscis can strike into or through any

surface on a victim that its claws can

attach

to. Immediately after death, a stirge’s

mus-

cles relax, and it ceases both to drain

fur-

ther blood and to hold its barbs in — but

if

it is not removed from its victim within

4-6

turns, and is allowed to stiffen while

at-

tached, the barbs will have been extended

again as the stirge’s muscles convulse,

and

the body of the stirge will then have to

be

torn free of its victim, doing damage as

specified above. If it is attached to armor,

but not flesh, then the creature will be

easily

shaken or pulled loose by normal movement

when its muscles are relaxed.

5. As many as six stirges

can comfortably

(for the stirges, that is) attach themselves

to

the body of one man or other M-sized crea-

ture at the same time. Sometimes more

than six will do so, but usually only if

the

entire swarm is very thirsty, if the victim

is

a solitary creature, and if the victim

has

enough blood (i.e., hit points) so that

each

of the attackers can drain at least a little

blood. A charitable DM might rule that

each stirge after the third one attacking

a

single target does so at a cumulative -1

“to

hit” (-2 for the fifth, -3 for the sixth,

etc.),

because the target is, in effect, smaller

since

other stirges are already attached.

Stirges will attack the trunk of a victim’s

body in preference to the extremities,

since

the target area is larger, and those who

sink

their claws into a victim’s back will be

virtu-

ally immune to counterattack by the victim

himself. A companion can try to attack

the

stirges on a victim’s body, but if he misses

such an attack and rolls 4 or more under

the

number needed “to hit,” he hits the victim

instead of the stirge, and the weapon strike

will do half normal damage (round down)

to

the victim. The first successful attack

by a

stirge will be upon a victim’s back 66%

of

the time (4 in 6 chance), or else on the

front

of the torso. If the first attack hits

the front,

the second successful attack will always

be

on the back. After that, other stirges

will

attach themselves to the extremities —

but

must always hit the victim’s original armor

class (not AC 10, even if the arm or leg

being hit is unprotected). This “hit loca-

tion” determination is useful in knowing

whether a stirge’s claws are embedded in

armor or flesh.

A stirge filled with its quota of blood

can

subsist on that nourishment for as long

as

72 hours, and can go another 24 hours

without food after that before starving

to

death. However, stirges will instinctively

seek out new prey starting 36 hours after

their last “full meal,” at which time they

will have digested half of their full capacity.

6. Although a litter of

young stirges.

(stirgelings) can number as many as three,

a

mother can only carry two offspring on

her

back while they mature. The other one

must survive on its own, or perish; other

stirges will not transport the young in

place

of the mother. For every eight stirges

en-

countered in a single group, whether in

their lair or otherwise, one of those crea-

tures will be a mother bearing 1 or 2 young

on her back. When a mother carrying

stirgelings scores a hit on prey, the young

on

her back can begin attacking on the round

following her initial hit. Attacks from

young

are at -2 “to hit,” they do 1 point of

initial

damage from the proboscis, and drain 1-2

hit points of blood per round on following

rounds, becoming sated at 6 hit points’

worth. The mother must be detached

(killed) to stop the young from draining.

If

she drains her full quota of blood, she

will

remove her proboscis but remain attached

to the victim until she feels her young

also

pull free, signaling that they have also

drunk their fill. Stirgelings can easily

be

torn free from their mother’s back, and

typically have only 1-4 hit points. Stirges

who fall from their mother’s back without

being slain will die unless they can find

food

(usually by crawling into burrows to attack

young woodland animals).

OUT ON A LIMB

-

Right and wrong

-

Dear Dragon,

-

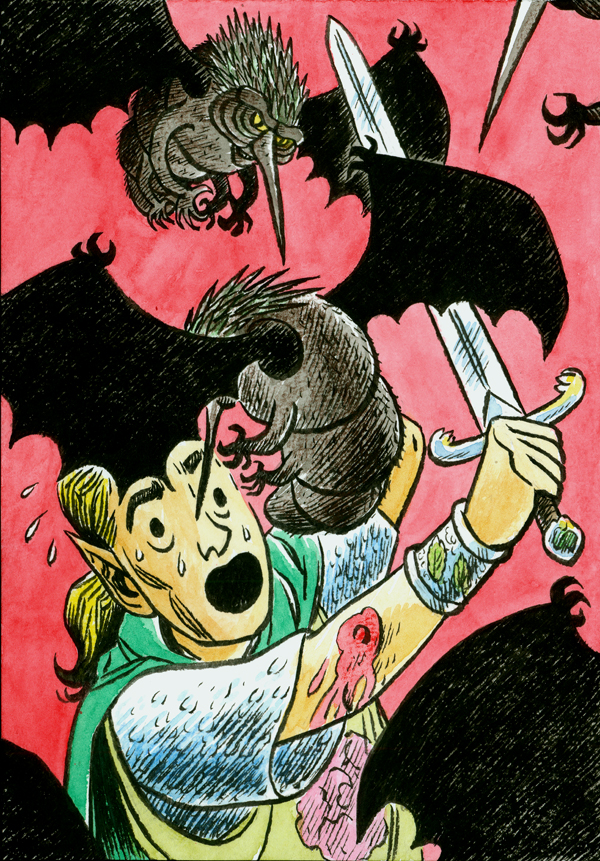

In the article on the stirge (issue #83), I

noticed

some differences between the description in the

magazine and in the Monster Manual. The

manual says "The feathers of a stirge

are rusty

red to red brown," and it also says, "The dangling

proboscis of a stirge is pink at the tip,

fading to gray at the base." The picture in the

magazine showed the wings to have no feathers

and the proboscis is shown as a straight beak.

Mike Peters

Curwensville, Pa.

(Dragon #87)

Sometimes, the authors of our ecology articles

draw conclusions that are different from assertions

in the Monster Manual, but

we don't worry

about the differences very much as long as

they're logically explained. Our illustration of the

stirge depicted a bat-like creature with feathers on

the crest of its head, but not on the wings. This

goes along with the passage in the article about

how the stirge cools its body by flapping its

wings. If the blood vessels in the wings were

insulated from the surrounding air by a layer of

feathers, this cooling process would not work as

described. A stirge's proboscis can be "dangling"

(pointing downward) and rigid at the same time,

which is how we tried to portray it -- and it must

be stiff, or the creature wouldn't be able to penetrate

the skin of its victims.

-- KM

(Dragon #87)

| Dragon magazine | - | Monster Manual III | - | Dragon #83 |