THE GREEN MAGICIAN

by L. Sprague de Camp

-

-

n that suspended

n that suspended

moment when the

gray mists began to whirl around them, Harold

Shea realized that, although the pattern was perfectly

clear, the details often didn’t work out right.

It was all very well to realize that, as Doc Chalmers

once said, “The world we live in is composed

of impressions received through the senses, and if

the senses can be attuned to receive a different series

of impressions, we should infallibly find ourselves

living in another of the infinite number of possible

worlds.” It was a scientific and personal triumph to

have proved that, by the use of the sorites of symbolic

logic, the gap to one of those possible worlds

could be bridged.

The trouble was what happened after you got

there. It amounted to living by one’s wits; for, once

the jump across space-time had been made, and you

were in the new environment, the conditions of the

surroundings had to be accepted completely. It was

no good trying to fire a revolver or scratch a match

or light a flashlight in the world of Norse myth;

these things did not form part of the surrounding

mental pattern, and remained obstinately inert

masses of useless material. On the other hand,

magic . . .

The mist thickened and whirled. Shea felt the pull

of Belphebe’s hand, clutching his desperately as

though something were trying to pull her in the other

direction.

Another jerk at Shea’s hand reminded him that

they might not even wind up in the same place, given

that their various mental backgrounds would spread

the influence of the generalized spells across different

space-time patterns. “Hold on!” he cried,

and clutched Belphebe’s hand tighter still

Shea felt earth under his feet and something hitting

him on the head. He realized that he was standing in

pouring rain, coming down vertically and with such

intensity that he could not see more than a few yards

in any direction. His first glance was toward Belphebe;

she swung herself into his arms and they

kissed damply.

“At least,” she said, disengaging herself a little,

“you are with me, my most dear lord, and so there’s

nought to fear.”

They looked around, water running off their

noses and chins. Shea’s heavy woolen shirt was already

so soaked that it stuck to his skin, and Belphebe’s

neat hair was taking on a drowned-rat appearance.

She pointed and cried, “There’s one!”

Shea peered toward a lumpish dark mass that had

a shape vaguely resembling Pete Brodsky.

"Shea?" came a call, and without waiting for a

reply the lump started toward them. As it did so, the

downpour lessened and the light brightened.

"Curse it, Shea!" said Brodsky, as he approached.

"What kind of a box is this? If I couldn't

work my own racket better, I’d turn myself in for

mopery. Where the hell are we?”

“Ohio, I hope,” said Shea. “And look, shamus,

we’re better off than we were, ain’t we? I’m sorry

about this rain, but I didn’t order it.”

“All I got to say is you better be right,” said

Brodsky gloomily. “You can get it all for putting the

snatch on an officer, and I ain’t sure I can square the

rap even now. Where’s the other guy?”

Shea looked around. “Walter may be here, but it

looks as though he didn’t come through to the same

place. And if you ask me, the question is not where

we are but when we are. It wouldn’t do us much

good to be back in Ohio in 700 A.D., which is about

the time we left. If this rain would only let up . . .”

With surprising abruptness the rain did, walking

away in a wall of small but intense downpours.

Spots and bars of sky appeared among the clouds

wafted along by a brisk steady current of air that

penetrated Shea’s wet shirt chillingly, and the sun

shot an occasional beam through the clouds to touch

up the landscape.

It was a good landscape. Shea and his companions

were standing in deep grass, on one of the higher

spots of an extent of rolling ground. This stretch in

turn appeared to be the top of a plateau, falling

away to the right. Mossy boulders shouldered up

through the grass, which here and there gave way to

patches of purple-flowered heather, while daisies

nodded in the steady breeze. Here and there was a

single tree, but down in the valley beyond their plateau

the low land was covered with what appeared at

this distance to be birch and oak. In the distance, as

they turned to contemplate the scene, rose the heads

of far blue mountains.

The cloud-cover thinned rapidly and broke some

more. The air had cleared enough so they could now

see two other little storms sweeping across the middle

distance, trailing their veils of rain. As the

patches of sunlight whisked past, the landscape

blazed with a singularly vivid green, quite unlike that

of Ohio.

Brodsky was the first to speak. “If this is Ohio,

I’m a peterman,” he said. “Listen, Shea, do I got to

tell you again you ain’t got much time? If those yaps

from the D.A.'s office get started on this, you might

just as well hit yourself on the head and save them

the trouble. He’s coming up for election this fall and

needs a nice fat case. And there’s the F.B.I. Rover

boys — they just love snatch cases, and you can’t

put no fix in with them that will stick. So you better

get me back before people start asking questions.”

Shea said, rather desparately, “Pete, I’m doing all

I can. Honest. I haven’t the least idea where we are,

or in what period. Until I do, I don’t dare try sending

us anywhere else. We’ve already picked up a

rather high charge of magical static coming here,

and any spell I used without knowing what kind of

magic they use around here is apt to make us simply

disappear or end up in Hell — you know, real red

hell with flames all around, like in a fundamentalist

church.”

“Okay,” said Brodsky. “You got the office. Me,

I don’t think you got more than a week to get us

back at the outside.”

Belphebe pointed, “Marry, are those not sheep?”

Shea shaded his eyes. “Right you are, darling,”

he said. The objects looked like a collection of lice

on a piece of green baize, but he trusted his wife’s

phenomenal eyesight.

“Sheep,” said Brodsky. One could almost hear

the gears grind in his brain as he looked around.

“Sheep.” A beatific expression spread over his face.

“Shea, you must of done it! Three, two, and out

we’re in Ireland — and if it is, you can hit me on the

head if I ever want to go back.”

Shea followed his eyes. “It does rather look like

it,” he said. “But when . . .”

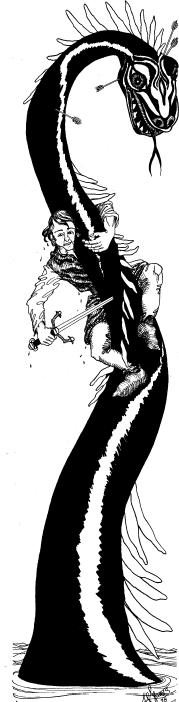

Something went past with a rush of displaced air.

It struck a nearby boulder with a terrific crash and

burst into fragments that whizzed about like pieces

of an artillery shall.

“Duck!” shouted Shea, throwing himself flat and

dragging Belphebe down with him.

Brodsky went into a crouch, lips drawn tight over

his teeth, looking around with quick, jerky motions

for the source of the missile. Nothing more happened.

After a minute, Shea and Belphebe got up

and went over to examine a twenty-pound hunk of

sandy conglomerate.

Shea said, “Somebody is chucking hundredpound

boulders around. This may be Ireland, but I

hope it isn’t the time of Finn McCool or Strongbow.”

“Cripes,” said Brodsky, “and me without my

heater. And you a shiv man with no shiv.”

It occurred to Shea that at whatever period they

had hit this place, he was in a singularly weaponless

state. He climbed on the boulder against which the

missile had destroyed itself and looked in all directions.

There was no sign of life except the distant,

tiny sheep — not even a shepherd or a sheep-dog.

He slid down and sat on a ledge of the boulder and

considered, the stone feeling hard against his wet

back. “Sweetheart,” he said, addressing Belphebe,

“it seems to me that whenever we are, the first thing

we have to do is find people and get oriented. You’re

the guide. Which direction’s the most likely?”

The girl shrugged. “My woodcraft is nought without

trees,” she said, “but if you put it so, I’d seek a

valley, for people ever live by watercourses.”

“Good idea,” said Shea. “Let’s . . .”

Whizz!

Another boulder flew through the air, but not in

their direction. It struck the turf a hundred yards

away, bounced clumsily, and rolled out of sight over

the hill. Still — no one was visible.

Brodsky emitted a growl, but Belphebe laughed.

“we are encouraged to begone,” she said. “Come,

my lord, let us do no less.

At that moment another sound made itself audible.

It was that of a team of horses and a vehicle

whose wheels were in violent need of lubrication.

With a drumming of hooves, a jingle of harness, and

a squealing of wheels, a chariot rattled up the slope

and into view. It was drawn by two huge horses, one

gray and one black. The chariot itself was built more

on the lines of a sulky than those of the open-backed

Graeco-Roman chariot, with a seat big enough for

two or three persons across the back, and the sides

cut low in front to allow for entrance. The vehicle

was ornamented with nail-heads and other trim in

gold, and a pair of scythe-blades jutted from the

hubs.

The driver was a tall, thin freckled man, with red

hair trailing from under his golden fillet down over

his shoulders. He wore a green kilt and over that a

deerskin cloak with arm-holes at elbow length.

The chariot sped straight toward Shea and his

companions, who dodged away from the scythes

round the edge of the boulder. At the last minute the

charioteer reined to a walk and shouted, “Be off

with you if you would keep the heads on your shoulders!”

“Why?” asked Shea.

“Because himself has a rage on. It is tearing up

trees and casting boulders he is, and a bad hour it

will be for anyone who meets him the day.”

“Who is himself?” said Shea, almost at the same

time as Brodsky said, “Who the hell are you?”

The charioteer pulled up with an expression of astonishment

on his face. “I am Laeg mac Riangabra,

and who would himself be but Ulster’s hound, the

glory of Ireland, Cuchulainn the mighty? He is after

killing his only son and has worked himself into a

rage. Ara! It is runing the countryside he is, and the

sight of you Fomorians would make him the

wilder.”

The charioteer cracked his whip, and the horses

raced off over the hill, the flying clods dappling the

sky. In the direction from which he had come, a

good-sized sapling with dangling roots rose against

the horizon and fell back.

“Hey!” said Brodsky, tagging after them. “Come

on back and pal up with this ghee. He’s the number

one hero of Ireland.”

Another rock bounced on the sward and from the

distance a kind of howling was audible.

“I’ve heard of him,” said Shea, “and if you want

to, we can drop in on him later, but I think that right

now is a poor time for calls. He isn’t in a pally

mood.”

Belphebe said, “You name him hero, and yet you

say he has slain his own son. How can this be?”

Brodsky said, “It was a bum rap. This Cuchulainn

got his girlfriend Aoife pregnant way back

when and then gave her the air, see? So she’s sore at

him, see? So when the kid grows up, she sends him

to Cuchulainn under a geas . . .”

“A moment,” said Belphebe. “What would this

geas be?”

“A taboo,” said Shea.

Brodsky said, “It’s a hell of a lot more than that.

You got one these geasa on you and you can’t do the

thing it’s against even if it was to save you from the

hot seat. So like I was saying this young ghee, his

name is Conla, but he has this geas on him not to tell

his name or that of his father to anyone. So when

Aoife sends him to Cuchulainn, the big shot challenges

the kid and then knocks him off. It ain’t

good.”

“A tale to mourn, indeed,” said Belphebe. “How

are you so wise in these matters, Master Pete? Are

you of this race?”

“I only wisht I was,” said Brodsky fervently. “It

would do me a lot of good on the force. But I ain’t,

so I dope it this way, see? I’ll study this Irish stuff

till I know more about it than anybody. And then I

got innarested, see?”

They were well down the slope now, the grass

dragging at their feet, approaching the impassive

sheep.

Belphebe said, “I trust we shall come soon to

where there are people. My bones protest I have not

dined.”

“Listen,” said Brodsky, “This is Ireland, the best

country in the world. If you want to feed your face,

just knock off one of them sheep. It’s on the house.

They run the pitch that way.”

“We have neither knife nor fire,” said Belphebe.

“I think we can make out on the fire deal with the

metal we have on us and a piece of flint,” said Shea.

“And if we have a sheep killed and a fire going, I’ll

bet it won’t be long before somebody shows up with

a knife to share our supper. Anyway, it’s worth a

try.”

He walked over to a big tree and picked up a

length of dead branch that lay near the base. By

standing on it and heaving, he broke it somewhat

raggedly in half, handing one end to Brodsky. The

resulting cudgels did not look especially efficient,

but they could be made to do.

“Now,” said Shea, “if we hide behind that boulder,

Belphebe can circle around and drive the flock

toward us.”

“Would you be stealing our sheep now, darlings?”

said a deep male voice.

Shea look around. Out of nowhere, a group of

men had appeared, standing on the slope above

them. There were five of them, in kilts or trews, with

mantles of deerskin or wolfhide fastened around

their necks. One of them carried a brassbound club,

one a clumsy-looking sword, and the other three,

spears.

Before Shea could say anything, the one with the

club said, “The heads of the men will look fine in

the hall, now. But I will have the woman first.”

“Run!” cried Shea, and took his own advice. The

five ran after them.

Belphebe, being unencumbered, soon took the

lead. Shea clung to his club, hating to have nothing

to hit back with if he were run down. A glance backward

showed that Brodsky had either dropped his or

thrown it at the pursuers without effect.

“Shea!” yelled the detective. “Go on — they got

me!”

They had not, as a matter of fact, but it was clear

they soon would. Shea paused, turned, snatched up

a stone about the size of a baseball, and threw it past

Brodsky’s head at the pursuers. The spearmantarget

ducked, and they came on, spreading out in a

crescent to surround their prey.

“I — can’t — run no more,” panted Brodsky.

“Go on.”

“Like hell,” said Shea. “We can’t go back without

you. Let’s both take the guy with the club.”

The stones arched through the air simultaneously.

The clubman ducked, but not far enough; one missile

caught his leather cap and sent him sprawling to

the grass.

The others whooped and closed in with the evident

intention of skewering and carving, when a terrific

racket made everyone pause on tiptoe. Down the

slope came the chariot that had passed Shea and his

group before. The tall, red-haired charioteer was

standing in the front, yelling something like “Ulluul-

lu” while balancing in the back was a smaller, rather

dark man.

The chariot bounded and slewed toward them.

Before Shea could take in the whole action, one of

the hub-head scythes caught a spearman, shearing

off both legs neatly, just below the knee. The man

fell, shrieking, and at the same instant the small man

drew back his arm and threw a javelin right through

the body of another.

“It is himself!” cried one of them, and the survivors

turned to run.

The small dark fellow spoke to the charioteer,

who pulled up his horses. Cuchulainn leaped down

from the vehicle, took a sling from his belt and

whirled it around his head. The stone struck one of

the men in the back of the neck, and down he went.

As the man fell, Cuchulainn wound up a second

time. Shea thought this one would miss for sure, as

the man was now a hundred yards away and going

farther fast. But the missile hit him in the head, and

he pitched on his face.

“Get out the head bag and fetch me the trophies,

dear,” said Cuchulainn.

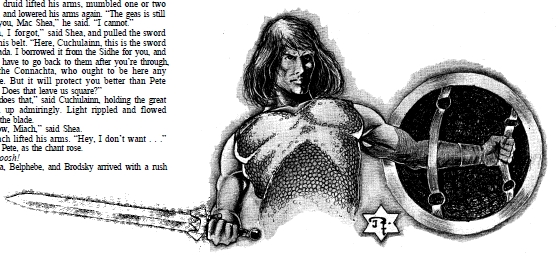

II

Laeg rummaged in the rear of the chariot and produced

a large bag and a heavy sword, with which he

went calmly to work. Belphebe had turned back, as

the rescuer came toward the three. Shea saw a smallish

man with curly black hair, not older than himself;

heavy black eyebrows and only a faint fuzz on

his cheeks to compare with the heavy beards of the

defunct five. He was not only an extremely handsome

man; there was also a powerful play of musculature

under his loose outer garment. The hero’s face

bore an expression of settled and brooding melancholy,

and he was dressed in a long-sleeved white

cloak embroidered with gold thread, over a red

tunic.

“Thanks a lot,” said Shea. “You just saved our

lives, in case you wondered. How did you happen

along?”

“'Twas Laeg came to me with a tale of three

strangers, who might be Fomorians by the look to

them, and they were like to be set on by the Lagenians.

Now I will be fighting any man in Ireland that

gives me the time, but unless you are a hero it is not

good to fight at five to two, and it is time that these

pigs of Lagenians learned their manners. So now it is

time for you to be telling me who you are and where

you come from and whither bound. If you are indeed

Fomorians, the better for you — King Conchobar

is friends with them this year, or I might be making

you by the head shorter.”

Shea searched his mind for details of the culturepattern

of the men of Cuchulainn’s Ireland. A slip at

the beginning might result in their heads being added

to the collection bumping each other in Laeg’s bag

like so many cantaloupes. Brodsky beat him to the

punch.

“Jeepers!” he said, in a tone which carried its

own message. “Imagine holding heavy with a zinger

like you! I’m Pete Brodsky — give a toss to my

friends here, Harold Shea and his wife Belphebe.”

He stuck out his hand.

“We do not come from Fomoria, but from

America, an island beyond their land,” said Shea.

Cuchulainn acknowledged the introduction to

Shea with a stately nod of courtesy. His eyes swept

over Brodsky, and he ignored the outthrust hand.

He addressed Shea. “Why do you travel in company

with such a mountain of ugliness, dear?”

Out of the corner of his eye, Shea could see the

cop’s wattles swell dangerously. He said hastily;

“He may be no beauty, but he’s useful. He’s our

slave and bodyguard, a good fighting man. Shut up,

Pete!”

Brodsky had sense enough to do so. Cuchulainn

accepted the explanation with the same sad courtesy

and gestured toward the chariot. “You will be

mounting up in the back of my car, and I will drive

you to my camp, where there will be an eating before

you set out on your journey again.”

He climbed to the front of the chariot himself,

while the three wanderers clambered wordlessly to

the back seat and held on. Laeg, having disposed of

the head bag, touched the horses with a golden goad.

Off they went. Shea found the ride a monstrously

rough one, for the vehicle had no springs and the

road was distinguished by its absence, but Cuchulainn

lounged in the seat, apparently at ease.

Presently there loomed ahead a small patch of

woods at the bottom of a valley. Smoke rose from a

fire. The sun had decided to resolve the question of

what time of day it was by setting, so that the hollow

lay in shadow. A score or more of men, rough and

wild-looking, got to their feet and cheered as the

chariot swept into the camp. At the center of it a

huge iron pot bubbled over the fire, and in the background

a shelter of poles, slabs of bark and branches

had been erected. Laeg pulled up the chariot and

lifted the head bag with its lumpish trophies, and

there was more cheering.

Cuchulainn sprang down lightly, acknowledged

the greeting with a casual wave, then swung to Shea.

“Mac Shea, I am thinking that you are of quality,

and as you are not altogether the ugliest couple in

the world, you will be eating with me.” He waved an

arm. “Bring the food, darlings.”

Cuchulainn’s henchmen busied themselves, with a

vast amount of shouting, and running about in patterns

that would have made good cat’s cradles. One

picked up a stool and carried it across the clearing; a

second immediately picked it up again and took it

back to where it had been.

“Do you think they’ll ever get around to feeding

us?” said Belphebe in a low tone. But Cuchulainn

merely looked on with a slight smile, seeming to regard

the performance as somehow a compliment to

himself.

After an interminable amount of coming and going,

the stool was finally established in front of the

lean-to. Cuchulainn sat down on it and with a wave

of his hand, indicated that the Sheas were to sit on

the ground in front of him. The charioteer Laeg

joined them on the ground, which was still decidedly

damp after the rain. But, as their clothes had not

dried, it didn’t seem to matter.

A man brought a large wooden platter on which

were heaped the champion’s victuals, consisting of a

huge cut of boiled pork, a mass of bread, and a

whole salmon. Cuchulainn laid it on his knees and

set to work on it with fingers and his dagger, saying

with a ghost of a smile, “Now according to the custom

of Ireland, Mac Shea, you may challenge the

champion for his portion. A man of your inches

should be a blithe swordsman, and I have never

fought with an American.”

“Thanks,” said Shea, “but I don’t think I could

eat that much, anyway, and there’s a — what do you

call it? — a geas against my fighting anyone who has

done something for me, so I couldn’t after the way

you saved us.” He addressed himself to the slab of

bread on which had been placed a pork chop and a

piece of salmon, then glanced at Belphebe and

added, “Would it be too much trouble to ask for the

loan of a pair of knives? We left in rather a hurry

and without our tools.”

A shadow flitted across the face of Cuchulainn.

“It is not well for a man of his hands to be without

his weapons. Are you sure, now, that they were not

taken away from you?”

Belphebe said, “We came here on a magical spell,

and as you doubtless know, there are some that cannot

be spelled in the presence of cold iron.”

“And what could be truer?” agreed Cuchulainn.

He clapped his hands and called, “Bring two knives,

darlings. The iron knives, not the bronze.” He

chewed, looking at Belphebe. “And where would

you be journeying to, darlings?”

Shea said, “Back to America, I suppose. We sort

of — dropped in to see the greatest hero in Ireland.”

Cuchulainn appeared to take the compliment as a

matter of course. “You come at a poor time. The expedition

is over, and now I am going home to sit

quietly with my wife Emer, so there will be no fighting.”

Laeg looked up with his mouth full and said,

“You will be quiet if Meddling Maev and Ailill will

let you, Cucuc. Some devilment they will be getting

up, or it is not the son of Riangabra I am.”

“When my time comes to be killed by the Connachta,

then I will be killed by the men of Connacht,”

said Cuchulainn, composedly. He was still

looking at Belphebe.

Belphebe asked, “Who stands at the head of the

magical art here?”

Cuchulainn said, “It is true that you said you have

a taste for magic. None is greater, nor will be, than

Ulster’s Cathbadh, adviser to King Conchobar. And

now you will come with me to Muirthemne in the

morning, rest and fit yourselves, and we will go to

Emain Macha to see him together.”

He laid aside his platter and took another look at

Belphebe. The little man was as good with a trencher

as he was with a sling; there was practically nothing

left, and he had had twice as much as Shea.

“That’s extremely kind of you,” said Shea. “Very

kind indeed.” It was so very kind that he felt a

twinge of suspicion.

“It is not,” said Cuchulainn. “For those with the

gift of beauty, it is no more than their due that they

should receive all courtesy.”

He was still looking at Belphebe, who glanced

up at the darkening sky. “My lord,” she said, “I am

somewhat foredone. Would it not be well to seek our

rest?”

Shea said, “It’s an idea. Where do we sleep?”

Cuchulainn waved a hand toward the grove.

“Where you will, darlings. No one will disturb you

in the camp of Cuchulainn.” He clapped his hands.

“Gather moss for the bed of my friends.”

When they were alone, Belphebe said in a low

voice: “I like not the manner of his approach,

though he has done us great good. Cannot you use

your art to transport us back to Ohio?”

Shea said, “I’ll take a chance on trying to work

out the sorites in the morning. Remember, it won’t

do us any good to get back alone. We’ve got to take

Pete, or we’ll be up on a charge of kidnapping or

murdering him, and I don’t want to go prowling

through this place at night looking for him. Besides,

we need light to make the passes.”

Early as they rose, the camp was already astir

about them and a fire lighted. As Shea and Belphebe

wandered through the camp, looking for Brodsky,

they noted it was strangely silent, the elaborate confusion

of the previous evening being carried on in

whispers or dump show. Shea grabbed the arm of a

bewhiskered desperado hurrying past with a bag of

something to inquire the reason.

The man bent close and said in a fierce whisper,

“Sure, ‘tis that himself is in his sad mood, and keeping

his booth. If you would lose your head, it would

be just as well to make a noise.”

“There’s Pete,” said Belphebe.

The detective waved a hand and came toward

them from under the trees. He had somehow acquired

one of the deerskin cloaks, which was held

under his chin with a brass brooch, and he looked

unexpectedly cheerful.

“What’s the office?” he asked in the same stage

whisper the others were using, as he approached

them.

“Come with us,” said Shea. “We’re going to try

to get back to Ohio. Where’d you get the new

clothes?”

“Aw, one of these muzzlers thought he could

wrestle, so I slipped him a little jujitsu and won it.

Listen, Shea, I changed my mind. I ain’t going back.

This is the real McCoy.”

“But we want to go back,” said Belphebe, “and

you told us just yesterday that if we showed up without

you, our fate would be less than pleasant.”

“Listen, give it a rest. I’m on the legit here, and

with that magical stuff of yours, you could be, too.

At least I want to stay for the big blow.”

“Come this way,” said Shea, leading away from

the center of the camp to where there was less danger

of their voices causing trouble. “What do you mean

by the big blow?”

“From what I got,” said Pete, “I figured out

when we landed. This Maev and Ailill are rustling

out the mob and heeling them up to give Cuchulainn

a bang on the head. They got all the cousins of people

he’s bumped off in on the caper, and they’re going

to put a geas on him that will make him go up

against them all at once, and then boom. I want to

stay for the payoff.”

“Look here,” said Shea, “you said only yesterday

that we had to get you back within a week. Remember?

It was something about your probably being

seen going into our house and not coming out.”

“Sure, sure. And if we go back, I’ll alibi you. But

what for? I’m teaching these guys to wrestle, and

what with your magic, maybe you could even take

the geas off the big shot and he wouldn’t get shoved

over.”

“Perhaps I could at that,” said Shea. “It seems to

amount to a kind of psychological compulsion by

magical means, and between psychology and magic,

I ought to make it. But no — it’s too risky. I daren’t

take the chance with him making eyes at Belphebe.”

They had emerged from the clump of trees and

were at the edge of the slope, with the early sun just

touching the tops of the branches above them. Shea

went on, “I’m sorry, Pete, but Belphebe and I don’t

want to spend the rest of our lives here, and if we’re

going, we’ve got to go now. As you said. Now, you

two hold hands. Give me your other hand, Belphebe.”

Brodsky obeyed with a somewhat sullen expression.

Shea closed his eyes, and began: “If either A or

(B or C) is true, and C or D is false . . .” motioning

with his free hand to the end of the sorites.

He opened his eyes again. They were still at the

edge of a clump of trees, on a hill in Ireland, watching

the smoke from the fire as it rose above the trees

to catch the sunshine.

Belphebe asked, “What’s amiss?”

“I don’t know,” said Shea desperately. “If I only

had something to write with, so I could check over

the steps . . . No, wait a minute. Making this work

depends on a radical alteration of sense impressions

in accordance with the rules of symbolic logic and

magic. Now we know that magic works here, so that

can’t be the trouble. But for symbolic logic to be effective,

you have to submit to its effects — that is, be

willing. Pete, you’re the villain of the piece. You

don’t want to go back.”

“Don’t put the squeeze on me,” said Brodsky.

“I’ll play ball.”

“All right. Now I want you to remember that

you’re going back to Ohio, and that you have a good

job there and like it. Besides, you were sent out to

find us, and you did. Okay?”

They joined hands again and Shea, constricting

his brow with effort, ran through the sorites again,

this time altering one or two of the terms to give

greater energy. As he reached the end, time seemed

to stand still for a second; then crash! and a flash of

vivid blue lightning struck the tree nearest them,

splitting it from top to bottom.

Belphebe gave a little squeal, and a chorus of excited

voices rose from the camp.

Shea gazed at the fragments of the splintered tree

and said soberly, “I think that shot was meant for

us, and that that just about tears it, darling. Pete,

you get your wish. We’re going to have to stay here

at least until I know more about the laws controlling

magic in this continuum.”

Two or three of Cuchulainn’s men burst excitedly

through the trees and came toward them,

spears ready. “Is it all right that you are?” one of

them called.

“Just practicing a little magic,” said Shea, easily.

“Come on, let’s go back and join the others.”

In the clearing voices were no longer quenched,

and the confusion had become worse than ever.

Cuchulainn stood watching the loading of the chariot,

with a lofty and detached air. As the three travelers

approached he said, “Now it is to you I am grateful,

Mac Shea, with your magical spell for reminding

me that things are better done at home than abroad.

It is leaving at once we are.”

“Hey!” said Brodsky. “I ain’t had no breakfast.”

The hero regarded him with distaste. “You will be

telling me that I should postpone the journey for the

condition of a slave’s belly?” he said, and turning to

Shea and Belphebe, “We can eat as we go.”

The ride was smoother than the one of the previous

day only because the horses went at a walk so as

not to outdistance the column of retainers on foot.

Conversation over the squeaking of the wheels began

by being sparse and rather boring, with Cuchulainn

keeping his chin well down on his chest. But he

apparently liked Belphebe’s comments on the beauty

of the landscape. As it came on to noon he began to

chatter, addressing her with an exclusiveness that

Shea found disturbing, though he had to admit that

the little man talked well, and always with the most

perfect courtesy.

The country around them got lower and flatter

and flatter and lower, until from the tops of the few

rises Shea glimpsed a sharp line of gray-blue across

the horizon; the sea. A shower came down and temporarily

soaked the column, but nobody paid it

much attention, and in the clear sunlit air that followed

everyone was soon dry. Cultivation became

more common, though there was still less of it than

pasturage. Occasionally a lumpish-looking serf, clad

in a length of ragged sacking-like cloth wrapped

around his middle and a thick veneer of dirt, left off

his labors to stare at the band and wave a languid

greeting.

At last, over the manes of the horses, Shea saw

that they were approaching a stronghold. This consisted

of a stockade of logs with a huge double gate.

Belphebe surveyed it critically and whispered behind

her hand to Shea, “It could be taken with fire-earrows.”

“I don’t think they have many archers or very

good ones,” he whispered back. “Maybe you can

show them something.”

The gate was pushed open creakingly by more

bearded warriors, who shouted: “Good-day to you,

Cucuc! Good luck to Ulster’s hound!”

The gate was wide enough to admit the chariot,

scythe-blades and all. As the vehicle rumbled

through the opening, Shea glimpsed houses of various

shapes and sizes, some of them evidently stables

and barns. The biggest of all was the hall in the middle,

whose heavily thatched roof came down almost

to the ground at the sides.

Laeg pulled up. Cuchulainn jumped down, waved

his hand, and cried, “Muirthemne welcomes you,

Americans!” All the others applauded as though he

had said something particularly brilliant.

He turned to speak to a fat man, rather better

dressed than the rest, when another man came out of

the main hall and walked rapidly toward them. The

newcomer was a thin man of medium height, elderly

but vigorous, slightly bent and carrying a stick, on

which he leaned now and again. He had a long white

beard, and a purple robe covered him from neck to

ankle.

“The best of the day to you, Cathbadh,” said

Cuchulainn. "This is surely a happy hour that brings

you here, but where is my darling Emer?”

“Emer has gone to Emain Macha,” said Cathbadh.

“Conchobar summoned her . . .”

“Ara!” shouted Cuchulainn. “Is it a serf that I

am, that the King can send for my wife every time he

takes it into the head of him? He is . . .”

“It is not that at all, at all,” said Cathbadh. “He

summons you, too, and for that he sent me instead

of Levarcham, for he knows you might not heed her

word if you took it into that willful head of yours to

disobey, whereas it is myself can put a geas on you to

go.”

“And why does himself want us at Emain

Macha?”

“Would I be knowing all the secrete in the heart

of a King?”

Shea asked, “Are you the court druid?”

Cathbadh became aware of him for the first time,

and Cuchulainn made introductions. Shea explained,

“It seems to me that the King might want

you at the court for your own protection, so the

druids can keep Maev’s sorcerers from putting a

spell on you. That’s what she’s going to do.”

“How do you know of this?” asked Cathbadh.

“Through Pete here. He sometimes knows about

things that are going to happen before they actually

take place. In our country we call it second sight.”

Cuchulainn wrinkled his nose. “That ugly slave?”

“Yeh, me,” said Brodsky, who had approached

the group. “And you better watch your step, handsome,

because somebody’s going to hang you up to

dry unless you do something about it.”

“If it is destined none can alter it,” said Cuchulainn.

“Fergus! Have the bath water heated.” He

turned to Shea. “Once you are properly washed and

garbed you will look well enough for the board in

my beautiful house. I will lend you some proper garments,

for I cannot bear the sight of those Formorian-

like rags."

III

Along the side of the main hall was an alcove

made of screens of wattle, set at an angle that provided

privacy for those within. In the alcove stood

Cuchulainn’s bathtub, a large and elaborate affair

of bronze. A procession of the women of the manor

were now coming in from the well with jugs of

water, which they emptied into the tub. Meanwhile

the men were poking up the fire at the end of the hall

and adding a number of stones of about five to ten

pounds’ weight.

Brodsky sidled up to Shea, as they stood in the

half-light, orienting themselves. “Listen, I don’t

want to blow the whistle on a bump rap, but you better

watch it. The racket they have here, this guy can

make a pass at Belphebe in his own house, and it’s

legit. You ain’t got no beef coming.”

“I was afraid of that,” said Shea, unhappily.

“Look there.”

“There” was a row of wooden spikes projecting

from one of the horizontal strings along the wall,

and most of these spikes were occupied by human

heads. As they watched Laeg brought in the head

bag and added the latest trophies to the collection,

pressing them down firmly. Some of those already in

place were quite fresh, while others had been there

so long that there was little left of them but a skull

with a little hair adhering to the scalp.

“Jeepers!” said Brodsky, “and if you start beefing,

he’ll put you there, too. Give me time — I’ll try

to think of some way to rumble his line.”

“Make way!” shouted a huge bewhiskered retainer.

The three dodged as the man ran past them, carrying

a large stone, smoking from the fire, in a pair

of tongs. The man dashed into the alcove. There was

a splash and a loud hiss. Another retainer followed

with a second stone while the first was on his return

trip. In a few minutes all the stones had been transferred

to the bathtub. Shea looked around the screen

and saw that the water was steaming gently.

Cuchulainn sauntered past into the bathroom and

tested the water with an inquisitive finger. “That

will do, dears.”

The retainers picked the stones out of the water

with their tongs and piled them in the corner, then

went around from behind the screen. Cuchulainn

reached up to pull off his tunic, then saw Shea.

“I am going to undress for the bath,” he said.

“Surely, you would not be wanting to remain here,

now.”

Shea turned back into the main room just in time

to see Brodsky smack one fist into the other palm.

“Got it!”

“Got what?” said Shea.

“How to needle his hot tomato.” He looked

around, then pulled Shea and Belphebe closer. “Listen,

the big shot putting the scram on you now just

reminded me. The minute he makes a serious pass at

you, Belle, you gotta go into a strip-tease act. In

public, where everybody can get a gander at it.”

Belphebe gasped. Shea asked, “Are you out of

your head? That sounds to me like trying to put a

fire out with gasoline.”

“I tell you he can’t take it!” Brodsky’s voice was

low but urgent. “They can’t none of them. One time

when this guy was going to put the slug on everyone

at the court, the King sent out a bunch of babes with

bare knockers, and they nearly had to pick him up in

a basket.”

“I like this not,” said Belphebe, but Shea said,

“A nudity taboo! That could be part of a culture

pattern, all right. Do they all have it?”

“Yeh, and but good,” said Brodsky. “They even

croak of it. What gave me the tip was him putting

the chill on you before he started to undress — he

was doing you a favor.”

Cuchulainn stepped out of the alcove, buckling a

belt around a fresh tunic, emerald-green with

embroidery of golden thread. He scrubbed his long

hair with a towel and ran a comb through it, while

Laeg took his place behind the screen.

Belphebe said, “Is there to be but one water for

all?”

Cuchulainn said, "There is plenty of soapwort.

Cleanliness is good for beauty.” He glanced at

Brodsky. “The slave can bathe in the trough outside.”

“Listen . .” began Brodsky, but Shea put a hand

on his arm, and to cover up, asked, “Do your druids

use spells of transportation — from one place to

another?”

“There is little a good druid cannot do — but I

would advise you not to use the spells of Cathbadh

unless you are a hero as well as a maker of magic,

for they arc very mighty.”

He turned to watch the preparations for dinner

with a sombre satisfaction. Laeg presently appeared,

his toilet made, and from another direction one of

the women brought garments which she took into

the bathroom for Shea and Belphebe. Shea started

to follow his wife, but remembered what Brodsky

had said about the taboo, and decided not to take a

chance on shocking his hosts. She came out soon

enough in a floor-length gown that clung to her all

over, and he noted with displeasure that it was the

same green and embroidered patterns as

Cuchulainn’s tunic.

After Shea had dealt with water almost cold and a

towel already damp, his own costume turned out to

be a saffron tunic and tight knitted scarlet trews

which he imagined as looking quite effective.

Belphebe was watching the women around the

fire. Over in the shadows under the eaves sat Pete

Brodsky, cleaning his fingernails with a bronze

knife, a chunky, middle-aged man — a good hand

in a fight, with his knowledge of jujitsu and his

quick reflexes, and not a bad companion. Things

would be a lot easier, though, if he hadn’t fouled up

the spell by wanting to stay where he was, Or had

that been responsible?

Old Cathbadh came stumping up with his stick.

“Mac Shea,” he said, “the Little Hound is after

telling me that you also are a druid, who came here

by magical arts from a distant place, and can

summon lightning from the skies.”

“It’s true enough,” said Shea. “Doubtless you

know those spells.”

“Doubtless I do,” said Cathbadh, looking sly.,

“We must hold converse on matters of our craft. We

will be teaching each other some new spells, I am

thinking.”

Shea frowned. The only spell he was really interested

in was one that would take Belphebe and

himself — and Pete — back to Garaden, Ohio,

and Cathbadh probably didn’t know that one. It

would be a question of getting at the basic assumptions,

and more or less working out his own method

of putting them to use.

Aloud he said, “I think we can be quite useful to

each other. In America, where I come from, we have

worked out some of the general principles of magic,

so that it is only necessary to learn the procedures in

various places.”

Cathbadh shook his head. “You do be telling

me — and it is the word of a druid, so I must believe

you — but ‘tis hard to credit that a druid

could travel among the Scythians of Greece or the

Scots of Egypt, with all the strange gods they do be

having, and still be protected by his spells as well as

at home.”

Shea got a picture of violently confused geography.

But then, he reflected, the correspondence

between this world and his own would only be

rough, anyway. There might be Scots in Egypt here.

Just then Cuchulainn came out of his private

room and sat down without ceremony at the head of

the table. The others gathered round. Laeg took the

place at one side of the hero and Cathbadh at the

other. Shea and Belphebe were nodded to the next

places, opposite each other. A good-looking serf

woman with hair bound back from her forehead

filled a large golden goblet at Cuchulainn’s place

with wine from a golden ewer, then smaller silver

cups at the places of Laeg and Cathbadh, and

copper mugs for Shea and Belphebe. Down the table

the rest of the company had leather jacks and barley

beer.

Cuchulainn said to Cathbadh, “Will you make

the sacrifice, dear?”

The druid stood up, spilled a few drops on the

floor and chanted to the gods Bile, Danu, and Ler.

Shea decided that it was only imagination that he

was hearing the sound of beating wings, and only the

approach of the meal that gave him a powerful sense

of internal comfort, but there was no doubt that

Cathbadh knew his stuff.

He knew it, too. “Was that not fine, now?” he

said, as he sat down next to Shea. “Can you show

me anything in your outland magic ever so good?”

Shea thought. It wouldn’t do any harm to give the

old codger a small piece of sympathetic magic, and

might help his own reputation. He said, “Move your

wine-cup over next to mine, and watch it carefully.”

There would have to be a spell to link the two if he

were going to make Cathbadh’s wine disappear as he

drank his own, and the only one he could think of at

the moment was the “Double, double” from

“Macbeth.” He murmured that under his breath,

making the hand passes he had learned in Faerie.

Then he said, “Now, watch,” picked up his mug

and set it to his lips.

Whoosh!

Out of Cathbadh’s cup a geyser of wine leaped as

though driven by a pressure hose, nearly reaching

the ceiling before it broke up to descend in a rain of

glittering drops, while the guests at the head of the

table leaped to their feet to draw back from the phenomenon.

Cathbadh was a fast worker; he lifted his

stick and struck the hurrying stream of liquid, crying

something unintelligible in a high voice. Abruptly

the gusher was quenched and there was only the

table, swimming with wine, and serf women rushing

to mop up the mess.

Cuchulainn said, “This is a very beautiful piece of

magic, Mac Shea, and it is a pleasure to have so notable

a druid among us. But you would not be

making fun of us, would you?” He looked dangerous.

“Not me,” said Shea. “I only. . .”

Whatever he intended to say was cut off by a

sudden burst of unearthly howling from somewhere

outside. Shea glanced around rather wildly, feeling

that things were getting out of hand. Cuchulainn

said, “You need not be minding that at all, now. It

will only be Uath, and because the moon has reached

her term.”

“I don’t understand,” said Shea.

“The women of Ulster were not good enough for

Uath, so he must be going to Connacht and courting

the daughter of Ollgaeth the druid. This Ollgaeth is

no very polite man; he said no Ultonian should have

his daughter, and when Uath persisted, he put a geas

on Uath that when the moon fills he must howl the

night out, and a geas on his own daughter that she

cannot abide the sound of howling. I am thinking

that Ollgaeth’s head is due for a place of honor.” He

looked significantly at his collection.

Shea said, “But I still don’t understand. If you

can put a geas on someone, can’t it be taken off

again?”

Cuchulainn looked mournful, Cathbadh embarrassed,

and Laeg laughed. “Now you will be making

Cathbadh sad, and our dear Cucuc is too polite to

tell you, but the fact is no other than that Ollgaeth is

so good a druid that no one can lift the spells he lays,

nor lay one he cannot lift.”

Outside, Uath’s mournful howl rose again.

Cuchulainn said to Belphebe, “Does he trouble you,

dear? I can have him removed, or the upper part of

him.”

As the meal progressed, Shea noticed that

Cuchulainn was putting away an astonishing

quantity of the wine, talking almost exclusively with

Belphebe, although the drink did not seem to have

much effect on the hero but to intensify his sombre

courtesy. But, when the table was cleared, he lifted

his goblet to drain it, looked at Belphebe from

across the table, and nodded significantly.

Shea got up and ran around the table to place a

hand on her shoulder. Out of the corner of his eye,

he saw Pete Brodsky getting up, too. Cuchulainn’s

face bore the faintest of smiles. “It is sorry to discommode

you I am,” he said, “but this is by the

rules and not even a challenging matter. So now,

Belphebe, darling, you will just come to my room.”

He got up and started toward Belphebe, who got

up, too, backing away. Shea tried to keep between

them and racked his brain hopelessly for some kind

of spell that might stop this business. Everyone else

was standing up and pushing to watch the little

drama.

Cuchulainn said, “Now you would not be getting

in my way, would you, Mac Shea, darling?” His

voice was gentle, but there was something incredibly

ferocious in the way he uttered the words, and Shea

suddenly realized he was facing a man who had a

sword. Outside, Uath howled mournfully.

Beside him, Belphebe herself suddenly leaped for

one of the weapons hanging on the wall and tugged,

but in vain. It had been so securely fastened with

staples that it would have taken a pry bar to get it

loose. Cuchulainn laughed.

Behind and to the left of Shea, Brodsky’s voice

rose, “Belle, you stiff, do like I told you!”

She turned back as Cuchulainn drew nearer and

with set face crossed her arms and whipped the green

gown off over her head. She stood in her underwear.

There was a simultaneous gasp and groan of

horror from the audience. Cuchulainn stopped, his

mouth coming open.

“Go on!” yelled Brodsky in the background.

“Give it the business!”

Belphebe reached behind her to unhook her

brassiere. Cuchulainn staggered as though he had

been struck. He threw one arm across his eyes,

reached the table and brought his face down on it,

pounding the wood with the other fist.

“Ara!” he shouted. “Take her away! Is it killing

me you will be and in my own hall, and me your host

that has saved your life?”

“Will you let her alone?” asked Shea.

“I will that for the night.”

“Mac Shea, take his offer,” advised Laeg from

the head of the table. He looked rather greenish

himself. “If his rage comes on him, none of us will

be safe.”

Okay. Honest,” said Shea and held Belphebe’s

dress for her.

There was a universal sigh of relief from the background.

Cuchulainn staggered to his feet. It is not

feeling well that I am, darlings,” he said and,

picking up the golden ewer of wine, made for his

room.

IV

There was a good deal of excited gabble among

the retainers as Belphebe walked back to her place

without looking to right or left, but they made room

for Shea and Brodsky to join her. The druid looked

shrewdly at the closed door and said, “If the Little

Hound drinks too much by himself, he may be

brooding on the wrong you are after doing him, and

a sad day that would be. If he comes out with the

hero-light playing round his head, run for your

lives."

Belphebe said, “But where would we go.”

“Back to your own place. Where else?”

Shea frowned. “I’m not sure. . .” he began, when

Brodsky cut in suddenly, “Say,” he said, “your

boss ain’t really got no right to get bugged up. We

had to play it that way?"

Cathbadh swung to him. “And why, serf?”

“Don’t call me serf. She’s got a fierce geas on her.

Any guy that touches her gets a bellyache and dies of

it. Her husband only stands it because he’s a magician.

It’s lucky we put the brakes on before the boss

got her in that room, or he’d be ready for the lilies

right now."

Cathbadh’s eyebrows shot up like a seagull taking

off. “Himself should know of this,” he said.

“There would be less blood shed in Ireland if more

people opened their mouths to explain things before

they put their feet in them.”

He got up, went to the bedroom door and

knocked. There was a growl from within, Cathbadh

entered, and a few minutes later came out with

Cuchulainn. The later’s step was visibly unsteady,

and his melancholy seemed to have deepened. He

walked to the head of the table and sat down in the

chair again.

“Sure, and this is the saddest tale in the world I’m

hearing about your wife having such a bad geas on

her. The evening is spoilt and all.. I hope the black fit

does not come on me, for then it will be blood and

death I need to restore me.”

There were a couple of gasps audible and Laeg

looked alarmed, but Cathbadh said hastily, “The

evening is not so spoilt as you think Cucuc. This

Mac Shea is evidently a very notable druid and spell

maker, but I think I am a better. Did you notice how

quickly I put down his wine fountain? Would it not

lift your heart, now, to see the two of us engage in a

contest of magic?”

Cuchulainn clapped his hands. “Never was truer

word spoken. You will just do that, darlings.”

Shea said, “I’m afraid I can’t guarantee . . .” but

Belphebe plucked his sleeve and with her head close

to his, whispered, “ Do it. There is a danger here.”

“It isn’t working right,” Shea whispered back.

Outside rose the mournful sound of Uath’s

howling. “Can you not use your psychology on him

out there?” the girl asked. “It will be magic to

them.”

“A real psychoanalysis would take days,” said

Shea. “Wait a minute, though — we seem to be in

a world where the hysteric type is the norm. That

means a high suggestibility, and we might get something

out of post-hypnotic suggestion.”

Cuchulainn from the head of the table said, “It is

not all night we have to wait.”

Shea turned round and said aloud, “How would it

be if I took the geas off that character out there

training to be a bar-room tenor? I understand that’s

something Cathbadh hasn’t been able to do.”

Cathbadh said, “If you can do this, it will be a

thing worth seeing, but I will not acknowledge you

can do it until I have seen it.”

"All right,” said Shea. “Bring him in.”

“Laeg, dear, go get us Uath,” said Cuchulainn.

He took a drink, looked at Belphebe and his expression

became morose again.

Shea said, “Let’s see. I want a small bright object.

May I borrow one of your rings, Cuchulainn? That

one with the big stone would do nicely.”

Cuchulainn slid the ring down the table as Laeg

returned, firmly gripping the arm of a stocky young

man, who seemed to be opposing some resistance to

the process. Just as they got in the door Uath flung

back his head and emitted a blood-curdling howl.

Laeg dragged him forward, howling away.

Shea turned to the others. “Now if this magic is

going to work, I’ll need a little room. Don't come

too near us while I’m spinning the spell, or you’ll be

apt to get caught in it, too.” He arranged a pair of

seats well back from the table and attached a thread

to the ring.

Laeg pushed Uath into one of the seats. “That’s a

bad geas you have there, Uath,” said Shea, “and I

want you to cooperate with me in getting rid of it.

You’ll do everything I tell you, won’t you?”

The man nodded. Shea lifted the ring, said,

“Watch this,” and began twirling the thread back

and forth between thumb and forefinger, so that the

ring rotated first one way and then the other,

sending out a flickering gleam of reflection from the

rushlights. Meanwhile Shea talked to Uath in a low

voice, saying “sleep” now and then in the process.

Behind him he could hear an occasionally caught

breath and could almost feel the atmosphere of

suspense.

Uath went rigid.

Shea asked in a low voice, “Can you hear me,

Uath?”

“That I can.”

“You will do what I say.”

“That I will.”

“When you wake up, you won’t suffer from this

howling geas any more.”

“That I will not.”

“To prove that you mean it, the first thing you do

on waking will be to clap Laeg on the shoulder.”

“That I will.”

Shea repeated his directions several times, varying

the words, and making Uath repeat them after him.

There was no use taking a chance on slipups. At least

he brought him out of the hypnotic trance with a

snap of the fingers and a sharp “Wake up!”

Uath stared about him with an air of bewilderment.

Then he got up, walked over to the table and

clapped Laeg on the shoulder. There was an

appreciative murmur from the audience.

Shea asked, “How do you feel, Uath?”

“It is just fine that I am feeling. I do not want to

be howling at the moon at all now, and I’m thinking

the geas is gone for good. I thank your honor.” He

came down the table, seized Shea’s hand and kissed

it and joined the other retainers at the lower part of

the table.

Cathbadh said, “That is a very good magic,

indeed, and not the least of it was the small geas you

put on him to lay his hand on Laeg’s shoulder at the

same time. And true it is that I have been unable to

lift this geas. But as one man can run faster, so can

another one climb faster, and I will demonstrate by

taking the geas off your wife, which you have

evidently not been able to deal with.”

“I’m not sure. . .” began Shea, doubtfully.

“Let not yourself be worried,” said Cuchulainn.

“It will not harm her at all, and in the future she can

be more courteous in the high houses she visits.”

The druid rose and pointed a long, bony finger at

Belphebe. He chanted some sort of rhythmic affair

which began in a gibberish of unknown language,

but became more and more intelligible, ending with:

“ . . . and by oak, ash and yew, by the beauty of

Aengus and the strength of Ler and by authority as

high druid of Ulstr, let this geas be lifted from you,

Belphebe! Let it pass! Out with it! It is erased,

cancelled and no more to be heard of!” He tossed up

his arms and then sat down. “How do you feel,

darling?”

“In good sooth, not much different than before,”

said Belphebe. “Should I?”

Cuchulainn said, ‘But how can we know now that

the spell has worked? Aha! I have it! Come with

me.” He rose and came round the table, and in

response to Shea’s exclamation of fury and

Belphebe’s of dismay, added, “Only as far as the

door. Have I not given you my word?”

He bent over Belphebe, put one arm around her

and reached for her hand, then reeled back,

clutching his stomach with both hands and gasping

for breath. Cathbadh and Laeg were on their feet.

So was Shea.

Cuchulainn staggered against Laeg’s arm, wiped a

sleeve cross his eyes and said, “Now the American is

the winner, since your removal spell has failed, and

it was like to be the death of me that the touch of her

was. Do you be trying it yourself, Cathbadh, dear.”

The druid reached out and laid a cautious finger

on Belphebe’s arm. Nothing happened.

Laeg said, “Did not the serf say that a magician

was proof against this geas?”

Cathbadh said, “You may have the right of it

there, although, but I am thinking myself there is another

reason. Cucuc wished to take her to his bed,

while I was not thinking of that at all, at all.”

Cuchulainn sat down again and addressed Shea.

“A good thing it is, indeed, that I was protected

from the work of this geas. Has it not proved

obstinate even to the druids of your own country?”

“Very,” said Shea. “I wish I could find someone

who could deal with it. "He had been more

surprised than Cuchulainn by the latter’s attack of

cramps, but in the interval he had figured it out.

Belphebe hadn’t had any geas on her in the first

place. Therefore, when Cathbadh threw at her a

spell designed to lift a geas, it took the opposite

effect of laying on her a very good geas indeed. That

was elementary magicology, and under the conditions

he was rather grateful to Cathbadh.

Cathbadh said, “In America there may be none to

deal with such a matter, but in Ireland there is a man

both bold and clever enough to lift the spell.”

“Who’s he?” asked Shea.

“That will be Ollgaeth of Cruachan, at the Court

of Ailill and Maev, who put the geas on Uath.”

Brodsky, from beside Shea spoke up. “He’s the

guy that’s going to put one on Cuchulainn before the

big mob takes him.”

“Wurra!” said Cathbadh to Shea. “Your slave

must have a second mind to go with his second sight.

The last time he spoke, it would only be a spell that

Ollgaeth would be putting on the Little Hound.”

“Listen, punk,” said Brodsky in a tone of exas

peration, “get the stones out of your head. This is

the pitch: this Maev and Ailill are mobbing up everybody

that owes Cuchulainn here a score, and when

they get them all together, they’re going to put a geas

on him that will make him fight them all at once,

and it’s too bad.”

Cathbadh combed his beard with his fingers. “If

this be true. . .” he began.

“It’s the McCoy. Think I’m on the con?”

“I was going to say that if it be true, it is high

tidings from a low source. Nor do I see precisely how

it may be dealt with. If it were a matter of spells only

. . ."

Cuchulainn said with mournful and slightly

alcoholic gravity, “I would fight them all without

the geas, but if I am fated to fall, then that is an end

of me.”

Cathbadh turned to Shea. “You see the trouble

we have with himself. Does your second sight reach

farther, slave?”

Brodsky said, “Okay, lug, you asked for it. After

Cuchulainn gets rubbed out, there’ll be a war and

practically everybody in the act gets knocked off,

including you and Ailill and Maev. How do you like

it?”

“As little as I like the look of your face,” said

Cathbadh. He addressed Shea. “Can this foretelling

be trusted?”

“I’ve never known him to be wrong.”

Cathbadh glanced from one to the other till one

could almost hear his brains rumbling. Then he said,

“I am thinking, Mac Shea, that you will be having

business at Ailill’s court.”

“What gives you such an idea?”

“You will be wanting to see Ollgaeth in this

matter of your wife’s geas, of course. A wife with a

geas like that is like one with a bad eye, and you can

never be happy until it is removed entirely. You will

take your man with you, and he will tell his tale and

let Maev know that we know of her schemings, and

they will be no more use than trying to feed a boar

on bracelets.”

Brodsky snapped his fingers and said, “Take him

up,” in a heavy whisper, but Shea said, “Look here,

I’m not at all sure that I want to go to Ailill’s court.

Why should I? And if this Maev is as determined as

she seems to be, I don’t think you’ll stop her by

telling her you know what she’s up to.”

“On the first point,” said the druid, “there is the

matter that Cucuc saved your life and all, and you

would be grateful to him, not to mention the geas.

And for the second, it is not so much Maev that I

would be letting know we see through her planning

as Ollgaeth. For he will know as well as yourself,

that if we learn of the geas before he lays it, all the

druids at Conchobar’s court will chant against him,

and he will have no more chance of making it bite

than a dog does of eating an apple.”

“Mmm,” said Shea. “Your point about gratitude

is a good one, even if I can’t quite see the validity

of the other. What we want mostly is to get to our

own home, though.” He stifled a yawn. “We can

take a night to sleep on it and decide in the morning.

Where do we sleep?”

“Finn will show you to a chamber,” said Cuchulainn.

“Myself and Cathbadh will be staying up the

while to discuss on this matter of Maev.” He smiled

his charming and melancholy smile.

Finn guided the couple to a guest-room at the

back of the building, handed Shea a rush-light and

closed the door, as Belphebe put up her arms to be

kissed.

The next second Shea was doubled up and

knocked flat to the floor by a super-edition of the

cramps.

Belphebe bent over him. “Are you hurt, Harold?”

she asked.

He pulled himself to a sitting posture with his

back against the wall. “Not — seriously,” he

gasped. “It’s that geas. It doesn’t take any time out

for husbands.”

The girl considered. “Could you not relieve me of

it as you did the one who howled?”

Shea said, “I can try, but I can pretty well tell in

advance that it won’t work. Your personality is too

tightly integrated — just the opposite of these hysterics

around here. That is, I wouldn’t stand a

chance of hypnotizing you.”

“You might do it by magic.”

Shea scrambled the rest of the way to his feet.

“Not till I know more. Haven’t you noticed I’ve

been getting an over-charge — first that stroke of

lightning and then the wine fountain? There’s something

in this continuum that seems to reverse my

kind of magic.”

She laughed a little. “If that’s the law, why there’s

an end. You have but to summon Pete and make a

magic that would call for us to stay here, then hey,

presto! we are returned.”

“I don’t dare take the chance, darling. It might

work and it might not — and even if it did, you’d be

apt to wind up in Ohio with that geas still on you,

and we really would be in trouble. We do take our

characteristics along with us when we make the

jump. And anyway, I don’t know how to get back to

Ohio yet.”

“What’s to be done, then?” the girl said. “For

surely you have a plan, as always.”

“I think the only thing we can do is take up Cathbadh’s

scheme and go see this Ollgaeth. At least, he

ought to be able to get rid of that geas.”

All the same, Shea had to sleep on the floor.

Synopsis

Fleeing Finland, Harold Shea, his wife Belphebe (late of

FAERIE QUEEN) and the indomitable Pete Brodsky find

themselves in Celtic Ireland instead of Ohio, arriving in a

downpour.

It is Pete’s knowledge of Ireland that saves them; a

lifetime of being around Irish cops, and trying to be one of

the boys, makes Brodsky invaluable.

Upon arrival, they are mistaken for Fomorians by the

‘Hound of Ulster, the legendary Cuchulainn himself.

However, they are set upon by Lagenians, and Cuchulainn

rescues them, being upset with them for ganging up.

Falling in with Cucuc, as they came to find he was called,

they set out for his camp. As usual, they claim to be

magicians, and ask to see the leading druid in Ireland.

To resist the amorous advances of Cucuc, Belphebe strips

naked in public, thereby violating a taboo, and driving

Cucuc from her. To explain her behavior, Pete improvises

the tale that she has a horrible geas laid on her that makes

any man that comes near her violently ill. This mollifies

Cucuc, but prompts the druid to attempt the lifting of the

bogus geas. In so doing, he inflicts a real one, and Shea is

even more bereft.

All his magic has failed dismally in Ireland; the return

spell attempt nearly fried them when it tracted lightning, his

water-to-wine spell nearly inundated the party at which he

tried it. He has impressed Cathbadh, the druid of Cucuc’s

faction, by removing a werewolf-like curse from a man with

some elementary hypnosis. When Cathbadh inadvertently

puts the bogus geas on Belphebe, he admits defeat, and tells

Shea that there is one other in Ireland that might be able to

help — Ollgaeth, chief druid to the Connachta, hereditary

enemies of Ulster.

Brodsky, with his knowledge of Celtic lore, has tried to

warn Cucuc that the Connachta will still try to do him

mischief. Cucuc is undismayed, and so the trio set out to

meet Ollgaeth to try once more to return to Ohio . . .

arold Shea. Bel-phoebe.

and Pete

arold Shea. Bel-phoebe.

and Pete

Brodsky rode steadily at a walk across the central

plain of Ireland, the Sheas on horses, Brodsky on a

mule which he sat with some discomfort, leading a

second mule carrying the provisions and equipment

that Cuchulainn had pressed on them. Their accouterments

included serviceable broadswords at the

hips of Shea and Brodsky and a neat dagger at Belphebe’s

belt. Her request for a bow had brought

forth only miserable sticks that pulled no farther

than the breast and were quite useless beyond a

range of fifty yards, and these she had refused.

All the first day they climbed slowly into the uplands

of Monaghan. They followed the winding

course of the Erne for some miles and splashed

across it at a ford, then struck the boglands of western

Cavan. Sometimes there was a road of sorts,

sometimes they plodded across grassy moors, following

the vague and verbose directions of peasants.

As they skirted patches of forest, deer started and

ran before them, and once a tongue-lolling wolf

trotted paralled to their track for a while before

abandoning the game.

By nightfall they had covered at least half their

journey. Brodsky, who had begun by feeling sorry

for himself, began to recover somewhat under the

ministrations of Belphebe’s excellent camp cookery,

and announced that he had seen quite enough of ancient

Ireland and was ready to go back.

“I don’t get it,” he said. “Why don’t you just

mooch off the way you came here?”

“Because I’m unskilled labor now,” explained

Shea.” You saw Cathbadh make that spell — he

started chanting in the archaic language and brought

it down to date. I get the picture, but I’d have to

learn the archaic. Unless I can get someone else to

send us back. And I’m worried about that. As you

said, we’ve got to work fast. What are you going to

tell them if they’ve started looking for you when we

get back?”

“Ah, nuts,” said Brodsky. “I’ll level with them.

The force is so loused up with harps that are always

cutting up touches about how hot Ireland is that

they’ll give it a play whether they believe me or not.”

Belphebe said in a small voice, “But I would be at

home.”

“I know, kid,” said Shea. “So would I. If I only

knew how.”

Morning showed mountains on the right, with a

round peak in the midst of them. The journey went

more slowly than on the previous day, principally

because all three had not developed riding callouses.

They pulled up that evening at the hut of a peasant

rather more prosperous than the rest, and Brodsky

more than paid for their food and lodging with tales

out of Celtic lore. The pseudo-Irishman certainly

had his uses.

The next day woke in rain, and though the peasant

assured them that Rath Cruachan was no more than

a couple hours’ ride distant, the group became involved

in fog and drizzle, so that it was not till afternoon

that they skirted Loch Key and came to Magh

Ai, the Plain of Livers. The cloaks with which Cuchulainn

had furnished them were of fine wool, but

all three were soaked and silent by time a group of

houses came into sight through air slightly clearing.

There were about as many of the buildings as

would constitute an incorporated village in their own

universe, surrounded by the usual stockade and wide

gate — unmistakably Cruachan of the Poets, the

capital of Connacht.

As they approached along an avenue of trees and

shrubbery, a boy of about thirteen, in shawl and kilt

and carrying a miniature spear, popped out of the

bushes and cried: “Stand there! Who is it you are

and where are you going?”

It might be important not to smile at this diminutive

warrior. Shea identified himself gravely and

asked in turn, “And who are you, sir?”

“I am Goistan mac Idha, of the boy troop of

Cruachan, and it is better not to interfere with me.”

Shea said, “We have come from a far country to

see your King and Queen and the druid Ollgaeth.”

He turned and waved his spear toward where a

building like that at Muirthemne, but more ornate,

loomed over the stockade, then marched ahead of

them down the road.

At the gate of the stockade was a pair of hairy

soldiers, but their spears were leaning against the

posts and they were too engrossed in a game of

knuckle-bones even to look up as the party rode

through. The clearing weather seemed to have

brought activity to the town. A number of people

were moving about, most of whom paused to stare

at Brodsky, who had flatly refused to discard the

pants of his brown business-suit and was evidently

not dressed for the occasion.

The big house was built of heavy oak beams and

had wooden shingles instead of the usual thatch.

Shea stared with interest at windows with real glass

in them, even though the panes were little diamondshaped

pieces half the size of a hand and far too irregular

to see through.

There was a doorkeeper with a beard badly in

need of trimming and lopsided to the right. Shea got

off his horse and advanced to him, saying, “I am

Mac Shea, a traveler from beyond the island of the

Fomorians, with my wife and bodyguard. May we

have an audience with their majesties, and their

great druid, Ollgaeth?”

The doorkeeper inspected the party with care and

then grinned. “I am thinking,” he said, “that your

honor will please the Queen with your looks, and

your lady will please himself, so you had best go

along in. But this ugly lump of a bodyguard will

please neither, and as they are very sensitive and this

is judgment day, he will no doubt be made a head

shorter for the coming, so he had best stay with your

mounts.”

Shea glanced round in time to see Brodsky replace

his expression of fury with the carefully cultivated

blank that policemen use, and helped Belphebe off

her horse.

Inside, the main hall stretched away with the usual

swords and spears in the usual place on the wall, and

a rack of heads, not as large as Cuchulainn’s. In the

middle of the hall, surrounded at a respectful distance

by retainers and armed soldiers, stood an

oaken dais, ornamented with strips of bronze and