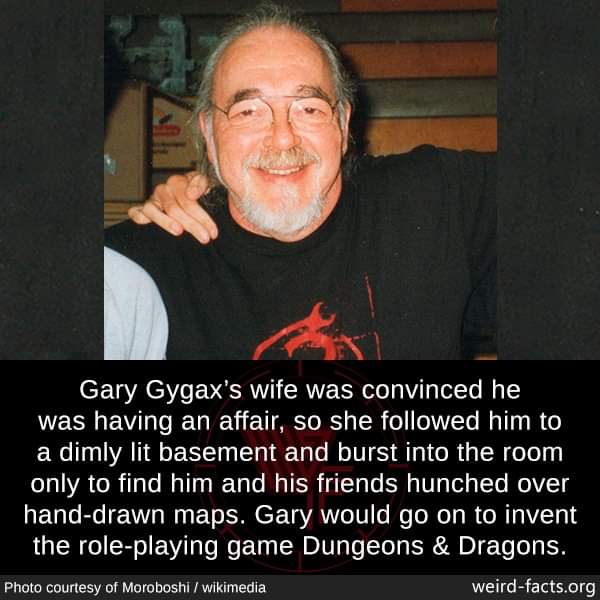

THE MELEE

IN D&D®

by Gary Gygax

| And a few additional words... | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon 24 | - | - | - | Dragon |

There is some controversy

regarding the system of resolving individual battles used in DUNGEONS

& DRAGONS and the somewhat

similar ADVANCED

DUNGEONS & DRAGONS melee system. The

meat of D&D is the concept

of pure adventure, the challenge of the unknown, facing the unexpected

and overcoming all obstacles. At times

this requires combat with

spell, missile, and hand-to-hand fighting.

How crucial to the game

as a whole is the melee? What part should it

play? Is “realism” an important

consideration?

To put the whole matter into

prespective, it is necessary to point out that there is probably

only a small percentage

of the whole concerned with possible shortcomings in the melee system,

but even 1% to perhaps 5% of an audience of well over 100,000 enthusiasts

is too large a number to be

totally ignored. To the

majority who do not have problems with the rationale of fantasy melee as

presented in D&D, what follows will serve

to strengthen your understanding

of the processes and their relationship to the whole game. For those who

doubt the validity of D&D combat systems, the expostulation will at

least demonstrate the logic of the

systems, and perhaps justify

them to the extent that you will be able to

use them with complete assurance

that they are faithful representations of the combat potential of the figures

concerned.

There can be no question

as to the central theme of the game. It is

the creation and development

of the game persona, the fantastic

player character who is

to interact with his of her environment —

hopefully to develop into

a commanding figure in the milieu. In order

to do so, the player character

must undergo a continuing series of activities which are dictated by the

campaign at large and the Dungeon

Master in particular. Interaction

can be the mundane affairs of food,

equipment and shelter, or

it can be dealing with non-player characters

in only slightly less routine

things such as hiring of men-at-arms, treating with local officials, and

so on. But from even these everyday affairs

can develop adventures,

and adventurers are, of course, the meat of

D&D; for it is by means

of adventuring that player characters gain

acumen and the wealth and

wherewithal to increase in ability level.

The experience, actual and

that awarded by the DM, is gained in the

course of successive adventures,

and it is most common to engage in

combat.

Hacking and slewing should

not, of course, be the first refuge of

the beleaguered D&Der,

let alone his or her initial resort when confronted with a problem situation.

Naturally enough, a well run campaign will offer a sufficient number of

alternatives as well as situations

which encourage thinking,

negotiation, and alternatives to physical

force, by means of careful

prompting or object lessons in the negative

form. Aside from this, however,

combat and melee will certainly occupy a considerable amount of time during

any given adventure, at

least on the average. Spell

and missile combat do not consume any appreciable amount of time, but as

they are also often a part of an overall

melee, these factors must

be considered along with hand-to-hand

fighting.

What must be simulated in

melee combat are the thrusts and

blows (smashing and cutting)

of weapons wielded as well as natural

body weaponry of monsters

— teeth, claws, and so forth. Individual

combat of this sort can

be made exceptionally detailed by inclusion of

such factors as armor, weapon(s),

reflex speed, agility, position of

weapon (left or right hand

or both), training, strength, height, weight,

tactics chosen (attack,

defend, or in a combination), location of successful blows, and results

of injury to specific areas. If, in fact, D&D

were a game of simulation

of hand-to-hand combat utilizing miniature

figurines, such detail would

be highly desirable. The game is one of

adventure, though, and combats

of protected nature (several hours

minimum of six or more player

characters are considered involved

against one or more opponents

each) are undesirable, as the majority

of participants are most

definitely not miniature battle game enthusiasts. Time could be reduced

considerably by the inclusion of such

factors as death blows —

a kill at a single stroke, exceptionally high

amounts of damage — a modified

form of killing at a single stroke,

specific hit location coupled

with specific body hit points, and special

results from hits — unconsciousness,

loss of member, incapacitation

of member, etc.

Close simulation of actual

hand-to-hand combat and inclusion of

immediate result strokes

have overall disadvantages from the standpoint of the game as a whole.

Obviously, much of the excitement and

action is not found in melee,

and even excitement and action is not

found in melee, and even

shortening the process by adding in death

strokes and the like causes

undue emphasis on such combat. Furthermore, D&D is a role playing campaign

game where much of the real

enjoyment comes for participants

from the gradual development of

the game personae, their

gradual development, and their continuing

exploits (whether successes

or failures). In a system already fraught

with numberless possibilities

of instant death — spells, poison, breath

and gaze weapons, and traps

— it is too much to force players to face

yet another. Melee combat

is nearly certain to be a part of each and

sibility of character death

highly likely, but it also allows the wise to

withdraw if things get too

tough — most of the time in any case.

The D&D combat systems

are not all that “unrealistic” either, as

will be discussed hereafter.

The systems are designed to provide

relative speed of resolution

without either bogging the referee in a

morass of paperwork or giving

high probability of death to participants’ personae. Certainly, the longer

and more involved the melee

procedure, the more work

and boredom from the Dungeon Master,

while fast systems are fun

but deadly to player characters (if such

systems are challenging

and equitable) and tend to discourage participants from long term committment

to a campaign, for they cannot

relate to a world in which

they are but the briefest of candles, so to

speak.

In order to minutely examine

the D&D combat system as used in

the ADVANCED game, an example

of play is appropriate. Consider a

party of adventurers treking

through a dungeon’s 10’ wide corridor

when they come upon a chamber

housing a troop of gnoll guards. Let

us assume that our party

of adventurers is both well-balanced in

character race and class.

They have a dwarf, gnome, and halfling in

the front rank. Behind them

are two half-elves. The last rank consists

of three humans. Although

there are eight characters, all of them are

able to take an active part

in the coming engagement; spells and

missiles can be discharged

from the rear or middle rows. The center

rank characters will also

be able to engage in hand-to-hand combat if

they have equipped themselves

with spears or thrusting pole arms

which are of size useful

in the surroundings. The front rank can initially use spells or missiles

and then engage in melee with middle rank support, assuming that the party

was not surprised. Whether or not any

exchange of missiles and

spells takes place is immaterial to the example, for it is melee which

is the activity in question. Let us then move on

to where the adventurers

are locked in combat with the gnolls.

Each melee round is considered

to be a one minute time period,

with a further division

into ten segments of six seconds each for determination of missile fire,

spell casting and the striking of multiple telling blows. Note that during

the course of a round there are assumed to

be numbers of parries, feints,

and non-telling attacks made by opponents. The one (or several) dice roll

(or rolls) made for each adversary, however, determines if a telling attack

is made. If there is a hit indicated, some damage has been done; if a miss

is rolled, then the opponent managed to block or avoid the attack.

If the participants picture

the melee as somewhat analogous

to a boxing match they will have a

correct grasp of the rationale

used in designing the melee system. During the course of a melee round

there is movement, there are many attacks which do not score, and each

“to hit” dice roll indicates that

there is an opening which

may or may not allow a telling attack. In a recent letter, Don Turnbull

stated that he envisioned that three sorts of

attacks were continually

taking place during melee:

1) attacks which had no chance of hitting, including feints, parries, and the like;

2) attacks which had a chance

of doing damage but which

missed as indicated by the

die roll; and

3) attacks which were telling

as indicated by the dice roll and

subsequent damage determination.

This is a correct summation

of what the D&D melee procedure

subsumes. Note that the

skill factor of higher level of higher

levelfighters — as well

as natural abilities and/or speed of some

monsters — allows more than

one opportunity per melee round of

scoring a telling attack

as they are more able to take advantage of

openings left by adversaries

during the course of sparring. Similarly,

zero level men, and monsters

under one full hit die, are considered as

being less able to defend;

thus, opponents of two of more levels of hit

dice are able to get in

one telling blow for each such level or hit die.

This melee system also hinges

on the number of hit points assigned to characters. As I have repeatedly

pointed out, if a rhino can

take a maximum amount of

damage equal to eight of nine eight-sided

dice, a maximum of 64 or

72 hit points of damage to kill, it is positively

absurd to assume that an

8th level fighter with average scores on his or

her hit dice and an 18 consititution,

thus having 76 hit points, can

physically withstand more

punishment than a rhino before being

killed. Hit points are a

combination of actual physical consititution,

skill at the avoidance of

taking real physical damage, luck and/or

magical or divine factors.

Ten points of damage dealt to a rhino indicated a considerable wound, while

the same damage sustained by the

8th level fighter indicates

a near miss, a slight wound, and a bit of luck

used up, a bit of fatigue

piling up against his or her skill at avoiding the

fatal cut or thrust. So

even when a hit is scored in melee combat, it is

more often than not a grazing

blow, a scratch, a mere light wound

which would have been fatal

(or nearly so) to a lesser mortal. If sufficient numbers of such wounds

accrue to the character, however,

stamina, skill, and luck

will eventually run out, and an attack will

strike home . . .

I am firmly convinced that

this system is superior to all others so

far concieved and published.

It reflects actual combat reasonably, for

weaponry, armor (protection

and speed and magical factors), skill

level, and allows for a

limited amount of choice as to attacking or

defending. It does not require

participants to keep track of more than

a minimal amount of information,

it is quite fast, and it does not place

undue burden upon the Dungeon

Master. It allows those involved in

combat to opt to retire

if they are taking too much damage — although

this does not necessarily

guarantee that they will succeed or that the

opponents will not strike

a telling blow prior to such retreat. Means of

dealing fatal damage at

a single stroke or melee routine are kept to a

minimum commensurate with

the excitement level of the system.

Poison, weapons which deliver

a fatal blow, etc. are rare or obvious.

Thus, participants know

that a giant snake or scorpion can fell with a

single strike with poison,

a dragon or a 12 headed hydra or a cloud

giant deliver considerable

amounts of damage when they succeed in

striking, and they also

are aware that it is quite unlikely that an opponent will have a sword

of sharpness, a vorpal blade, or some similar

deadly weapon. Melee, then,

albeit a common enough occurrence, is a

calculated risk which participants

can usually determine before engaging in as to their likelihood of success;

and even if the hazards are

found to be too severe,

they can often retract their characters to fight

again another day.

Of course, everyone will

not be satisfied with the D&D combat

system. If DM and players

desire a more complex and time consuming

method of determining melee

combat, or if they wish a more detailed

but shorter system, who

can say them nay.

However, care must be

taken to make certain that

the net effect is the same as if the correct

system had been employed,

or else the melee will become imbalanced.

If combat is distorted to

favor the player characters, experience levels

will rise too rapidly, and

participants will become bored with a game

which offers no real challenge

and whose results are always a foregone

conclusion. If melee is

changed to favor the adversaries of player

characters, such as by inclusion

of extra or special damage when a high

number is rolled on a “to

hit” die, the net results will also be a loss of

interest in the campaign.

How does a double damage on a die score of

20 favor monsters and spoil

a campaign? you ask. If only players are

allowed such extra damage,

then the former case of imbalance in favor

of the players over their

adversaries is in effect. If monsters are allowed

such a benefit, it means

that the chances of surviving a melee, or withdrawing from combat if things

are not going well, are sharply reduced.

That means that character

survival will be less likely. If players cannot

develop and identify with

a long lived character, they will lose interest

in the game. Terry Kuntz

developed a system which allowed for telling

strokes in an unpublished

game he developed to recreate the epic

adventures of Robin Hood

etal. To mitigate against the loss at a single

stroke, he also included

a saving throw which allowed avoidance of

such death blows, and saving

throw increased as the character successfully engaged in combats, i.e.

gained experience. This sort of approach

is obviously possible, but

it requires a highly competent designer to

develop.

Melee in D&D is certainly

a crucial factor, and it must not be

warped at risk of spoiling

the whole game. Likewise, it is not unrealistic — if there is such a thing

as “realism” in a game, particularly a

game filled with the unreal

assumptions of dragons, magic spells, and

so on. The D&D melee

combat system subsumes all sorts of variable

factors in a system which

must deal with imaginary monsters, magicendowed weaponry, and make-believe

characters and abilities. It does

so in the form as to allow

referees to handle the affair as rapidly as possible, while keeping balance

between player characters and opponents,

and still allowing the players

the chance of withdrawing their

characters if the going

gets too rough. As melee combat is so common

an occurrence during the

course of each adventure, brevity, equitability, and options must be carefully

balanced.

Someone recently asked how

I could include a rule regarding

weapons proficiency in the

ADVANCED game after decrying what

they viewed as a similar

system, bonuses for expertise with weapons.

The AD&D system, in

fact, penalizes characters using weapons which

they do not have expertise

with. Obviously, this is entirely different in

effect upon combat. Penalties

do not change balance between

character and adversary,

for the player can always opt to use nonpenalized weapons for his or her

character.

It also makes the game

more challenging by further

defining differences in character classes

and causing certain weapons

to be more desirable, i.e. will the magic

hammer + 1 be useful to

the cleric? It likewise adds choices. All this

rather than offering still

another method whereby characters can more

easily defeat opponents

and have less challenge. How can one be mistaken as a variation of the

other? The answer there is that the results of

the two systems were not

reflected upon. With a more perfect

understanding of the combat

system and its purposes, the inquirer will

certainly be able to reason

the thing through without difficulty and

avoid spoiling the game

in the name of "realism."

Realism does have a function

in D&D, of course. It is the tool of

the DM when confronted with

a situation which is not covered by the

rules. With the number of

variables involved in a game such as D&D,

there is no possibility

of avoiding situations which are not spelled out

in the book. The spirit

of the rules can be used as a guideline, as can the

overall aim of rules which

apply to general cases, but when a specific

situation arises, judgement

must often be brought into play.

Sean

Cleary pointed this out

to me in a letter commenting on common misunderstandings and difficulties

encountered by the DM. While the

ADVANCED system will make

it absolutely clear that clerics, for example, have but one chance to attempt

to turn undead, and that there

is no saving throw for those

struck by undead (life level is drained!),

there is no possibility

of including minutia in the rules. To illustrate

further, consider the example

of missile fire into a melee. Generally,

the chances of hitting a

friend instead of a foe is the ratio of the two in

the melee. With small foes,

the ratio is adjusted accordingly, i.e. two

humans fighting four kobolds

gives about equal probabilities of hitting either. Huge foes make it almost

impossible to strike a friend, i.e.

aiming at a 12’ tall giant’s

upper torso is quite unlikely to endanger the

6’ tall human of a javelin

of lightning bolts into a melee where a

human and a giant are engaged.

The missile strikes the giant; where

does its stroke of lightning

travel? Common sense and reality indicate

that the angle of the javelin

when it struck the giant will dictate that the

stroke will travel in a straight

line back along the shaft, and the rest is a

matter of typical positions

and angles — if the human was generally

before the giant, and the

javelin was thrown from behind the human,

the trajectory of the missile

will be a relatively straight line ending in

the shaft of the weapon

and indicating the course of the bolt of lightening backwards. The giant’s

human opponent will not be struck by the

stroke, but the lightning

will come close most probably. Therefore, if

the human is in metal armor

a saving throw should be made to determine if he or she takes half or no

damage.

In like manner, reality can

illustrate probabilities. If three husky

players are placed shoulder

to shoulder, distances added for armor,

and additional spaces added

for weapon play, the DM can estimate

what activities can take

place in a given amount of space. Determination of how many persons can

pass through a door 5’ wide can be

made with relative ease

— two carefully, but if two or three rush to

pass through at the same

time a momentary jam can occur. How long

should the jam last? How

long would people actually remain so

wedged? With an added factor

for inflexible pieces of plate mail, the

answer is probably one OF

two segments of a round. Of course, during

this period the jammed characters

cannot attack or defend, so no

shield protection or dexterity

bonus to armor class would apply, and

an arbitrary bonus of +

4 could be given to any attackers (an arbitrary

penalty of -4 on saving

throws follows).

The melee systems used in

D&D are by no means sacrosanct.

Changes can be made if they

are done intelligently by a knowledgeable

individual who thoroughly

understands the whole design. Similarly,

“realism” is a part of melee,

for the DM must refer to it continually to

ajudicate combat situations

where no rules exist, and this handling is

of utmost importance in

maintaining a balanced melee procedure.

With this truly important

input from the referee, it is my firm belief

that the D&D system

of combat is not only adequate but actually unsurpassed by any of its rival’s

so-called “improvements” and

“realistic” methods. The

latter add complication, unnecessary record

keeping, or otherwise distort

the aim of a role playing game —

character survival and identification.

What is foisted off on the gullible is typically a hodge-podge of arbitrary

rulings which are claimed to

give “realism” to a make-believe

game. Within the scope of the whole

game surrounding such systems,

they might, or might not, work well

enough, but seldom will

these systems fit into D&D regardless of the

engineering attempts of

well-meaning referees.

The logic of the D&D

melee systems is simple: They reasonably

reflect fantastic combat

and they work damn well from all standpoints. My advice is to leave well

enough alone and accept the game for

what it is. If you must

have more detail in melee, switch to another

game, for the combat portions

of D&D are integral and unsuccessful

attempts to change melee

will result in spoiling the whole. Better to

start fresh than to find

that much time and effort has been wasted on a

dead end variant.

AND A FEW ADDITIONAL

WORDS . . .

Those of you who read the

first article in this series (“Dungeons &

Dragons,

What It ls And Where It Is Going,” DRAGON #22) will appreciate knowing

that TSR is now in the process of creating its Design

Department. Jean Wells is

now on the staff in order to give the game

material with a feminine

viewpoint — after all, at least 10% of the

players are female! Lawrence

Shick also joined us recently, and he will

work primarily with science

fantasy and science fiction role playing adventure game material, although

you’ll undoubtedly be seeing his

name on regular D&D/AD&D

items as well. In the coming months I

envision the addition of

yet more creative folks, and as new members

are added to our staff,

you’ll read about it here. What TSR aims to do is

to assure you that you get

absolutely the finest in adventure gaming

regardless of the form it

is in; and the new Design Department will answer your questions, handle

the review of material submitted for possible publication by TSR, appear

at conventions, design tournaments,

author material for this

publication (and probably for other vehicles as

well), and create or assist

with the creation of playing aids and new

forms of adventure games.

This is a big order, certainly, but both Jean

and Lawrence are talented

and creative gamers. Expect great things

from them, and the others

who will join them soon, in the months to

come!