I’d like to be under the sea,

in an octopus’s garden, in the shade.

-The Beatles

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon | - | - | - | Dragon 48 |

In D&D® Supplement II, Blackmoor, and in the AD&D™ Dungeon

Masters Guide, much information is given on undersea

adventure. This article will address some of the more often

overlooked aspects of an undersea fantasy sub-campaign.

The first and most obvious problem is simply stated: Mammals do not

breathe water. The game offers many ways around

this problem, such as potions of water breathing, Magic-users’

spells, and other magic items that allow underwater activity. The

reverse problem is less troublesome: Mermen may leave the

water for brief periods, and the loathsome sahuagin (known as

“sags” to their many enemies) actually storm ashore on dark

nights to sack villages. One would assume that some hardier

individuals of each of those races might brave heat enough to

work iron, in coastal smithies or on small islands. (Perhaps with

an apprentice to douse the scaly smith with buckets of cold sea

water. There are, however, objections to sea folk using worked

iron at all, which will be discussed later in this article.) The

general rule of respiration seems to be that intelligent seacreatures

can breathe air for a little while, but one good lungful

of water will do in a human.

This leads one to wonder why there are any coastal airbreathers’ villages

at all. If the sea-folk and their monstrous pets

can wade in on a dark night and butcher a hamlet, and if the

land-folk cannot retaliate in kind, why wouldn’t the humans

eventually give up, go inland, and raise beets?

The answer, of course, is the land-folks’ superior technology.

While there just might be a few iron-working mermen, the overall tech

level of the sea-folk is probably equivalent to man’s late

Neolithic period (at the end of the Stone Age). They may have

crossbows, tridents, nets, shields, superior night vision, and

probably tactical surprise, but they don’t have fire, siege artillery,

and horses. Above all, sea-folk on land are hampered by

the painfully dry air, by gravity, and by restricted terrain. They

must also overcome ditches, walls, and other earthworks, all of

which are alien to their three-dimensional way of thinking. If a

merman can feel claustrophobia, an attack on a human village

must surely provoke it.

The mermen would succeed anyway if the village was small,

so presumably coastal villages are large and well fortified unless

a distinct truce or alliance exists between land dwellers and

sea-folk.

The advantages of such alliances are obvious (the mermen

run the fishing industry while the airbreathers provide trade

items, material and ideas—books cannot be preserved underwater; besides,

most mermen are illiterate.) One must assume

double villages exist in many areas — communities side by side,

where mermen and landsmen cooperate for mutual profit.

The earlier estimate of merman as no farther advanced than

the late Neolithic needs amplification. I assume that flint for

tools is available undersea (in sea cliffs, crags, and caves).

Bone, whale bone, sinews and skins are plentiful. Would the

sea-folk trade pearls or amber for steel knives? Would they even,

as postulated earlier, forge their own?

Probably not. Aside from the fact that steel rusts rapidly in the

ion-charged salt water, metal utensils are not as good for the

merman’s purpose as are flint ones. It has been demonstrated

repeatedly that a man can skin a buffalo quite a bit faster with a

good flint knife than with a steel one. The same would apply to a

shark, walrus, or water buffalo.

The flint knives of the human Neolithic are unparalleled for

edge, durability, efficiency, and beauty. Modern experimenters

must practice for years to produce a good, neo-Neolithic leafpoint.

Can the mermen be expected to do as well? No; they can

be expected to do better. Water has a strange effect upon brittle

solids: when immersed, such solids resist shattering. It is possible

to cut a piece of glass underwater with shears, a procedure

impossible in air. The piles of ruined spear-points that archaeologists

have found throughout Europe would be unknown

to the mermen. Their spear-points, arrowheads, and knives

would have a symmetry, beauty, and functional delicacy not

achieved by human flint-workers.

Mermen’s weapons include spears, tridents, the “speciallymade crossbow”

mentioned in Blackmoor and the DMG, and

some specialized weapons suited to underwater work. A net,

especially if set with dozens of small hooks, presents a formidably

entangling defensive weapon. Noisemakers can be used

against the sahuagin, damaging their supersensitive underwater hearing.

(Indeed, the hearing of all creatures underwater is

less acute, because sound travels through water more easily

than through air; mermen on land would seem rather deaf.)

Throwing daggers are replaced by streamlined darts, the caltrop by the

net, and the axe by a fan-shaped implement with the

blade thrust forward on a pole. Pole-arms in general are preferred

to swung weapons because of the water’s resistance

against something swung through it. Grappling hooks are

common, for slowing as well as wounding targets. Sacs of ink

can be used for smoke screens, and bladders of acid or poison

can be released down-current to injure the enemy.

Transport is said to be by the ubiquitous sea-horse, or hippocampus.

Aside from its poetic ludicrousness, the scheme is

unworkable, silly, and should be laughed at by anyone studying

the situation carefully. Carrying burdens, however, by means of

pack-dolphins, makes more sense, as does the use of dolphins

as towing engines to help speed a journey.

The D&D books suggest that mermen herd fish, and keep

these herds in pens. This strikes me as implausible. (Alas, Gary

Gygax is correct: I can easily swallow the “whale” of mermen,

underwater cities, and sunken civilizations, but must choke

upon the “minnow” of submarine agriculture. “Realism” in these

terms is meaningless... Where was I? Oh, yes...implausible).

Since “big fish eat little fish, and bigger fish eat them,” keeping

a

herd of groupers involves catching ten times their weight in

angelfish daily. It’s a heck of a lot easier to just catch the groupers

in the first place. This may be one of the reasons the American Indians

hunted buffalo rather than domesticating them.

Feeding those “thunder cattle” would have been prohibitively

difficult. When one adds the problems of taming them, calving

them, leading them to water, etc., it makes a lot more sense to

battle them than to breed them.

The mermen must fight sharks, sahuagin, giant crabs, and

other nasties constantly. In combat, assuming their backs are to

the sea floor, they are still vulnerable from a full hostile hemisphere.

If they are caught in mid-sea, they can be attacked from

any angle (although I believe that if the floor is unavailable,

they’d hug the surface). With the heightened mobility that the

ocean provides, all battles become encirclements of a smaller

force by a larger one. If the smaller force cannot penetrate a

weak spot and break through, there can be no retreat. Even a

larger and stronger force, if individually slower, is in deep trouble.

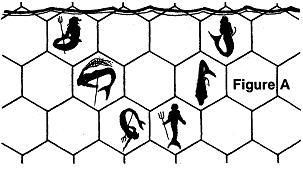

The immediate problem becomes: how do we simulate such a

combat? The tactical game maps of SPl’s Battlefleet Mars and

Vector Three are tempting, but not totally suitable. The best

solution I’ve yet found, and one that space-wargame designers

have long used, is to put the battle on a two-dimensional map,

with abstract rules to simulate the feel of the “real” situation.

As an example, consider the case of 100 sharks facing 70

mermen. To keep the numbers reasonable, I’ll use five-being

counters; thus, 20 shark counters face 14 mermen counters. In

D&D terms, the sharks move 24” (let each inch equal 10 yards, to

match the standard D&D outdoor combat scale); the mermen

move 18”. Assume that the mermen are defending against the

ocean’s surface, while the sharks attack from below. Further

assume that 5 mermen or sharks can effectively fight and control a

100-square-yard area.

A slice through the side view of a standard hemispherical

defense would appear as in Figure A, where each hex is roughly

(Turn to page 84)

10 yards across. The illustration is only a cross-section; of the 14

counters in the defense, only six show, the rest being in front of

or behind the hex sheet, to fill out a three-dimensional hemisphere.

There are no “stacking” rules, and no “zone-of-control”

inhibitions. In this situation the sharks move 24 hexes per turn

and the mermen 18.

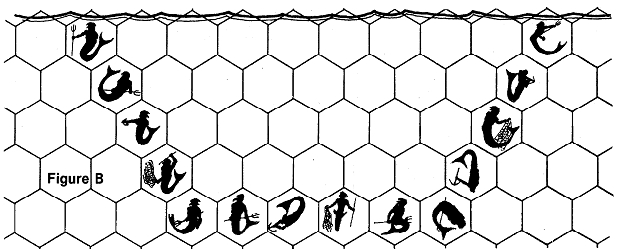

Figure B represents the two-dimensional analogue of the

same situation. Here, the linear frontage of each unit is a confused

mixture of area and length, and each hex measures

somewhere between 10 and 100 yards across. There is no movement “above”

or “below” the hex map; the situation is strictly

two-dimensional. Here, each shark counter moves 48 hexes per

turn (double the normal due to the distortion of the game-map);

each merman counter moves 36 hexes. These numbers arbitrarily may be

reduced to keep the combat on a normal-sized map, as

long as the sharks’ movement advantage is maintained in the

proper proportion.

Although distorted, Figure B nevertheless retains many of the

topological properties of Figure A. In both cases, all 14 mermen

counters face most of the 20 shark counters (not depicted), not

all of whom can attack at present. Until some of their comrades

die, there will be a few sharks left out of the battle for lack of

“elbow room.” The artificial restriction of the battle to a flat

board has virtually no effect upon the battle.

-

If the distortion is too appalling to the reader’s sense of naturalism,

some other method should be tried. This is the only

system I’ve yet found for such battles that worked well. In this

particular case, true three-dimensional simulation would be almost

as out of place as it would be in GDW’s Imperium.

Finally, two very minor points. First, why must the Giant Octopus always

be cast as the Bad Guy? Octopi are quite rational

beings, reacting coolly and logically to threats and to meal

opportunities. They are far less “evil” than wolves, tigers, or

jaguars; they are constitutionally incapable of any sort of angry

maliciousness.

Second, as anyone who has studied marine biology knows,

99% of all sea life is either on the continental shelves or floating

in the top three feet of the sea. The murky depths, although

sporting various peculiar high-pressure beasties, are relatively

barren. The mer-folk, swimming happily in the shallow, warm,

light blue water, think of these frigid, tenebrous depths much as

land-folk think of caves, pits, and mines: The dark unknown is

frightening — the home of devils and monsters. When crossing

deep places, mermen hug the surface of the water, just as humans cluster

about their torches when spelunking. At such times,

the superstitious fears of the two races are very nearly identical.

And just as humans nearly always bury their dead, sometimes

in caves and crypts, so do the mer-folk consign their dead to the

deeps. Wrapped in non-deteriorating shrouds, weighted with

great stones, the deceased are carried out to sea and dropped,

amid touching ceremonies, into the deepest part of the ocean.

Sea-folk most certainly do NOT eat their dead, such as has

been suggested in some works of literature — most lately a tale

entitled The Merman’s Children by Poul Anderson. It was

a nice

story, and in some parts quite factual, but in this respect it goes

just a little too far.

Best Fishes...