D&D®,

AD&D®

AND GAMING

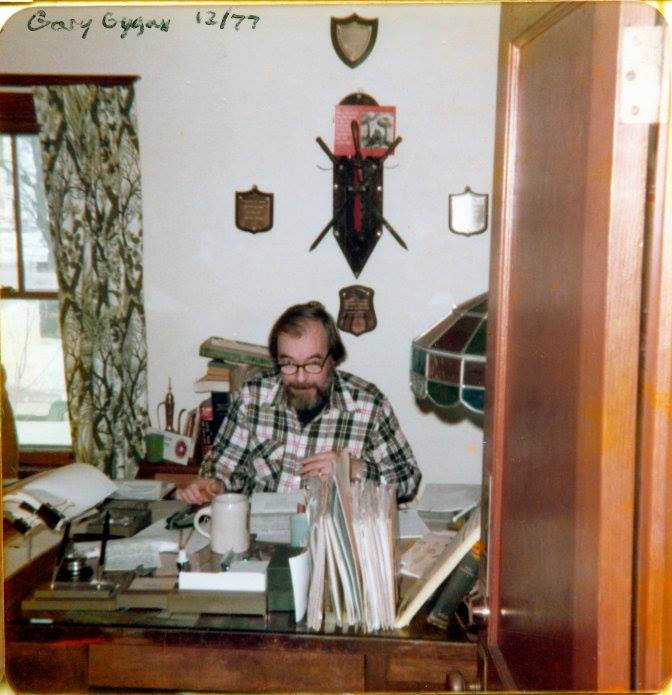

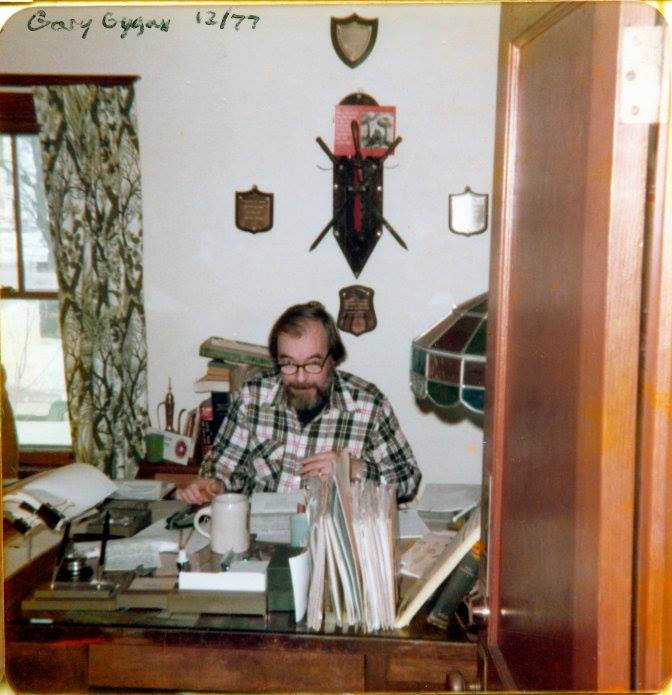

by ©Gary Gygax

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon 26 | - | - | - | Dragon |

Adventures of the cerebral

type have been with us for as long as

mankind has told tales around

campfires. Role playing is at least as old

as this too, if one considers

early religious or quasi-religious rites. Both

advanced in form during

the Golden Age of Greece, assuming forms

which are close to those

of today. How modem-era adventure games

came into being is connected

to all of this, for they owe their existence to

D&D, a fact which cannot

be disputed.

Fantasy wargaming began

before adventure gaming.

In fact it began before CHAINMAIL. Tony

Bath of England was conducting

table top battles roughly based on the

“Hyborean Age” of Robert

E. Howard’s Conan years before the “Fantasy Supplement” of CHAINMAIL was

published.

Similarly, role playing

has been common in wargaming for years—decades, I suspect,

when one considers the length

of time that hobby has been pursued in

England. I can personally

recall being part of the nationwide game

which was conceived by “The

AdHoc Committee for the Re-Reinstitution of WWII”.

The group was based in Stanford

University, and this

writer was given the role

of the Chinese Communist commander, while

my friend, Don Kaye, was

the Chinese Nationalist leader, and our

associate, Terry Stafford

of Chicago, was the British Far East Squadron

Commander. Interesting and

differing roles, but all involving thousands,

or millions, of men to be

commanded.

Our own local group, the

Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association,

became involved in one-to-one

gaming about 1970. Mike Reese and

Leon Tucker, both strong

proponents of WWII miniatures gaming, and

Jeff Perren and I with our

medieval miniatures, provided the group with

many hours of enjoyment

around the large sand table which reposed in

the basement of my home.

At various times our number commanded a

squad or more infantry,

bands of marauding Vikings, a key bunker, a

troop of Mongolian light

horse, a platoon of AFVs, and so on. Some of

these roles lasted for a

single game or two, some included large scale

map movement and the many

engagements which constitute a campaign.

Late in 1972 these roles

were extended to include superheroes

and wizards, as the special

fantasy section of what was to become

CHAINMAIL was play-tested.

Magic-users defended their strongholds

from invading armies, heroes

met trolls, and magic items of great power

were sought for on the same

sand table which had formerly hosted

Normans, Britain English

and tanks in Normandy. These games were

certainly adventures, and

role playing was involved, yet what was

played could by no means

be called either D&D or adventure gaming.

When Dave Ameson, already

a member of the International Federation of Wargaming, joined the Castle

& Crusade Society, he began

playing in our loosely organized

campaign game. Now most of the

action therein was conducted

by the LGTSA, using my sand table, other

members of the society coming

for visits to my place to join in from time

to time. Dave had a large

group in the Twin Cities, and they desired to

do their own thing. Dave,

an expert at running campaign games, began

to develop his own "Fief"

as a setting for medieval fantasy campaign

gaming, reporting these

games to the head of the C&C Society.

Using

CHAINMAIL’s “Fantasy Supplement”

and the “Man-To-Man” rules of

the same work, Dave made

some interesting innovations: First, he gave

his fellows more or less

individual roles to play—after all, “Blackmoor”

was just a small section

bordering on the “Great Kingdom”, and there

weren’t all that many heroes

and wizards and men-at-arms to parcel

out. Then, Dave decided

that he would allow progression of expertise

for his players, success

in games meaning that the hero would gain the

ability of five, rather

than but four men, eventually gaining the exaulted

status of superhero; similarly,

wizards would gain more spells if they

proved successful in their

endeavors. Lastly, following CHAINMAIL’s

advice to use paper and

pencil for underground activity such as mining

during campaign game sieges,

and taking a page out of the works of

Howard and Burroughs etal,

he brought the focus of fantasy miniatures

play to the dungeon setting.

CHAINMAIL had proved to be

highly successful primarily due to its

pioneering concepts in fantasy

and individual gaming concepts—the tail

end of the work which wagged

the rest. Dave Arneson expanded upon

these areas, and when he

and I got together, the ideas necessary to

create D&D were engendered.

After a brief visit, Dave returned home,

and within a few days I

had a copy of his campaign notes. A few weeks of

play-testing swelled the

ranks of the LGTSA to a score or more of avid

players, and the form of

D&D began to take shape.

If you ever meet

someone who claims to have

played the game since 1973, you can

believe him or her, for

by the spring of that year I had completed the

manuscript for the “Original”

version of D&D, and copies were handed

out but in order to stop

the late night and early morning phone calls

asking weird questions about

clerics or monsters or whatever.

By the Time DUNGEONS &

DRAGONS was published (January,

1974) there were already

hundreds of players, and the major parts of

what was to become GREYHAWK

were written and in use too.

Adventures, role playing,

games, and fantasy all reach back into the dawn of

history. Adventure gaming

dates only to 1973-74 and D&D. In 1974

only slightly more than

1,000 copies of the game had been sold. Today

far more than that are sold

each month. D&D has many competitors,

and every manufacturer of

miniature figures offers a wide range of

fantasy figures. Ads in

gaming and hobby trade publications stress

fantasy games and figures

more often than any other subject Adventure

gaming has come a long way,

and D&D began it all.

D&D is the leading adventure

game, it is the most influential, and the

most imitated. Since its

inception it has been added to through special

supplemental works (GREYHAWK,

BLACKMOOR,

ELDRITCH WIZARDRY, and GODS, DEMI-GODS & HEROES), augmented by miniatures

rules (SWORDS & SPELLS), and complimented by a host of specially approved

and licensed products from firms such as Judges

Guild and Miniature Figurines.

D&D has been edited (by the eminent J.

Eric Holmes) to provide

an introductory package, and the contents of

that offering have recently

been expanded to include a beginning

module. Despite all of this

activity, the game has remained pretty much

as it was when it was first

introduced in 1974, although there is now far

more to it.

ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS

is a different game. Readers please take note! It is neither an

expansion nor a revision of the old

game, it is a new game.

A number of letters have come to me, the writers

expressing their surprise

at or voicing their disapproval of this fact. John

Mansfield, in SIGNAL, cautions

his readers to be aware that an ongoing

D&D campaign cannot

be switched to AD&D without major work or

actual scrapping of the

old game and beginning a fresh effort. To

prevent any further misunderstandings,

it is necessary that all adventure

gaming fans be absolutely

aware that there is no similarity (perhaps

even less) between D&D

and AD&D than there is between D&D and its

various imitators produced

by competing publishers.

Just as D&D was the instrument

which made adventure gaming

what it is today, it is

envisioned that AD&D will shape the future of

fantasy adventure gaming.

Where D&D is a very loose, open framework

around which highly imaginative

Dungeon Masters can construct what

amounts to a set of rules

and game of their own choosing, AD&D is a

much tighter and more structured

game system.

The target audience to

which we thought D&D

would appeal was principally the same as that of

historical wargames in general

and military miniatures in particular.

D&D was hurriedly compiled,

assuming that readers would be familiar

with medieval and ancient

history, wargaming, military miniatures, etc.

It was aimed at males. Within

a few months it became apparent to us that

our basic assumptions might

be a bit off target In another year it became

abundantly clear to us that

we were so far off as to be laughable. At least

we had the right subject

material and the right general approach, so two

out of three and all that.

. .

Because D&D allowed such

freedom, because the work itself said

so, because the initial

batch of DMs were so imaginative and creative,

because the rules wre incomplete,

vague and often ambiguous, D&D

has turned into a non-game.

That is, there is so much variation between

the way the game is played

from region to region, state to state, area to

area, and even from group

to group within a metropolitan district, there

is no continuity and little

agreement as to just what the game is and how

best to play it.

Without destroying the imagination

and individual creativity which go into a campaign, AD&D rectifies

the shortcomings of

D&D. There are few grey

areas in AD&D, and there will be no question

in the mind of participants

as to what the game is and is all about. There

is form and structure to

AD&D, and any variation of these integral

portions of the game will

obviously make it something else. The work

addresses itself to a broad

audience of hundreds of thousands of

people—wargamers, game hobbyists,

science fiction and fantasy fans,

those who have never read

fantasy fiction or played strategy games,

young and old, male and

female.

AD&D will eventually

consist of DUNGEON MASTERS GUIDE,

PLAYERS

HANDBOOK, GODS, DEMI-GODS & HEROES,

and

MONSTER

MANUAL and undoubtedly one or two additional volumes

of creatures with which

to fill fantasy worlds. These books, together with

a broad range of modules

and various playing aids, will provide enthusiasts with everything they

need to create and maintain an enjoyable,

exciting, fresh, and ever-challenging

campaign. Readers are encouraged to differentiate their campaigns, calling

them AD&D if they are so.

While D&D campaigns

can be those which feature comic book spells,

43rd level balrogs as player

characters, and include a plethora of trash

from various and sundry

sources, AD&D cannot be so composed.

Either a DM runs an AD&D

campaign, or else it is something else. This is

clearly stated within the

work, and it is a mandate which will be unchanging, even if AD&D undergoes

change at some future date.

While

DMs are free to allow many

unique features to become a part of their

campaign—special magic items,

new monsters, different spells, unusual settings—and while they can have

free rein in devising the features

and facts pertaining to

the various planes which surround the Prime

Material, it is understood

they must adhere to the form of AD&D.

Otherwise what they referee

is a variant adventure game. DMs still

create an entire milieu,

populate it and give it history and meaning.

Players still develop personae

and adventure in realms of the strange

and fantastic, performing

deeds of derring-do, but this all follows a

master plan.

The advantages of such a

game are obvious. Because the integral

features are known and immutable,

there can be no debate as to what is

correct A meaningful dialog

can be carried on between DMs, regardless

of what region they play

in. Players can move from one AD&D campaign to another and know at

the very least the basic precepts of the

game—that magic-users will

not wield swords, that fighters don’t have

instant death to give or

take with critical hits or double damage, that

strange classes of characters

do not rule the campaign, that the various

deities will not be constantly

popping in and out of the game at the beck

and call of player characters,

etc. AD&D will suffer no such abuses, and

DMs who allow them must

realize this up front. The best feature of a

game which offers real form,

however, is that it will more readily lend

itself to actual improvement—not

change, but true improvement Once

eveybody is actually playing

a game which is basically the same from

campaign to campaign, any

flaws or shortcomings of the basic systems

and/or rules will become

apparent With D&D, arguments regarding

some rule are lost due to

the differences in play and the wide variety of

solutions proposed—most

of which reflect the propensities of local

groups reacting to some

variant system which their DM uses in his or her

campaign in the first place.

With AD&D, such abberations will be

excluded, and a broad base

can be used to determine what is actually

needed and desired.

Obtaining the opinions of

the majority of AD&D players will be a

difficult task This is a

certainty. If there are now more than a quarter

million D&D/AD&D

players (and this is likely a conservative estimate)

less than 10% are actively

in touch with the “hard core” of hobby

gaming. Most of these players

are only vaguely aware that Gary Gygax

had anything to do with D&D.

Only a relative handful read THE

DRAGON,

and fewer still have any idea that there are other magazines

which deal with the game.

Frankly speaking, they don’t care, either.

They play D&D or AD&D

as leisure recreation. These are games to fill

spare time, more or less

avidly pursued according to the individual

temperament of the individuals

involved. To this majority, games are a

diversion, not a way of

life. A pastime, not something to be taken

seriously.

D&D initiated a tradition

of fun and enjoyment in hobby gaming. It

was never meant to be taken

seriously. AD&D is done in the same mold.

It is not serious. It simulates

absolutely nothing. It does not pretend to

offer any realism. Games

are for fun, and AD&D is a game. It certainly

provides a vehicle which

can be captivating, and a pastime in which one

can easily become immersed,

but is nonetheless only a game.

The bulk

of participants echo this

attitude. TSR will be hard put to obtain meaningful random survey data

from these individuals simply because they

are involved in playing

the game, not in writing about it or reading about

it outside the playing materials

proper. There are, of course, a number of

ways to surmount the problem,

and you can count that steps will be

taken to do so-the first

is actually in progress now, involving an

increase in readership of

this magazine, for DRAGON has always been

the major vehicle for D&D

and AD&D, and it will remain so in the

foreseeable future.

Conformity to a more rigid

set of rules also provides a better

platform from which to launch

major tournaments as well. Brian Blume

recently established a regular

invitational meet for AD&D “master

players” (in which this

writer placed a rather abysmal 10th out of 18

entries, but what the hell,

it was good while it lasted-). The “Invitational” will certainly grow,

and TSR is now considering how best to establish

an annual or semi-annual

“Open” tournament for AD&D players to

compete for enjoyment, considerable

prize awards, recognition, and a

chance to play in the “Masters”

event. There is no reason not to expect

these events, and any others

of similar nature sponsored by TSR, to

grow and become truly exceptional

opportunities in the years to come.

Good things are certainly

in store for AD&D players everywhere! Not

only will AD&D retain

its pre-eminent position in adventure gaming, but

it will advance it considerably

in the future. More variety, more approaches to play, more forms of the

game, and more fun are in store.

D&D will always be with

us, and that is a good thing. The D&D

system allows the highly

talented, individualistic, and imaginative hobbyist a vehicle for devising

an adventure game form which is tailored to

him or her and his or her

group. One can take great liberties with the

game and not be questioned.

Likewise, the complicated and “realistic”

imitators of the D&D

system will always find a following amongst hobby

gamers, for there will be

those who seek to make adventure gaming a

serious undertaking, a way

of life, to which all of their thought and

energy is directed with

fanatical devotion.

ADVANCED DUNGEONS &

DRAGONS, with its clearer

and easier approach, is bound to gain more

support, for most people

play games, not live them—and if they can live

them while enjoying play,

so much the better. This is, of course, what

AD&D aims to provide.

So far it seems we have done it.

* * * * * *

Judges Guild has been invited

to use this column to comment on

their own unique contributions

to D&D and soon to AD&D also). I hope

that next issue you wil

be able to see what Bob Bledsaw, Chuck Anshell,

and company have to say.

Meantime, all of you who have in the past

made contributions to the

game, or would like to have input in the

future, are reminded that

you have a standing invitation to submit

material for publication

in this column. Articles must be in manuscript

form, of course. Be certain

to send them to me directly, c/o THE

DRAGON.

* * * * * *

For those of you who wondered

why I took certain amateur publishing efforts to task, it was because they

were highly insulting to TSR,

D&D, this magazine,

and myself. That sort of invitation is not likely to go

unanswered by me. It does

not seem reasonable that returning the same

sorts of compliments they

bestowed upon TSR etal, should give rise to

any comment at all—save perhaps

from those on the receiving end.

There are also a couple

of other points which should be mentioned.

Those who read what was

said noted that I mentioned two offerings by

name. This in itself, and

despite the generally bad things said, was

actually a favor, the old

axiom about the superiority of being attacked

rather than being ignored

coming into play. It is true. Coupled with the

comparison to early amateur

press efforts in wargaming, it offers these

publications, and all the

other amateur efforts, a chance to show the

whole hobby just how wrong

and stupid I am by publishing material of

superior quality which does

not resort to invective, character assassination, libel, slander, or various

and sundry cheap shots, relying rather on

honest efforts at quality

contents to interest readers. DUNGEONEER

took this approach in the

first place, and it has done well. Perhaps other

publishers will take a page

from their journal and turn things around in

the amateur adventure gaming

press. If so, I’ll be among the first to give

congratulations, in print!

Meanwhile, I have had the misfortune to view a

so-called professional fantasy

gaming oriented magazine’s first issue;

this contained mostly numerous

boring commentaries by some folks

who are trying hard to make

a name for themselves in gaming, principally by insulting the leaders in

the hobby. This is regrettable but

understandable when one

is dealing with amateurs; it is deplorable in a

professional magazine. Even

though it is the house organ of an aspiring

publisher, such journalism

cannot succeed for long. That sort of work

will have to change quickly

or the magazine won’t see many issues.

So much for this issue’s

SORCERER’S SCROLL. Here’s to the fun

of gaming, win or lose!

"From The Sorcerer's Scroll: D&D, AD&D, and Gaming," by Gary Gygax (The Dragon #26, June 1979):

Because D&D allowed such freedom, because the work itself said so, because the initial batch of DMs were so imaginative and creative, because the rules wre incomplete, vague and often ambiguous, D&D has turned into a non-game. That is, there is so much variation between the way the game is played from region to region, state to state, area to area, and even from group to group within a metropolitan district, there is no continuity and little agreement as to just what the game is and how best to play it. Without destroying the imagination and individual creativity which go into a campaign, AD&D rectifies the shortcomings of D&D. There are few grey areas in AD&D, and there will be no question in the mind of participants as to what the game is and is all about. There is form and structure to AD&D, and any variation of these integral portions of the game will obviously make it something else. The work addresses itself to a broad audience of hundreds of thousands of people—wargamers, game hobbyists, science fiction and fantasy fans, those who have never read fantasy fiction or played strategy games, young and old, male and female.

AD&D will eventually

consist of DUNGEON MASTERS GUIDE, PLAYERS HANDBOOK, GODS, DEMI-GODS &

HEROES, and MONSTER MANUAL and undoubtedly one or two additional volumes

of creatures with which to fill fantasy worlds. These books, together with

a broad range of modules and various playing aids, will provide enthusiasts

with everything they need to create and maintain an enjoyable, exciting,

fresh, and ever-challenging campaign. Readers are encouraged to differentiate

their campaigns, calling them AD&D if they are so. While D&D campaigns

can be those which feature comic book spells, 43rd level balrogs as player

characters, and include a plethora of trash from various and sundry sources,

AD&D cannot be so composed. Either a DM runs an AD&D campaign,

or else it is something else. This is clearly stated within the work, and

it is a mandate which will be unchanging, even if AD&D undergoes change

at some future date. While DMs are free to allow many unique features to

become a part of their campaign—special magic items, new monsters, different

spells, unusual settings—and while they can have free rein in devising

the features and facts pertaining to the various planes which surround

the Prime Material, it is understood they must adhere to the form of AD&D.

Otherwise what they referee is a variant adventure game. DMs still create

an entire milieu, populate it and give it history and meaning. Players

still develop personae and adventure in realms of the strange and fantastic,

performing deeds of derring-do, but this all follows a master plan.

![]()

Quote:

Originally Posted by Gentlegamer

...

This truly shows the insight Gary had into the nature of the game!

Appreciate the post, and

I am sad to say that I did seem to have a good deal of prescience back

then.

Cheers,

Gary

<PRESPOS--> check the title, when you have the Time>