| Dragon | - | Monsters | - | Dragon #81 |

F r o m a n u n t i t l e d t o

m e i n t h e l i b r a r y

o f

S u l p h o n o f W a t e r d e e p ,

s i g n e d ? R h a p h o d e l ,

S a g e o f S a g e s ? : (AD&D?

game notations

and other comments added by the author

appear in italic inside parentheses.)

K n o w , O s a g e , t h a t

a c r e a t u r e o f t e n

a s k e d a b o u t i s t h e

d r e a d e d b a s i l i s k , w h o s e

g a z e t u r n s o n e t o

s t o n e . I t b e h o o v e s a

s a g e

t o w a x w i s e a n d

e l o q u e n t a b o u t t h i s b

e a s t ,

f o r t h e r e i n l i e s t h

e s e e d s o f m u c h

r e s p e c t f o r

y o u r s e l f a n d y o u r l

e a r n i n g .

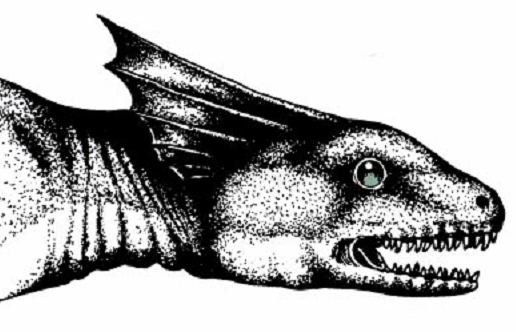

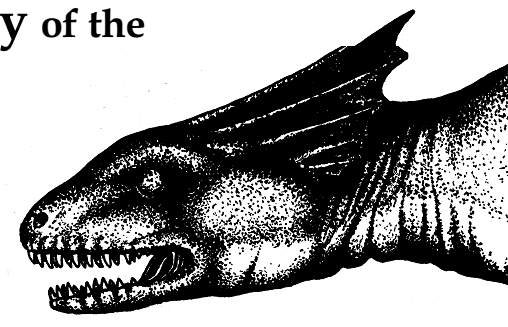

T h e b a s i l i s k i s a

l a r g e , r e p t i l i a n b r u t e

t h a t i s b o t h s l o w

a n d s t u p i d . I t i s

f e a r e d f o r

i t s i n f a m o u s g a z e ,

w h i c h c a n a t w i l l

t u r n

c r e a t u r e s ( i n c l u d i n g b o t

h f i s h a n d f o w l )

w h o

m e e t i t t o s t o n e .

S o m u c h a n y h a l f - w i t

c a n

t e l l y o u , b u t m a r k

w e l l t h e w o r d s t h a t

f o l l o w , f o r h e r e i s

s e t d o w n a l l t h a t

i s k n o w n o f

t h e t r u t h a b o u t t h e

g a z e o f t h e b a s i l i s k

P r e c i s e l y h o w t h e c

r e a t u r e ? s g a z e w o r k s

i s

a m y s t e r y ; m o s t l e a

r n e d o b s e r v e r s a g r e e

t h a t t h e c r e a t u r e ? s

e y e s e m i t a r a d i a t i o n

t h a t

i f a b s o r b e d b y t h e

e y e s o f o t h e r c r e a t u r

e s ?

o r e v e n i t s e l f , i f

i t s g a z e i s r e f l e c t e d

b a c k

u p o n i t ? c a u s e s

a n i n e x p l i c a b l e c h e m i c a l

c h a n g e i n t h e b l o o d

s t r e a m , a l t e r i n g l i v i n g

f l e s h t o s t o n e . (Stoned

creatures are immediately paralyzed, unable to speak, see, or

feel. They will become unconscious from

lack of air at the end of 1 round, but until

then are capable of mental ? i.e., psionic

and some magical ? activity Any spell or

device supplying air, or removing the need

for it, such as a necklace of adaptation, will

allow continued mental activity, with a

cumulative (intelligence score +1% per turn)

chance of insanity due to helplessness and

total isolation.)

C l o t h i n g , a c c o u t r e m e n t s ,

a n d t h e l i k e

c a r r i e d o r w o r n b y

v i c t i m s a r e n o t a f f e c

t e d ,

d e s p i t e s o m e w i l d t

a l e s t o t h e c o n t r a r y .

B e i n g s w h o t h r o u g h

n a t u r a l a b i l i t y o r t h

e

u s e o f m a g i c a r e

i n gaseous form are also

apparently immune to the effects of the

basilisk?s gaze. (The use of invulnerability

potions allows a saving throw vs. petrification at +2. Any rings

or cloaks of protection

being worn add their bonus to the saving

throw.)

A basilisk has two translucent eyelids,

somewhat like the membranes covering the

eyes of a frog, that can at will cover each of

its eyes: an upper eyelid, which drops from

above, and when thus closed overlaps an

inner, lower eyelid, which rises from below

the eye. With the upper and lower eyelids

covering the eyes, a basilisk can see up to 15

man-lengths away (9" in AD&D scale) in

normal light, much as men do. Each eye?s

lids operate independently of each other,

and are controlled by the creature; it need

not blink at all, if no irritants get into its

eyes.

When the upper eyelid (only) is drawn

back, a basilisk?s eye sees up to 18 manlengths away (11"

in scale) on the prime

material plane, with the benefits of both

ultravision and infravision. Or, by concentration, it can scan the

astral plane, seeing

up to 12 man-lengths distant (7" in scale),

or the ethereal plane, seeing up to 18 manlengths away. A basilisk

cannot see on more

than one plane at once, but unless they are

actually fighting or hunting in one particular plane, basilisks tend

to flick their gazes

from plane to plane every minute (every

round), and thus remain aware of their

surroundings in all three planes.

When its inner, lower eyelid is also drawn

back -- and both eyelids can be raised and

lowered again in less than five seconds -- a

basilisk's gaze petrifies all who meet the

stare of one of its eyes on the prime material

plane, slays all who meet its stare on the

astral plane, and turns ethereal creatures

who meet its gaze into inanimate, insensible

?ethereal stone .? Note that a basilisk?s eyes

are on opposite sides of its head, and thus it

commands a very wide field of vision (a

260-degree arc), and can conceivably stone

creatures to either side of it ? two, in total

in the same minute.

Fortunately for those who encounter it,

the basilisk is not particularly energetic or

cunning, and it simply will not comprehend

the properties of a mirror or other reflective

device if such is maneuvered into position,

and will readily ?stone? itself if such precautions are successfully

applied.

Petrified creatures cannot be eaten by

basilisks, and they will therefore strike with

their petrifying gaze only at creatures who

by size or aggressive behavior seem threatening to them. Petrified

victims are subject

to all of the effects that stone normally

suffers. ( These effects include chipping,

frost damage and other weathering, attacks

from a horn of blasting, etc., and these may

well destroy the unfortunate individual.

Contrary to some fireside yarns, stoned

people who are chipped or shattered do not

bleed. Petrification does not otherwise slay

creatures, who are held in a sort of suspended animation, or ?stone

sleep.? Protective devices retained by a petrified victim

?a cube of frost resistance, for example ?

will continue to function. )

Basilisks eat all types of small creatures

(including both fowl and fish), carrion, and

some berries. They cannot eat or physically

attack creatures not on the prime material

plane, and apparently only use their gaze

attacks in a defensive manner with respect

to creatures thereon. It should be noted

here that some sages dispute this point.

Further research, dangerous though it is,

will be necessary to remove all doubt as to

the powers of the basilisk on the astral and

ethereal planes, and possible prey it may

seek from those planes.

Basilisks instinctively avoid looking

directly at other basilisks, and they never

deliberately use their stoning gaze on one

another. They can recognize fellow basilisks

by both sight and smell, and although their

sense of smell is not noticeably keen with

respect to hunting down other creatures, it

is sufficiently acute to distinguish between

individual basilisks; i.e., mate and young

are readily discerned from strangers.

Any basilisks encountered will be solitary

hunters, a mated but hunting pair, a nesting

pair, or a pair with grown but immature

young still sharing a lair. Such young often

accompany their parents for up to three

seasons, until they are ready to mate,

whereupon they leave their parents and

each other to seek out their own mates.

Basilisks mate for life, and by instinct breed

every four summers ? usually in water,

w h i c h h e l p s t o s u p p

o r t t h e i r s l o w , h e a v y

b o d i e s . O n e o r t w o

d a y s a f t e r m a t i n g , t h

e

f e m a l e l a y s a c l u s t

e r o f g r e e n i s h - w h i t e

e g g s

(from 1-8), each about the size of a man?s

fist. Basilisk eggs have soft, warm, stretchy

surfaces, and they withstand crowding or

even gentle handling and tumbling without

harm; they cannot break the way a duck?s

or hen?s eggs will shatter in similar circumstances. A basilisk parent

often picks up an

egg in its mouth to carry it, drops it in a

new location or to defend itself, or rolls eggs

about with its snout ? all without doing the

eggs any damage. After laying its eggs, a

basilisk mother covers them in cool sand or

half-buries them in cool, wet mud. The eggs

are almost always (95% chance) fertile, and

if they survive the nesting period of four to

six weeks (31-50 days), they will hatch into

miniature basilisks, 4 to 9 inches long, who

have full gaze powers at birth. During the

nesting period, the parents do not eat, all

the while growing more and more irritable

and fanatical in the defense of their nest and

its surroundings. Hatchlings grow quite

rapidly, reaching man-size in length (from

nose to base of tail) in 4 to 6 months after

they are born. During this growth period,

their parents hunt intensively with them

and for them.

Like other reptilian creatures, basilisks

are cold-blooded. They derive much of their

energy from the heat of the sun, and spend

much time sunning themselves on rocks or

heights to gather this heat. (They will also

often creep up to campfires at night for the

same reason.) But unlike most reptiles,

basilisks can tolerate a fairly wide range of

temperature, and can also store heat efficiently in their coiled digestive

organs; thus,

they remain active on warm or mild nights,

even in early spring or late autumn. (Basilisks who live deep underground

always

have ready access to volcanic heat ? and if

these subterranean creatures are kept from

this heat source for any longer than a day,

they will grow sluggish and ultimately perish within another three

days.) Like their

smaller kin among the lizard population,

basilisks can regrow lost limbs and tails

within 1 to 4 months, provided they have an

above-average supply of food during this

time.

Because of its fearsome petrifying power

(which, it should be noted, is permanent;

affected creatures are not freed by its

?wearing off?), the basilisk has long been a

source of fascination and magical power to

men. Mages and alchemists have found two

parts of a basilisk eye particularly useful:

the internal pupil, lens, and fluid of its eye

which are used as ingredients in potions,

spell inks, and the making of items (such as

eyes of petrification) concerned with petrifying creatures;

and the inner membrane or

eyelid of the creature, used likewise in

magic concerned with protection against

petrification. Other parts of the basilisk are

sometimes tried for such purposes, but with

little or dubious success. An intact eye

might bring as much as 1,000 gp from an

alchemist; parts of it, such as the eyelid or

fluid, up to 400 gp each. Prices vary with

demand, of course, as with all rarities, and

have been known to reach ten times these

amounts.

Various individuals have attempted to use

basilisks as guardians, usually chained in a

particular location, and fed by hooded

attendants, or led about by them with a

collar and several chains. This tactic can be

effective, but eventually fails more often

than not simply because of the nature of the

beast and its powers. Basilisks are stupid,

lazy, and often asleep. If they feel secure ?

they are not intelligent enough to remain

constantly vigilant if no obvious threat is

afoot ? then they will not look about and

repeatedly scan all three planes, and at such

times they may be slain or hooded from the

rear without great danger to the intruder or

interloper they are supposed to be guarding

against.

And even if a basilisk guard is successful

in its stoning attack, the victim is impossible

to interrogate (or rescue, if the wrong person is petrified by accident),

and difficult to

move out of the way -- except by the use of

expensive spells and magick items. If more

than 1 basilisk guard is used in the same

general area, they inevitably stone each

other

when tricked by cunning intruders, and

starving or beating the beasts does not

improve their drowsy indolence or lack of

alertness. They are simply

too stupid to be

trained where to go or not go, or to distinguish between acceptable

victims and persons who are not to be petrified. Despite all

this, intact basilisk eggs usually bring up to

500 gp each, and a miniature young one is

worth as much as 700 gp. Mature, less

tractable specimens usually carry a price of

450 to 500 gp.

The effective petrifying range of a basilisk's gaze seems to be a function

of how

keen the eyesight of its victim is; although

this tends to be only up to about 5 man-lengths distant (3"

in scale), cases have been

reported of wizards employing wizard

eye

spells being stoned by basilisk guardians,

and persons employing crystal balls, eyes of

the eagle and similar devices being petrified

at great distances.

At present (the time of Rhaphodel?s

writing is unknown), little else is known of

the nature of a basilisk's gaze. The foremost

authority on the subject is widely believed

to be the sage Krammoch. of Baldur's

Gate.