Elephant-sized, 13

hit dice, AC

-3, move 12”, immune

to cold and

charms, animal intelligence

but

with psionic powers,

strikes for 2-

76/2-72 and can spit

acid....

....This sounds like a monstrosity, not

a

monster.

A collection of unrelated numbers

similar to this, rolled on the tables

provided in All the World’s Monsters,

was the cause for merriment at the local

gaming session. Yes, you can “create”

monsters in this random way — you

don’t need tables to do it—but the result

is not a good, imaginative, useful monster,

it’s an unbelievable travesty. There

is an art and a method to creating good

monsters for role-playing campaigns;

one should follow some common-sense

rules — guidelines, really — to avoid silly,

absurd, or illogical creatures.

The 1st guideline, as already indicated,

is avoid random aggregations of statistics.

If you have several dozen charts

and tables — far more than were used in

the case mentioned above — you may

come up with a good monster. But, like

the proverbial monkeys typing randomly,

you’ll wait a very long time for a

Shakespearean-quality creature. If you

think about the whys and wherefores of

the monster, about the background to

the statistics, you can derive suitable

and sensible numbers for speed, armor

class, hit dice, and so on from the monster’s

background, not from dice rolls.

avoid random aggregations of statistics

<italicize the above words>

The 2nd guideline, then, is origins

first. Every monster exists for

a reason, if

only because of survival of the fittest.

Consequently, ask yourself how this

monster came to exist, which usually

means: What ecological function does it

fulfill, as well as or better than any

other

species, which enables it to survive and

reproduce? Sure, you can call something

an “enchanted monster,” created

by the proverbial mad wizard or by a god,

but this is usually a barren excuse, not

a

reason. Unless you desire to give a

monster an ability which is quite unlikely

to have developed naturally, even in a

magical world — say, the ability to teleport

long distances — you should leave

the enchanted monsters and mad wizards

to the dice throwers. Moreover,

when you do devise a monster which is

un-natural, remember that it will probably

be unable to reproduce, and in any

event will probably be very rare indeed.

The 3rd guideline, which ties in very

closely with the second, involves defining

the ecological niche occupied by

a

creature. Your monster species cannot

exist in a vacuum, sufficient unto itself.

It

is part of the world: it affects other

creatures

in its habitat, and is affected by

them, even when adventurers or other

humans are not present.

The monster must fit into the system,

particularly the food chain, without destroying

destroying it. If the existence of the

monster

would alter the balance of nature,

either its characteristics must be adjusted

or you must alter nature in the relevant

campaign areas. The monster must

have a source of food, a means of reproduction

and sustenance which enables

sufficient young to grow to maturity to

continue the species, and places to live.

All of the details of hit dice, armor class,

speed, and other statistics must conform

with the basic needs.

Let’s take an extreme example. Imagine

that many or all rabbits were as

powerful as the rabbit in “Monty

Python

and the Holy Grail,” able

to tear out a

knight’s jugular vein in one swift strike.

This changes only one statistic, the rabbit’s

average damage inflicted per melee

round, but think of the repercussions on

the ecology! Swarms of carnivorous rabbits,

still reproducing at a high rate but

now, let’s say, eating the meat they kill,

would overwhelm the predators which

usually limit the rabbit population. If

you

suppose that these creatures appeared

during the era before civilization, you

can imagine these rabbits covering the

entire world, stopped only by the occasional

great predators such as lions and

tigers. It is necessary, for the sake of

balance in nature, that the fecund rabbits

be harmless eaters of plants.

What about the other extreme? Imagine

a species of dragons that doesn’t

sleep much, produces a cub (or whatever

young dragons are called) every year,

and must eat 500 pounds of meat a day.

Since dragons are the true kings of

beasts, in any area devoid of human or

other highly intelligent (and magical)

interference,

the dragons would soon be

all over, a commonplace — until they ran

out of food. As long as they could expand

into virgin areas, they would spread

like the proverbial plague. The point:

Dragons are so powerful that, unless

there is some limit to their food intake

and reproductive rate, they will sweep

all

before them. A dragon necessarily sleeps

a lot, to reduce energy (food) use, and

rarely begets young. And it’s almost as

necessary that the dragon must live long

before it reaches maturity; that is, before

it can beget more dragons.

The questions

Let’s try to get at this in a more organized

manner. When you consider how a

proposed monster

fits into the ecology,

you can ask several questions:

What does it eat?

What factors, other than availability

of food and habitat, hinder

the growth of numbers of the

species?

Where does it live?

There are many corollary questions,

f o r e x a m p l e :

Is it herbivorous, omnivorous, or

carnivorous?

What routines does it follow to

obtain food?

What natural enemies, diseases,

and difficulties of habitat kill young

before they mature?

What is its reproduction method

and rate?

What is the minimum amount of

territory which will support an individual

or a mated pair?

What terrain and climate is ideal

for the creature, and how much do

deviations from this ideal reduce

the creature’s ability to survive?

What are the creature’s natural

“defenses”?

This may seem a lot to ask, but you’ll

find in practice that everything falls

into

place quickly, or that the struggle to

make it all fit will result in improvements

in your monster design.

The answers

Let’s go back to the two examples to

address these questions briefly. The rabbit

—the real rabbit, not the carnivorous

bunny— is herbivorous, that is, eats only

plants. Let’s assume it eats often but

not

incessantly (I’m not a rabbit expert) —an

“intermittent” eater. It has many natural

enemies which eat young and adult rabbits.

As experiences in Australia demonstrated,

when a foreign rabbit lacking

natural enemies was introduced and

overran the wild, normally predators kept

the numbers down despite the fecundity

of the adult rabbits. If rabbits reproduced

at human rates, on the other hand,

there would soon be very few rabbits.

Rabbits are small, so not much territory

is needed to support a pair, and subspecies

seem to live almost everywhere.

The rabbit’s defenses are speed of flight,

color blending with surroundings, and

small size — a rabbit twice as large as

normal, unless he’d seen Watership

Down, would be no less a

victim of

predators.

The dragon

is another story. One might

say the dragon eats whatever and whenever

it wants, but to conform to the questions

let’s answer that it is a carnivore,

eating only meat. It hunts alone or with

a

mate, and pounces on prey — often from

the air, of course. The dragon has few

natural enemies — man is the most

prominent — but its very low reproductive

rate keeps its numbers down. (Note

that the lower the reproductive rate, the

longer the individual of a species tends

to live.)

Dragons need lots of territory because

they eat so much. Although the long

sleeping periods of a dragon preserve

energy, a creature that big requires a

huge amount of protein and calories to

produce enough energy to fly. Different

species of dragon tend to favor different

terrains and climates; perhaps because

of ‘the dragon’s size, individual species

cannot tolerate deviations from the ideal

As for the last question, a dragon’s best

defense is its great offense: biting, poison,

breath of fire, whatever. But it also

has a very tough skin, the ability to fly,

and (in some cases) intelligence of a low

but formidable sort.

To describe the food-gathering habits

of a species, which have a lot to do with

its statistics, I use categories adopted

from Game Designers’ Workshop’s excellent

game Traveller.

The types are

clearly and thoroughly explained in the

rules; a summary is provided here.

Carnivores eat meat only. Pouncers

are solitary creatures which leap upon

prey from hiding, or after stalking it.

Chasers are usually pack animals which

attack after a chase; they have good endurance

but are not fast. Trappers use

some kind of device or construction to

capture prey. They tend to be solitary.

A

siren

is a trapper which uses a lure of

some kind to entice prey into the trap.

Killers are vicious creatures which attack

almost anything, and which seem to

enjoy killing for the sake of it. Obviously,

pouncers and trappers (and some sirens)

must be able to hide well and move

silently.

Herbivores eat plants or unresisting

animals. Grazers spend most of their

time eating, and for defense rely on flight

or stampede if they are herd animals.

Intermittents are solitary creatures which

spend less time eating. They sometimes

freeze (like a rabbit) rather than flee

immediately

when confronted with possible

danger. Filters take in and expel water

and air, removing nutrients. They

tend to be slow-moving, if not immobile.

Omnivores eat a mixture of plants

and

animals. Gatherers tend to eat plants

more than animals, behaving like intermittents.

Hunters tend toward carnivorous

behavior, while eaters will literally

try to eat anything they encounter. Some

beetles fit into this category.

Scavengers eat the kills of other

creatures.

Intimidators scare animals away

from their kill. Hijackers suddenly steal

dead prey and carry it off. Carrion-eaters

eat meat not wanted by the original

killers and stronger scavengers. Reducers,

such as bacteria, continuously consume

dead organic matter.

Some information garnered elsewhere:

Carnivores tend to be territorial (see

below) and more

intelligent than herbivores.

The majority of carnivores hunt at

night, and consequently tend to be color

blind. They also depend as much on

hearing and sense of smell as on sight.

Omnivores tend to hunt alone. Carnivores

hunt alone, in pairs, or in packs.

Not surprisingly, carnivores require a

much larger area per creature than omnivores

or herbivores, because they’re at

the top of the “food chain.” For example,

a square mile might support one (9-18

pound) carnivore, 20 omnivores, and up

to 100,000 herbivores.

If a creature

seeks food alone (or with

its mate), rather than in a pack or herd,

it

may exhibit territorial behavior. During

mating time, at least, an individual will

occupy an area large enough to supply it

(and its family) with food, and chase

away any other creature of its species

which attempts to cross the boundaries

of the area. Its mate is the exception,

of

course. In many species the males set up

territories and then try to attract females.

Territories can be very sharply defined.

For example, a bird may violently

attack a mirror placed within its territory,

seeing its reflection as a rival, but if

the

mirror is moved just inches beyond the

boundary the bird will ignore it. An interesting

kind of monster would hotly pursue

any intruder in its territory — but

stop dead at the border unless the intruder

attacked it.

Other creatures have fixed abodes but

are not territorial outside the lair, while

yet others wander about for most of the

year. If the monster is an egg-layer, it

might stop for more than a few minutes

to lay its eggs before moving on. Creatures

which rear their young —mammals

and birds, for example — will have different

territorial habits from those which

ignore their young.

Defenses

Defenses can be classified as those

which merely protect or preserve, and

those which harm an enemy. The first

category includes speed of movement

(to facilitate escape), agility (for dodging),

unusual means of movement (flight,

burrowing), avoidance mechanisms such

as camouflage and small size, sheer bulk

(how many predators can kill an elephant

or a whale?), tough skin (including

dangerous coverings such as that of

the porcupine), magic, and intelligence.

The second category includes some of

the above, such as speed and agility,

size, strength, “viciousness” (which can

make up for a lot), intelligence,

and magic.

And in either category, numbers

count, or perhaps we should call it cooperation

among individuals — for example,

in herd animals which warn each

other of danger, or in pack animals

which hunt together.

The food chain

When you think about ecological

niches in your world which might be

filled, consider first those which ought

to

be filled, lest the system fall apart.

For

example, several writers have pointed

out that with all these monsters around,

from orcs

up to dragons, the food chain

in the wilderness must be sorely strained.

That is, while plants convert sunlight

into food, something must convert plants

into animal matter for the numerous

predators (and omnivores) which we

find in a fantasy world. Perhaps there’s

a

peaceful, fairly large herd animal, with

several subspecies, which reproduces at

a high rate and efficiently converts plants

to its own animal matter. The predators

then live off these herds. Cattle and bison

are rather large and dangerous prey

for many predators, but some creature

like those, though smaller, might do.

In dungeons, too, one finds a foodchain

problem in an artificial ecology.

The inhabitants can’t live off one another

(or there would be no one left for adventurers

to fight), and in many dungeons

it’s impossible for all the inhabitants

to

obtain food from outside, if only because

the region would soon be barren. I’ve

solved this problem in my world by creating

a giant “mushroom” which uses absorbed

heat from the earth, in place of

sunlight, to provide the energy which is

converted into food.

Even undead and enchanted monsters

must fit into some ecological niche, insofar

as they cannot crowd out natural

species. Fortunately, these un-natural

monsters reproduce very slowly, if at all;

on the other hand, they do not die naturally.

They don’t normally disturb the

food chain because they don’t eat, but

they may disturb or destroy the habitats

of natural creatures, and some may kill

natural creatures just for the hell of

it. If

the local inhabitants can’t fight back

—

imagine orcs against a powerful demon

— then the enchanted monster or undead

is going to strongly affect the ecology.

This must be considered on a caseby-

case basis, depending on the purposes

and vulnerabilities of the un-natural

monster.

Getting ideas

So much for guidelines two and three,

origins first and ecological niche. Actually,

I find that sometimes the origin

comes second, not first. While the origin

must be a part of the creature consistent

with everything else, the impetus for

creating the creature may be a desire to

devise a monster with one unusual ability

— say, a telkinetic power which enables

it to partially immobilize a victim.

Once you know what power you wish to

use, you can think about how this power

might originate, and how the monster

might fit into the ecology.

Moreover, I find that building a monster

around some unusual power results

in a usable, perhaps outstanding, addition

to the “world.” Unless it is afar out or

extremely powerful ability, the monster

is unlikely to be too powerful to use,

and

you automatically avoid the danger of

piling several abilities atop one another

to create a super monstrosity.

The guidelines pertain primarily to

monsters you make from whole cloth,

from your imagination, but most also

apply to modifications of real beasts,

and to your own versions of mythologi

cal, legendary, and fictional creatures.

Probably the average DM is better off

basing monsters on fiction or on real

creatures, at least to get some experience

before he begins to make them up

without a ready-made background.

Real beasts are a great source of ideas,

if you’re willing to do a little research.

Most people know a little about the habits

of mammals, but next to nothing

about insects, birds, fish, and plants.

Merely by increasing the size of a beast,

you can create a monster out of an innocuous

creature. (Yes, such increases

in size, including giant humans, are contrary

to the laws of physics. But these

laws must stand aside somewhere; assume

that an unidentified magic nullifies

the square-cube relationship.)

Take birds, for example. The thrush

likes to throw nuts against stones in

order to get at the edible part. Might

a

giant thrush, or some monster with similar

proclivities, try to smash a knight

against a rock in order to get the “nut”

out? The shrike, a small bird with surprisingly

predatory tendencies, sometimes

impales its victims on its beak. Think

of a

(domesticated?) giant shrike streaking

into a party to impale a magic-user! What

could a Pegasus rider do if harried by

a

flock of giant bluejays (which, in the

real

world, can drive away owls and hawks)?

Or, take bugs. Spiders conceal themselves

in a variety of ways when waiting

for prey —such as the tent spider, which

builds an opaque web tent to hide under

until prey comes near. Other types actively

catch flying creatures with web

nets, while yet others wait in holes in

the

ground. One even emits a sticky substance

to immobilize a victim’s feet. Giant

army ants would be formidable, for reasons

we can all imagine.

Several species of carnivorous

plants

can be easily adapted to fantasy games,

such as the Venus flytrap. Plants in the

sea, or animals resembling plants, also

catch and eat other creatures.

You can also vary the habitats or abilities

of real beasts. Someone has made

up land sharks, and what about flying

lions or burrowing wolves? Many legendary

beasts, after all, are merely misperceptions

of real animals or combinations

of them (e.g., the chimaera). But try not

to forget the guidelines to monster making.

I have my doubts about land sharks...

For legendary monsters, you usually

have some means of comparison with

“real” beasts. If you know, for example,

that a legendary monster was supposed

to be twice as dangerous as a lion, and

a

lion has been defined in your game, you

can work from there to determine statistics

for the new creature. If a roc can

carry an elephant, it must be much larger

than said elephant. If a man on a winged

horse could travel twice as fast as a real

horse, you have some basis for assigning

numbers to the creature.

Monsters from

fiction

In general, legendary creatures tend

to be one-shot, made by someone, not

fitting into the ecology, so you need this

kind of comparison to give you some

idea of what the monster can do. But

monsters drawn from fiction — for example,

orcs from

Tolkien

or Kzinti from

Larry Niven —often come complete with

background information about how they

fit into the world. You may have to modify

the creature — for example, by reducing

the Kzin to animal intelligence — in

order to make it fit into your ecology.

There’s a tendency to make creatures

derived from myth and fiction overpowerful

because the DM forgets to take the

fictional ecology into account. Classic

among these is the tendency to rate Tolkien’s

Gandalf — he’s a kind of monster,

isn’t he? — as an umpteenth-level wizard

merely because he is virtually the only,

and therefore the most powerful, spellcaster

in Middle Earth. But if you compare

what he can actually do with what

characters from your game can do, you’ll

find that he wasn’t very powerful at all

—in terms of the D&D®

or AD&D™ rules,

maybe an eighth-level cleric with a magic

ring and the ability to use a sword.

Similarly, just because some monster

dominates a work of fiction, the DM

thinks it should dominate or be powerful

enough to dominate his world. He forgets

that many role-playing worlds have a far

higher proportion of powerful magic and

powerful creatures than any world of

fantasy or science-fiction in literature.

(Note that the words an author uses to

describe a creature don’t necessarily

have the meanings used in your game.

Gandalf is a “wizard” because he uses

magic, but this doesn’t mean he must be

a wizard, that is, magic-user, in a game

such as the D&D game, which

allows for

several types of spell casters.)

You can vary legendary or fictional

monsters, too — for example, a cockatrice

which paralyzes or causes insanity,

a foot-long Pegasus, a unicorn which

shoots missiles from its horn, a ghoul

which flies. Make them larger or smaller,

change speeds, change means or medium

of locomotion, and so on.

Not “all or nothing”

Whatever type of monsters you create,

try to avoid dogmatic or draconian pronouncements.

The “rule” is: Avoid all-or

nothing characteristics. For example, a

monster

which is vulnerable only to certain

rarely used spells, or only to a series

of three or four spells cast in a particular

sequence, is a poorly designed creature.

If the players have ample opportunity to

learn of these peculiarities before they

encounter the beast, it will be a usable,

but not outstanding, creature. Aside from

the all-or-nothing nature of the creature,

which is bad for the gaming aspect of

role playing, it’s hard to explain how

this

unusual characteristic evolved. Even if

the creature is enchanted, why in the

gods’ names was it created with this odd

Achilles heel? Another example of this

mistake is the monster which is deadly

unless you know the trick which makes it

harmless. The Pictish

demons, for example

(as described in the Gods, Demigods

& Heroes supplement to the original

D&D rules) are frightening until

you

learn to lie down —then they ignore you.

This is an amusing change of pace for a

one-shot creature but would not work

for a standard inhabitant of the world.

An example of how to create a monster

with one special power and avoid all the

pitfalls might help. Let’s begin by giving

the new creature a simple telekinetic

power. The creature can hold down or

immobilize an enemy or victim, or knock

fruits off a tree, but it could not use

telekinesis

to pull a lever, turn a knob, use a

knife, or do any other detail work, even

if

it were trained to do so.

Unless the creature is very large, it

could not immobilize a large victim —the

victim would drag the monster along.

For no particular reason except a prejudice

against giantism, let’s take the alternative

approach: that the creature

hunts in packs to cooperate in immobilizing

large prey. Yes, the creature does

hunt — otherwise why the need for this

telekinetic power? And flesh-eating monsters

are more fun, so let’s say this creature

is an omnivorous hunter which eats

animals primarily, but is not averse to

an

occasional juicy fruit or plant stem.

Hunting in packs reminds me of the

wolf. Wolves rely on their endurance to

run down a victim, but let’s not follow

the

wolf idea too closely. Perhaps our creature

pounces on prey, utilizing its telekinetic

power. If the prey isn’t caught within

a few seconds, the monster won’t try

to chase it. Having no need for speed,

our monster is relatively slow, but must

hide well in order to surprise its victims.

It must live in areas providing cover —

probably brush or forests with heavy undergrowth,

certainly not plains. Since

the creature lies in wait for prey, it

hunts

when most animals are active—the daytime,

especially when new or failing light

increases the chance of concealment.

Wolves are built for a long run, but our

monster need not be. And unlike the

wolf, it doesn’t need to fight — its prey

is

immobilized and helpless. So, let’s say

the creature is four-legged but rather

fat

and roly-poly roundish, weighing 50-60

pounds. It is not equipped with sharp

teeth. Instead, it has a mouth shaped like

an elephant’s trunk, through which it

sucks a victim’s blood (or a plant’s juices)

until the victim is nearly dead. Then

the monster can chew bits of dead flesh

slowly, perhaps over several days. Because

the monster is slow and often sits

immobile for hours, it uses little energy

and eats surprisingly little for its size.

To settle questions of reproduction,

let’s recall our sort-of model, the wolf.

We’ll say our monster has one litter of

6-8

live pups per year, in spring (mammalian).

Many die from their inability to keep

up with the pack. Those that survive mature

in 6 months and live for about 5

years, if they’re lucky. The pack is promiscuous;

males and females do not

have “mates” per se, but can freely intermingle

provided the pack leader does

not object.

Generally, lone animals of this species

could take small prey, but would fare

poorly in areas frequented by large animals,

especially large predators. Perhaps

an individual driven from one pack would

join another — nature’s way of insuring

against continual inbreeding. Sometimes

an overlarge pack might divide, or two

packs reduced in numbers by fights,

famine, or disease might merge together.

The packs may be loosely territorial.

Probably an area of many square miles

could support only one typical pack of

10-40 individuals, which would continuously

move about within the territory.

Altogether, this monster’s role is that

of a medium-sized flesh eater which can

take both small prey, like rabbits, and

the

occasional large animal, like cattle, without

presenting much danger that it will

overrun the countryside.

This creature’s natural defense is numbers

and cooperation between members

of the pack. The latter may require a significant

intelligence. Armor class, hit

dice, and attack statistics need not be

outstanding, for the creature relies on

telekinesis and its considerable size.

A summary of the

creature’s statistics

as they might be expressed for use in an

AD&D™ adventure are as follows:

FREQUENCY: Rare

NO. APPEARING: 10-40

ARMOR CLASS: 8

MOVE: 3”

HIT DICE: 2

% IN LAIR: Nil

TREASURE TYPE: Nil

NO. OF ATTACKS: 1

DAMAGE/ATTACK: 1-2 plus suck blood

for 1-4 per round thereafter

SPECIAL ATTACKS: Telekinesis

SPECIAL DEFENSES: Nil

MAGIC RESISTANCE: Standard

INTELLIGENCE: Semi to low

ALIGNMENT: Neutral

SIZE: S

PSIONIC ABILITY: Nil

Attack/Defense Modes: Nil

When the creature hits a victim it attaches

to it and sucks blood each round

thereafter until one or the other is dead,

or until the pack flees. The creature can

stand immobile for hours. Its hair tends

to be the color of the terrain it typically

hides in — e.g., dark greenish in a forest.

The creature surprises on a 1-4 on a d6

in

suitable terrain when lying in wait.

Thanks to their intelligence, these animals

are easily trained, but they occasionally

choose to ignore orders.

The telekinesis ability is easy to define

now that we‘ve determined the other

characteristics. Each creature can immobilize

animals up to 30 pounds (300

gp) in weight at close range (up to 1”),

20

pounds at medium range (1”-2”), and up

to 10 pounds at long range (2”-3”). It

cannot move while using telekinesis unless

it is holding less than half the allowable

weight. Several can join together to

hold one victim, perhaps taking turns so

that all can approach and “drink.” The

weights given assume the victim is not

unusually strong for its weight. And if

the

victim is only partially immobilized, it

moves at a proportionately slower speed

— effects may be compared to those of a

slow spell. Humans and many other

creatures also gain a saving throw vs.

paralysis which, if successful, effectively

halves the weight the monster’s telekinetic

power may hold.

What about a name? I keep a list of

names I’ve picked up from literature,

from other players, and who knows

where else, because I’m not much good

at making them up. I call this monster

the

“Starkhorn” — for its “trunk,” I guess

—

but perhaps you can think of something

better.

-

Aside from simple encounters in the

wilderness, this monster may be most

useful to a DM when domesticated to

guard an area or to assist a magic-user.

I don’t want to give the impression designing

monsters is a mechanical process.

Inspiration, if not romanticism, is a

necessary element, particularly when the

monster first takes shape. Without a decent

idea, you won’t get good results.

The sources and guidelines described in

this article will help you turn a good

idea

into a good monster, and help you avoid

turning a lousy idea into a lousy monster.

But no one can tell you how to turn a

lousy idea into a good monster.

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

ARCANE

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

ARGOS

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

Broken One (Lesser &

Greater)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

Deepspawn

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

ELEMENTAL, COMPOSITE

(Tempest, Skriaxit)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

EYEWING

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FEYR (Feyr, Great Feyr)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

GIANT, WOOD (VOADKYN)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

HATORI (Lesser, Greater)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

INSECT

SWARM

(Grasshoppers and Locusts)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

GIANT-KIN, CYCLOPS

(cf. CYCLOPS, LESSER)

(cf. CYCLOPS, GREATER)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

PORCUPINE (Black, Brown, Giant)

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

-

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

UNKNOWN

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

PEGATAUR

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

WHITE APE

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY:

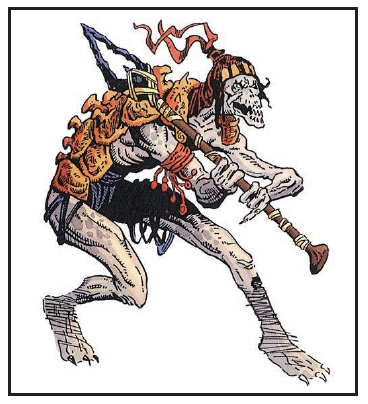

PICTISH BAG OF

DEMONS

A magical device that summons 10-100 creatures

from its interior. It is 16" by 30" and sealed with beeswax. The demons

are half-man half-bird with 35 HP. They are as strong as a Fire Giant and

they will not attack anything lying flat on the ground.

FREQUENCY:

NO. APPEARING:

ARMOR CLASS:

MOVE:

HIT DICE:

% IN LAIR:

TREASURE TYPE:

NO. OF ATTACKS:

DAMAGE/ATTACK:

SPECIAL ATTACKS:

SPECIAL DEFENSES:

MAGIC RESISTANCE:

INTELLIGENCE:

ALIGNMENT:

SIZE:

PSIONIC ABILITY: