| Dragon magazine | Pernicon (revised) | - | Monster Manual III | Dragon #108 |

| - | - | Notes | - | - |

(The following are excerpts from the

diaries of the Emir of Yandark, later High

Sultan of Kiralsh, Jesouhd Ye?esif.)

During my recent visit to the eminent

Colonel Endrivan of Olcoran, once an

adventuring companion of mine and always

a friend, he expressed some interest in a

creature he had heard lived in the Iriahb

Desert of my homeland. This creature, the

insect known as the pernicon,

captured his

interest for the water-divining powers which

have made it known. We discussed the topic

for some time, since I have had some expe-

rience with the creature in my desert tra-

vels. It seems to me that little is commonly

known about the pernicon, and many

?facts? about it have been distorted. Since

visiting with the colonel, I have taken some

interest in the particulars of the creature

and learned what new things I could of it. I

record here that which I have learned, and

hope the knowledge will be of use to the

desert traveler and naturalist, and of inter-

est to others.

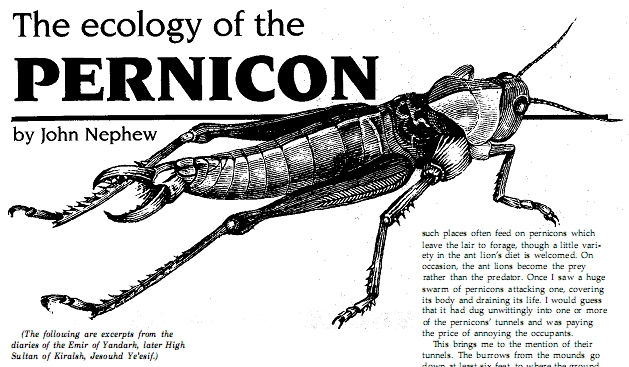

The pernicon is in basic form similar to a

locust, or grasshopper, of about two inches

in length. There are several points that

distinguish it from its smaller cousins. Col-

oration is vastly different, with red, yellow,

ochre, and blue being common, as well as

some rarer shades among those, such as

orange-yellow or greenish-yellow. Another

difference I have seen is that the pernicon

lacks wings ? it is a crawler and jumper.

(1)

The pernicon lives in the outer reaches of

deserts, probably so that it has a supply of

vegetable matter available for consumption

when there is a lack of animal life(2); again,

unlike the grasshoppers and locusts, it is

truly an omnivore. The creature feeds on

animals by jumping on them and clenching

exposed flesh (or soft body parts, in the case

of some creatures) with pincers at the rear

of its abdomen. Through this, the insect

drains the fluids of the victim ? and often

its life. (3)

The pincers continue to siphon out one?s

endurance even if the insect is slain, and

removal of the pincers is a delicate and

painful task. (4)

Though they are small and weak, the

trouble in killing pernicons lies in hitting

them, because of their size and swift hop-

ping. Always beware those pincers; a perni-

con dodging your blow may at the same

time be launching its own attack. Of course,

a pernicon that is attached to you makes a

much easier target. (5)

One seeking these creatures should hope

to find a small foraging group of pernicons,

rather than the thousands that infest a lair.

Though one or two cause little trouble to

anyone with fighting experience, a large

group poses a threat even to the most able

of warriors. (6)

The lairs of the creature are found near

the desert?s edge (7), as mentioned before,

near their plant and animal food supplies. A

lair almost resembles a town, being made of

many mounds resembling large anthills

raised from the sand.

I caution the reader to remember that

they are hills, with burrow entrances. Make

sure that they are just that; near many

pernicon ?towns? are the pits of ant lions,

which are giant insects of greater power and

aggressiveness. Those ant lions living in

such places often feed on pernicons which

leave the lair to forage, though a little vari-

ety in the ant lion?s diet is welcomed. On

occasion, the ant lions become the prey

rather than the predator. Once I saw a huge

swarm of pernicons attacking one, covering

its body and draining its life. I would guess

that it had dug unwittingly into one or more

of the pernicons? tunnels and was paying

the price of annoying the occupants.

This brings me to the mention of their

tunnels. The burrows from the mounds go

down at least six feet, to where the ground

is more firm. It is here that the pernicons

rest, breed, and spend much of their time.

They dig long tunnels, each usually no

more than half an inch high ? which is

ample space for the insects. I have heard

from some men and women of the desert

that the pernicons, by their water-detecting

powers, tend to dig down where there is a

supply of ground water. I would suppose

then that in some places there would be

tunnels going down a hundred feet or more!

The learned sage Elkir Hildar of Ye?nassa

told me that they need these humid ?wells?

to lay their eggs in, lest the eggs shrivel up

and the young die before birth. (8)

After the pernicons have eaten all the

food near their ?town,? they move on to

another location, abandoning their old lair

to seek a new place with more food. The

entire colony moves at once ? a great

multicolored blanket moving across the

land: crawling, jumping, devouring every-

thing in their path until they find a suitable

site for a new tunnel complex. (9) Hundreds

die on the journey, but hundreds more live.

They are the hated enemies of farmers and

those who live off the fertile land. As they

eat plants around their new ?town? in great

quantities, they enlarge the desert.

But just as the farmers loathe them, the

nomads and travelers of the desert treasure

them almost beyond gold. The antennae of

the creature have a curious water-detecting

power. When within two score yards of

great amounts of water (10), the antennae

vibrate and hum.

The creature?s water-divining power has

been cause for much speculation and theo-

rizing among sages. It does not seem to be

magical in a strict sense; many bards con-

sider a sunset magical, and augurs see

magic power in the flight of birds and the

entrails of beasts. This is, however, no place

to argue the difference between ?magical?

and ?natural.? No magical power is re-

quired in the preservation process. Through

the length of the antenna from outer tip to

anchor is a clear, oily liquid. In the presence

of the elements of earth and air it remains

still, but water causes the fluid to become

agitated, vibrating the antenna. Close con-

tact with fire renders the liquid a brittle

solid, which has no divinatory powers. The

sage Carthin of Ethrenor speaks of each

element having its own radiation (similar to

the energy of the Positive and Negative

material planes), and suggests that the

antenna?s content is sensitive to the radia-

tions of the water element. (11)

Among many nomadic tribes, the perni-

con antenna is a sacred religious object

offered by some shamans to their deities for

water. (12) To some desert cultures, the insect

itself is sacred and is the symbol of deities.

The ancestors of one nomadic tribe I know

of sacrificed criminals to the pernicon

swarms. It is ironic that while some hold the

pernicon sacred for religious reasons,

among other groups (most notably the

royalty and very wealthy classes of my land)

the pernicon is sacred for culinary reasons.

There are several ways to prepare the in-

sect, though always the antennae and pin-

cers are removed. In my favorite recipe, the

pernicons are fried in olive oil and served

with salt and camel butter. Cooked prop-

erly, they are light, crispy and delicious;

furthermore, they are a status symbol indi-

cating great wealth. Attempts have been

made to domesticate the creatures, but none

yet successfully.

Despite being a culinary delicacy, even

more valued are the creatures? antennae, as

mentioned before. It is not easy to find

them on the market. Near the eastern edge

of the Iriahb Desert, in the city of Grindar,

they are sold for considerable sums of

money, but they are often improperly pre-

served (disintegrating in the buyer?s hands

moments after being purchased) or were not

correctly removed from the creature (and

thus are completely useless). In all likeli-

hood, you will have to find and preserve the

antennae yourself to ensure their quality.

The first problem, once you have found

and slain the pernicon, is the careful re-

moval of the antenna. The antennae have a

bulbous portion not far below the outside of

the skull. This anchors the antenna, but still

allows it movement. There are tiny muscles

in the anchoring chamber. With them, the

antennae may be moved together or in

different ways. This is helpful in finding the

direction of water. One antenna is aimed

one direction, and the other the opposite.

The creature can detect the most minute

difference in the frequency of vibration, and

the antenna vibrating faster is closer to the

water. Humans using an antenna have to

move around, with the antenna indicating

the direction of the source.

Beneath the ?anchors,? the very bases of

the antennae are short, thin projections with

rounded tips. Each tip touches a sensitive,

rubbery tissue atop the creature?s brain.

This tissue detects the vibrations of the

antennae (if any) and the direction it is

aimed, and sends them to the brain, which

can interpret the signals.

To correctly remove the antenna, the

skull must be pulled apart to either side of

the anchor, and the antenna cut free from

the muscle tissue and removed. Most pro-

fessionals use a special tool, a spring-

tweezers, to remove the antenna; if these

are not available, the next best things are

some of the more delicate instruments

found in most sets of thieves? too1s. (13)

Though small and delicate, an antenna

lasts quite a while if you care for it well. If

allowed to become damp, it disintegrates. It

is by nature dry, and immersion in water

causes it to explode harmlessly.

An antenna is also brittle, and crumbles

to dust unless handled with utmost care. It

is good to have it stored carefully and used

only when necessary. The Bilndiah nomads

have a simple but effective means of storing

their antennae, which I use myself and

recommend to all travelers. They use a

bone map case, in which is placed a roll of

camel hide (with plenty of cushioning fur)

around the antenna. It does an excellent job

of protection, so that the antenna will usu-

ally remain intact even if dropped quite a

distance; (14) it also keeps the antenna silent

and still when not needed. If the case is

watertight, it is even more useful. Some

folk, such as some merchants I know, prefer

metal or wooden cases, often inlaid and

decorated with precious metals and stones.

A last word of advice must go to the

traveler: The antenna can only detect water

? if there is no water near, the antenna is

of no more use than another grain of sand.

Notes

1 -- The distance that a pernicon can

jump varies greatly. This author suggests a

base horizontal range of 10? and a vertical

range of 5?. These figures should be ad-

justed at the DM?s discretion, in consider-

ation of such factors as wind speed and

direction, and temperature. Pernicons

function more sluggishly in lower tempera-

tures, but this is not generally a factor in

their desert environment.

2 ? Despite his travels and knowledge of

the desert, the Emir has made a small mis-

take. The pernicon?s diet does not consist

mainly of other animals, as he appears to

imply. They are primarily herbivores. Je-

souhd Ye?esif is, though, accurate about the

creatures? method of attacking. Creatures

?eaten? aid the creature by providing

much-needed liquids, and some nutrients,

but pernicons cannot live on fluids alone.

3 ? Note that the pernicon?s attack form

will not harm certain creatures greatly, if at

all, at the DM?s discretion. The ?immune?

group should include all undead, most

elementals and para-elementals (including

such creatures as the thoqqua, dune stalk-

ers, grues, etc.), some outer-planar crea-

tures, golems, and so on. The DM should

remember how the pernicon harms ? it

sucks out body liquids. If a creature has no

body fluids, it won?t be harmed, except by

the pincer being clamped on or pulled off.

4 ? This author considers 1-4 hp dam-

age for the removal of a pincer of ½ inch in

length (at most) to be excessive, and recom-

mends only 1 hp damage be taken instead.

5 ? A pernicon attached to a victim has

AC 10. Note that if an attack is made on

such a pernicon and the attack misses, a ?to

hit? roll against the victim should be re-

quired 50% of the time, with no dexterity

adjustments applicable. Even if the pernicon

is killed, its pincers remain in the vic-

tim, as noted in the FIEND FOLIO® Tome,

p. 72.

6 ? For dealing with combat between

pernicons and armored characters, refer to

the accompanying article.

7 ? An inhabited ?town? of pernicons

will rarely, if ever, be located more than a

mile from the border of the desert.

8 ? Female pernicons lay eggs twice a

year. Special moisture-holding chambers are

made by the pernicons, by gluing grains of

sand together with sticky saliva (produced

from fluids drained from victims), to hold

the hundred or so eggs deposited by each

female after mating. Because of the thin,

membranous shells of the eggs, they have to

be deposited on moist sand lest they shrivel

up and die before hatching. This is the

reason that the pernicons tunnel down to

reach ground water or moisture (which is

closer to the surface near the border of the

desert), and the major reason that they

possess water-detecting antennae. After

sand on the chambers? floor is sufficiently

dampened and the eggs deposited, the

chamber is sealed by saliva-glued sand to

contain the moisture. The young hatch

within a week or so and eat their own shells

(and sometimes their neighbors? shells, or

even their neighbors). They then burrow

out to join the colony. As the average, only

1-6 of a pernicon?s hundred laid eggs will

survive to maturity.

9 ? There is a 1% chance that an en-

counter with wandering pernicons will be

with a moving colony, in which case the

number appearing will be the lair size

rather than the normal ?wandering? size

(i.e., 300-3000 rather than 4-40). Player

characters meeting such a group are advised

to get as far away as possible, as fast as

possible. Pernicons en route to a new lair

are particularly aggressive, since they will

need animal fluids for the construction of

the tunnels and egg chambers of the new

lair (see note 6).

10 ? The FIEND FOLIO Tome is vague

as to what a "large quantity" of water is.

This author recommends that any water

body of 5,000 gallons or more should be

easily detectable. Smaller amounts should

be detectable at closer ranges.

<Pernicon, FIEND FOLIO>

11 ? This could be compared to the

liquid-crystal display in digital watches.

Electricity causes the liquid crystal mole-

cules to align in such a way as to absorb

light, becoming visible to the observer. The

radiations of water cause the pernicon an-

tenna?s oily fluid to behave in the opposite

manner ? going from a neutral state to

chaotic and agitated. Fire causes the re-

verse, the liquid going to a rigidly struc-

tured form. Submersion in water destroys

the antenna; the oily substance disperses

rapidly, bursting out of and shattering the

antenna.

12 ? If a pernicon antenna is used by a

cleric or druid as an additional material

component for a create water spell, the spell

will produce 10%-60% more water than it

would otherwise. As with other material

components, the pernicon antenna will

disappear after the spell is cast.

13 ? Successful removal is not auto-

matic. The base chance, rolled on a d20, is

equal to the dexterity of the character (or

the average of two characters) attempting

the removal, modified as follows:

If the first time ever tried, -10 (then -9

on the second, -8 on the third, etc.);

If special tools are used, + 2;

If thieves? tools are used by two charac-

ters, no adjustment;

If thieves? tools are used by one character,

-2; and,

If other tools are used, such as hairpins,

-2 (two characters) or -4 (one character).

The task requires the total concentration

of the individual(s) involved. If work is

disturbed before finishing the removal,

there is an 80% chance of the antenna

being ruined.

14 ? Pernicon antennae should have

saving throws for resisting damage from

falling. Normally 20 is the proper save, but

in such a bone case, it should be 10, ad-

justed upward by 2 for every 10? fallen. A

metal case grants a base saving throw of 8.