-

Part I -- Introduction and Overview

-

-

Part I -- Introduction and Overview

-

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dungeons & Dragons | - | Dragon magazine | - | The Dragon #22 |

To students of military history, the age known as the Renaissance

can be said to extend from the end of the Hundred Years War in 1453,

to the final ban on pikes issued by Queen Anne of England in 1703.

The

period began with the dominance of the armored lancer, and ended

with the dominance of the musket armed foot soldier. In this series,

we

will examine the major armies/types of soldiery found in Renaissance

Europe, and the tactical systems that went along with them. The period

is an immensely fertile one for the wargamer, full of color and variety

with troops ranging from Swiss Pikemen to Hungarian Hussars, Feudal

Knights to pistol wielding Reitiers.

Generalship in this era rose to a degree of expertise not seen since

classical times, Gonzolo de Cordoba, Gaston of Foix, Maurice of

Nassau, and Gustavus Adolphus, all left an indelible mark on the art

of

war. It was the age of the great Vauban, who revolutionized the science

of siegecraft and fortification by the end of the 17th century. We

will

begin our study by examining the state of the art as found in the first

half

of the 15th century.

Warfare consisted for the most part, of disorganized melees with

occasional glimpses of genius found here and there in England and

France, and the phenomena of the Hussite Wars. The infantry, before

its resurgence, played little part in a battle until the opposing cavalry

forces had finished. The armored feudal knight was the dominant force

on the battlefield, and the poorly armed and trained infantry (for

the

most part) could do little to stand up to a charge. Certain developments

however, signaled the revival of the foot soldier. There were three

major

developments which will be discussed briefly here, and in more detail

later on when concerned with particular armies.

The Hundred Years War between England and France had already

begun the resurgence of the infantryman, due primarily to the use of

a

single weapon, the English Longbow. First used in the campaigns

against Scotland and Wales, the longbow was the most efficient missile

weapon of the pre-gunpowder era (i.e. before the introduction of efficient

arquebuses and muskets), though some would argue many years

later, that it was still more efficient than a musket. In fact such

a notable

person as Benjamin Franklin urged its adoption as the standard arm

of

the American forces in the revolution. Nevertheless, its rapid rate

of fire,

more than three times that of a crossbow, gave to the footsoldier for

the

first time, a weapon that would allow him to hold his own against

cavalry. Interestingly, it was also found to be very effective when

used in

conjunction with cavalry, against the other major infantry weapon,

the

pike.

The pike first made its appearance as a major infantry weapon in

the Low Countries, Flanders and the Brabant, and soon spread to

Scotland and Switzerland. It was an ideal weapon for use by ill-trained

troops on the defensive, but in the hands of well-trained infantry,

it

could be a deadly offensive tool. Varying in length from 12 to 21 feet,

the pike allowed infantry to keep cavalry at bay, while missile armed

troops shot them from the saddle. The heyday of the Swiss Pikemen was

yet to come, but already by the mid-fifteenth century, they had built

a

fearsome reputation for bravery and skill.

The third great weapon that arose to sound the death knell of

Feudalism, was the Hussite wagon laager developed by Jan Ziska of

Bohemia. Ziska had seen a version of the laager used in Poland against

Teutonic Knights and Russians, and it seemed the ideal weapon for an

army made up predominantly of lightly armed and badly trained

peasants. He took the idea one step further however, training his men

with strict discipline and religious fervor, Ziska turned the wagon

laager

into a remarkable offensive tool.

The combination of these three forces, caused military leaders to

reassess and re-think the value and use of the armored horseman. The

introduction of early gunpowder weapons made the horseman’s position

even more untenable and before long, new types of mounted

troops began to appear.

The Hungarians and Venetians in their constant warfare with the

Ottoman Empire, had long realized the value of light, fast moving

cavalry for skirmishing, scouting and raiding. The Venetian cavalry,

called Stardiot, could be called the forerunners of dragoons, for armed

with spear, bow or crossbow, they were equally adept at fighting

mounted or on foot. The Hungarian cavalry were the famous Hussars,

and constituted their national fighting force. Without a real army,

the

Hungarians had to rely on levies who could be raised on short notice,

and counted on effectively to deal with any threat. Armed with a bow

and curved saber, the Hussars were fierce, light and fast moving, and

by

the end of the next century their imitators could be found in many

armies.

The Renaissance was the great age of the Mercenary, and until

France and Sweden began to raise national armies, mercenaries were

in

great demand throughout Europe. Swiss, Flemings, Landsknecht,

English and many others, offered their services to the highest bidder,

each using the weapon with which they were most proficient. One might

find English longbowmen loosing their shafts in the service of Italian

Dukes, or Genoese crossbowmen backing up the charge of French

knights. While their reputation has never been good, most mercenaries

could be counted on to render excellent service to their employers,

as

long as the purse remained open.

Artillery was in its infancy at the beginning of the period, but steadily

improved in quality throughout the age, with the French and Spanish

making the greatest advances. By the beginning of the War of the Spanish

Succession (1701-1714) massive batteries of cannon were common,

and sieges began to replace open field battles as the most common

type of military activity.

In short, this is a period about which enough can never be said, and

in the articles that will follow, we will examine in depth the major

participants

and weapons of the age.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Machiavelli, Niccolo

The Prince

The Art of War

The Discourses

Oman, C.W.C.

The Art of War in the 15th Century

The Art of War in the 16th Century

Mattingly, Garrett

The Armada

Dupuy & Dupuy

The Encyclopedia of Military History

Wise, Terence

Medieval Warfare

Monluc, Blaise

The Journal of Blaise du Monluc

Next time, we will begin our study with the most famous of all the

soldiery to come out of the age, The Swiss Pikeman.

-

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dungeons & Dragons | - | Dragon magazine | - | The Dragon #24 |

The sturdy, mountaineers of Switzerland have always had a fierce

desire to be free and independent. Being primarily a pastoral people,

and never a great power, they had scant resources to raise a powerful,

well-armed fighting force. However, their tremendous bravery and loyalty

made them fierce foes, and with a few simple weapons they forged

a formidable fighting force. Three weapons were responsible for the

Swiss rise to greatness; The Halberd, The Pike and The

Crossbow. Before

the pike came into vogue it was the halberd that served as the main

arm of the mountain peoples. Charles The Bold and Maximillian of

Austria were both victims of the halberd’s deadly blade. Defending

the

mountain passes leading into their country, they presented an impenetrable

wall of steel, halberdiers, backed up by armored men with

great two-handed swords and Lucerne Hammers. Made with a broad

axe blade as its main weapon, a long point for thrusting, and some

fashion of hook to pull riders from their horses, the halberd was indeed

a

murderous weapon, and in the hands of a brawny Swiss mountaineer, it

could cleave through the finest armor in Europe, and flesh and bone

as

well.

The well known legend of William Tell, illustrates the skill of the

Swiss with another deadly weapon, the crossbow. The effectiveness of

the crossbow in puncturing heavy armor, made it an ideal weapon for

the lightly armored Swiss infantry, who had to defend themselves

against armored Imperial cavalry and infantry. The crossbowmen generally

functioned as skirmishers ahead of the main army and then faded

back once the battle was joined. When effective handguns were introduced,

the Swiss were quick to pick up on them, and used them to

replace at least a portion of their crossbows. By 1500, 80% - 100%

of

their light troops were armed with handguns and arquebus.

It was the pike however that made the Swiss infantryman the terror

of Europe, and the most sought after mercenary of the age. The average

pike of the Renaissance varied in length from 16 to 18 feet. The Swiss

used a monster 21 feet long with 3 feet of steel protecting the tip

from

being slashed by swords or axes. The tremendous weight of the weapon

was such that it required great strength and training to use it properly.

In

the hands of the Swiss, it achieved an effectiveness not seen since

the

days of Alexander the Great.

The Swiss did in fact adopt the ancient phalanx formation used by

Alexander, but improved on its use substantially. First, instead of

using a

single phalanx flanked by supporting troops, the Swiss used three

phalanxes, a Van, a Main Battle and a Rear, each assigned a specific

task on the battlefield. They were generally echeloned back from the

right, with the rear battle refused until needed. The van would begin

the

attack by striking the flank of the enemy, as the main battle pushed

into

the center, the rear battle waited to see where it was most needed.

and

generally provided the final push that would result in victory.

The second improvement was in the cohesiveness and stability of

the individual phalanx. The phalanx of ancient Greece was found to

be

completely disorganized when drawn on to rough ground, where the

hoplites could not keep proper step. The Swiss however, were so well

trained that they could advance over any sort of terrain without losing

step. They were the only infantry of that age, or perhaps of any age,

capable of taking the offensive against cavalry. They were remarkably

fast at the charge, and the sight of this veritable forest coming at

full

speed, was enough to shake even the bravest enemy. Only with the

introduction of the Spanish Sword and Buckler men and later the

Landsknecht, were soldiers found who could meet the Swiss on an

almost equal footing. It is interesting to note however, that in contests

between the Swiss and their Landsknecht copies, the Swiss were almost

always victorious.

The individual soldier was generally poor and unarmored, his sole

protection might consist of a leather jerkin and an open helmet. The

gaudy uniforms usually associated with the Swiss, were really not

worn until the early 16th century, and even then did not approach the

color of the Landsknecht. The nobles, and others who could afford

some degree of armor, were generally formed as the front ranks of the

phalanx, or armed as halberdiers and two-handed swordsmen who

would stay in the rear until melee was joined. The crossbow and handgun

armed skirmishers, generally made up any where from 10% to

30% of the entire army, and would have been completely unarmored.

There is some indication that armored crossbowmen were used for defensive

purposes, usually wearing half-armor and a visored sallet.

Cavalry was used in small numbers, and was generally made up of the

wealthier gentry or German allies, and was equipped and used as the

typical heavy, armored knight of the period.

The downfall of the Swiss came in their total disregard for the use

and effectiveness of artillery. At battles such as La Biocca and Ravenna,

their tightly packed phalanxes took a terrible toll from the efficient

Spanish artillery, and once their formations had been broken, they

were

easy prey for the disciplined Spanish infantry. Even after these disasters,

the Swiss maintained their reputation, and were sought after mercenaries

throughout the period. They made up the major part of the

French infantry all through this era, and even after the day of the

pike

had ended, regiments of Swiss infantry remained in the French army

through the Napoleonic Wars, and formed the basis for the renowned

Foreign Legion of the 19th century. Their loyalty to their employer

was

well known, even when less desirable elements entered their formations,

they remained one of the best trained and disciplined infantry

formations in Europe.

Colors for their uniforms are generally left up to the imagination of

the individual wargamer, though the Swiss Guards of the Vatican generally

wore orange and blue stripes. Many flags were carried, for a single

phalanx could contain men from many cantons, each with their own

distinctive color. The Swiss were one of the primary forces in the

resurgence

of the infantry man, and made up an era of the Renaissance

that should not be ignored.

Next Time — The Condotierre and the Papacy.

(For more information on the Swiss Armies, See The

Irresistible Force

by Gary Gygax in TD-22).

Part III -- The Condotierre and The Papacy

-

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dungeons & Dragons | - | Dragon magazine | - | The Dragon #25 |

If Woody Allen would ever decide to turn his comedic talents to

writing history, the result would very probably read like a history

of Italy

in the Age of the Condotierre. Few periods in history could possibly

be

as full of petty squabbles and pointless maneuvering, as this age when

greedy, mercenary captains controlled the destiny of the Italian City-

States. Warfare was formalized to the point where it almost became

a

life-size chess match, with few fatalities. However, their military

system

does assume a certain importance in our study of the period.

With few exceptions, which will be discussed, the majority of the

city-state forces, consisted of high priced, un-enthusiastic condotierre

mercenaries. The Condotierre captains, realizing how expensive a

commodity they had to offer, strove constantly to find a way to reduce

casualties in battle, and increase the number of wealthy, ransomable,

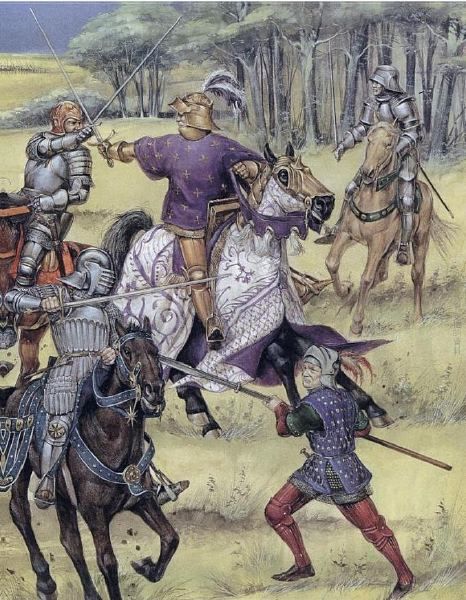

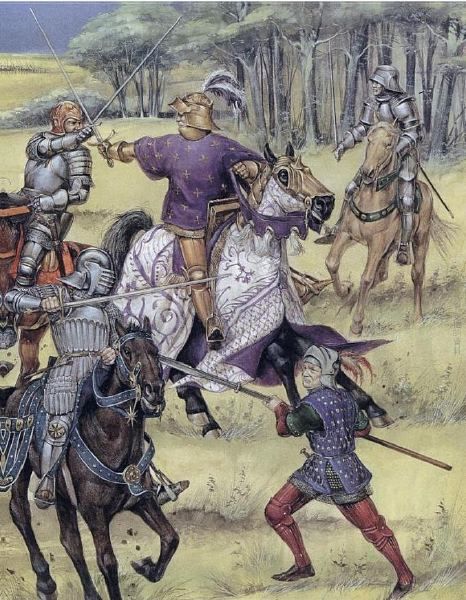

prisoners. Naturally the first way to reduce casualties, is to arm

men so

heavily that it becomes almost impossible to kill them. This resulted

in

armies moving slower and slower, a full charge being almost impossible.

The lack of movement eventually resulted in battles becoming a series

of intricate maneuvers, where the primary objective would be to force

your opponent into an untenable position, where he would either have

to surrender, or be cut down by crossbowmen, whose heavy bolts could

penetrate the heaviest armor.

Later, when the need for mobility was realized, the Condotierre

captains began to employ a type of light cavalryman known as a

Stradiot. The Stradiot served essentially as a dragoon, trained to

fight

on horse or foot, and very useful for scouting and skirmishing. The

infantry of the Condotierre companies consisted almost entirely of

lightly armored missile troops. Crossbows tended to be the most common

weapon, with longbows used occasionally, and later on, small

numbers of handguns found their way into the formation. One quite

notable exception to the norm, was the famous White Company of Sir

John Haukwood. This force of English mercenaries, consisted of its

height of 2,000 longbowmen, many veterans of the French Wars, and

2,000 mounted men at arms. They were well known for their bravery

and outstanding service to their employers.

The native forces of the individual city-states, consisted almost entirely

of infantry, and varied in quality from miserable to decent.

Machiavelli’s famous experiments with the Pisan militia, showed that

locally raised levies could be made into a competent fighting force,

when adequately trained and led. Generally, the levies were armed with

a variety of polearms, glaives, bills and halberds being common. The

amount of armor depended on the wealth of the city, and the particular

way in which the troops were used. Garrison troops tended to be more

heavily armored than field troops. The forces of the more powerful

cities, Genoa, Venice, Milan and Florence, tended to be a bit more

competent than most. The Genoese crossbowmen had of course built

up a fair reputation for skill in France, and were considered prize

troops.

Generalship on the whole, was not outstanding, the Sforzas, the Borgias,

and the Medici were about the best that could be found, though

they could hardly be called great captains. Machiavelli was the preeminent

tactician and strategist of the day, but he was more concerned

with matters of state, not commanding armies in the field. His “Art

of

War,” is a classic work, but unfortunately was not read widely enough

by his contemporaries.

The use of artillery was virtually non-existent, until the lessons of

the French invasion in 1490, taught them the value of cannon. Even

the

Venetians still used Greek-Fire on their galleys, and only mounted

small

pieces of cannon for close fighting. Interestingly though, it was an

Italian,

Niccolo Tartaglia, who invented the gunner’s quadrant in the later

16th century, that enabled artillerists to set range and trajectory

more

accurately. Inventiveness was certainly not lacking in the minds of

Italian

thinkers, for DaVinci’s notebooks are full of ingenious and highly

advanced military weapons, and most Italian artists dabbled to a degree,

in military affairs.

There is a tremendous paradox in Italian affairs in this era, in that

the most powerful and most militaristic of all the rulers was the Pope,

the

representative of God on earth, the most “peace” loving of all men.

In

reality though, the Papal States presented a tight confederation of

vassals,

who swore undying loyalty to the Pope. The two Popes who figured

most greatly in this era, Gregory and Alexander, were masters of

political intrigue and manipulation of petty nobles. The core of the

Papal forces was the Pope’s personal guard of Swiss mercenaries. Their

loyalty was legendary, and they provided unshakable support to the

less reliable levies of the Pope’s vassals.

As for costume, this is a very fertile era for the imagination. The

mercenary companies generally wore some sort of uniform dress or at

least colors, according to the whim of the captain. Hawkwood’s White

Company, as its name implies, wore white surcoats emblazoned with a

red cross of St. George. The city-states generally fielded levies dressed

in their ordinary clothing, embellished with armor, and usually gave

them some type of sign to wear taken from the city coat of arms.

The Italian forces then, should not be ignored in games set in the

earlier Renaissance, and when painted with imagination, they can provide

a tremendously colorful spectacle on the wargame table.

Next Time: The English from St. Albans to The Boyne.

| - | - | Bibliography | - | - |

| Dungeons & Dragons | - | Dragon magazine | - | The Dragon #25 |

England’s insular position has, throughout history, made it slower to

adopt new trends than its brothers on the continent. Nowhere was this

more apparent than in the military sphere. Up to the reign of Queen

Anne, (1701 - 1714). the English army remained a curious mix of

medieval and modern ideas, fortunately molded into an efficient fighting

force. Here, we will attempt to examine the major trends in English

military development, and how it effected and was affected by developments

on the continent.

The first and foremost factor in England’s rise to power was the

adoption of the Welsh Longbow during the reign of Edward I in the 13th

century. Its effectiveness in the Scottish Wars, when properly coordinated

with cavalry, was devastating. Many a Scottish warrior, and later

French Knights, died with a cloth-yard shaft in his breast, a mute

testimony to the skill of the English yeoman.

Through succeeding reigns up to the early 17th century, the longbow

remained an important part of England’s armory. Muster rolls,

from Queen Elizabeth’s reign, show a fair proportion of longbows, along

with musket, pike and bill, and the royal guard always contained large

numbers of archers. It was not until improvements in infantry firearms

and armor made them vastly superior, that the English finally accepted

the fact that the day of the longbow was past. It is interesting to

note, that

during the “Wars of the Roses”, when both sides used essentially the

same weapons and tactics, that battles were not decided by longbow

vollies, but in fierce and bloody melees with maul and polearm. The

memory of the longbow’s power was so strong in the military mind that

Benjamin Franklin would seriously suggest its adoption as the national

weapon of the American forces during the Revolutionary War.

English ability with other weapons was not to be passed over lightly

however, for the combination of bill, pike and musket turned back many

a determined charge. In fact, the English gained such a reputation

for

discipline and courage during the 16th century that they were as eagerly

sought after by their allies, as they were avoided by their enemies.

English troops seemed to wear less armor than other European armies;

infantry often wore nothing more than a brigandine of jacked leather

with a motion or cabaset for their head. Pikemen, following continental

practice, usually wore back and breastplate, and tassets protecting

their

thighs.

By the time of the Civil Wars, the English forces presented a “proper”

continental appearance, officered by men who received their

training in the Low Countries and France. By this time regiments were

normally made up of one-third pikemen and two-thirds musketeers,

other hybrid weapons had by now faded away. It was during the Civil

Wars that the familiar red coats came into widespread use, and in fact

became a national uniform with the creation of the New Model Army in

1644-45.

If any arm was truly neglected by the English, it was their cavalry.

Historically, the English have been a nation of foot soldiers, and

in their

Civil Wars, cavalry played a small, though often significant role.

On the

continent however, the English found the need for numbers of quality

cavalry. By Queen Elizabeth’s reign, English and Scottish lancers,

though few in number, were highly regarded by their allies, and more

often than not, decided the tide of a battle by a charge at a decisive

moment. Armor, for the cavalry of Elizabeth’s reign, ranged from chainmail

or jacked leather for the light horse, to three-quarter cuirassier

armor on the lancers.

From 1645 to 1698 the English military went through a phase of

constant change and improvement. Uniforms altered in design and cut,

armor reduced to the barest minimum and the red coat almost universally

accepted as the trademark of the British soldier. The English

troops, who fought in the Low Countries under William I from 1689 to

1697, were tough professionals, and under leaders like Monmouth and

Marlbourough, they saved many a close situation. Their courage is

dramatically shown in the fact that casualty lists almost always contained

a higher proportion of British dead than any other.

In 1698 however, disaster struck. The War of the Palatinate (The

War of the League of Augsburg), ended in 1697 with the announcement

of the Edicat of Nantes. The English people, embroiled in warfare

of one sort or another since 1640, were sick of fighting and the constant

drain on their purses. They demanded that William and Parliament

reduce the army to its barest possible level, approximately 9,000 men,

to defend the island. William pleaded with the people to reconsider

their

request, pointing to the political situation on the continent, Spain

in

particular, as just cause to keep the army up to strength. Fortunately,

the

answer to the crisis came from the continent. In 1700 Charles XII,

King

of Spain, died. The claimants to the throne included a relation of

Louis

XIV, thus the new King could rule France, Spain and the Holy Roman

Empire at one time, wielding immense military and political power.

Louis XIV followed this event, by formally revoking the Edict of Nantes,

and German and Dutch troops mobilized for war.

In the midst of this sudden outbreak of war fever, with England

preparing to respond to calls from the continent, William died, leaving

the country in the hands of his capable successor, Queen Anne. She

vigorously pursued the war policy and urged the country to stand

behind her and her general, the Duke of Marlborough. The English

troops that Marlborough took overseas were well drilled parts of a

finely

tuned machine, the likes of which had never before been seen on the

European continent. Marlborough’s “Red Caterpillar”, as the immense

column of troops was known, ushered in the beginning of a new era in

warfare, that left behind the pike and arquebus, and brought to the

fore

bayonet and Brown Bess.

Next time: Part V The Armies of Eastern Europe

Bibliography

Churchill, W. — The Life and Time of the Duke of Marlborough

in 4 volumes

Cruikshank — Elizabeth’s Army

Rowe, H.L. — The Expansion of Elizabethan England

Mattingly. G. — The Armada

Oman, C.W.C. — The Art of War in the 15th Century

Oman, C.W.C. — The Art of War in the 16th Century

Cole, H. — The Wars of the Roses

Rogers, H.C.B. — Battles and Generals of the Civil Wars

*Nascati, N.F. — Cromwell and the Rise of the New Model Army

*Nascati, N.F. — The Rise and Development of the British Army from 1689 to 1714.

*These are both unpublished manuscripts, N.F.N.

Part V -- Armies of Eastern Europe

-

| - | - | Bibliography | - | - |

| Dungeons & Dragons | - | Dragon magazine | - | The Dragon #25 |

Warfare in Eastern Europe (for our purposes, Poland, Hungary,

Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, etc.) evolved along very different

lines

than the formalized linear warfare of Western Europe. This land,

covered as it was with rolling plains, steppes and grasslands, has

been,

since ancient times, a land of horsemen. From the hordes of Attila

the

Hun to the mailed Spahis of Suliman, wave after wave of horsemen

have swept out of the East. The major countries of Eastern Europe each

refined the mounted warrior to suit their own special tastes and

thoughts; these individual systems will be the subject of this article.

The one unifying force that decided the final design of military

systems was that of defense against the hordes of Turks and Tartars

that

swept out of the Middle East. A study of these forces will be a fit

starting

point. The Tartars are the simpler of the two forces, essentially being

the

descendents of the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan. Basically light

horse-archers and spearmen, the force was bolstered by a small number,

approximately 30%, of medium/heavy lancers. Their tactics as well

were similar to the five rank formation of the Mongols. Under their

greatest leader, Timur the Lame (Tamerlane), they cut a wide swath

of

destruction through the Ukraine and other parts of southern Russia

and

Asia. After his death however, their discipline and victories faded

quickly.

The army of the Ottoman Empire however, is a very different story.

It is interesting to note that they were the disciplined core of infantry

for

support. This core was the famous (or infamous?) Corps of Janissaries.

These troops were raised as children from Christian slaves, to become

one of the most efficient fighting forces of Renaissance Europe. Originally,

they were armed with a strong composite bow and a saber. It was

not long however, before firearms were generally adopted; not long

after that they became highly proficient in their use. The Janissaries

were not however, trained for maneuver. Their primary function was

to

form a stable base around which the Ottoman cavalry could maneuver

and reform.

The Ottoman cavalry was the cream of their army, at least most of it

was. The regular cavalry was fairly evenly divided between the elite,

heavy Spahis of the guard, and the light Timariot, who were horsearcher/

lancers. The Spahis, in full mail and helmet, were the equal of all

but the heaviest European cavalry and formed the core of the Ottoman

offense. The Timariot wore a light shirt of mail and a light helmet

and

used a strong composite bow to launch arrows a great distance. They

also carried a scimitar and light lance for melees.

From 30% to 50% of the horse consisted of irregular light cavalry,

who acted as skirmishers and scouts and were variously armed with

scimitars, bows, javelins etc. Their overall value was minimal, though

they did have their proper place in the tactical scheme. The last component

of the army, which could be included here, is the Azabs. These

were large groups of light irregular infantry, used as skirmishers

who

were armed with bows, muskets, etc.

The Ottomans had a healthy regard for artillery and were always

well supplied with ordinance, usually more so than their Eastern European

opponents. They had little trust in their hired gun crews however,

who were very often chained to their guns.

The principal opponent of the Ottoman advance was the disunited

Kingdom of Hungary. Along with Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania

(which often fought on the side of the Ottomans), a heroic resistance

was maintained up to the middle of the 18th century. The Hungarians

are unusual, in that they were the only European nation to have a

national force of horse archers of sufficient quality to oppose the

Turks.

These were, of course, the famous Hussars. Trained to act as one with

their horse, the Hussars were brave and daring, and when properly

supported, they could undertake some remarkable assignments. Armed

with a composite bow and saber, and later two pistols, the Hussars

wore

no armor save for an occasional mail shirt, and they relied on their

speed and accuracy to accomplish their tasks. Supporting the Hussars,

the Hungarians fielded heavy, feudal cavalry, similar in most respects

to

the armored lancers of Western Europe, except for certain national

costume details. Other cavalry units consisted of light Wallachian

and

Moldavian lancers, some Tartars, and Croatian light cavalry, which

were similar to the national Hussars.

Being a nation of horsemen since the days of their Maygar ancestors,

the Hungarians had to look to mercenaries for a source of reliable

infantry. From Germany, they hired pikemen and crossbowmen. From

the Hussites of Bohemia, they hired companies of handgunners and

additional infantry. These troops seemed somehow more trustworthy

than the mercenary companies of Western Europe. Perhaps the seriousness

of the Turkish threat gave them a common bond that went beyond

monetary considerations.

The Kingdom of Poland held a position of great importance

throughout the period, though they were often more concerned with

the raids of Russians and Teutonic Knights than the Turkish threat.

Cavalry was also the core of the Polish army, though not the light

horse

archer of the Hungarians. The Polish Hussar (as you can see, the

confusion on the origin of the term has deep roots) was a heavy

cavalryman modeled along the lines of the Byzantine Cataphract His

equipment consisted of a heavy breast plate, shoulder and wrist protectors,

tassets, and heavy, leather boots. Their armament was extensive,

consisting of a mace, two swords (one curved, one straight), two pistols,

a lance and often a bow. The famous Winged Hussars were an elite unit

drawn from veterans of the line formations, and were often held in

reserve to deliver the final, decisive blow. It was not uncommon to

find

the Winged Hussars under the personal command of the Polish King, as

with John Sobieski at Vienna in 1685.

Other types of Polish cavalry included Cossacks recruited from

Lithuania, who fought with saber, javelin and bow, Polish light lancers,

and the Pancerni, a curious looking medium cavalryman. The Pancerni

wore a thigh length mail shirt, a mail hauberk topped by an odd looking

flat cap, and heavy boots. They were armed with saber, bow, mace, war

hammer and shield, and later added a brace of pistols to their equipment.

During the 17th century the Poles began to form companies of dragoons,

who wore a long coat like the infantry, and carried musket, saber,

pistols

and an axe.

Polish infantry played a secondary but not unimportant role in

battle. Like the Janissaries, they formed a solid base around which

the

cavalry could maneuver. However, they were also trained and armed

for the attack. They wore no body armor, except for the protection

provided by their heavy clothes. They were normally armed with a long,

curved sword and a musket. In addition, many carried a two-handed

axe, which was used both in melee and as a rest for the heavy muskets

of

the period. Pikemen, though few in number, were included in the

infantry units, and were useful in both attack and defense.

The last of the great powers we will discuss is Russia. Beginning with

Ivan IV (The Terrible), Russia began to spread its might throughout

the

East, fighting several wars with Poland and the Tartar Khanates. The

army of Ivan The Terrible was a curious mix of medieval and modern

forms. The cavalry was small in size compared to the other Eastern

powers, and was fairly evenly divided between light horse archers,

and

heavy, mailed lancers. The horse archers wore a padded jacket for

protection over bright, peasant tunics, and low boots into which were

tucked colorful, baggy trousers. Their weapons consisted of a composite

bow, saber and mace; they were generally used for harassment, skirmishing

and scouting.

The heavy cavalry wore a variety of armor protection, from ring mail

to scale armor to metal plates sewn on to ring mail. They fought with

a

heavy lance, sword and mace, and carried a large shield. Most wore

a

simple conical helmet, often with a chainmail neckguard, nobles added

a screen of mail which protected the eyes and nose. The cavalry forces

were also augmented by hiring large numbers of Cossacks from the

steppes.

Russian infantry varied greatly in type and quality, and was often

supported by units of German mercenaries with pike and musket. The

best Russian infantry were the Streltsi of the Imperial Guard. They

were

all armed with musket, saber and axe, and wore a long, orange or

yellowish-brown coat. The elite Streltsi of the Czar’s bodyguard, wore

a

very unusual uniform, consisting of tight chain mail trousers tucked

into

boots, a mail shirt with brass strips for added strength, and a mail

hauberk with a face screen similar to that of the noble cavalry. These

bodyguards were generally armed with a bardische (a long, Russian

battle-axe), and a saber.

Other Russian infantry included Zaporozian peasants who fought

with battle-axe and saber, and foot Cossacks, generally armed with

musket, arquebus or crossbow, who acted as skirmishers and scouts.

With the exception of the Turks, none of these countries had any real

appreciation of the power and importance of artillery, and were very

slow to adopt to Western methods. In fact, ambassadors sent to Russia

by Elizabeth I of England, commented on the military maneuvers of

large numbers of horse archers.

It was not until the reign of Peter the Great, that the Russians saw

the

need to adopt Western methods. He took the polyglot, antiquated army

and turned it into a first class fighting machine. He introduced artillery,

and made sure that his gunners were well trained. By the time of the

Great Northern War in 1700, the Russian army could hold its own

against the best. Peter’s crushing defeat of Charles XII’s Swedish

army

was firm proof of the fact.

Overall, the inclusion of a few Eastern units, or entire Eastern

European campaigns, would make a colorful and interesting sidelight

to

your normal Renaissance wargames.

Next Time: Landsknechnts and Reiters

Address All Questions and Comments To:

Nick Nascati

2320 So. Bancroft St.

Phila., Pa. 19145

Bibliography

Churchill, W. — The Life and Time of the Duke of Marlborough

in 4 volumes

Oman, C.W.C., The Art of War in The Middle Ages.

Oman, C.W.C., The Art of War in The 16th Century.

Dupuy and Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Military History.

Chandler, D., The Art of War in the Age of Marlbourough.

Gush, G., Renaissance Armies.

Part VI

Landsknecht and Reiters

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dungeons & Dragons | - | Dragon magazine | - | The Dragon #37 |

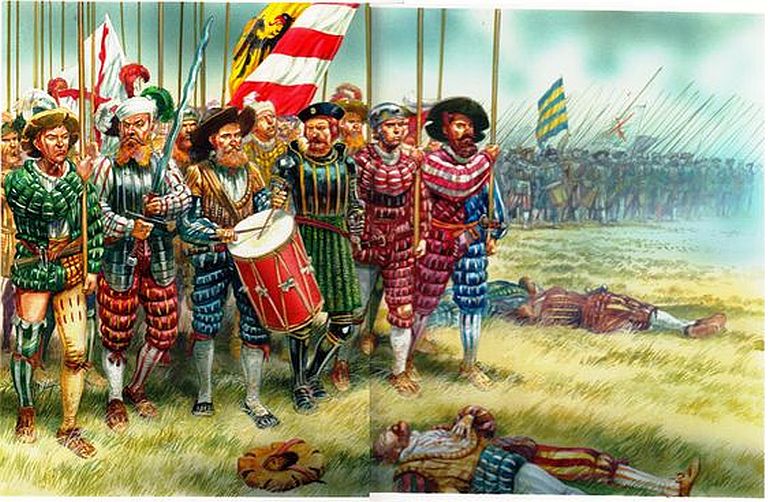

By 1475, the reputation of the Swiss Pikemen

had been firmly

established among the armies of Western Europe. There were few, if

any, bodies of organized troops who could withstand their awesome

charge. After 1500, the Swiss served almost exclusively with the

French, so it was obvious that some type of counter-measure was

needed. About 1490, the first steps were taken.

Maximillian of Austria, the Holy Roman Emperor, saw how crucial

the need was to develop a competent force of infantry to oppose the

Swiss. He appointed Joachim Von Frundsburg, a competent general

and veteran of many campaigns, to accomplish the task. Von Frundsburg

took on his job with relish, and was determined to match the

Swiss. He began by hiring veteran infantry from all over the Empire

and

Europe; sturdy Brabanters and Flemings, Germans of every description,

Italians, Spanish, even French, flocked to the rich and wide-open

purse Von Frundsburg offered.

Heavy cavalry came in two varieties, ritters and reiters. There is

some confusion about the two similar terms, but the following explanation

should be clear.

The ritters were typical armored lancers, similar to those found

throughout Western Europe. They were fully clothed in plate armor

and carried a heavy battle lance and a long, straight sword. Their

horses

often had plate armor as well, to protect them from crossbow bolts

and

bullets. These troops were the primary shock force of the Imperial

army, and one can well imagine the sort of impact such heavy armored

men would have on an opposing line.

The reiters were the infamous, black-armored pistoliers of the

Imperial army. Their dress went through two phases. They originally

wore full plate armor to the waist, with heavy boots on their legs

and an

open helmet on their head. Later, as the need for more mobility arose,

two distinct types emerged. One was a very lightly armored reiter

whose only protection may have been a light chainmail shirt, and who

wore a soft, pilgrim-type hat and heavy boots. The other wore a

long-sleeved mail shirt under a black breastplate, with an open, lobstertype

helmet. The one constant factor in both phases was armament.

The reiters carried three wheelock or matchlock pistols, two in saddle

holsters and one generally stuck in a boot. For close-in fighting they

carried a long, heavy sword known as an estoc. Their horses were often

all black as well, and were unarmored so as to give them maximum

speed for maneuvering.

The tactic most often associated with the ritters was the picturesque

and complicated caracole. This formation consisted of a column at least

six deep of reiters, performing a tightly drilled move-and-fire piece

which was devastating to opposing infantry. Each line in turn trotted

up

into pistol range; each man discharged two of his pistols and then

wheeled around to the back of the formation to reload. This tactic

was

especially useful against opposing pike formations. The concentrated

fire would knock holes in the dense formation, and the reiters would

charge in to exploit the gap.

Von Frundsburg had done his work well. He reviewed with justifiable

pride the fine troops he had trained. They were better than

anything else the Empire could field. The question was, however, could

they beat the Swiss? In the initial contests the Landsknecht were

devastated; the Swiss fought with tremendous ferocity against these

Germans who copied their tactics.

As they gained more experience, however, the Landsknecht defeats

came less and less frequently. The Swiss at the same time were slipping

more and more in discipline, and found that they were often hard

pressed to hold back the confident Landsknecht.

To the Landsknecht, war was either good or bad. A good war was

one in which they were able to take many prisoners for ransom and

fatten their purses. A bad war was one in which they faced the Swiss,

for

they knew that quarter would be neither given nor expected.

The major difference between the Landsknecht and the Swiss

remained one of ethics rather than tactics. The Landsknecht, for all

their training and discipline, were mercenaries. Their loyalty would

depend on the generosity of their employer, and on the way the war

was going. It was not unlikely that a whole company would defect or

at

least refuse to fight, if they felt it was not in their best interests

to do so.

The Swiss, even when they fought for the French, served with fierce

loyalty.

The costume of the Landsknecht was generally more garish than

that of the Swiss. The mercenaries favored colorful, full blouses covered

with sashes and ribbons, and huge, floppy hats gorgeously decorated

with ostrich plumes. Later, toward the end of the 16th and into the

17th century, the costumes were toned down. Descriptions of Landsknecht

from the 1620’s usually find them wearing leather jerkins over

their clothes.

All in all, the Landsknecht certainly represents one of the most

interesting and colorful armies of the Renaissance, and when painted

with patience and care will present a satisfying and impressive spectacle

on the wargame table.