MAPPING YOUR SETTINGS

MAPPING YOUR SETTINGS

Q: I want to create

a map as large and

as detailed as the map of

Deepearth

on pages 76

and 77 of the DSG. The

blank maps included at the

back of

the DSG use boxes.

that are too large

for mapping at this scale.

Is there

any way around this?

A: Doug Niles rolled

up into a ball and

thought about this one for

a while. When

he unwound himself, he offered

a solution.

Take the most suitable map

in the

back of the DSG (probably

one of those on

page 127)

and enlarge it using a photocopy

machine. Then, take a straight

edge and

draw a vertical line between

each pair of

vertical lines on the blank

map (these new

lines should bisect the

spaces between the

old lines). Do the same

for the horizontal

lines. You have now doubled

the number

of spaces available for

your subterranean world.

(118.58)

Most DMs have developed a fair degree of

skill in drawing orthographic maps--

the typical, top-view illustration of

corridors, rooms, doorways, and other features of a dungeon

or other setting.

This type of map, like an

architectural blueprint, shows

exact relative sizes of all areas displayed,

and is very useful for

recording distance && direction.

If more than one level of elevation needs

to be displayed, however,

a separate map must be drawn for each

level. Often, the

exact position of an area that runs through

two or more levels,

such as a stairway

or well shaft, is hard to picture when players or

DMs use an assortment of orthographic

maps.

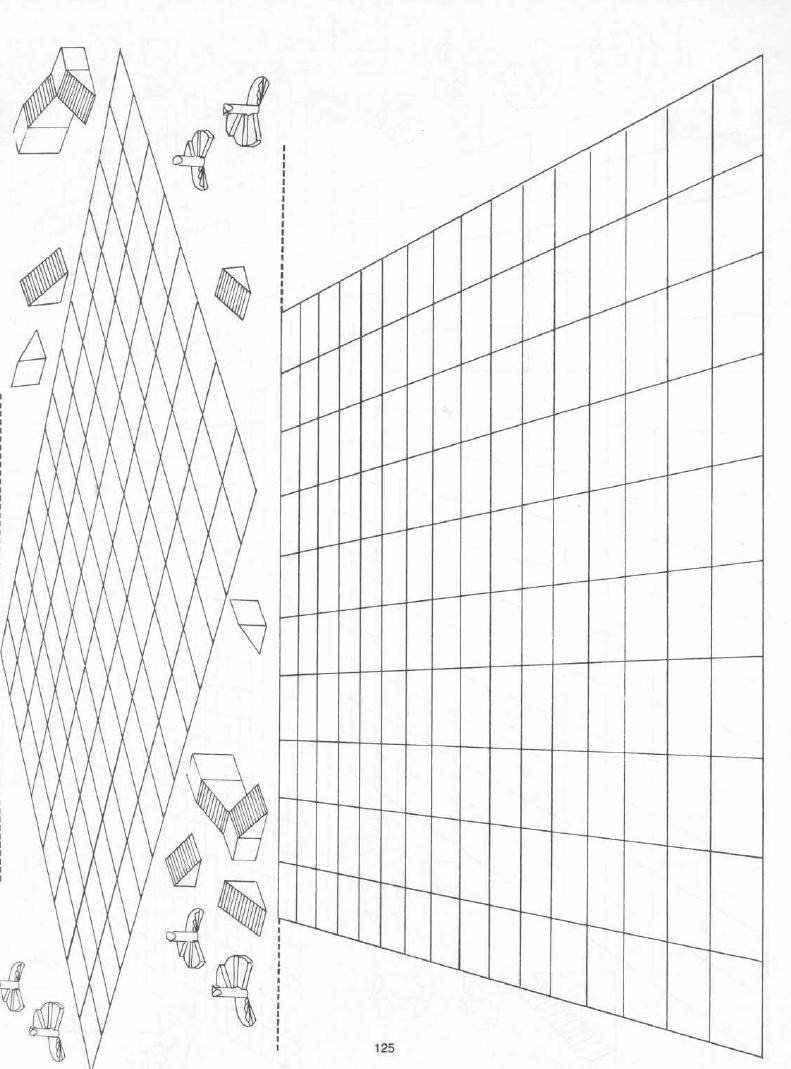

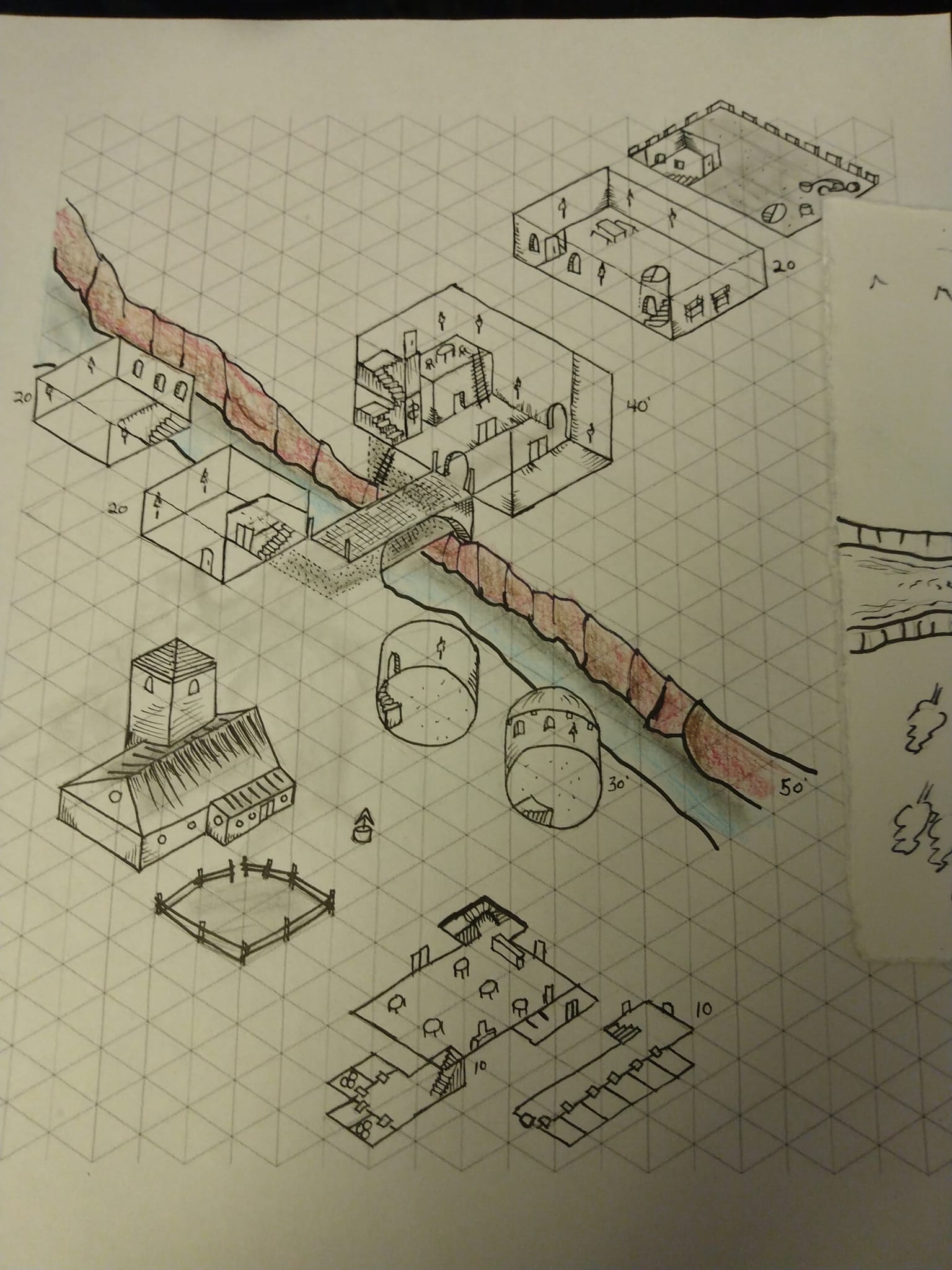

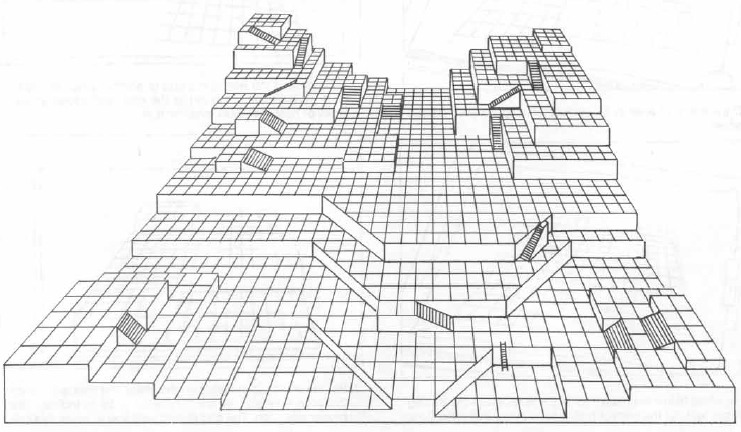

An alternate technique known as perspective

mapping is

explained in this section. A DM willing

to take the time to learn a

few points, and to photocopy one or more

of the perspective grids <>

in the back of this book, will find that

he can prepare detailed and

attractive 3D maps for multi-level settings

above || below ground.

Basic

Mapping Considerations

An effective map is one that communicates

the necessary

info to the people who will use it. This

can often be

accomplished in a few minutes with a pencil

and some scratch

paper.

However, if you have the {time} &&

interest to create attractive,

easily legible maps that accurately convey

a great deal of detail

about your setting, a little more care

is called for. Buy or borrow a

few tools, such as

a straightedge, compass, protractor, and a

template or two. You may also wish to

use a felt-tip or razor-point

pen for drawing, since these make a line

slightly thicker than the

underlying grid. These mapping aids can

greatly improve the

appearance and legibility of your maps.

Perspective

Mapping

Perspective mapping has advantages and

disadvantages

compared to standard orthographic mapping.

On the positive

side, a perspective map conveys the 3D

nature of

a setting much more realistically than

an orthogonal map. The

position of each dungeon

|| castle level relative to all of the

other

levels is much clearer, and the connections

between the levels

are easier to see.

On the other hand, perspective mapping

requires a little more

knowledge of technique than orthographic

mapping. Raised features

on a perspective map, such as staircases,

spiral stairways,

platforms, ramps, and any other 3D details

will

obscure the view of areas immediately

behind them. Also, the

smaller squares to the rear of a perspective

grid tend to cramp

your design if used for areas that need

careful attention to detail.

Finally, a perspective map takes more

time to draw than an orthographic

map.

However, if you have the time and don’t

mind learning a few relatively

simple techniques, you can create maps

that communicate

much more information than simply how

big a room is, or

whether the door is in the north or the

east wall.

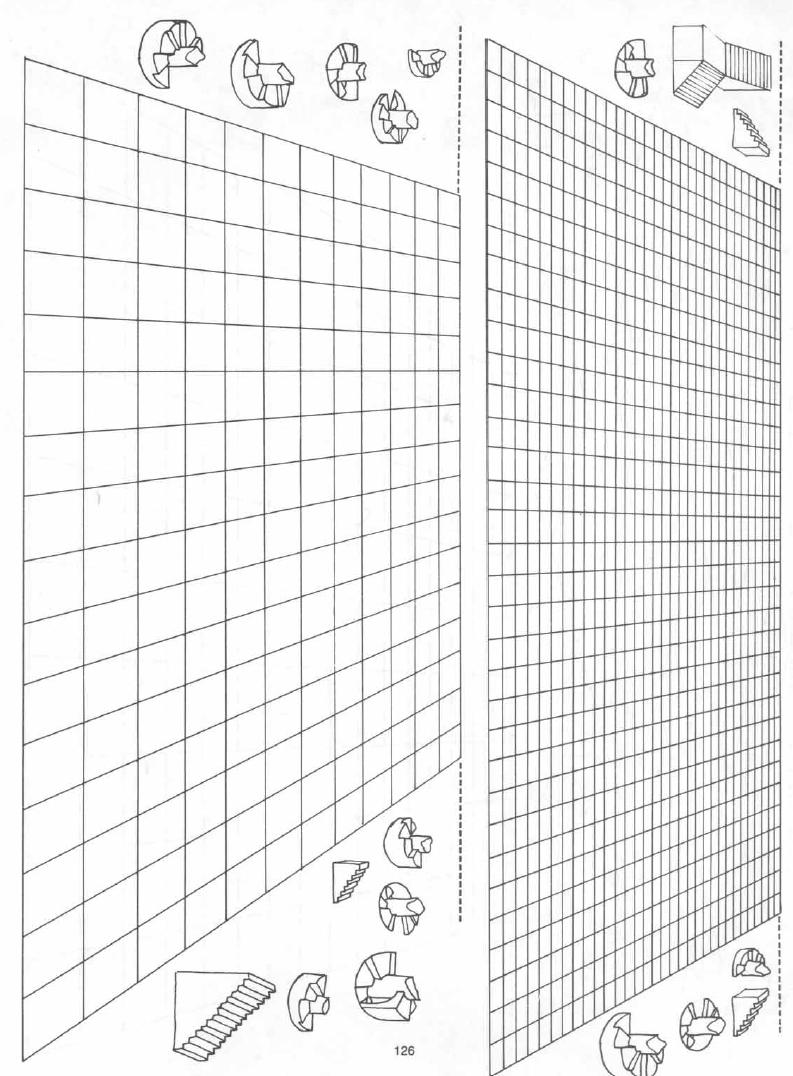

There are two easy ways to start a perspective

map. The first

step in each case is to select a grid

from those provided in this

book. Pick the grid that best displays

the details of your design,

whether it be a castle, tower, dungeon,

or cavern. For example, a

solid, square castle or dungeon requires

one of the square grids

that give approximately equal dimensions

of depth and width. A

longer, narrower grid works better for

a cavern or wall.

1. The first mapping technique requires

you to make a few photocopies <>

of the grid. Permission is hereby granted

for the photocopying

of these grids for personal USE only.

Make one copy for

each floor or level you need, and consider

making a few extras if

you want to do a really careful job. A

photocopier that makes

enlarged copies can

be very helpful.

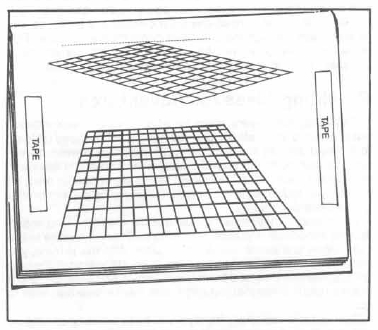

2. The second technique requires

you to buy a tablet of tracing <>

paper. You can then trace portions of

the grid on the tracing

paper and draw in the map details. You

can try to hold the tracing

paper in place over the grid by hand,

or you can tape it into place.

Take precautions before taping, however,

or the tape will eventually

tear the pages of the book or lift up

the print. This will not happen

if the tape holding your tracing paper

is taped to transparent

tape instead of the actual book page.

By permanently placing two

short pieces of clear tape on each grid

page, as in the diagram,

you provide places to fasten the tracing

paper without ruining the

page.

Before you select a grid for your map,

you should think about

the overall shape of the AREA to be designed.

Select a grid that

best matches this overall shape, whether

it is long and narrow or

relatively square. Because raised details

such as stairways

obscure the areas behind them, design

such areas so that they

do not need much detail. For

example, directly behind a tall stairway

you might place a

large, empty room or even an expanse of

solid rock.

Also, because the squares at the rear of

the grid are much

smaller than those in the front, try to

design your most important

and detailed areas toward the front of

the grid. If you like using

raised platforms in your designs, place

those platforms so that

the lower ones are in the front and the

higher ones toward the

rear. It might help to imagine that you

are designing a set for a

stage play, and you want the audience

to be able to see all of the

acting AREA.

Start the design as close to the front

of the grid as possible.

Because the large squares in the front

allow for greater detail,

they should be used for the most intricate

or important areas.

This does not mean that the entrance to

the lair, dungeon, etc.,

has to be placed near the front of the

grid-you might instead

have characters enter the area far to

the rear, and work their way

into the important areas you have detailed

near the front.

If your design has several levels, you

should designate a control

square. This is a single square on the

grid, located roughly in

the center of the area being designed.

It is a good idea to center

the control square under the highest tower

or the midpoint of the

top level of your design. The control

square allows you to line up

the grids for each level, since the control

square on each level is

directly above or below the control squares

on the adjacent

levels.

If each level of your design is approximately

the same shape,

the control square should be the same

square on each of your

grids. If you have made several photocopies

of the grid, simply

hold them up to a light and make sure

all the control squares line

up. If you are using tracing paper to

copy the grid, place a pencil

mark in the control square of the grid

you have chosen in the

book, and then mark that square on your

traced copies.

Once you have established the grid, drawing

a perspective

map is very much like drawing an orthographic

map. The biggest

difference is that the squares making

up the map grid are not true

squares. It may take a little getting

used to, but with practice you

should be able to make perspective maps

as easily as the flatview

variety.

You might find it advantageous to draw

the outer limit of the

design first. This helps you visualize

the overall structure, and

also makes it easier to line up the maps

of the various levels.

Alternatively, you might start with a

huge staircase or centrally

located atrium that includes areas on

several levels.

The symbols that work on an orthographic

map can usually be

translated directly onto a perspective

map. Doors, trapdoors, curtains,

furniture, and many other symbols can

be used just as you

have always used them. The symbols for

certain 3D

objects must be changed slightly, however,

since the

map must portray these objects vertically

as well as horizontally.

Numerous mapping symbols for these 3D

objects have been printed beside the map

grids. You can photocopy,

trace, copy, or cut and paste these onto

your maps. Several

different styles of symbology are presented,

from very simple

types to more elaborate and artistic designs.

You may find it easiest

to use the more basic symbols when you

start out, but you will

probably be surprised at how quickly you

develop the necessary

familiarity to deal with all of these

designs.

When an AREA is designed, and particularly

in the case of an

underground environment

that does not rest on level ground, you

may wish to mimic minor changes in altitude

by cutting your grid

into the appropriate pieces and shifting

the individual pieces up

or down slightly.

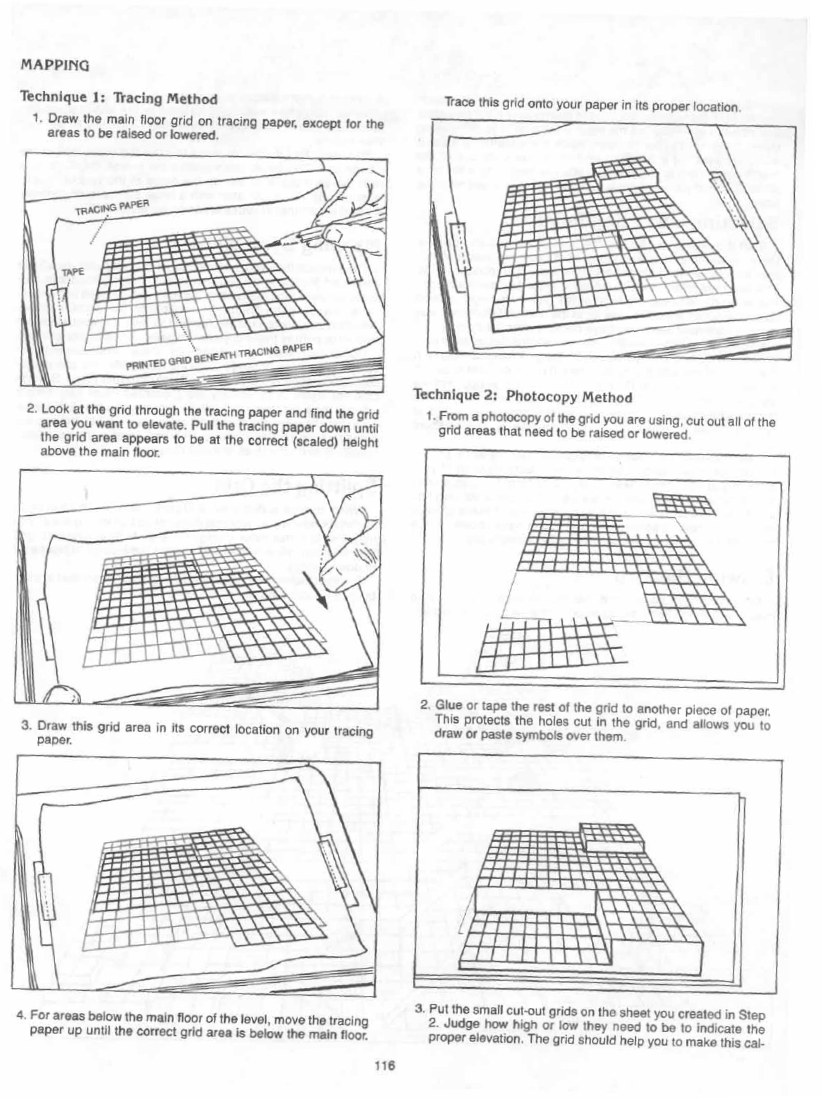

Different techniques for splitting the

grid are described in stepby-

step fashion below.

(continued, from 3, above)

-^-culation. For example, if each square

equals 10 feet, and you

want the platform to be 20 feet above

the main floor, simply measure

a nearby square and put the platform grid

twice that distance

above the cut line.

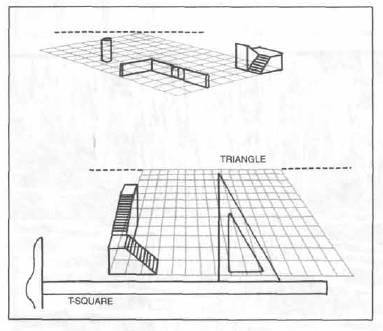

Each sample grid in this book includes

a horizon line.

The purpose of the horizon line is to

help you to view the grid correctly.

In order to correctly orient the grid,

turn it so that the horizon line is horizontal, or level.

The horizon line can also help you to draw

vertical lines on the grid.

Pillars, staircases,

ladders, and other primarily vertical objects should not look as if they

are about to topple.

With a F square, or with a triangle that

includes a 90-degree angle, you can use the horizon line to accurately

draw vertical lines.

If you wish to draw a vertical line, simply

make sure that it is perpendicular to the horizon line.

In a typical campaign world, the DM does

not have {time} to prepare detailed maps

of all the regions that the PCs are likely to visit.

The problem can sometimes be alleviated

by mapping only those areas that will be needed in the immediate future,

but since the PCs’ actions are often unpredictable,

it can be difficult to determine which way they will go next.

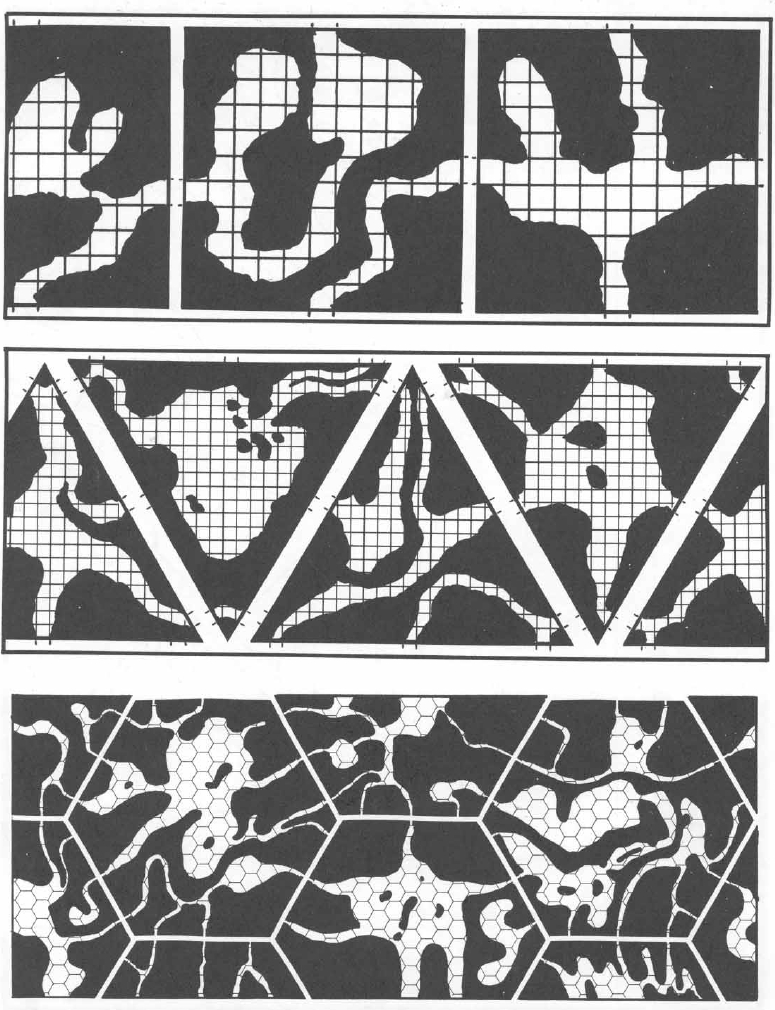

Geomorphic maps, which are particularly

applicable to underground

settings, present another solution to

the problem. Geomorphic

maps are a series of maps created in the

same shape

&& size, with standardized entry

and exit points at various locations

around each map’s edges. A geomorphic

map can be

altered so that any one of its edges abuts

a neighboring

geomorph; consequently, a tremendous #

of combinations

can be created. The advantage to geomorphic

mapping is that

you do not have to map out every square

foot of a massive region.

Instead, you use a combination of geomorphs

to create the areas

needed. Areas that are particularly well-suited

for geomorphic

mapping include most underground settings,

and large cities or

sprawling fortresses on the surface.

A single geomorphic map section should

not be designed to

portray a whole setting. Ideally each

section should create only a

small part of the entire AREA. Then you

can assemble the

geomorphs like the pieces of a puzzle,

and eventually design an

entire, vast AREA, one section at a {time}.

Also, a geomorphic block

may contain several separate adventure

areas; you need not USE

all of these areas.

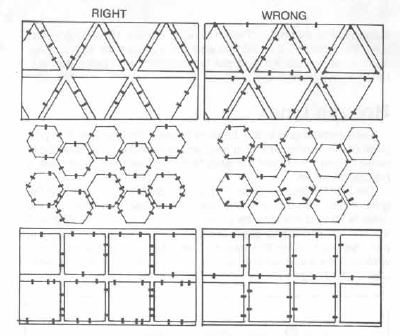

Geomorphic maps can be created as squares,

equilateral triangles,

or hexagons. Squares are the easiest to

use. Whatever

your choice, all of your geomorphs must

be drawn in the same

shape so that they will fit together.

After you determine this

shape, you need to decide what the scale

of your maps will be,

and how many possible points of connection

you will have on

each side.

Triangular geomorphs are limited in that

each map has only

three possible orientations when placed

into a design. Thus, the

number of geomorphs needed is larger than

it is with the other

types, unless you want to repeat the patterns

a great deal.

Hexagonal geomorphs have the greatest

number of potential positions,

but are also slightly more complicated

to draw.

Many mappers consider the square geomorph

to combine the best features of all types.

When you begin to design your geomorphs,

plan how many

possible connections you wish to have

between each map section

and its neighbors. This does not mean

that each geomorph

connection must lead to a through-way,

but it allows you to provide

for plenty of route options.

The scale of your maps should influence

the# of connecting

locations you have on each geomorph. If

each map section

represents a 60 x 60-foot square, you

will probably want no

more than two, and perhaps only one, potential

connection per

side. If the geomorph represents a square

mile of an underground

realm, you

may wishto have as many as six or eight

potential connections on each side of

the map.

The various types of geomorphs, and notations

for marking the

access and egress points on each, are

diagrammed here.

The connections between maps must occur

at a standardized

location on the sides of each geomorph.

For example, you might

have a connection occur in the exact center

of each side, or

include a pair of connections that are

each 1/3 of the distance in

from the edge of the geomorph. Measure

your distances carefully,

since this determines whether or not your

maps line up

properly. Whatever pattern of connections

you use must be symmetrical

to both left and right, or you will not

be able to line up the

map sections.

Once you have established the basic parameters

of your

geomorphs, you can begin to draw as many

maps as you have

the time and interest to do. Each map

should be drawn to the correct

shape and scale.

Although you do not need to make sure that

every possible

connection on each geomorph leads somewhere

(Le., does not

dead-end), at least 75% of them should

provide a means of entry

into another map section. A greater number

of dead-ends dramatically

increases your chances of enclosing whole

sections of

your dungeon and making entry and exit

almost impossible.

Once you have a collection of geomorphs,

you are ready to randomly

generate an AREA

of potentially huge proportions. Of

course, this procedure does not have to

be random--if you feel

that a certain map section would be ideal

for a particular location

in your campaign setting, by all means

put it there. For the most

part, however, you can generate the overall

map of your setting

by making a few die rolls and varying

the placement of your

geomorphs.

You might start by numbering each geomorph

and rolling dice

to determine the placement of each geomorph.

To begin mapping,

roll a die and start with the geomorph

with that number on it.

A geomorphic map section can be placed

in any one of a num-

ber of positions. The number of positions

equals the number of

sides of each map section, so a triangular

section can be placed

in one of three positions, a square in

one of four positions, etc.

Roll a die (a d3, d4, or d6, as appropriate)

to determine which face

of the geomorph is north.

Once you have placed a geomorph, treat

it as a normal part of

your setting map. Allow the PCs to explore

it and map it as they

normally would. If they reach an edge

of the map section, simply

roll a die again to pick a new geomorph

to add to that edge, and

then roll to determine that geomorph’s

orientation (which side is

north). If a connection between the two

matches up, as it usually

will, the PCs can proceed without learning

that they have moved

onto another map section. If the connections

do not line up, the

party simply wanders into a dead end,

and has to find another

path.

By using a variety of geomorphs and making

sure that they are

placed in many different orientations,

you can create a huge

region of well-mapped terrain,

and your players will never know

that they are passing through many of

the same map sections

that they have previously explored.