The Underground Environment

The Underground Environment

Life underground is drastically different

from that aboveground.

Most of these differences are shaped by

the unique limitations

and opportunities of the underground environment.

Several

blessings most surface dwellers take for

granted, such as sunlight

and fresh air,

are in short supply beneath the surface. On the

other hand, water

is usu. plentiful underground--even below

the driest of deserts, if one is willing

to go deep enough--and a

variety of rock && mineral treasures

await the miner who knows

where and how to look.

1. AIR SUPPLY

2. CAVE-INS

3. HYPOTHERMIA

4. MAGNETIC EFFECTS OF LODESTONE

5. NPC REACTIONS TO LONG UNDERGROUND ADVENTURES

Players make the decisions about their

characters’ likes and

dislikes. Henchmen and hirelings, however,

do not have the motivation

that inspires player characters to embark

upon a prolonged

underground expedition.

If NPC companions of the player characters

are expected to

accompany a long underground expedition,

special incentives

may be necessary to persuade the NPCs

to remain underground.

Henchmen and hireling loyalty should be

checked as soon as

they are informed of the nature of the

expedition, with a normal

Loyalty

Check as explained on DMG pages 36 and 37. The check

is required whenever a party plans to

spend a week or more

underground. It is not necessary for dwarf,

gnome, or drow

NPCs.

There are two additional modifiers that

may apply to Loyalty

Checks underground. A -5% applies to the

d100 roll for every

week that the party plans to spend underground.

Also, if the

NPCs learn that they have been deceived

about the duration or

destination of the expedition, or are

told when it is too late for

them to avoid it, an additional -10% modifier

applies.

For example, if the PCs lead a group of

henchmen and hirelings

across a blazing desert, then announce

that they will

explore a dungeon and plan to be underground

for a month, the

NPC Loyalty Check is made with a -20%

modifier for the month

underground and an additional -1 0% modifier

for deceiving the

NPCs.

Each NPC, whether henchman or hireling,

must be checked

with a separate roll. The DM should note

all of the NPCs who fail

the check.

Afailure on this Loyalty Check means that

the NPC does everything

possible, short of risking his life, to

avoid going on the mission.

If he is compelled to accompany the party

by circumstances

or the PCs, he is considered to be unsteady

An unsteady character becomes unsettled

by long periods

underground, away from sunlight and fresh

air. His mind begins

to slip, slowly at first, and finally

in a fashion that can prove disastrous

for himself and his companions.

The unsteady character begins to suffer

ill effects following the

first week underground. His morale is

lowered by 10% for all

Morale and Loyalty Checks. He acts nervous

and jumpy. Following

each additional week of underground exposure,

another Loyalty

Check is rolled for the character. As

soon as one of these

fails, he becomes completely irrational.

Roll ld100 and check the

NPC’s reaction on Table 20: Unsteady NPC

Reactions.

Table 20: UNSTEADY NPC REACTIONS

| d100 Roll | Reaction |

| 01-20 | Character runs screaming toward the surface to the limits of his Endurance |

| 21-55 | Character attacks nearby PC |

| 56-85 | Character attempts to sneak away quietly, as soon as possible |

| 86-00 | Charater freezes in place, not reacting or moving |

Effects determined on this table last until

the character is slain,

or returned to the surface. In the latter

case, the character must

spend ld6 weeks above ground before a

Wisdom Check is rolled

for him. If this check succeeds, the character

has recovered. If it

fails, the character is permanently afflicted

with the appropriate

irrational behavior.

| Features of the Underground Game | Nature of the Underground Environment and its Denizens | A Brief History of Underground Cultures | Underground Geography:

Domains in Three Dimensions |

Theories on the Nature of the Underdark |

| The Underground Environment | - | - | - | DSG |

AD&D@

game worlds offer a wide variety of underground passageways

of both natural and constructed origin.

Many of these

areas are inhabited by creatures that

resent intrusions into their

homes. This creates a vast underground

ecosystem that is far

more extensive than that of the real world.

While the existence of such an ecosystem

in a game does not

require any explanation beyond the fact

that it makes for a fun

campaign world, several logical reasons

justify the vast and wellpopulated

regions of the underearth.

In a world where flying creatures are not

uncommon

and potent magical spells can magnify

the effects of a battery of

heavy cannon, underground fortifications

make sense. In some

ways, a dungeon

is a more secure position than a castle. Consider

the weakness of a historical castle to

aerial attacks or earthquake

spells, for example. A dungeon or underground

fortification is virtually impervious

to aerial attacks. Of course,

spells such as earthquake can cause damage

to underground

areas as well as to buildings on the surface,

but identifying the

target for the spell is difficult when

the dungeon lies well beneath

the ground.

A dungeon can also be held by a much smaller

group of

defenders than even a very well-designed

surface fortress, since

accesss to a dungeon is much more limited.

Although the attacks

of burrowing creatures such as umber hulks,

landsharks, and

xorn still present a menace, such creatures

are rarely marshalled

into an army. In any event, if a force

of such burrowers were collected,

it would present as much of a threat to

a castle as to a

dungeon.

The efforts of miners also threaten dungeons

and castles.

However, while a castle is likely to have

only a few dozen feet of

stone to block excavations, a dungeon

can be built at any depth.

The farther it is from the surface, the

more effort is required to

excavate an access for an attacking army.

Unlike castledefenders,

dungeon-dwellers do not have to maintain

a garrison

of troops to hold the wall, so they are

much more likely to have a

reserve of troops available to combat

a sudden break-in.

This defensibility probably accounts for

the survival of the

races of the drow and duergar. After suffering

nearly total defeat

at the hands of their enemies upon the

surface, the pitiful survivors

of these races slunk into the Underdark.

There they were

able to withstand the final assaults against

them, and managed

to survive and finally prosper. Although

these creatures are now

so fearful of sunlight that they pose

little threat to surface dwellers,

they are almost completely unassailable

in their underground

lairs. Thus, an uneasy balance is maintained.

Mining:

The proliferation of races such as dwarves

and

gnomes, whose economies rely almost entirely

upon their skill as

miners, accounts for a great deal of underground

excavation.

Indeed, many areas originally excavated

as mines have been

converted to underground fortresses, prisons,

or monster lairs. In

addition to these races, a number of monsters,

including purple

worms, umber hulks, and anhkhegs, burrow

throughout the

earth, creating passageways that can be

used by smaller creatures.

The combination of this great amount of

mining activity with the

burrowing of subterranean monsters has

created a network of

connecting passages that link nearly all

of the major subterra-

nean cavern networks. Thousands of huge

natural limestone

caverns-many of them over 100 miles long-are

now connected

by these tunnels.

Gravity: Underground

passages in the fantasy world are vast,

with many points of access

and egress on the surface. Often

these points are simply holes sinking

into the labyrinthine passages

below. Throughout the centuries, many

creatures fell into

these holes and were unable to get out

again. If food and the

other essentials of life were available,

some of them managed to

prosper underground. Gradually, the ways

of the sunlit world

were forgotten, and the creatures’ descendents

adapted themselves

more completely to the ways of the dark

world.

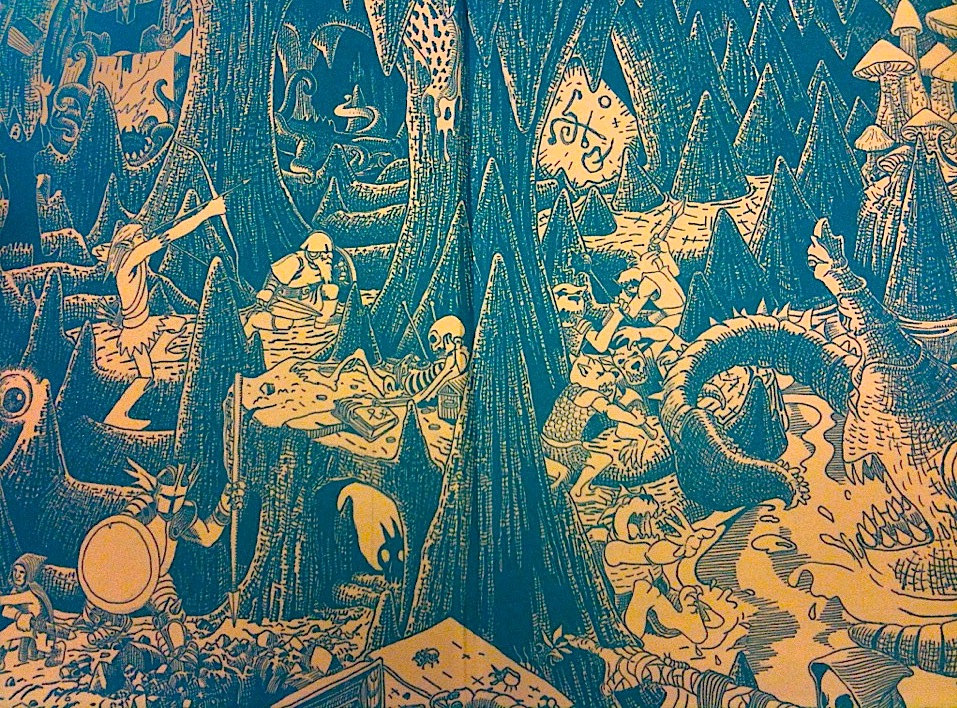

Features

of the Underground Game

| Control | Danger | Alienness | Frontiers | Back to Basics |

| The Underground Environment: DM's Section | - | - | - | DSG |

A RPG set in the narrow spaces of the

Underdark

occurs in an entirely different type of

environment from that of a

wilderness or city. In addition, the underground

game also contains

elements of story design, player character

decisionmaking,

and game limitations that are far different

from those in a

surface setting.

Control: In

an underground game, particularly

with lower level

PCs, the DM exerts a great deal of control

over the

options and challenges facing the players.

If the adventure

begins in a subterranean room with two

corridors leading from it,

the characters have only three real options:

stay put, or explore

one of the two corridors. Thus, the DM

needs only to prepare for a

few courses of PC action.

If you have designed an essential encounter,

you can easily

create a situation that leaves the PCs

no option but to tackle this

encounter. Even with several paths available,

you can place key

encounters in centrally located rooms

that PCs are almost certain

to visit regardless of the routes they

choose.

You can easily determine the tactics of

monsters and NPCs,

planning these encounters well in advance

because you know

that the party can only approach from

a limited number of directions.

You can rig alarms and set up ambushes

with confidence.

Of course, intelligent and creative play

can always undo many a

DM-rigged surprise!

Players may also have an easier time with

the underground

game, for many of the same reasons. The

very narrowness of

available options makes the decision-making

process easier-a

fact that is appreciated by beginning

players, in particular. Combat

tactics can be simplified by the confining

terrain of the typical

underground setting. PCs who find themselves

outnumbered

can hold a better defensive position in

a doorway or a IO-footwide-

corridor than they could in a wilderness

clearing.

Danger: Imaginary

danger is a key ingredient of all adventure

RPGs, and the dangers associated with

the underground

are some of the most fascinating and enjoyable

to play.

The darkness

of the underworld combines with the tight passageways

and distance from possible succor to create

an atmosphere

of intensity and excitement that is virtually

unheard-of in a

wooded or city setting.

The dangers of the underground touch fears

common to us all.

Caves and old mines are traditionally

regarded as dangerous

places where only experts dare tread.

The game allows players to

role play exploration of these forbidden

reaches with nothing at

risk save an imaginary character.

The depths of the earth have often been

associated with reallife

dangers such as volcanoes and earthquakes.

In addition,

there is a vast wealth of mythological

material about the foul

sources of evil lurking below the surface

of the world. When

game players enter these regions, they

have an opportunity to

role play confrontations with lurking

sources of evil in a foreign

and fantastic environment.

The players’ unfamiliarity with the underground

environment can add to the sense of wonder

created by adventuring

there. The combination of dark, mysterious

locations and

bizarre, unknown creatures give the AD&D@

game much of its

appeal. Nowhere are these features more

apparent than in the

underground.

The information included here enable the

DM to describe

underground regions in enough detail to

satisfy the players’ curiosity.

Although the underground should remain

unique and mysterious

to the players, the DM needs a great deal

of information in

order to effectively run the environment

as a believable and interesting

locale.

Frontiers:

The term frontier usually denotes a region where

the controlling influence of civilization

ceases and the realms of

wilderness

begin. It can also describe a boundary where the influence

of one government, society, or culture

ends and that of

another begins. Both of these meanings

apply to various regions

of the underworld.

The desire to conquer frontiers is almost

universal. In a world

where the reaches below the earth’s surface

present opportunities

for exploration and conquest, frontiers

are naturally

extended in that direction. In fact, characters

living in the center

of a large civilized area often find that

the frontier below their feet

is a great deal more accessible, and perhaps

more challenging,

than any of the farthest frontiers of

the national boundaries.

Expansion of the subterranean frontier

includes missions of

exploration, scouting, plunder, and conquest.

In each case, characters

push beyond the known limits of their

world into unexplored

(or at least, poorly explored) reaches.

Knowledge that they

carry back to the surface is valuable

information to their king or

other ruling body. In fact, the desire

to expand a frontier is often

sufficient motivation for a group of characters

to embark upon an

expedition.

As mentioned in the introduction, most

garners begin their careers with some

kind of underground exploration,

usually involving a dungeon

stocked with a few nasty monsters

and some worthwhile treasures. Many players

continue

with this type of game through increasingly

advanced levels,

while others soon tire of the routine

and either move on to a different

type of setting, such as city or wilderness

adventuring, or give

up gaming altogether.

Perhaps the most important point is that

underground adventure

does not need to be a routine of exploring

dungeons, slaying,

and looting. The realms of the Underdark

are populated with civilizations

as old or older than any on the surface.

These civilizations

are a rich source of challenge-their odd,

strongly

motivated NPCs can be used to create encounters

every bit as

sophisticated and challenging as role

playing in the court of the

High King.

Many players whose interests have moved

beyond the area of

underground adventures are not bored with

the underearth per

se, but with the type of adventures that

the DM created during

their early dungeoneering experiences.

In many cases, the DM

had little more experience with the game

than the players, and

nobody knew that there were other aspects

to the game besides

hacking and slashing one’s way through

a dungeon.

These players can often be drawn back into

the dungeon with a

more mature type of adventure, utilizing

a strong story line and

detailed NPCs to generate interest and

motivation among the

players. A DM familiar with the vast reaches

of the Underdark can

create underground adventures that challenge

any player. Of

course, many players enjoy the hack-and-slash

type of adventure,

and there is probably no better setting

for this than a dark,

dank, dungeon full of mysterious beasts

and devious traps. It is

important to realize, however, that if

the players are ready to

move on to a new type of gaming, it is

not necessary to leave the

dungeon for innovative adventures.

Player characters who have spent their

last few levels out of

doors or in a city often enjoy the change

associated with a return

to a dungeon adventures. Variety in all

aspects of the game is crucial

to maintaining both player and DM interest.

This variety can

be achieved by utilizing different settings,

as well as varying story

lines and conflicts.

Nature

of the Underground Environment and its Denizens

| Balance of Power | Alignment | Philosophy | Distance from the Surface | Ecology |

| The Underground Environment: DM's Section | - | - | - | DSG |

The following pages describe the individual

races && cultures

of the underground,

and introduce || enlarge existing descriptions

of unintelligent creatures that dwell

there as well. A few generalizations

that apply to all of the races living

beyond the Sun’s

reach are presented here.

Each race of the underearth has unique

characteristics. The races of the drow,

duergar, svirfneblin, mind

flayers, myconids, kuo-toa, etc., have

existed together in

crowded underground chambers for centuries

in spite of their differences.

Whenever the DM allows PC intrusion into

these

realms, it is recommended that they find

these cultures in a precarious

balance of power. Because this balance

is unstable, the

arrival of a group of characters from

the surface may well be

enough to upset the equilibrium.

Like surface dwellers, the races of the

underground stake out

territorial claims, and generally attempt

to hold on to their collections

of caverns, tunnels, and underground islands

with all of

their means. Land is even more precious

to underworld folk than

it is to surface dwellers, since solid

rock often prevents a displaced

race from moving freely to another location.

Alignment:

Although all of the alignments and philosophies

known to intelligent creatures are found

among the deepdwellers,

a cursory examination of these races shows

a tendency

toward evil among the majority of them.

The reasons for this are

not entirely clear, although several lines

of conjecture have been

suggested.

It is known, for example, that the races

of the drow elves and

the kuo-toa

originally dwelt upon the surface of the world. These

races were driven underground as a direct

result of warfare

waged, and lost, against the united forces

of the current surface

dwellers. The actual details of these

conflicts have been lost to

time, but it seems a reasonable assumption

that the fundamental

conflict was a clash between good and

evil. Evil, losing, was banished

to the less appealing locations underground.

Of course, this oversimplifies the situation,

since there are evil

races and cultures remaining on the surface,

as well as bastions

of good existing underground. However,

the passage of time

since the ancient conflicts naturally

resulted in gradual changes

of the alignments and philosophies of

entire populations. Also,

evil governments may have worked out alliances

with the forces

of good, allowing them to coexist as allies

during those tumultuous

times.

Another theory attempting to explain the

proliferation of evil

creatures in the deep makes a connection

between these CUItures

and the denizens of the lower planes.

While it is certain that

the evil creatures of the Underdark worship

the potent forces of

evil ruling the lower planes, no concrete

evidence indicates that

the depth of the environment causes the

connection. It is quite

possible that the creatures of the Underdark

worship these evil

deities because of a previously existing

evil alignment.

The latter explanation might have the

most merit when applied

to the oldest of the underground races-those

with no known period

of surface-dwelling. Mind flayers and

derro fall into this category,

and it seems reasonable to assume that

these creatures

adopted their thoroughly evil alignments

long ago through the

dire influence of some dark power.

Philosophy:

Every underground culture has developed distinct

philosophies. Each culture has several

things in common

with other races living under the surface,

however.

A common feature of these peoples is an

absence of, and little

appreciation for, a sense of humor. Perhaps

because of the

sobering danger presented by the environment

itself-the tons of

rock poised overhead, the chance of asphyxiation

or floodthese

beings tend to see life as very serious

business. Their literature

and art almost universally portrays death

as an

omnipresent force. Laughter is almost

unheard of among the Cultures

of the deep reaches.

Many of these races are chaotic in nature,

but this alignment is

reflected mainly in large-group organization

and coordination.

The individuals of each race, whether

lawful or chaotic, tend to be

very disciplined in their personal habits

and social lives. No doubt

the scarcity of many resources taken for

granted on the surfacemost

notably air-has forced these creatures

to adopt a more

careful approach to life.

When art is created in the Underdark, it

usually has a function

beyond artistic merit. Sculpture is usually

worked into support

columns or sturdy arches, serving to decorate

those necessary

pieces of underground architecture. Solemn

vows or formal introductions

may be presented through songs, thus using

the

medium of music to help accomplish something

perceived as

useful. Encyclopedias are considered one

of the highest forms of

literature.

Waste, whether of food, material, or energy,

is deplored and

often punished severely. Again, the constraints

of the environment

can easily explain this value. Air is

a valuable resource, and

the control of its use, particularly regarding

fires, is a common

feature of underground law.

Underground races perceive the concept

of time differently

than surface dwellers. With no changing

of day into night or summer

into winter, a certain timelessness is

reflected in the philosophy

of the underground races. Often, the truest

indicator of time

is the aging of creatures and plants.

Even such long-term measures

of time have little meaning. A common

tale of the deep

races speaks of a young man from the surface

who was captured

and sentenced to immediate execution,

but died of old age in his

cell before the sentence was carried out.

Creatures raised in the underground are

usually very stubborn

and resistant to change. The most conservative

of the surface

governments would seem to fluctuate radically

and whimsically

by comparison. Perhaps this narrow-mindedness

arises also

from the environment-with solid rock all

around, the options

available when a decision is required

are often seriously limited.

Distance from

the Surface: The subterranean reaches

extend from the entrances to caverns,

tunnels, mines, and ventilation

shafts on the surface to the deepest hollowed-out

regions

of the Underdark.

The exact depth of the lowest areas is

unknown, but can be measured in tens of

miles. The characteristics

of a given area are determined to a great

extent by how far

below the surface it lies.

Resources acquired from the surface

are common only in the

top several hundred feet of the Underdark,

except in those areas

where gravity can be used to move resources

deeper without too

much difficulty. Wood is probably the

most common of the

surface-based resources to be transported

underground, since it

is needed to shore up tunnels or bridges.

Occasionally wood can

be transported to great depths with the

aid of an underground

stream or river of significant depth.

The timber is harvested on

the surface and then simply thrown into

the water, where it flows

downstream to the desired location. There

it is retrieved and

transported to its final destination.

Although wood can be carried

a mile or more below the surface this

way, few waterways have

sufficient flow to carry the wood without

jamming, so this tactic is

only employed in certain areas.

Certain rare species of fungi with solid,

woody stems also grow

underground. When they can be located,

these are often harvested

for use as wood.

Food and slaves are additional resources

occasionally harvested

by the denizens of the Underdark. Slaves

and food that is

taken on the hoof are generally forced

to move under their own

power into the depths of the earth. Most

creatures living underground

do not grow crops or maintain herds, preferring

instead to

raid food stores collected by the surface

dwellers.

Another characteristic at least partially

influenced by distance

from the surface is the degree of similarity

to humans possessed

by creatures of the Underdark. This does

not apply to individual

creatures encountered in dungeons so much

as to the cities and

cultural centers of more advanced civilizations.

While the homelands

of the drow, duergar, and svirfneblin

are very deep beneath

the surface, the domains of the much more

alien mind flayers and

aboleths are even deeper.

Ecology: The

ecology of the underground environment has

developed very differently from that of

the surface world. The

foundation of life on the surface is sunlight,

which the underworld

completely lacks. A second element surface

dwellers take for

granted is air

supply, which is much more vulnerable underground.

Consequently, underground life has adapted

to the lack

of sunlight, and does not rely on an unlimited

supply of air.

The underground food chain begins with

many types of fungi,

lichens, and molds that grow without benefit

of sunlight. Herbivorous

creatures such as rothe and cave pigs

have adapted to life

underground by subsisting on these plants.

Intelligent creatures

have domesticated these herbivores, thus

insuring a supply of

fresh meat. As on the surface, unintelligent

creatures generally

eat what they can catch.

Certain unusual life forms have developed

underground and

manage to subsist on diets of stone, gems,

or minerals. These life

forms are quite alien to most creatures,

and generally do not

occupy a place in the food chain. Creatures

that subsist on such

fare are believed to be inedible to carnivorous

or omnivorous

hunters. Another common underground creature

is the scavenger,

which lives off carrion, garbage, and

offal. These creatures

occupy a very minor place in the food

chain, since few carnivores

find them palatable.

Subterranean life forms have evolved an

ecology that does not

depend on sunlight. Creatures living closer

to the surface, however,

often benefit from the comparatively plentiful

surface food

by collecting plants and animals in nocturnal

raids to supplement

their supplies. Most creatures that live

close enough to emerge

from their lairs and return to them in

a single night prefer this

means of subsistence.

Oxygen is a matter of primary concern,

for it must be circulated

even to the deepest reaches of the Underdark,

or the inhabitants

of the deep will suffer. Common rumors

speak of huge shafts that

plummet many miles straight down in arctic

regions until they

reach an area inhabited by an underground

culture. Cold air naturally

tends to sink into these shafts. Underground

races use

geothermal heat to warm the air and send

it rising through different

areas of their domain. Eventually it emerges

through

dungeon and cavern entrances. This is

a natural process; no

forced air movement is necessary. However,

localized pockets of

stagnant air may occur in this system

unless steps are taken to

improve circulation.

68

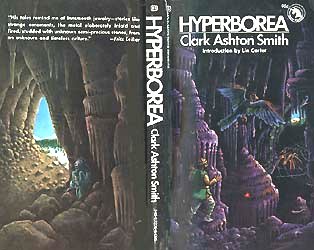

A Brief History of Underground Cultures

Creatures have dwelt in the realms below

for nearly as long as

they have walked the regions of sunlight.

Although the exact

details of underground life are a matter

of individual campaign design,

a rough overview of the major underground

populations is given here.

Certain intelligent creatures of the underearth

have no memory,

nor any recorded history, of existence

outside of their sunless

domains. It seems logical to assume that

these races have lived

underground for as long as they have existed

in their present

forms.

Five distinct cultures have been identified

as dating back to

ancient times in the underground. Two

of these--the jermalaine and

the myconids--have spread through virtually

all of the underground

realms, living in groups that vary from

small and isolated

communities to vast cities.

The jermalaine

were responsible for

creating most of the small, narrow tunnels

that originally connected

many widely separated caverns. Although

the tunnels

excavated by jermalaine were too small

to allow passage to most

other creatures, they served as initial

routes which were later

expanded and organized by other underground

dwellers.

The race of fungus-men,

or myconids, has branches in most of

the deeper areas of the underground. Basically

peaceful, the

early myconids were nonetheless capable

of defending themselves

against the depredations of the jermalaine,

and the two

races learned to coexist with little friction.

Since their food

sources differ, the two races were not

forced to fight for the same

ecological niche.

Three other races seem to have existed

forever under the

ground, but their numbers are much more

localized and concentrated.

The aboleth,

evil creatures of extremely high Intelligence

and advanced culture, live in the deepest

regions of the underearth.

Although capable of functioning in an

airy environment,

aboleth much prefer the dark reaches of

subterranean waterways

for their domains. The aboleth population

is concentrated in

sprawling cities located on the floor

of the Darksea-the vast

underground ocean that is the final resting

place of underground

water.

Because most of the other intelligent

races inhabiting the

Underdark are incapable of living underwater,

the aboleth have

developed their cities and culture with

little interference from

other races. Aboleth are ineffective outside

of water, however;

they are unable to extend their influence

throughout the rest of

the dark domains.

The cloakers

are another culture that has dwelt underground

since time immemorial. So alien that few

other creatures can

communicate with or understand them, the

cloakers live in small

pockets of caverns and tunnels. They often

seem to move into

areas that have been excavated or constructed

by other creatures,

driving the original inhabitants away

with deadly persistence.

Mind flayers

(illithids) are the fifth of the original known underground

cultures. It is thought that the mind

flayers at one time

controlled vast reaches of the underground

domains, and were

feared throughout the lands of darkness.

Their extremely high

Intelligence and fearsome combat ability

allowed the illithids to

move wherever they pleased and take whatever

they wanted, for

none of the other original underground

races could stand up to

them. Only the very low reproductive rate

of the mind flayers prevented

them from gaining control over the entire

Underdark

world.

The illithids have been the victims of

numerous race wars initiated

by other underground dwellers who fear

their great powers.

These wars have driven the mind flayers

into deep and hidden

69

realms, where they are virtually unassailable.

Although warfare

was not unheard of among the cultures,

these five races lived for

millenia in relative balance in the deep

reaches under the earth.

The jermalaine and myconid dwellings were

widespread, while

the aboleth, cloaker, and mindflayer cultures

were much more

localized.

The Alignment

Wars: Then came the great Alignment

Wars. These were actually all a

part of a single grand conflict that spanned

centuries, with occasional

truces that lasted a few decades. The

Alignment Wars

were characterized by great interracial

cooperation and intraracial

combat. The sides were determined not

by race, but by alignment.

Thus, elves,

dwarves, and men of good alignment united to

fight elves, dwarves, and men of evil

alignment. The wars

extended to the seas, where the flourishing

race of kuo-toa chose

to align with the forces of evil and fight

against the marine creatures

of good.

All of these evil creatures bore an intense

dislike for the sun,

and thus their expansion halted at the

mouths of their tunnels and

caves. Rarely would an individual from

one of these races venture

onto the surface, even in the dark of

a moon less night.

Rarely, also, would any surface-dweller

dare the inky blackness

of the world below.

Over the centuries, the forces of good

slowly drove back their

evil foes. Hatred and slaughter prevailed

as creatures of evil were

slain solely on the basis of their alignment.

Great battles were

fought, and eventually the remnants of

the forces of evil had to

acknowledge complete defeat. Bitterly,

these survivors sought

shelter underground and prepared for a

final battle. The drow

elves and gray dwarves (or duergar) moved

underground in great

numbers. The skills they had developed

through centuries of

warfare allowed them to overcome the prior

tenants of the underground.

Likewise, the kuo-toa moved under the

surfaces of the seas

and into subterranean waterways to escape

the genocide of the

Alignment Wars. Tired of the unceasing

conflict, the victors abandoned

their pursuit of the vanquished. Soon

the grand alliance

faded, and once again new sources of evil

appeared on the surface.

Today, little evidence remains that the

forces of good once

held sway over the entire surface world.

Below, warfare again raged, but the newly

arriving races were

able to carve out niches for themselves

in the Underdark. The

domains of the mind flayers and cloakers

were severely reduced

as drow and duergar forces seized caverns

and tunnels. The kuotoa

branched out and claimed many small, dispersed

areas for

themselves. Jermalaine and myconids continued

to prosper,

although they were crowded somewhat by

the immigrants. Only

the aboleths, serenely evil and complacent

in their deep retreats,

were left undisturbed by this transition.

As tunnels and caverns were expanded through

the efforts of

these cultures, many cubic miles of rock

were moved. This excavation,

coupled with the efforts of powerful spell-casters,

opened

gateways from the underworld to several

other planes. The connection

to the Plane of Earth was (and continues

to be) the

strongest one, and many denizens of the

underworld can call

upon creatures from that plane at will.

Additionally, connections

to the lower planes and their insidious

evil developed. Where volcanic

rock bubbled or underground waterways

flowed, doors

were opened to the Planes of Fire and

Water, respectively.

Although creatures from these planes only

represent a small

minority of the population of the underworld,

the interplanar doorways

are not uncommon. Often, adventurers can

discern the

proximity of a gate to another plane by

an unusually high population

of that plane’s denizens.

Two other cultures intruded upon the realms

of the Underdark

during the following centuries.

A race of gnomes was so motivated

by their lust for gems that they adapted

completely to life

underground. These deep

gnomes, or svirfneblin, are one of the

few underground cultures with tendencies

toward good alignment.

And finally, the pech arrived, apparently

emigrating to the

deep reaches from another plane-perhaps

the Plane of Earth.

Like the gnomes, they were drawn by a

desire for mineral wealth,

and soon developed an unsurpassed skill

at working stone. In

many cases, these skilled miners were

able to excavate their living

quarters from the bedrock itself.

The most recent arrival among the ranks

of the underground

cultures are the derro.

These small, dwarf-like wretches seem to

have grown from interbreeding between

duergar and other unidentified

but vaguely human races.

As is only natural in an area with little

space, food, and air, savage

warfare commonly erupts between the races

crowding the

realms beneath the ground. These wars

have been waged since

the drow and duergar first began their

retreat beneath the surface,

and they continue with the same savagery

today. As a direct

result of these wars, areas that were

once overpopulated are now

desolate wilderness, and the underground

populations have

been whittled away to small, isolated

communities.

Today small, civilized pockets of the drow,

duergar, myconids,

derro, pech, cloakers, mind flayers, and

jermalaine are spread

throughout the vast reaches of the underworld.

Between these

pockets, large stretches of uninhabited

or monster-inhabited tunnels

and caverns create a complicated maze.

Below, in the still

waters of the Darksea, the aboleth retain

their age-old control.

UNDERGROUND GEOGRAPHY:

DOMAINS IN THREE DIMENSIONS

| Surface Terrain | Temperature | Humidity | Size | Origin |

| - | - | Access and Egress | - | - |

| The Underground Environment: DM's Section | - | - | - | DSG |

Although most of the underearth is filled

with solid rock, dirt, or

lava, the total AREA of all the caverns,

dungeons,

and tunnels

equal the ground area of a large nation.

These accessible areas

are the underground world that awaits

the players. It is important

that the layout and geography of this

world are well conceived

and thoroughly understood by the DM.

There is reason to believe that the regions

of habitable underground

terrain extend underneath much of the

campaign world. It

would certainly be impractical to try

to map out an entire world’s

worth of caverns and dungeons, however!

The DM should handle

the creation of an entire underground

world on a campaign-bycampaign

basis.

This section details a typical area of

underground geography

that a DM might find suitable to place

underneath his aboveground

campaign world. The area described is

about 1,000 miles

in diameter and several dozen miles in

depth. The basic patterns

of domains and their interrelationships

can easily be adapted to

fit a DM’s needs.

This AREA includes individual holdings

of all of the common

underground cultures, as well as all of

the common underground

terrain types.

The factors governing the types of underground

areas in a

region are not as complex as they are

on the surface, and thus

the development of such regions is easier

for the DM to plan and

control. Several elements do come into

play, however, and they

are discussed individually:

Surface Terrain

The land or water above an

underground region influences the

geography found below. A

network of tunnels or caverns located

beneath a body of water

is nearly always water-filled. If not, a

rationale must be developed

to explain the presence of air. Powerful

magic can hold the water

at bay, but such enchantments

must be permanent. Air pockets

may be trapped in dead-end cor-

ridors, but such air cannot

circulate and hence is stale and of limited

use for air-breathing creatures.

Even

underground areas located below dry land may be filled

with water. If the region

receives a lot of rainfall or is extremely

flat, water usually soaks

into the ground rather than flowing away.

All areas contain a water

table-a level below which all openings

are filled with water. Unless

underground waterways provide

steady drainage, the water

table can make entire stretches of

caverns and tunnels uninhabitable.

When

an underground domain occurs beneath mountains, it

may contain a series of

dungeons or caverns that are actually

higher in altitude than

many surrounding lands. Explorers in such

may move deeper and deeper

into the earth, possibly riding

along the current of a river,

and abruptly return to the surface at

the base of the mountain

range.

Mountains

and other areas of solid granite are much less likely

to be penetrated by caves

than are the vast expanses of limestone

bedrock that lie beneath

much of the plains and forests of

the surface. These areas,

which were once seabeds, are the

most susceptible to natural

cave formations. Of course, underground

areas that have been excavated

can be discovered anywhere,

regardless of rock type.

The nature of a particular

underground region is often determined

by the prevalence of nearby

heat sources. When geothermal

energy is present, caverns

tend to be more crowded with

subterranean plants than

cooler regions are.

Creatures of intelligent

underground races, particularly the

drow

and the duergar, seek out these warmer caverns for their

lairs and cities. Thus the

chance of encountering intelligent denizens

is significantly higher

around sources of underground heat.

Warm temperatures also serve

to circulate air, since heated air

tends to rise toward the

surface and cool, fresh air is drawn in to

replace it. Although this

natural convection is slow and somewhat

inefficient, intelligent

races often excavate ventilation tunnels to

exploit it. Areas thus modified

tend to have a good supply of fresh

air.

The amount of moisture in

a cavern affects the stone of the

walls, as well as the habitability

of the area. If a cave dries up, its

stalactites, stalagmites,

and all exposed surfaces grow extremely

brittle and eventually turn

to dust.

The combination of high humidity

and warm temperatures creates

a steamy environment highly

prized by certain scavengers.

The rock in such areas tends

to be very slippery, and is often

coated with lichen, mold,

or other slimy matter. Underground

areas of extremely low humidity,

regardless of temperature, tend

to be very dusty.

Water

flowing through an AREA constantly erodes its bed, so the

area itself is always changing.

Such erosion often leads to caveins

and rock slides, hazards

not common in drier regions.

The expanse of an area hollowed

out from rock determines a

great many of its characteristics.

Most obvious are the physical

limitations placed upon

the sizes of creatures that could be

encountered there. A group

of halfling explorers does not worry

about encountering ogres

in a network of three-foot-wide tunnels!

The relationship between

an area’s size and its potential for

cave-ins is also significant.

Some of the largest underground

caverns have ceilings that

soar hundreds of feet above the floor

and stretch as much as a

mile from side to side. Unless a cavern

of this size is magically

or physically supported, intelligent creatures

tend to avoid it when seeking

living quarters. Even a minor

earthquake, tremor, or landslide

could create a catastrophe of

colossal proportions by

caving in a section of the ceiling.

The races of the drow, duergar,

and derro do prefer large

underground areas for their

communities, but are careful to prevent

such disasters. Support

columns are the most common precaution,

but various permanenced

magical spells also serve to

prevent cave-ins.

Creatures such as the jermalaine

and pech choose small, constricted

tunnel networks as living

quarters. The small size of

these creatures is their

greatest defense in such locations. Other

underground creatures are

adaptable to many different types of

lairs, and can be encountered

in both small and large areas.

An important facet of underground

geography is the origin of

the spaces between rocks.

Caverns,

lava caves, and other naturally

eroded or developed places

vary widely size and shape.

Such locations are earmarked

by irregular walls, ceilings, and

floors. In fact, these surfaces

may be so rough, steep, or constricted

that travel on foot is virtually

impossible.

Areas that have been constructed

by intelligent races, on the

other hand, show evidence

of the builders’ craftsmanship. The

lairs of the duergar and

svirfneblin are the most smoothly carved

regions of the underworld.

Often, a large central cavern is developed

into a virtual domed city,

with individual residences excavated

into the walls of the cavern.

These skilled miners are

capable of digging a perfectly

straight tunnel many miles long, or

of creating ornate stonework

decorations.

Other races, such as the

drow and kuo-toa, have a limited ability

to excavate stone, but do

so if necessary. These creatures

much prefer to discover

a fine duergar lair, overcome the gray

dwarves’ defenses, and claim

it for their own. Races such as the

mind flayers and myconids

show no interest or ability in excavation,

and live in natural caverns

or abandoned dungeons.

The difficulty with which

creatures can journey from an underground

region to the surface tells

a great deal about the dark

region’s characteristics.

Fresh

air is much more plentiful in those

areas with some direct connection

to the surface. Of course, air

can flow through shafts

and tunnels that do not allow creatures

easy access (the miles-deep

shafts of the arctic ventilation

tunnels

present a good example of

this).

In general, areas that allow

easy access to the surface world

are populated by creatures

that occasionally leave the underworld

to raid or trade with surface

residents. Orcs, goblins, and

kobolds are good examples

of these races. Most of the cultures

of the Underdark, however,

prefer to dwell so deeply that they do

not have to worry about

the outside world. As these creatures do

not like to venture onto

the surface, likewise they do not welcome

intrusion from creatures

living above.

THEORIES

ON THE NATURE OF THE UNDERDARK

| The Hollow Earth Theory | The Swiss Cheese Theory | The Isolated Pockets Theory | The Partial Connection Theory | The Underground Environment: DM's Section |

Because only a few courageous explorers

have ventured into

the realms

of the underworld, and even fewer have returned

to

tell their tale, there are many unanswered

questions about the

exact nature of the world beneath the

earth.

Each of the following theories has been

proposed by adventurers

or sages

who have studied the history and nature of the dark

regions, and each theory has its own merits.

They are presented

for the DM’s use, and can provide insight

into world design. As to

which (if any) of them are correct, the

DM must decide which is

most consistent with his overall plans

for his campaign world.

These theories may not be common knowledge

among the citizens

of your campaign world, although you may

allow this if you

wish. It is more likely that each theory-

is regarded much as an

advanced scientific hypothesis is today-that

is, the information

is not regarded as secret by the sages,

but it is not of broad

enough interest to become a popular topic

of conversation

among the populace. If player characters

wish to find out about

some of these theories, they should seek

out knowledgeable

NPCs, and perform whatever role-playing

tasks are necessary to

gain the information.

This hypothesis holds that the earth’s

surface is a mere crust

over a vast open space, and that a wide

variety of life forms pursue

their existence almost completely isolated

from the surface

world. No adventurer is known to have

visited this inner earth,

and all reports of it originate from the

deepest of the underground

cultures.

Descriptions of the exact nature of the

hollow earth vary. Some

stories maintain that a vast atmosphere

exists beneath the crust

of the outer earth, and that a small version

of our own world rests

in the middle of this atmosphere. Obviously,

only creatures that

can fly || levitate

for long periods of time could possibly travel

from one world to the other. The inner

earth is presumably

cloaked in utter darkness, although rumors

tell of savage bouts of

volcanic activity that often light up

great tracts of it.

Other versions of this theory hold that

columns of fiery lava fall

from the outer earth and create a rain

of fire onto the inner earth’s

surface. The temperature there is reportedly

very high, and the

world hosts only those creatures that

have developed a considerable

liking for, or resistance to, fire.

Another hollow earth theory holds that

the entire center of the

earth is hollow, and that the outer earth

forms a thin shell around

this emptiness. Creatures reportedly live

on the inside of the shell

and look up to the center of the earth.

This theory is considered

one of the more far-fetched explanations

of life underground. A

variation of this explanation embraces

the same overall structure,

with an air-filled center, but denies

that creatures can walk

upside down on the inner surface of the

shell. Instead, the center

of the earth is home only to flying and

levitating creatures, and is

in fact a prime point of connection between

the Plane of Air and

our plane.

According to this theory, the world is

fundamentally solid with

no massive hollow space at its core, but

enough caves, caverns,

and artificial passageways exist to allow

an individual to travel

anywhere under the world.

The argument most commonly used in support

of this theory is

the widespread occurrence of many of the

common underground

races, such as goblins,

hobgoblins, and orcs. These creatures

can be encountered in most lands on the

surface. Since none of

them like to live (or presumably travel)

overland, it is argued that

their wanderings must have occurred through

a vast network of

tunnels underneath the surface.

The exact nature and origin of these tunnels

is left to speculation

by the proponents of this theory. It is

known that many characteristics

of goblins inhabiting the dungeons of

one land are

mirrored by goblins inhabiting the dungeons

of a land thousands

of miles away. This alone does not prove

the theory, since it can

be argued that the goblins might have

migrated overland, or that

their common traits were delivered to

both races by the same

source-an evil deity, for example.

Many adventurers have embarked upon missions

to prove this

theory true. Most of them have failed

to return, but those who

have emerged again report only failure.

All of the expeditions that

survived began by following a promising

route, only to find that it

dead-ended, circled back upon itself,

or led to the surface near

the starting point.

If there are indeed connections between

most of the realms of

the Underdark, this fact has not been

exploited by its denizens. It

could be that the passages are too small

to be used by great numbers

of individuals, that the distances between

the habitable

regions are too great, or simply that

strife among the denizens

has prevented large-scale movements from

one area to another.

This explanation is the least imaginative

of the theories, but fits

most closely with present observations

of the underground

regions. Although areas of vast realms

and highly developed cultures

have been discovered beneath the surface

of many lands,

the Isolated Pockets theory claims that

each of these underground

regions is an area unto itself, with no

subterranean connections

to any other underground regions.

The small bits of contrary evidence, such

as cultural similarities

between widely separated underground populations,

are

explained as either the results of migration

over the surface, or as

the influence of some deity not bounded

by the constraints of

geography. The overland migration of creatures

that hate sunlight

could have been forced. For example, a

migrating group of

humans may have taken goblins as slaves

and forced them to live

above ground for many generations. Perhaps

some of these goblins

escaped and sought refuge in underground

dungeons and

caverns. These goblins would have many

of the same cultural

traditions as their ancestors.

This theory is common among the most knowledgeable

students

of the underworld, but whether for any

intrinsic merit or

simply because it presents the best compromise

is open to speculation.

The theory maintains that there are indeed

connections

between all or most of the underground

regions, but stops short

of the Swiss Cheese theory’s

easy accessibility. The Partial Connection

theory holds that the connections between

widely separated

regions of the underworld are treach’erous

and often

impassable routes.

Fire, in the forms of volcanic activity,

lava, steam, etc., is commonly

suggested as a block to these passages.

Only creatures

with powerful resistance to fire could

be expected to traverse

these barriers. Water is the other commonly

mentioned obstacle

that makes travel through connecting passages

difficult or

impossible. Regions of the underground

that lie beneath the

deepest seas and oceans are unlikely to

be filled with breatheable

air, thus closing off many passageways.

The Partial Connection theory allows for

limited traverse

among the separate regions of the underground,

but only by

creatures capable of dealing with the

fierce obstacles lying in

their path. Alternatively, creatures could

have made a migratory

underground journey through a traversable

region in the distant

past, and that region could later have

been filled with water or

split by the fiery activities of volcanic

rock.