| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon 37 | - | Best of Dragon vol. II | - | Dragon |

***

Elric looked

at the pit. It was ragged and deep and the

earth in it seemed freshly turned as if it

had been but lately

dug.

“What must we wait for, Friend Corum?”

“For the Tower,” said Prince Corum. “I would

guess that

this is where it appears when it is in this

plane. ”

“And when will it appear?”

“At no particular time. We must wait. And

then, as soon as

we see it, we must rush it and attempt to

enter before it

vanishes again, moving on to the next plane.

”

—Michael Moorcock,

The Vanishing Tower.

***

The plane-shifting Vanishing

Tower of Moorcock’s Eternal Champion

series is only one of the

many fascinating means of travelling

between worlds found in

SF and fantasy literature. These “gates” (as

they are most often called)

are ideal for use in AD&D campaigns,

serving as means of moving

between the various Known Planes of

Existence.

Besides providing a means

of taking players into new areas or

settings (often regardless

of their wishes), gates have the added advantage

of allowing the DM to introduce

NPCs not otherwise consistent

with his or her world, by

providing a plausible way of getting them there.

Thus, characters from other

D&D

campaigns or famed in fantastic

literature (such as those

detailed in the series Giants In The Earth in

The

Dragon), or even

the occasional modern-day GI or superhero comicbook

character (say, one of the

Marvel X-Men) can take their bows.

Such characters (used with

extreme moderation!) can provide both

comic relief and interesting

player tests. A Prince of Amber or Chaos

from Roger Zelazny’s Amber

series, for example, could hellride an

unwilling player character

to a new plane and leave him there with little

chance of returning, as

Corwin did to Ganelon. Handle the prince as a

high-level psionic and the

“hellride” as the discipline probability travel.

Gates also provide a means

of shifting characters into a new, prepared

setting when the DM is changing

campaigns— i.e. from D&D to

AD&D,

or when one campaign has gotten out of hand and a fresh start is

desired, without placing

long-played characters into limbo forever. To

cut down on artifacts, et

cetera, the DM merely has them fail to work in

the new plane (referring

to Zelazny again, consider that the only explosive

that worked in Amber was

not gunpowder, but jeweller’s rouge).

Gates can also be used to

combine the campaigns of various DMs,

either by direct gate link,

or by providing a “common ground”; an area,

like Michael Moorcock’s

Tanelorn, which exists in all planes. And “since

Tanelorn exists in all planes

at all times it is easier for a man who dwells

there to pass between the

planes, discover the particular one he

seeks.” 1

An obvious choice for such a city would be a commercial

module or playing aid, such

as Judges Guild’s City-State of the Invincible

Overlord.

Various game systems (D&D,

MA, GW, Traveller and Boot

Hill, to

name a few) could be combined

(refer to the DMG and Jim

Ward’s

article

in TD -18 for the details of meshing rules and statistics) by gates

linking one game setting

(i.e. The Old West) to another (Camelot—why

not? Well, I’ll wait until

the Knights of the Round Table—and

Merlin—

appear in Giants

In The Earth; hint, hint).

The idea could also be adapted

to Traveller or other SF games,

operating in the manner

of Larry Niven’s matter transmission booths or

James H. Schmitz’s subspace

portals.2 Gates have an advantage over

the Amulet of the Planes,

which can force the DM to create, in depth,

any one of 21 to 24 planes

at the roll of a die. The problems this or

similar means of transport

(such as cursed scrolls or ancient grimoires—

cf. Codex

of the Infinite Planes) can produce are obvious (for an

example, see the introduction

to Gary Gygax’s Faceless Men And

Clockwork

Monsters in TD -17). Foreknowledge (and preparation) of

the players’ destination

avoids frantic dice-rolling a step ahead of the

exploring party (“ahh .

. . you see—um . . . a range of mountains in

the distance, and—ahh .

. . a—a band of orcs twenty feet from you

there are—ahh, fifteen of

them”; frantic rolling of hit points, etc., rapid

onset of nervous breakdown

on the poor DM’s part, not to mention the

players’). A Cubic Gate

or Well of Many Worlds is much better, but

often the DM does not wish

the players to control such items.

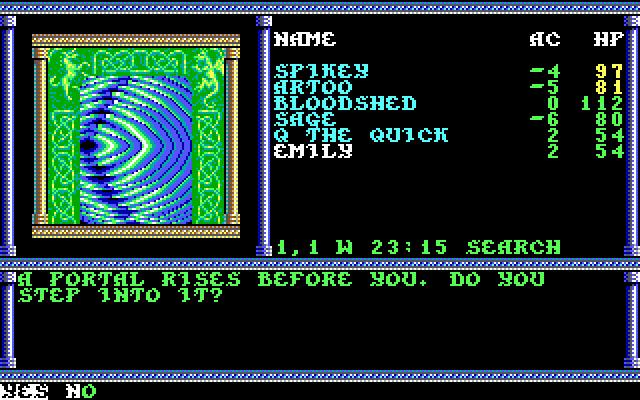

In its most common form,

the Gate is merely a space between two

standing stones. It may

be of three basic types: those which operate

constantly; those which

must be triggered by the use of a spell, talisman,

mechanical process, or word;

and those which operate periodically

(often in accordance with

stellar configurations, phases of the moon, or

solstices—such as Midsummer

Night—and equinoxes) regardless of

the presence or absence

of travellers. Typically, gates are both ancient

(locations and working almost

forgotten, or distorted by legend) and

well-nigh indestructible.

If they are destroyed, it is usually with an

explosion of awesome intensity.

Occasionally they are clearly the work

of superior (usually lost)

technology, and may have safeguards and

traps built into the controls.

DMs will find much of interest

and usefulness in fantasy and science

fiction works, and this

is as true for gates as it is for monsters or magic.

Some contain concepts ideal

for use by the DM. The Vanishing Tower is

perhaps the most spectacular

of these. It is a small stone castle, sections

of which appear shadowy

and vague. Lights play about its battlements.

It flickers from one plane

to another, spending only minutes or at the

most a few hours at any

location. There should be a warning flicker just

before it shifts (the DM

should count to ten, quickly, before shifting the

tower). The shift should

be more or less instantaneous and under the

directional control of no

person or entity (this will prevent players from

making it a cheap means

of all-powerful transportation, or worse, a

well-nigh unassailable fortress

which can shift away to escape danger in

any one plane). The only

exception to this lack of player control is the

provision (by means of a

Limited (or Full) Wish spell) for forcing the

tower away from the plane

of the spell caster. The spell caster should

have no knowledge of, nor

control over, its new destination when

driven away. The DM, however,

should know (and resist the temptation

to change) the tower’s destinations

and the occasions on which it shifts.

When using either the Tower

or the Ship (see below) a chart should be

drawn up showing the circuit

of planes travelled through. Dice can

determine the length of

time spent in each plane.

In Moorcock’s novels, the

“ordinary laws of sorcery”3 do not work

within the tower due to

the rapidity of its shifting and the varying

effectiveness of magic from

plane to plane, but individual DMs must

make their own decisions.

It is suggested that psionics and the following

spells not work within the

tower, or through its walls from inside or out:

Chariot of Sustarre, Contact

Other Plane, Control Weather (and similar

spells), Dimension Door,

Drawmij’s Instant Summons, Gate, Locate

Object, Passwall, Plane

Shift, Stone Tell, Teleport, Wizard Eye (and

related ‘spy’ spells), Word

of Recall. It is a matter of choice whether a

Magic-User within the tower

should be permitted to recall a Leomund’s

Tiny Chest.

The tower generally enters

any given plane in relatively the same

spot (see opening quotation)

each time. Note that this is by no means

certain, and the irregularity

of its presence (coupled with the length of

absence) will in most planes

deny precise knowledge (and perhaps

guarding) of its point of

entry. Often only old, distorted legends and

crumbling, forgotten records

will hint at where it may be found when it

does appear.

Often the tower will be inhabited

by creatures venturing into it from

the various planes it visits

(for example, if the Tower has visited any of

the Nine Hells at all recently,

it will certainly have been garrisoned; one

might assume the archdevils

have given standing orders regarding this).

Monster possibilities are

obvious.

In the original, a dwarf

named Voilodon Ghagnasdiak inhabited the

tower (after discovering

its plane-shifting properties the hard way). Too

fearful to leave, but very

lonely, he captured those who entered the

tower and forced them to

be his companions until he grew tired of them

and killed them. He had

a number of winged, monstrous servants

(seemingly equivalent to

gargoyles) who could be harmed only by the

scythes they bore. Like

the monster in Wormy, TD -18 and 19, these

were initially imprisoned

within balls which the dwarf would throw at

those menacing him. In the

depths of the tower was a vault filled with the

treasure of all those who

had ventured into the tower and fallen prey to

Ghagnasdiak. Such a hoard

would include many strange artifacts

(perhaps Gamma World weapons

and armor) and much magical treasure.

In the original novel, one

such artifact was the Runestaff, which

apparently has the power

to halt the tower’s shifting (although it was

never so used). It can itself

shift its holder and anyone touching him or

her to any plane desired—whereupon

it will vanish.

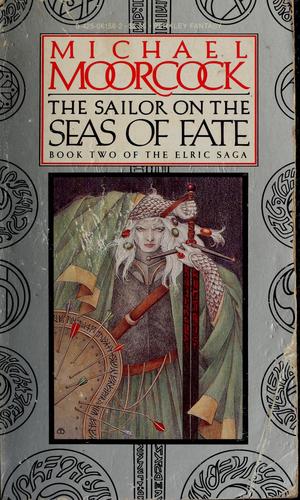

The Ship That Sails

The Seas of Fate is also of Moorcock’s invention.

It is a ship of dark and

strange design, with a curving, warlike prow,

ornately carved rails and

figurehead, elevated decks fore and aft. With a

tireless crew of two, a

blind captain and his twin the steersman, it sails

through the planes on an

apparently foreordained route. As the captain

tells Elric, “We’ll sight

land shortly. If you would disembark and seek

your own world, I should

advise you do so now. This is the closest we

shall ever come again to

your plane.”4 Always shrouded in mist, the

Dark Ship seems to spend

much of its time in the astral plane, en route

from a sea in one plane

to another sea in the next, rather than shifting

instantaneously as the Tower

does.

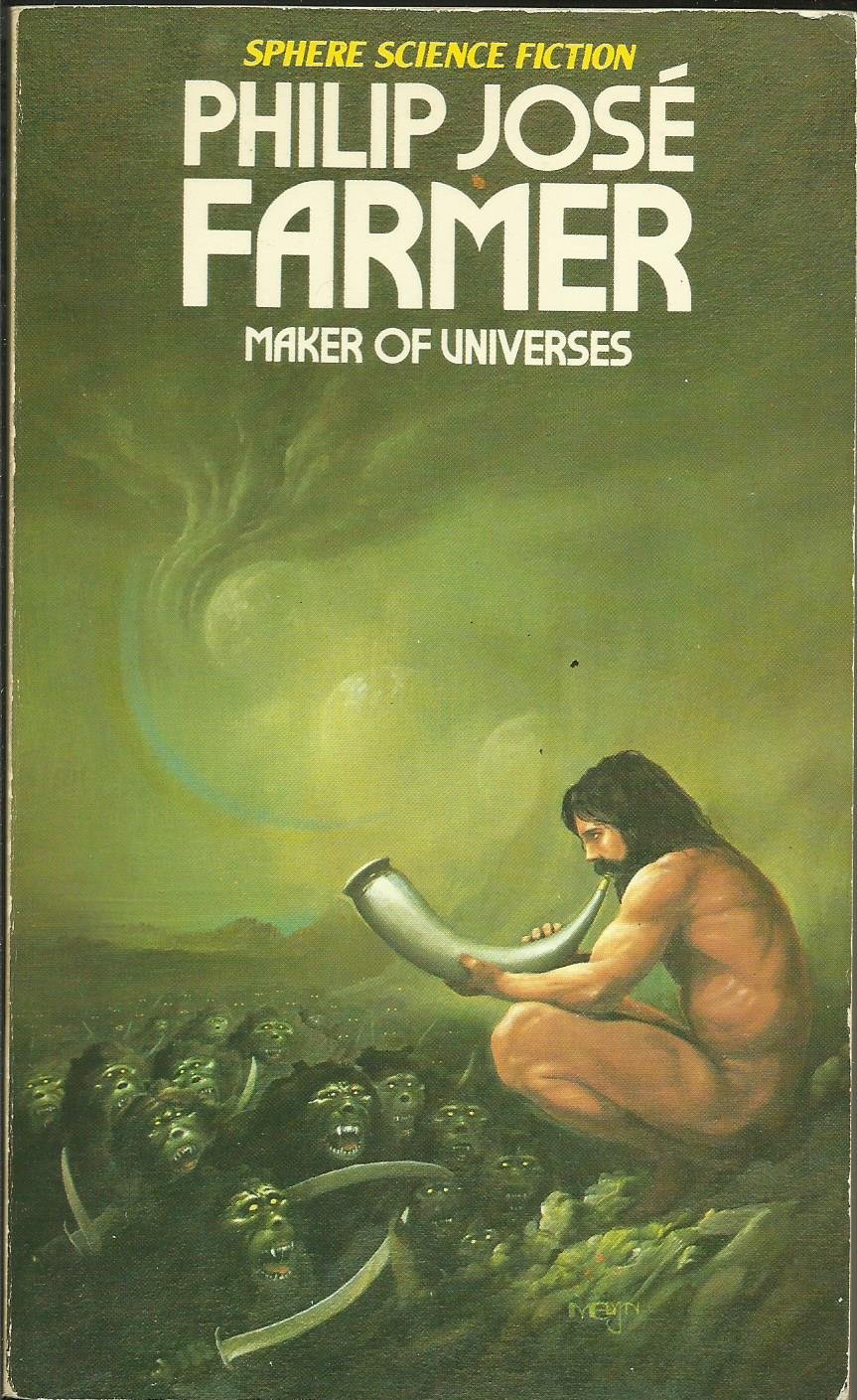

The magnum opus of gate systems

is Philip Jose Farmer’s fivevolume

World of Tiers

series.5 Gates therein are of many types, most

commonly doorframes or hoops,

or matching crescents (which must be

joined to activate the gate)

or seemingly indestructible metal. Passage

through them is so instantaneous

that one may step through an open

doorway and be gated into

another room (identical to the one the door

physically opens into) without

realizing it. Air passes through the gates

automatically, to prevent

the ‘pop’ of air rushing into a sudden vacuum

as someone vanishes. Gate

fields can cut anything, and are used (at

various points in the series)

to neatly carve up huge rocks, trees, and

enemies of various sorts.

Gates may be portable, or

partly so (one crescent set into a floor or

boulder, often concealed,

and the other loose, usually hidden elsewhere).

Gates may be set to allow

passage of masses up to a certain

maximum; thus, men or large

animals can be kept out. Gates are usually

found in pairs (that is,

entry and exit, or vice versa) which share the same

“resonant frequency.” Such

a frequency may be changed by the use of

sophisticated machinery

to turn the gates off (perhaps cutting someone

in half!) or align them

with other gates, changing the destination any

given gate leads to. Gates

may be set for one-time operation, random

resonance changes, or activation

only by code words. They may also

“flipflop”; that is, automatically

change their resonance after being

activated, so that the next

time the gate is used it will lead somewhere

else.

Gates may also be traps (and

in Farmer’s books, usually are). They

may be set to kill those

trying to use them or entering them in the wrong

direction or manner,6

or lead to “inescapable” prison cells (see Mark S.

Day’s

article in TD -23 or Farmer’s novels), undesirable planes, or

to

almost certain death (i.e.

into midair, a mile from the ground). The hero

of the series, Kickaha the

Trickster (who’d make a great GITE—

Lawrence Schick and Tom

Moldvay please note!), escaped from one

such cell by crouching atop

an empty food platter and being gated to the

kitchen. (Gates are often—especially

in cells—used as dumbwaiters,

with a matching pair of

gates in the kitchen and set into the top of the

dining table.)

The usual way in which gates

kill is an electrical discharge powerful

enough to crisp flesh, but

Farmer also has one that shoots burning oil at

anyone standing in front

of it when it is first activated (thus, anyone in

the know would stand to

the side, toss a stone through the gate, and wait

for the fireworks to die

down).

Another underhanded trick,

ideal for

scattering parties, is a

second, delayed gate set off by passing through

the first (so as to catch

the third or fourth person in the marching order).

The most spectacular trap

is a circuit or series of gates, each activated

by the preceding one, so

that people entering any gate in the

circuit are trapped, blinking

in rapid succession from one location to

another. They are vulnerable

to attacks in the few seconds they are in

each location (usually by

missiles), and can leave the circuit only by

leaping out of a gate during

that very brief time. If they misjudge the

timing, they are bisected

or otherwise mangled as part of them is gated

on to the next location.

A base chance of leaping out successfully of

60% is suggested, plus 5%

for every point of Dexterity over 15, and

minus 5% for every point

under 12. For every 10 HP that the character

may have currently lost

(i.e. wounds), also subtract 5% from the chance

of success. If a character

is caught by the gate shift, he or she must save

vs. paralyzation or be cut

in half (instant death). If the save is made, the

gate is considered to have

severed a limb or something of the sort, and

such a wound will have to

be cauterized to prevent the character from

bleeding to death. The character

will take 2d12 damage and must save

vs. System Shock, or die.

If the trapped person has a friend at one of the

locations visited by the

circuit, the friend can stop the circuit by jamming

the empty gate so full of

matter that the maximum mass it can shift is

reached and it stops working,

shutting down the circuit. Of course, the

trapped person will be freed

elsewhere in the circuit, which may be

several planes away.

An artifact, The Horn of

Shambarinen, has the power of opening

gates between planes whenever

its seven notes are sounded in the

proper sequence at a resonant

point in any plane (the DM must determine

which plane the resonant

point is adjacent to, and thus where

the gate will lead). It

can also match the resonance of any existing gate

and operate it (without

the usual key, device, or missing crescent). Gates

glow if the Horn is played

close to them (say, within 60’) and the

horn-blower can see through

the gate into wherever it leads. The Horn

resembles a silver Horn

of Valhalla, with seven buttons set in a line along

its top, and the mouth of

the horn filled with a silvery web. It is

constructed of an unknown

and seemingly indestructible metal, and

bears the hieroglyph of

Shambarinen on its underside.

A more recent series of books,

C.J. Cheryh’s Morgaine trilogy,7

illustrates the attitude

of medieval-level cultures to gates in their midst.

An early and excellent use

of gates is found in C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of

Narnia,8

which incorporates a fascinating campaign setting: The Wood

Between The Worlds. This

is an ancient woods into which almost all

gates open, and as a result

is peopled with many strange and wonderful

creatures. A tavern in such

a place would abound with fascinating and

powerful NPCs. And that

painting over the bar, if one stares at it for a

moment, can be stepped through,

into . . . Well, have fun.

Notes

1. Michael

Moorcock, The Vanishing Tower, p. 152 (DAW paperback).

2. See Schmitz’s

The

Lion Game— a DAW paperback—for a huge dungeon of

rooms connected by portals,

with many traps and ‘lost’ sections.

4. Michael

Moorcock, The Sailor On The Seas Of Fate, p. 58 (DAW

paperback).

5. The books,

available in Ace paperbacks, are (in chronological order): The

Maker Of Universes;

The

Gates of Creation; A Private Cosmos; Behind

The

Walls Of Terra;

and The Lavalite World. Essential references, all.

6. One such

‘killer gate’ was a doorframe revolving rapidly in midair. Identification

of the ‘safe side’ was of

course very difficult. Another might be a

doorframe, only the upper

half of which is a gate, so that anyone stepping

through the gate in a normal

manner (rather than leaping) will be cut in half as

only their upper body gates

away.

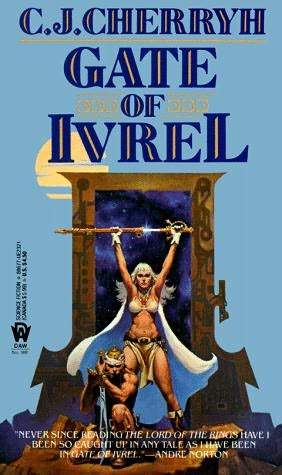

7. Gate of Ivrel; Well of Shiuan; Fires of Azeroth (DAW paperbacks).

8. In chronological

order: The Magician’s Nephew; The Lion, The Witch &

The

Wardrobe;

Prince

Caspian; The Voyage of the Dawn Treader;

The

Silver

Chair; The

Horse and His Boy; and The Last Battle, available

in Puffin

paperbacks in Canada and

Macmillan paperbacks in the States. The first five

bristle with material of

interest to D&D players. The Wood Between The

Worlds appears in Chapter

3 of The Magician’s Nephew.

Alan, either works with

me.

As another fan ot Farmer's

"Created UIniverses" series, I used gates generally, although Iggwilv

is capable of transpirting herself to various known locations without such

aid.

Cheers,

Gary