A second

volley:

Another shot at firearms,

this time smaller ones

by Ed Greenwood

A second

volley:

Another shot at firearms,

this time smaller ones

by Ed Greenwood

| Dragon 70 | - | Best of Dragon, Vol. V | - | Dragon |

Early firearms

| Gun name | Typical

caliber |

Cost (gp) | Avg.

wt. (lbs.) |

Avg.

overall length |

Range

(in game) S |

M | L | Damage

S-M |

L | Rate of fire

(one man) |

Rate of fire

(gunner and loader) |

| Arquebus | Widely

variable |

500 | 25 | 3'4" + rest (up to 4' 6") | 3 | 7 | 12 | 1-10 | 1-6 | 1/3 | 3/2 |

| Caviler (matchlock musket) | Variable | 450 | 11 | 4'6" | 4 | 8 | 14 | 2-9 | 1-8 | 1/2 | 1 |

| Dragon ("Dagg" or "horse pistol") (wheel-lock pistol) | .50 | 600 | 4.5 | 1'4" | 1 | 2.5 | 4 | 1-6 | 1-3 | 1 | 1 |

| Flintlock pistol | .60 | 550 | 2 | 1'2" | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1-6 | 1-4 | 1 | 1 |

| Early flintlock musket | .70 | 800 | 10 | 5'6" | 10 | 20 | 30 | 3-12 | 1-10 | 1 | 1 |

| Blunderbuss | Widely

variable |

500 | 8 | 2'4" | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1-10 | 1-10 | 1/2 | 1/2 |

Note: The prices shown on the table are those in an area where weapons

are plentiful, and ammunition, repairs or

manufacture of same is nearby. Prices should be doubled, tripled, or

even increased by a factor of ten where weapons

are rare and/or are objects of prestige or power.

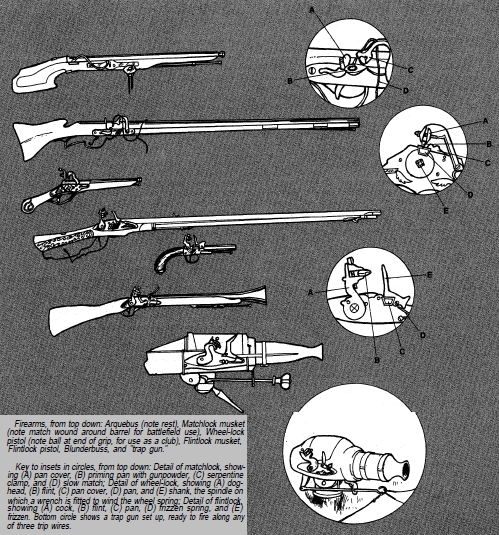

Since the appearance of “Firearms” in

DRAGON™ issue #60, several readers

have requested a similar treatment of the

small arms which developed from the

handgun. Accordingly, here is a brief

look at the arquebus and its successors.

The historical development and battlefield

use of such weapons are familiar to

many gamers and readily available in

library books to most others, so military

history pertaining strictly to our “real

world” has been omitted.

In some campaigns, a firearm

makes for a deadly weapon.

It is again recommended here that in

an AD&D campaign, gunpowder should

be considered undiscovered or inert, so

that firearms cannot be used in the

“standard” fantasy setting. Experimental

and enjoyable play involving firearms is

best safely confined to parallel “worlds”

(alternate PMPs which can be reached

only by the use of magical items, spells, or gates).

A campaign can be quickly unbalanced

by firearms that are too accurate, or easy

to use, or numerous. I once visited a

campaign in which a cache of weaponry

culled from the GAMMA WORLD™ game

was walled up in the first level of a dungeon.

Excavations into a suspiciously

circumvented area on our dungeon maps

won us an arsenal of powerful explosives

and lasers — and deadly boredom. Frying

our first dragon was quite exciting,

and the second was a workmanlike but

still enjoyable job. But the third was routine,

and the rest (it was a large dungeon)

were boring. Once we’d run out of

dragons, we sallied forth from the looted

dungeon and barbecued a nearby wandering

army of orcs. Play soon ended in

that campaign; the party members became

absolute rulers of an almost featureless

landscape, having destroyed

everything they didn’t fancy the looks of.

On the other hand, the occasional

“hurler of thunderbolts,” held by an individual

NPC and jealously guarded for

use only in dire emergencies, is an acceptable

and useful “spice” for an AD&D

campaign in need of same. Longtime

readers of DRAGON Magazine will recall

(from “Faceless Men And Clockwork

Monsters,” issue #17) that an adventurer

recognized a firearm because he had

once seen a mage in Greyhawk with

“such a wand.” Such rarity and misunderstanding

(i.e., the assignment of magical

status) of firearms appears the best

way to handle such weapons in an AD&D

game.

Before embarking on a brief tour of the

small arms developed from the handgun,

it is well to bear in mind that during these

times no large munitions factories or

production standards existed (and unless

all firearms in the AD&D setting

come from one source, this is likely to

hold true in play as well). As a result,

almost every weapon is unique, having

individual characteristics due to varying

barrel dimensions and materials, amount

and mixture of gunpowder used, and differences

in the shot employed. Small

arms were in use for a very long time

before King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

introduced a fixed cartridge of bullet

and powder. Until then, everyone measured

their own powder charges on the

battlefield. The timid did little damage to

the enemy; the reckless blew themselves

up. The statistics shown on the tables

given in this article should therefore be

treated as a “typical” base, to be modified

freely to fit the situation at hand.

It is also necessary to keep in mind the

accoutrements of a gunner: oil, to keep

the weapon in working order and free of

rust; a watertight carrying container for

gunpowder (such as the powder horn of

the American frontier); rags, to clean

and wad with; shot, usually large metal

balls for piercing armor and stopping

men, and handfuls of tiny metal pellets

for shooting fowl and vermin; and a rod

or rods (often carried slid down one side

of a boot) for cleaning out the barrel and

ramming the shot home. Details of these

vary from weapon to weapon; a DM

should keep track of such heavy and

awkward gear, and try to keep the use of

guns a fussy and not too rapid business

— in a street fight one should grab for a

blade, rather than whipping out a pistol

or musket and clearing the field — because

one would risk a fatal misfire, and

in any case would have to coolly stand

for one round loading the firearm between

each and every shot. A more complete

list of a gunner’s equipment is provided

later on for those who wish to

consider encumbrance in detail.

The primitive handgun was a small

cannon on a stock. It was fired by means

of a red-hot wire put through a touchhole.

Later, a slow-burning match (usually

a cord that had been soaked in nitre

and diluted alcohol and then dried) replaced

the wire. The flame of the “slow

match” was more likely to ignite the

gunpowder, and the implement was both

easier and safer to use: A wire had to be

heated in a non-portable fire laid on the

ground, which could be perilous with

gunpowder nearby, whereas a slow

match could be lit with flint and steel at a

safe distance, and carried to a more

mobile gunner.

Later, the matchlock replaced the

hand-held match; at the pull of the trigger,

the lit match was dipped in a pan of

gunpowder by the S-shaped clamp (or

“serpentine”) which held it. Firing became

more rapid and more accurate — a

gunner could now look at his target

when preparing to fire, rather than concentrating

on the touchhole.

The matchlock was faster than the

handgun, but not fast by any other standards.

Firing it required ninety-six separate

actions — such as measuring the

powder and pouring it down the muzzle;

dropping in the lead ball and then a wad

of rag; uncovering the priming pan, filling

it with powder, and closing the pan

again; adjusting the position of the match

in the serpentine, and lighting the match;

and then opening the pan again, aiming,

and pulling the trigger. As author Richard

Armour puts it, “the gunner hoped his

target would hold still while all this was

going on.” (This last statement is from

Armour’s hilarious book, It All Started

With Stones and Clubs (Being a Short

History of War and Weaponry from Earliest

Times to the Present, Noting the

Gratifying Progress Made by Man Since

His First Crude, Small-scale Efforts to

Do Away’ with Those Who Disagreed

With Him); published by McGraw-Hill,

New York, 1967.)

The matchlock had other disadvantages,

too: a premature ignition of the

potentially dangerous open pan of powder,

too much powder, or simply an

uneven distribution of powder in the pan

(ever try carefully levelling a spoonful of

powder in the midst of a battle?) could

cause an explosion at the expense of the

gunner and not the target — the source

of the expression “flash in the pan.”

The barrel of a matchlock was fouled

by gunpowder with each shot, and in a

long engagement its accuracy declined

as the recoil caused by the fouling grew

wilder, leaving a gunner’s shoulder numb

and bruised. A curved stock was soon

devised to reduce the recoil impact.

There was also the problem of shooting

in the rain; water could easily put the

match out. Surprise was impossible

because of the smell, glow, and noise of

the matches; and it was not unheard of

for one gunner to set off his own or a

comrade’s ammunition. Although names

have been applied rather loosely over

the years to all sorts of weapons, I have

confined “arquebus” to the earlier versions

of the handgun, and “caliver” to

the lightened matchlock musket.

The musket was an upgunned arquebus,

and consequently was so heavy that

it had to be supported on a crutch or a

rest. It was almost a hundred years

before the weapon was lightened enough

to dispense with these supports. Although

the musket fired a heavier shot, it also

jumped in the rest when fired, resulting

in lower accuracy. But its bullets could

pierce the best armor that could be worn

by a foot soldier. (As this became known,

soldiers in full armor all but disappeared

from battlefields, and subsequent small

arms could be made smaller; the musket

no longer needed its rest.) Musketeers

still had to be protected by non-shooters

while loading their pieces, but almost

overnight firearms became the dominant

force in warfare. Infantry who did not

employ muskets were armed with pikes,

so that a musketeer could undertake the

slow, clumsy process of reloading safely

within the long reach of defending pikemen.

When pikeheads were attached to

muskets (upon the invention of the bayonet),

the pike disappeared.

Two “firelock” mechanisms, the wheellock

and the flintlock, were developed to

solve the problems of the slow match.

Both could be loaded and primed at leisure,

to be fired at a moment’s notice.

But both were more expensive than the

matchlock, more likely to go awry and

misfire or need repairs, and could be

fired fewer times before needing cleaning.

As a result, they took a while to catch

on.

The wheel-lock was never widely used

by infantry. Rather than a match, it employed

a saw-edged wheel wound up

with a spring and a piece of iron pyrite

(or flint) held against it in a doghead vise.

When the trigger was pressed, the wheel

(like a cigarette lighter) would spin,

shooting a shower of sparks into the

priming powder in its enclosed pan. If

properly loaded with dry powder, adjusted

and wound, a wheel-lock firearm

would almost certainly fire when the

trigger was pulled, even in a rainstorm.

Cavalry could carry loaded pistols in

their holsters for hours or even days.

Although the wheel-lock was complicated

and slow to load, this “at the ready”

feature revolutionized cavalry tactics.

Rather than using the shock of their

charges to strike and overrun infantry

(the reason for pikes), cavalry now performed

such dangerous maneuvers as

the “caracole,” lines of armored cavalrymen

carrying three pistols each formed

up in lines. Each line in succession rode

up to the enemy, fired, and swerved off to

reload and form up again in the rear. Not

only was this maneuver overly complicated,

but a cavalryman riding close

enough to shoot enemies could himself

be shot at, both by firearms and longbows.

Nevertheless, the addition of

wheel-lock pistols restored to cavalry

the effectiveness it had enjoyed before

pikes and muskets faced its every charge.

The flintlock was to become the standard

infantry weapon for more than two

hundred years (until the advent of the

percussion cap, which resulted in the

cartridge or “bullet” familiar to us now,

and a firing mechanism consisting of a

pin driven forcefully into the rear of the

cartridge by a pull of the trigger). The

flintlock resembles a tinderbox — a flint

strikes steel, and the sparks created fall

into the priming powder. The flint is held

in a “cock” or vise which (unlike the

wheel-lock, wherein the vise is stationary)

flies forward like the hammer of the

familiar Colt revolver to strike a steel arm

(the “frizzen”) when the trigger is pulled.

Although not as surefire as either the

matchlock or the wheel-lock, the flintlock

is cheaper and simpler, more durable,

and easier to repair in the field. If the

flint does not need adjusting, a flintlock

can be loaded slightly faster than a

matchlock — and it can be loaded in

advance and carried. ready to fire one

shot at a moment’s notice. The persistent

failing of the flintlock revealed over

centuries of use is that it too often misfires

(does not go off). At least, this failing

is preferable to one of the main

drawbacks of earlier firearms, which was

that they literally blew up in the gunner’s

face.

Firearms were of course continuously

modified and improved upon, but this

article will not follow on to rifled barrels

and the other innovations of the Napoleonic

era and later weaponry. Instead,

mention must be made of another development

of the same idea, which is basically

to increase the chance of striking a

target by firing a spray of shot rather

than a single bullet or ball. A blunderbuss

has a short, trumpet-flaring barrel

which is loaded with powder, wad, and a

handful of iron balls or whatever was

available. This was the chief advantage

of the blunderbuss: one traded muzzle

velocity (and thus penetrating power,

range, and accuracy) for the ability of

the weapon to take stones and other projectiles

that need not be carefully shaped

to a specific bore (barrel diameter).

Farmer Giles in J. R. R. Tolkien’s delightful

fantasy Farmer Giles of Ham used

“anything he could spare to stuff in” as

ammunition: old nails, bits of wire, pieces

of broken pot, bones and stones

“and other rubbish.” Giles fought off a

giant with his blunderbuss, even if firing

it did leave him flat on his back.

A blunderbuss barrel can be made of

brass, or a length of stove pipe; it is easy

to build and to repair. It can fire anything

small enough to easily fit in the barrel: a

pound of nails, say, or odds and ends of

lead castings or rusting ironmongery

(this last usually resulted in infected

wounds). A covered blunderbuss, known

as a “spring gun,” could be set up to

discourage poachers and other intruders;

it would be mounted on a swivel post

a foot or less off the ground and attached

to three or four long trip-wires leading

off in all directions. When someone disturbed

one of the wires, the strain would

act on a rod beneath the gun attached to

the hammer or cock of the flintlock, and

the gun would instantly swing around

and fire along the tripped wire.

Any gunner in an AD&D setting

must

carry the supplies of ammunition and

tools necessary to keep his or her temperamental

weapon in working order. In

practical terms, this generally consisted

of keeping one’s gunpowder dry and

cleaning the weapon after every use.

Taking a primitive firearm into battle is a

time-consuming job. It is also a skill to

use it effectively; every shot must count

when the firing rate is so low, and one

cannot snatch up a weapon and pick off

a target when it must be carefully loaded

with a precise amount of powder and the

right size of shot. (The use of too-large

shot will destroy the weapon and usually

also the gunner, whereas too-small shot

rolls along one side of the barrel, acquiring

a spin perpendicular to the line of

fire, and therefore an unpredictably

curved flight path.) It must also be aimed

with care: none of the guns described

above will work if not upright; the “snapshot”

of the western gunfighter or modern

commando is impossible to execute.

Necessary gear for a gunner consisted

of matches or flints, a large flask of

(coarse) gunpowder and a small “touchbox”

of fine priming powder. Often these

last were of wood, and carried slung on a

bandolier like the modern movie GI carries

grenades: when pulled, the top of

the flask remained behind, and the gunner

put a thumb over the top of the

touchbox (which contained just enough

powder for one firing) until he could

upend it into the priming pan. The

matchcord was carried wrapped around

one’s hat (inside the hat in wet weather),

and flints were usually carried in a belt

pouch, wrapped so as to keep them from

chipping and striking sparks from one

another if the holder had to run or

scramble about.

Bullets or shot were carried in belt

pouches, and when in action, a couple

for immediate use were often held in the

gunner’s mouth (much as a tailor holds

pins). All firearms also required ramrods

(most of which were carried in a slot provided

in the gunstock), scrapers, and

cleaning rags and curved metal extractors

(which resemble miniature golf

irons) for raking out bullets or shot. Making

bullets required lead and a brass

mold; often only one mold would produce

bullets of the right size for a particular

gun. Flint and steel, and dry kindling,

were required for lighting slow

matches and/or laying the fire necessary

to cast bullets. To use the early arquebus

practically in battle, a gunner needed a

helper to tend his fire, mix the ingredients

of gunpowder (at a safe distance

from the fire) and carry the weapon’s rest

(in battle, the gunner himself carried it

about by a loop of cord tied around his

wrist). Wheel-lock weapons also required

a “spanner” or key which wound up a

chain attached to the spring which spun

the wheel, usually carried tied to one’s

belt so that it would not be lost.

A gunner also carried a sword and a

dagger (which served also as eating

knife, flint scraper, and cleaning tool),

and in a pinch could use the pointed end

of the crutch-shaped rest for defense.

Most early pistols were made with huge

balls or knobs at the butt end of the grip,

so that when empty they could be used

as clubs — doing 1-3 points of damage,

1-4 if a mounted wielder is combating a

target on foot. A musket uses up to two

ounces of powder per firing; one pound

of lead made eight musket balls if they

fitted the barrel tightly, or ten if they

“rolled in.” Modern shotgun gauges developed

from this sizing of shot by the

number of bullets to the pound.

Firearms:

The first guns weren't

much fun

by Ed Greenwood

| Early guns | Gunsmiths and their equipment | Gunpowder | Guns | Firing guns |

| Naval use of gunpowder | - | Strategic importance of gunpowder | - | Equipment |

| Dragon 60 | - | Best of Dragon, Vol. V | - | Dragon |

Gunpowder — and the advent of ballistic

weapons — proved the beginning

of the end for the medieval warfare depicted

in the AD&D™ world.

Armor, bladed weapons, stone castles

— all were made obsolete by gunpowder

and firearms. Nothing withstood “the

great equalizer” that let men kill from a

safe distance without concern for personal

strength or valor.

So, the Dungeon Masters Guide for

good reason warns against the desire to

“have gunpowder muddying the waters

of your fantasy world.” (p.

113) Yet, introducing

gunpowder to a campaign

raises some fascinating possibilities. The

trick, of course, is limiting the use of firearms

to maintain game balance.

For example, DMs should not allow

alchemists and artisans to greatly

improve

the technology of firearms in their

world; gunnery should remain an art, not

a science. For a long time artillery was

rare, expensive and clumsy in battlefield

use— more a psychological than a physical

weapon. The use of gunpowder in a

fantasy world should reflect this; with

proper design, almost any early firearm

could be introduced into the AD&D

setting,

if the DM can devise a logical justification

for its presence. With this in

mind, what follows is historical information

on various firearms, with ideas for

translating them into play.

The first real gun was a large, bottleshaped

iron pot that fired an enormous

crossbow bolt when powder in its bottom

was ignited. Such weapons were

known as “Pots de Fer,” and were made

as early as 1327 in England,

In 1328, the French fleet that raided

Southhampton in the opening year of

the Hundred Years’ War was outfitted

with one “Pot de Fer,” 3 Ibs. of gunpowder,

and 2 boxes of 48 large bolts

with iron “feathers.” Although arrows

and bolts were soon replaced by bullets

of lead, iron, or stone, they were still being

fired from muskets as late as the time

of the Spanish Armada, and ribalds made

in England in 1346 are known to have

fired “quarrels.”

The guns the French used to defend

Cambrai the following year were bought

from artisans by weight, and averaged

only 25 Ibs. per gun.

The most popular gun of this period

was the “Ribald,” a series of small gun

barrels clamped together (looking somewhat

similar to the much later Gatling

gun or the Nebelwerfer). Their touch

holes were arranged so a single sweep of

the gunner’s match would set them all

off.

Ribalds were usually mounted on

wheeled carts, with a shield to protect

the gunner from arrows, These “carts of

war” were particularly useful when aimed

at breaches and doorways. However, the

balls fired by a ribald were far too small

to breach walls, and the weapon took a

long time to load or reload — each tube

had to be cleaned out, filled with a

charge of powder and a ball, wadded,

tamped down, and primed.

By the 1340s, 3-inch caliber guns were

used for sieges, and in at least one instance,

by the English at Crecy in 1346,

on the battlefield. These guns fired balls

of iron and stone and the three cannons

at Crecy sold the English on the use of

artillery.

Most of these early pieces were cast in

brass or copper rather than iron. In 1353

Edward III ordered four new guns cast of

copper from William of Aldgate, a London

brazier. The guns cost the equivalent

of about $150 each in today’s money.

These were probably small guns,

because large castings tended to have

flaws and airholes. This led to the guns’

distressing habit of blowing up when

touched off, killing the wrong people.

James II of Scotland was killed in 1460,

while besieging Roxburgh Castle, when

one of his big guns, a bombard made in

France and called “The Lion,” blew up

and a piece of shrapnel struck him in the

chest.

Despite the risks, large barrels were

effective in battering down castle walls.

These were wrought rather than cast.

White-hot iron bars were laid side-byside

around a wooden core and welded

together by the blows of the gunsmith’s

hammer. Iron rings or hoops were clamped

around the barrel to strengthen it.

As the arts of metallurgy and casting

improved, bronze cast guns replaced

hooped guns. By the end of the 15th century

hooped guns were rarely seen. Missiles

during this time were almost entirely

of stone; firing metal balls was simply

too expensive. Cannon-ball cutters were

skilled workers, paid as much per day as

a man-at-arms.

At the siege of Harcourt in 1449, a gun

produced by the Bureau brothers did

heavy damage — “the first shot thrown

pierced completely through the rampart

of the outer ward, which is a fine work

and equal in strength to the Keep.” In the

next year, the Bureau brothers’ guns

took sixty fortified areas. Many Surrendered

as soon as the big guns were in

position, for the defenders knew they

would simply be battered to pieces. It

was no longer necessary to starve someone

out of his castle — you could now

blow it down about his ears.

On the battlefield, however, supremacy

was much longer coming. Early guns

were emplaced on earthen mounds and

dug in, or upon wooden platforms. These

were not mobile, so if an enemy avoided

the ground the guns were aimed at, the

guns were useless. Mobile carriages were

introduced in the early fifteenth century

(such mounted cannon were known as

“snakes”) but the introduction of lightweight

horsedrawn gun carriages and

trunnions (the projections on a gun barrel

that act as pivots for elevation) came

later. Cannons had smooth bores for

centuries before successful rifling was

developed, and the maximum effective

(wall-piercing) range of a 14th century

smooth-bore cannon was 200 yards with

a 30-lb. missile.

DMs should not allow reliable handguns

or shoulder arms in their AD&D

worlds, although historically, one-man

firearms were in use as early as 1386.

The individual barrels that made up ribalds

were mounted separately on spearshafts

and given to men-at-arms. A soldier

put the spear shaft under his arm,

resting its butt on the ground behind

him, and fired the handgun by lighting a

“match” (a length of cord impregnated

with saltpeter and sulphur so it burned

slowly and evenly). These guns, which

fired high into the air and were difficult to

aim, were soon replaced by short-shafted

weapons that rested against the chest or

shoulder. These were very inaccurate,

but when firing in massed volleys could

be quite effective.

Such firearms were unpopular with

knights, for the lowliest peasant could

pierce armor with one. Professional

soldiers weren’t too happy, either. Shakespeare

captures their feelings when he

calls gunpowder “villainous saltpeter,”

and a Venetian mercenary army in 1439

massacred Bolognese handgun men for

using “this cruel and cowardly innovation,

gunpowder.”

Soon gunstocks had hooks that caught

on a parapet or barricade to absorb

some of the recoil. The development of

the matchlock gun allowed guns to rule

armor, and the medieval setting typical

of AD&D adventuring was largely

gone.

The matchlock gun became the musket,

wheel-lock guns were introduced, and

modern weaponry was in sight.

Gunsmiths and their equipment

Player characters should not be allowed

to obtain skill in gunsmithing, nor

in battlefield gunnery (save at great risk,

in emergency situations). Historically,

gunners were artisans, private individuals

who produced firearms for a fee and

often hired themselves out to work the

guns they made. The price of a gun or

guns always provided the buyer with the

weapon, any stands or carriages necessary

for its use, ammunition, gunpowder

(or at least its ingredients), and all the

necessary gunners’ equipment: drivells

(iron ramrods), tampions or tompions

(wads), matches, touches (for lighting

matches or powder through a touchhole;

a “touch” is basically a torch mounted on

a pole), and firing pans (metal pans filled

with hot coals, to light the touches so no

flint and tinder were used to avoid

sparks). Gunmakers provided bags of

hide to carry the gunpowder, and scales

and a mortar and pestle for mixing it.

They manufactured barrels of all sizes

with locks, to store gunpowder in a castle

or permanent gun emplacement, and

trays of wood or brass in which damp

powder could be dried over a fire or in

the sun. If their guns fired cast bullets

— of iron, brass, copper, or lead — the

gunners provided the molds for each

firearm.

A gunsmith, one can see, was both

highly skilled and versatile, and often

employed underlings to round stone balls,

work and cast the metal, and manhandle

guns in battle. DMs may wish to increase

the smith’s fee over that given for an

“engineer-artillerist”

in the DMG (p. 29-

30) on the grounds that men familiar with

these new and relatively mysterious

weapons are in great demand, and rare.

Two hundred gold pieces a month seems

about right (plus 10% of the cost of weapons

made, as mentioned in the DMG),

but remember that demand, supply, politics,

alignment, and character will affect

a gunsmith’s charge; a party should

find a gunsmith’s services quite dear — if

not outrageous.

A gunsmith is capable of all the tasks

of an armorer or blacksmith, given time,

but will not be pleased if kept long away

from his guns. Most gunsmiths will have

pet theories and grand schemes about

placement and use of guns in warfare.

These plans may be impractical or ingenious,

and once hired, a gunsmith will

attempt to get his plans implemented if

his employer seems rich enough to make

them reality.

Gunpowder

This explosive is an unstable mixture

of potassium nitrate (saltpeter), sulphur,

and charcoal. It does not travel well and

therefore was mixed on the battlefield.

Gunners were specialists in mixing

charges and judging the correct amount

of each ingredient to use, although this

too was at times more an art than a

science. Powder with coarse saltpeter

burned slowly; when finer saltpeter was

used, the powder exploded promptly

and with greater force. Many guns blew

up, and firing a charge through a touchhole

became suicide. Instead, gunners

laid a train of fast-burning powder along

the outside of the gun barrel, lit it, and

ran for safety.

The saltpeter is expensive and rare (in

the area of 22 gp per pound); the sulphur

less so (averaging 8 gp per pound). The

charcoal is cheap (1 cp for a 5-lb. bag)

and generally available, preferably from

the burning of willow wood. Willow faggots

cost 5 sp per cord (a cord can be

measured in many ways, but is usually

128 cubic feet). Local supply will of

course affect these prices.

The formula is generally 75% saltpeter,

15% charcoal, and 10% sulphur, but

these proportions vary if the powder is

used for blasting. One infamous use of

gunpowder is commemorated in the expression

“hoist with his own petard”: the

petard was a bucket of gunpowder the

gunner was supposed to take, dodging

arrows and the like, and hang on the gate

of a hostile stronghold (hammering in

his own nail to hang it on, if none were

handy) and then ignite, to blow in the

gate. It was not, as one can see, very

popular with gunners.

Guns

Medieval guns were of all manner of

names and calibers. Often individual

weapons of the same caliber made by

the same maker varied greatly in weight

and dimensions.

Some guns loaded through the breech

and others through the muzzle. They

were made of iron, steel, cuprum (hardened

copper or brass), latten (crude

brass), and “gunmetal” (or bronze, an

alloy of 90 parts copper and 10 parts tin).

Bronze was stronger than iron, but in

early examples of the alloy the proper

proportions of copper and tin were unknown;

smiths guessed, and as a result a

lot of bronze guns blew up.

Early guns (circa 1350) were small,

firing balls of up to 3 Ibs. weight, but by

1400 guns fired balls of up to 200 Ibs.

Smaller-caliber guns remained more accurate

than those of large caliber. The

largest known gun of this period was the

Russian “King of Cannons” built in 1502.

It had a caliber of 915mm, and fired a

l-ton missile down a 17-foot barrel.

Guns fired quarrels, balls of iron, brass,

and stone (sometimes strengthened with

iron hoops) and special treats like heated

shot (a wad of damp clay between the

powder and the ball prevented the gun

from exploding) and hollow shot filled

with gunpowder that was intended to

blow on impact. Cast iron balls replaced

stone (iron balls had more “punch”) but

were heavier, and had to be far smaller if

gunpowder was to hurl them with the

same force. Later. metal grew too expensive,

and stone balls were used in

quantity again.

Charles of Spain, in 1550, made the

first attempt to standardize gun calibers,

to let balls for one gun be used in another.

His artillery was of seven types. By

1753 there were nine calibers of English

guns, differing in size and weight depending

on whether they were iron or

brass. Confusion of size and exact statistics

is rampant, so the following tables

use the sixteen English gun types of the

mid-1500s. If these seem too exhaustive,

scale down the table as follows: handgun,

ribald, cannon, culverin, and saker

as is, and the listings of bombard (everything

larger than a Cannon), dolphin (everything

between culverin and saker),

and serpentine (everything smaller than

a saker). Listings follow in the Abbreviated

Table.

Names used in the table have been

applied (and misapplied) to all sizes of

guns by writers of various times, and

some names (such as “curtail” and

“sling”) belong to guns whose nature

and caliber are unknown. Culverin is Latin

for “snake”: guns were often named

for reptiles of mythology — the firebreathing

dragon became “dragoon.”

Early firearms Siege Attack: Points of damage

| Gun name | Cost (gp) | Avg.

wt. (lbs.) |

Wt. of missile (#) | Range (in game)

Min. |

Range (in game)

Max. |

Damage

S-M |

L | Rate of fire | Crew

(min.-max.) |

Caliber

(inches) |

Avg.

length ('/") |

Wood | Earth | Soft

Stone |

Hard

Rock |

Def.

point value |

| Handgun | 30 | 6 | 0.2 | 1 | 50 | 2-6 | 2-6 | 1/2 | 1-2 | 1 | 1'1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ribald | 380 | 804 | 0.2 | 1 | 50 | 2-62 | 2-62 | 1/243 | 1-3 | 1 | 4'5 | 1/2 | - | - | - | 1/2 |

| Rabinet | 200 | 300 | 0.5 | 20 | 200 | 1-10 | 1-10 | 1/2 | 2-3 | 1 | 3' | 1 | - | 1/2 | - | 1 |

| Serpentine | 400 | 420 | 1 | 50 | 600 | 1-10 | 2-12 | 1/2 | 2-3 | 1 1/2 | 4' | 2 | - | 1 | 1/2 | 2 |

| Falconet | 800 | 500 | 2 | 75 | 900 | 2-12 | 2-12 | 1/2 | 2-3 | 2 | 6' | 4 | - | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Falcon | 1000 | 800 | 3 | 100 | 1000 | 2-16 | 2-16 | 1/2 | 2-3 | 2 1/2 | 6'4" | 5 | - | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Minion | 1600 | 1200 | 4 | 120 | 1200 | 3-24 | 3-30 | 1/3 | 2-4 | 3 1/4 | 6'6" | 5 | - | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| Saker | 2000 | 1500 | 6 | 150 | 1600 | 3-30 | 3-30 | 1/3 | 3-5 | 3 1/2 | 7'9" | 6 | 1/2 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Bastard culverin | 2200 | 2600 | 7 | 170 | 2000 | 4-32 | 4-32 | 1/3 | 3-6 | 4 | 9' | 6 | 1/2 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Demi-culverin | 2300 | 3000 | 9 | 200 | 2200 | 4-32 | 4-40 | 1-3 | 4-6 | 4 1/4 | 11'6" | 7 | 1/2 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| Basilisk | 2400 | 3280 | 12 | 300 | 2400 | 4-32 | 5-20 | 1/4 | 4-7 | 4 3/4 | 11'8" | 7 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| Culverin | 2500 | 4000 | 18 | 300 | 2600 | 4-32 | 5-30 | 1/4 | 4-9 | 5 1/4 | 12' | 8 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Pedrero | 3000 | 4200 | 24 | 280 | 2500 | 5-20 | 5-30 | 1/5 | 4-11 | 6 | 9'6" | 8 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Demi-cannon | 3600 | 4500 | 32 | 260 | 2300 | 5-20 | 5-40 | 1/5 | 5-13 | 6 1/2 | 11' | 8 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Bastard cannon | 4000 | 5000 | 35 | 260 | 2200 | 5-30 | 5-40 | 1/6 | 5-13 | 6 1/2 | 10'11" | 9 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| Cannon serpentine | 4250 | 5600 | 38 | 260 | 1900 | 5-40 | 5-40 | 1/8 | 5-14 | 6 3/4 | 10'11" | 9 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 9 |

| Cannon | 4500 | 6000 | 40 | 250 | 1700 | 5-40 | 5-50 | 1/10 | 5-15 | 7 | 10'9" | 10 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 10 |

| Cannon royal | 4900 | 8000 | 68 | 200 | 1200 | 5-50 | 5-50 | 1/14 | 6-15 | 8 1/2 | 8'6" | 12 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 11 |

| Bombard | 5000 | 8000 | 2006 | 100 | 500 | 6-48 | 6-60 | 4/day | 7-15 | 126 | 12'+ | 14 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 12 |

1 Does not include the 2' stock.

2 This value is per barrel, of which there are 12; thus

total damage done is 2-6 (2d3), rolled twelve times.

3 Each barrel must be individually cleaned out, charged,

tamped, loaded, primed and lit (and the whole aimed). With two men, the

rate of fire rises to 1/12, or once every 12 rounds. A third man raises

it to once every 8 rounds. The rate cannot be further increased.

4 The ribald's weight includes cart.

5 This is its longest dimension; the ribald (with cart)

was 2' wide, 4' long, and 3' high.

6 Maximum value; smaller sizes possible.

<I have not included the Abbreviated Table, yet. Note that there is a weapon there named the Dolphin, which is not included in the above table.>

Firing guns

Gunpowder is a perilous substance

and handling a medieval gun was often

more dangerous than facing one. There

is a 10% chance (not cumulative) a gun

explodes when fired. (See AD&D

module

S3, Expedition to the Barrier Peaks;

treat the explosion as a grenade blast,

effective within 3”.) This chance is lessened

(-5%) if the gun crew is experienced

in handling the weapon in question,

and lessened further (-1%) if the

gun itself was successfully fired before.

However, if the gun has been fired 25

times without careful examination and

maintenance by a gunsmith, the chance

of explosion increases by 2% with each

additional firing.

The DM should take careful note of

other factors — such as flaming arrows

on a battlefield —that may affect premature

explosion. The most common cause

of such an accident was overcharging a

gun; that is, using too much powder. The

DM should judge when the gunner — by

mischance or upon instruction — has

used too much (a culverin requires 12

Ibs. of gunpowder per shot, smaller caliber

guns less, and larger caliber guns

more).

Basically, operating a gun includes

the following steps: Unload the gun from

its carriage, emplace it — the gunner ensuring

it is aimed — clean the barrel, mix

the gunpowder (this is generally done by

the master gunner while his crew positions

and emplaces the gun), load the

charge into the gun, wad it (to cap the

charge), tamp it (so the charge is packed

together and will burn quickly and evenly),

load and ram the shot, light the

charge by slow match, touchhole, or

powder trail, and head for cover before

the blast goes off.

After firing (assuming the gun and

some of the enemy and crew survive),

the gun must be re-aimed, the barrel

cleaned out, and the weapon reloaded.

Cleaning out all those barrels is why the

ribald (see table) has a low fire rate. Increasing

the number of people in the

crew can as much as double the firing

rate, but only so many men can work

around a gun before they start getting in

each other’s way.

Naval use of gunpowder

DMs should not allow successful waterborne

use of guns, confining gunpowder

to use in incendiary missiles

hurled by mechanical engines such as

catapults. Naval warfare can be fearsome

enough with this and “Greek fire,”

without using guns.

Men historically made fast work of the

problems of guns at sea, but the DM can

make the troubles insurmountable: Guns

are very heavy. They fall through damaged

decks and hulls, and can cause a

ship to roll over and capsize if they assume

unbalanced positions onboard.

Their recoil (before the days of traveling

carriages) was absorbed entirely by the

timbers of the ship, and the distressing

tendency of guns to explode destroyed

many vessels. Any vessel with a gun also

has an extremely vulnerable area: the

gunpowder magazine.

“Greek fire” was dreaded by ancient

and medieval sailors, and with good reason;

it burned on water and even damaged

stone and iron. The exact formula

is lost, but the terror weapon was liquid,

could be blown from tubes or encased in

missiles, and could be extinguished only

by sand, vinegar, or urine. It was probably

a mixture of naptha, quicklime, sulphur,

salt, petroleum and oils, and was

the heir of incendiaries used by the ancient

Greeks and Armenians (mixtures

of pitch, resin, and sulphur) and Romans

(quicklime and sulphur that ignited on

contact with water).

Even if guns are not carried on ships,

bear in mind that military men in the

AD&D world will be quick to place

them

onshore to defend harbors and strategically

important channels.

Strategic importance of gunpowder

Even when guns made more noise

than damage, they had a powerful effect

upon the behavior of horses and a lesser

effect on the morale of warriors. Despite

the expense and battlefield impracticality

of the guns, romantic, forward-looking

— and desperate — rulers will be most

interested in controlling the production

and use of guns (and gunnery).

In Piper’s Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen,

the priests of Styphon built an empire on

their control of gunpowder. Guns and

the knowledge of their construction were

of priceless strategic importance. The

success of Lord Kalvan, and historically

of John Zizka and of Gustavus Adolphus,

is due to putting their mastery of

this knowledge to battlefield use.

A DM may also consider guns of immense

strategic importance when a toococky

player character takes his Dragon

Slayer sword in hand and rides out upon

reports of a “a great snakelike monster

that belches fire with much noise” expecting

another rich treasure and easilyearned

level...

Gary on gunpowder

Dear Editor:

With regard to gun powder in the D&D® or

AD&D™ game systems, I wish to

point out the

following: The rules contain no provision for

the use of such materials. In general, gun

powder will not work. That is because it functions

on a scientific principle, and as every

adventurer knows, the fables of science and

technology are sometimes found in strange

areas, but the laws of magic are such that no

one can possibly believe in these arcane pursuits.

They never produce results.

E. Gary Gygax

Lake Geneva, Wis

(Dragon #66)

Dear Editor:

What the heck’s going on?! Ed Greenwood’s

attempt (“Firearms,” issue #60) to convince

AD&D players and DMs to change

this finely

designed game into a “historical simulation”

startled me.

Introducing firearms would dangerously

disrupt the balance of the game. Limiting firearms,

as Mr. Greenwood suggested, would be

nearly impossible because of probable experimentation.

There’s bound to be at least one

mad wizard in the crowd. AD&D might become

AG&G, Advanced Gunpowder and Gunslingers.

Why not just play BOOT HILL?

Keeping the true philosophy of the game

will keep the game more interesting and challenging

for both player and DM. What would

be the product of a game with guns that do

5-50 points of damage in a world where the

average person has 3 hit points?

Kwang Lee

Federal Way, Wash.

(Dragon #63)

Firing back

Dear Editor:

Kwang Lee’s letter (“Out on a Limb,” issue

#63) against Ed Greenwood’s “Firearms” article

(issue #60) appeared to jump to several

conclusions.

For one, Greenwood’s article was not an

attempt to change the AD&D system

into a

historical simulation. Gunnery would remain

more of an art rather than a science. Early

firearms were crude, cumbersome, and very

few in number. Their effect on the game as a

whole would be minor, as the guns’ use would

be extremely limited. Cold steel and magic,

rather than gunpowder, would remain as the

“great equalizers.”

Experimentation and further development

of these weapons should be firmly controlled

by the DM. Suggestions from the players can

be used, but development and use of major

firearms should be limited to NPC’s and the

DM. If players insist on expanding their armory

by developing gunpowder, a DM-invented

threat can be extremely persuasive in halting

such activity. Or, better yet, the DM can say

that the character’s gunpowder just doesn’t

work (due to wetness, improper mixing, etc.).

If a player persists, and the DM is feeling

particularly nasty, a percentage chance can

be used to determine if the gunpowder accidentally

explodes (a 500-pound charge of

gunpowder going off in a laboratory tends to

stop further research for a time). These methods,

both warnings and direct action, will prevent

“mad wizards” from abusing gunpowder.

Lee also complains about the use of a cannon

that does 5-50 points of damage when

normal people only have 3 hit points. Only a

fool would use an 8½-inch cannon against a

single normal person. A cannon of that size is

made to be used against forts, not people.

Besides, the 14 rounds it takes to reload the

8,000-pound monster is more than enough

time to get out of the gun’s line of fire, as they

cannot follow moving targets (they have

enough trouble hitting fixed ones as it is).

In combat situations, 5-50 is not as powerful

as it may seem. A medium-level (6th level)

magic-user spits out more damage in less

than one-seventh of the time (two fireballs for

6-36 each, or 12-72 total); a red dragon can

inflict up to 164 points of damage on a party in

a single round! This does not include the 88

points of breath weapon available to some of

these creatures. The 50-point maximum of

the cannon pales when confronted by this

whirlwind of power.

However, the final choice is up to the individual.

If gunpowder is used in a campaign

the DM should determine beforehand the

amount of the guns’ use and the extent of their

effect. A pre-set limit on the evolution of the

weapons and the DM’s firm control of their

use will make it impossible for the weapons to

disrupt the balance of the game.

Steven Zamboni

Sacramento, Calif.

(Dragon #65)

I agreed with S. D. Anderson's

comments in

"Forum," issue #164,

regarding wizards' possible

acceptance of gunpowder weaponry.

However, I

believe this acceptance would

develop slowly.

Wizards are orderly folk,

as close to today's

scientists as you can come

in the game. What

you did yesterday to produce

a magic missile

spell will work again today

in the precise same

way, and also tomorrow and

the day after. If

you do precisely the same

thing, the same

results will occur. However,

firearms in the

game world are far from reliable:

Sometimes

they work properly, sometimes

they don?t,

sometimes they even explode

in your face. I

believe this would produce

some rather natural

mistrust of gunpowder weaponry

on the part of

wizards.

Also, imagine the disarray

into which wizards

will be thrown when reports

of firearms first

come in. I?m sure most people

will refer, in the

beginning at least, to arquebuses

and flintlocks

as ?magic staves,? and pistols

as ?magic wands!?

After all, you point a firearm

at someone, a

flash and bang are produced,

and the victim

falls dead to the ground.

To the uneducated

masses, that is magic as

good as it comes!

This would certainly set wizards

and sages

alike on the wrong track

for the time being.

They will research files

for tales of powerful

magical items used by unknown

magicians

(probably the wielders will

not be magic-users

at all, but that is what

accounts might tell).

Putting new magical items

and new powerful

rivals together will certainly

cause havoc among

the ranks of Wizard Guilds

and independent

mages alike.

Nevertheless, this line of

inquiry will certainly

produce startling results,

as wizards start ?finding?

these new weapons. They will

certainly develop

magical and spell-driven

equivalents to firearms or

gunpowder. These magical

items will be far more

reliable than conventional

firearms, although

probably quite expensive.

I?m not talking of flintlock

pistol + 1, but a wand or

rod that behaves in

the same way. In fact, when

the use and knowledge

of firearms finally begins

to spread and we

get to see Anderson?s 98-pound

weakling mage

with his flintlock pistol

without amazement, these

magical equivalents will

certainly be the weapons

of choice of high-level wizards

throughout the

land. The flintlock pistol

will then be used by only

those mages not rich enough

(or not good enough)

to own one of those equivalents.

Of course, new

spells will also issue forth

from this phenomenal

research effort. The protection

vs. normal bullets

spell will certainly come

about, not to mention the

small shower over gunpowder

cantrip. Certainly

fighters and wizards alike

will benefit from the

introduction of gunpowder

to the campaign world,

even if it takes a while

for them to realize this.

W. Norgielix

Mexico City, Mexico

(Dragon

#175)