| Chagmat (Levels 1-4) | Deva | Smile! You are on fantasy camera! | The Bandit Kingdoms | Bandit |

| Point of View: The Humanoids | Campaign design: Plan before you play | Money: For the sake of change | FSS: The Barbarian | WG: Events of the Eastern and Southern Flanaess |

| LTH: Charisma | - | - | - | Dragon |

| <#62 | - | #63 | - | #64> |

Plan before

you play

Think it over, then map

it out

by Ed Greenwood

All too often in AD&D™

campaigns run

by novice DMs, the world

outside

the

dungeon is neglected or ignored altogether,

serving only as a universal

trading

post and safe resting place.

Most of

the scope that the AD&D

game offers is

thus lost; many such campaigns

grow

dull (despite the DM’s frantic

attempts to

introduce more terrible

monsters and

more enticing treasures)

and die.

The traditional advice handed

to a novice

DM who realizes what is

happening

(or fated to happen) to

his game, is: pick

up the WORLD

OF GREYHAWK™ Fantasy

World Setting or The City

State of the

World Emperor by Judges

Guild, or a

similar product, and “do

it that way.”

This approach can mean failure

for the

poor DM if one of the players

has access

to the same material, or

if the party begins

to go off on a tangent into

an AREA or

topic not covered by the

role-playing aid

— and in any case the USE

of such products

limits the variety

of play, landing

the DM back in the same

situation once

the players “use up” or

grow bored with

the module. None of these

products tell

the DM how to set play in

motion, or how

to build in contacts and

activities to give

the party a variety of things

to do.

Len Lakofka, in his columns

in issues

#39

and #48 of DRAGON™ Magazine,

has taken the traditional

route of advising

how much and what type of

treasure

and monsters should be thrown

at the

fledgling party, and doing

this correctly

is indeed essential to the

creation of a

long-lived, balanced campaign.

But many

DMs give their players a

feeling of being

lockstepped through a sequence

of contrived

events, a single carrot

held ever

before their noses, with

blank emptiness

on either side. That is,

the players have

only one course to take

in all circumstances,

either because the DM is

forcing

the players into certain

actions by

having his world act upon

them (i.e., “ten

assassins suddenly ambush

you,” or

“there’s an umber hulk between

you and

the exit, and it’s advancing,”

or “the king

sends for you and orders

you to go forth

and slay the bandit lord

— bring his head

back in ten days or be hunted

and slain

by the royal soldiers”)

rather than allowing

them — the exceptional heroes,

remember?

— to act upon the world.

Such “you must do this”

tactics are a

necessary part of any DM’s

bag of tricks,

true— but if the DM uses

them constantly,

players tend to get fed

up, and the

campaign proves short-lived.

Many DMs

have no problem adding depth

to their

games, but this is written

for those who

like a guiding hand or are

looking for

new ideas. One DM I know

runs a “roleplaying

first and foremost” campaign

set

in a desert city. We’ve

had great fun playing

on nights when no character

drew a

sword and no dice were rolled;

we merely

bargained and dealt with

others in the

city, following up many

mysteries and

intrigues. When violence

does occur in

such a game environment,

it is memorable

and not humdrum hacking,

the way

campaign play should be.

Setting up such a campaign

is simple

— but it is a long task.

Take the time; it

(or the lack of it) will

show. First, list the

settings, characters, and

situations you

want to include in play.

Then put them

on a map. Consult geography

texts if

you’re unsure about the

positioning of

geographical features. The

simple rules

of thumb to remember are:

rivers run

from mountains to sea, the

largest cities

are found where navigable

rivers and sea

meet, and fortresses or

cities are also

constructed at other strategic

locations

(mountain passes, bridges

or fords of

wide or deep rivers on important

travel

and trade routes, and good

harbors along

the seacoast not adjacent

to a river).

Good agricultural land is

necessary to

support large cities and

a high standard

of living. The supply of

raw goods, particularly

metals, also governs the

standard

of living and the prices

of everything

the characters must buy.

Once you have a map, trade

routes

(and from them, political

forces) are immediately

apparent, and the character

of

your world is thereby established.

Then

a host of modifying factors

(such as traditions

and past political history,

racial

distribution, and religious

beliefs) must

be added. The easiest way

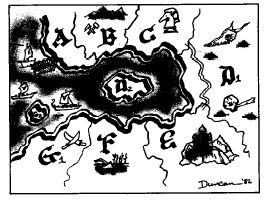

to illustrate

this is with a sample; see

the map accompanying

this text.

Crude, eh? It can be prettied

up later,

as Gollum would say. The

letters stand

for regions (kingdoms, if

you prefer)

governed from large coastal

(port) cities

(the triangles). Each can

be described

simply:

A (which we’ll call

Alut; pronounced aloot) is a country of

fishermen and artisans;

old, superior, and with visions of building

an empire, but low on resources.

B (Barsheba) has

rich mines in the mountains far to its north.

C (Cluf), the “caravan

city,” raises good horses (or equivalent

beasts of burden) in its

provinces.

D-1 is desert; harsh,

vast, and unable to support life. The

nomads sometimes encountered

here use ruined desert cities

as bases, but live in the

steppes far to the north of Cluf.

D-2 is Darshin, a

rocky island with little agriculture of its own,

but a strategic location.

E (Emmersea) is a

relatively new land built on the ruins of an

earlier civilization; the

scene of much old magic and odd

events.

F (Famairal) is a

land of successful farmers; rich in produce,

poor in lumber and metals.

G-1 (Geldorn) is

a wild, rocky country of fishermen, necessarily

a naval power. Its interior

is a savage country, but many

enter to seek the gems found

in the mountains far to the south.

G-2 (Ghed) is an

island currently held by Geldorn.

From these few threadbare

descriptions,

we can build in forces of

activity;

the tensions, trade, and

interests which

are the life of any world.

The sea and the

desert are the two natural

obstacles to

trade, and so there is an

important overland

caravan route between Cluf

and

Emmersea — imperiled by

the nomads,

of course. There is also

naval trade: Darshin,

because of its location,

is the foremost

sea power, but it is weak

in resources

and needs goods from the

other cities

to survive. Alut is also

hungry for resources,

has a good port, and desires

to

expand over “the barbarian

kingdoms.”

Said kingdoms (D, E, F,

and G) aren’t too

pleased at the idea; Geldorn,

in fact,

fears both Alut and Darshin,

and heavily

guards the isle of Ghed

to preserve its

naval power and independence.

Geldorn

is at the very end of the

horseshoeshaped

caravan route, is valued

for its

gems, and is not a country

suited for

overland travel.

Politics (social mores)

and codes of

conduct are matters best

dealt with in

detail at another time,

but at a glance one

can see that the government

of Alut

would be a matter of pompous

trappings

and hallowed traditions,

that of Barsheba

would be close-armed force

to guard

the mineral wealth of the

country, that of

Famairal would be the most

easy-going

by virtue of a widely accepted

code of

behavior (to wit, the necessary

tasks and

customs of farming the land),

and those

of Cluf and Emmersea would

be the most

open and tolerant due to

their “crossroads”

aspect, perhaps having only

a

“Trader’s Code” of some

sort.

Darshin and Geldorn will

probably be

armed camps; the strategic

importance

of Darshin means its independence

would last only as long

as its navy was

the most formidable on the

seas. This

warlike stance is balanced

against the

fact that the isle requires

goods from the

other countries to survive,

and by the

fact that the pirates and

the navies of all

the other countries could

in combination

defeat it, if Geldorn attempted

any conquests.

As it is, there is strife

between the

Darshin trading vessels

(who charge

trade rates to the other

countries of sufficient

amount to maintain the existence

of overland trade) and those

of Alut, who

are trying for a share of

cargo-carrying

fees — and between both

of these and

the pirates of the isle

of Ghed, who are

preying on both navies and

keeping

them both too weak to defeat

the other.

(If one did achieve supremacy,

it would

of course then turn and

crush Ghed.)

A lively situation for adventuring,

and

two countries in particular

seem ideal

sites for a party of adventurers:

Geldorn,

with a government whose

reach and attention

is turned outward and not

into

the wild (monster-populated)

interior,

and with gems to be found

which lure

adventurers, merchants,

and even official

agents from all countries;

and Emmersea,

a land of small villages

or dales

lightly governed by merchant

lords. Of

necessity (so as to not

discourage trade),

government and law enforcement

in

Emmersea will be light.

Emmersea’s terrain

of small valleys makes for

a choice

of trade routes within the

country, adventurers’-

type terrain, which can

support

small settlements easily

handled by

a DM. The fact that the

country is marked

with the ruins of earlier

civilizations provides

a setting for (and a market

for the

rewards of) adventuring.

If agriculture is

crowded into the valleys

and the slopes

around the valleys are heavily

wooded,

Emmersea has an exportable

good:

lumber for the wagonmakers

of Cluf and

the shipyards of Darshin,

and a need for

textiles and other goods

possible only

when agricultural land is

plentiful and

good.

Aside from the acknowledged

authority

of the governments, there

will be many

other power groups in this

world. The

merchants not governing

Emmersea and

Cluf are one such group

— or, more

probably, they comprise

many groups.

Others will be rebels, opponents

of the

governments of all types

— perhaps

giants or the goblin races

in the mines

and mountains of Barsheba,

having been

pushed out by men and angry

about it.

Religious groups — some

allied to the

local government, some opposed

— are

other sources of power; so

are the intellectuals,

philosophers and inventors,

particularly when technology

and progress

is not sponsored or favored

by the

state.

Technology, religion, and

accepted

authority (laws, customs,

and tradition)

will provide much of the

impetus, directions,

and limitations on adventure

for

the players; the DM must

take care with

the development of these

things and

concepts. The restrictive

tenets of a religion,

for example, can affect

trade. If

Geldorn embraces the druidic

faith, it

will not be the scene of

legal logging

operations, nor will its

borders likely be

open to those carrying lumber

or caged

wild animals being transported

over land

or sea.

Much of the activity of

the campaign

will come from the ongoing

struggles between

various power groups; for

example,

the G and D series AD&D

modules

put out by TSR Games depict

a world of

various groups (ogre magi,

the hill giants,

frost giants, fire giants,

kuo-toa, illithids,

Lolth-worshipping and elemental

godworshipping

drow nobles) all cooperating

to a degree, and at the

same time

vying for supremacy. A party

will unavoidably

make allies and enemies

as

they take action in the

midst of such conflict,

and members of the party

may even

join (opposing?) groups

and find themselves

directly involved.

The DM should also determine

the

prevalence and nature of

the ruins of

previous civilizations.

Not only are these

necessary for the location

of artifacts

(many of which, the DMG

tells us, are of

construction and origin

now unknown)

and as a justification for

the existence of

“dungeons,” but they can

possess a fascinating

aura of grand mystery. As

players

of the GAMMA WORLD™ game

know,

exploring the leavings of

the past is dangerously

alluring —and players in

more

medieval-style AD&D

settings usually

enjoy burial sites, stone

circles, and the

like. Secret (evil, or opposed

to the accepted

— state? — religion) cults

can

worship at such places,

and treasure can

be hidden there; both are

often hinted at

by local legends of magic,

apparitions,

and otherwise strange doings.

In our sample world, Emmersea

is the

chief locale for such ruins

and old landscapes,

although ruins can be placed

in

any wild areas (such as

Geldorn’s interior,

the desert, and the mountains

in all

countries), and such areas

would logically

be populated by various

non-human

races and creatures. Alut

might have artifacts

preserved in its great towers

and

tombs, but these would be

rare in Barsheba,

Cluf, and Famairal, where

magic

items would long since have

been found

and destroyed or carried

off.

Yet another factor can be

added to a

world: that of “other-world

connections.”

Connections with other planes

and other

“worlds” (parallel Prime

Material planes)

allow a DM to use many monsters

and

characters (such as those

found in this

magazine’s Giants In the

Earth column),

and limited experiments,

such as characters

from futuristic and modern

settings,

that otherwise could not

be justified.

The presence of an “other

world”

gives the DM ample justification

to end,

or retract, elements that

don’t add fun to

play, or that threaten the

balance and/or

cohesiveness of the campaign.

In my own “Forgotten Realms”

campaign,

similarities between the

world we

all live in and the AD&D

fantasy world

(such as chronology, fighting

tactics,

and legends of beasts such

as dragons

and vampires) are all accounted

for by

the existence of connections

between

the two worlds. These connections

were

once well and often used,

but are now

largely forgotten (hence,

“Forgotten

Realms”) by those on our

side (uh, that

is, this side, the modern

one, with the

progress and pollution and

such...). But

some few quietly walk our

earth who

know the Realms well. .

. .

Control of the means of

interplanar

travel (see the AD&D

Players Handbook,

Dungeon Masters Guide, and

my article

on gates from issue #37

of DRAGON

Magazine, reprinted in the

BEST OF

DRAGON™ Vol. II collection,

for details)

will be of immense strategic

importance,

and all who know of them

will join in, or

at least take sides in,

the struggle to control

the “gates” and gate mechanisms

at

some point. One idea for

a long-lasting

campaign is that of a powerful

mage or

group of beings opening

up, re-opening,

destroying and creating

a group of gates

between various alternate

Prime Material

planes and the Outer Planes,

using

these as bridgeheads for

invasions of

creatures from these other

planes, in the

same manner as Lolth is

expanding into

the mountainous, icy world

in AD&D

module Q1, Queen of the

Demonweb

Pits. A party could find

such a group to

be a numerous, widespread,

and powerful

foe which could work behind

many

day-to-day events and adventures.

Such gates could be placed

in our

sample world in hidden valleys

in the

north of Cluf, for example,

with quiet interplanar

caravan trade taking place;

or

an invading force of monsters

from some

other plane could be issuing

from a gate

in a ruined city deep in

the desert, under

the guidance of lamia. Strange

ships

could be encountered, arriving

at Alut

and Darshin, or washed up

piece by

piece on the remote western

shore of

Geldorn — perhaps coming

from another

plane through a seaborne

gate, perhaps

hailing from a hitherto

unknown

western continent, or the

fabled Far Isles

— if a DM works at it, the

possible directions

he offers the players for

play to

proceed in are almost endless.

A contact with another continent,

for

example, offers enterprising

characters

a chance to found a trading

company

operating between the known

kingdoms

(A-G) and the new continent,

with all the

attendant headaches and

rewards. This

leads us to another topic:

employment.

In law-abiding areas (Alut,

Barsheba,

Darshin, and Famairal),

few free-booting

adventurers are going to

be tolerated. A

visible means of income

is necessary; at

least some of the party

members must

have honest jobs. Too few

DM’s explore

this facet of the game,

preferring instead

freewheeling, fiercely independent

player

characters who live off

the work of others

(the lot of a privileged

few, mostly

hereditary nobles, in the

medieval-technology

societies found in most

AD&D

campaigns).

If a DM lacks the time or

the confidence

to work out a detailed social

situation,

or wishes to utilize commercial

modules

when placing them in his

existing

world would disrupt affairs

greatly, the

“Anchorome campaign” is

a solution.

This campaign, named for

a legendary

island far over the sea

to the west, further

from the mainland than most

sailors ever

dare to go, is simplicity

itself. The party

is provided with — hired,

conscripted,

ordered, or bequeathed —

a ship. This

vessel (if properly maintained)

is adequate

for them to live on, and

to carry a

respectable amount of trade

cargo. Due

to the menace of pirates

or warships, or

because of a storm, or because

rumors

of treasure are eagerly

followed by the

party, the ship is sent

off the normal

trade routes into the unknown.

Play can include a single

voyage, like

that of C. S. Lewis’s Dawn

Treader, or

(like the owners of a Traveller

free trader)

the party can carry on voyages

for

many years, concerned with

trade, continually

provisioning and maintaining

the

ship, avoiding seizure and

shipwreck,

and so on.

The setting (an unknown

sea dotted

with islands) allows use

of all marine

AD&D monsters and many

published

role-playing aids, from

Judges Guild’s

Island Books through D&D®

Module Xl,

the perfectly suitable Isle

of Dread, to

AD&D modules like C1,

S1, and S3. The

island in the A series modules,

modified

somewhat, could also be used.

The DM

merely charts the immediate

vicinity of

the party’s ship, determines

aquatic

monster and ship encounters,

and locates

whatever is desired (from

modules,

magazines, current reading,

and creative

thought) on islands — or

upon the

vast backs of sleeping whales,

for that

matter! When DM or players

tire of the

setting, the DM creates

a nearby continent

or an interplanar gate upon

an island,

and the campaign setting

can shift

overnight.

Whatever the precise campaign

setting,

the success of play depends

upon

the players and the skill

of the DM — in

particular, the care and

extent of the

DM’s work outside of actual

play. A sterling

example of the depth displayed

by a

well crafted, detailed world

— and the

“life” such a world seems

to take on — is

in Tolkien’s Unfinished

Tales. A few

areas of special importance

and concern

in world-making will be

discussed below

and in future articles.

The Dungeon Masters Guide

warns

the DM that time records

must be kept in

any meaningful campaign;

too few DMs

realize this (or bother

to undertake the

work to make it so), or

that this timekeeping

should be extended to the

movements

and activities of all rulers

and other

important NPCs, the locations

of all

active and potential warriors

(particularly

mercenaries), valuable trade

goods,

and the ongoing enactment

of political

policies, orders, encounters

and the

spread of information —

not just to the

training times and monetary

expenditures

of the player characters.

The lure of the lost and

forgotten is an

interest-producing facet

of play well

known to most DMs, at least

on the level

of the hunt for buried treasure.

But few

see the potential of ancient

records, histories,

and tomes of lore as a source

of

hints to treasure location,

clues to the

identity and present whereabouts

of

now-dead (or undead) kings,

magicusers,

and other important individuals,

partial spell or artifact

knowledge, and

background lore.

The DM can have great fun

composing

such works, the players

will gain much

from them, and play should

improve.

Too many players find (and

survive the

opening of) books in dungeons

only to

find that they hold yet

another illegible

diary or accountant’s ledger

— or worse

yet, expect from experience

that every

book found will be a spell

book or magic

item (Book, Codex, Grimoire,

Libram,

Manual, or Tome) from the

DMG.

Many DMs miss a great chance

to

spice up play by slighting

an entire character

class: thieves. Too many

thieves

are played as door-openers

and lockpickers

for those rare occasions

when

the swashbuckling blast-and-hackers

who make up the party feel

an attack of

caution — and their thievery

tends to be

either pocket-picking and

corpse-strip-

ping, or of the snatch-and-run

variety.

The DM should ensure that

such performance

carries much risk, but enjoys

only limited success — a

thief who seeks

wealth (and advancement

in levels)

should keep such risky,

bandit-like activities

to a minimum, preferring

instead

careful planning of thefts.

The target

must be watched, specific

tactics devised

to overcome defenses and

obstacles,

escape routes and a location

or

means for the quick disposal

of loot to

avoid discovery be settled

upon — a

stupid or reckless thief

who does not

keep on the move should

be a short-lived

creature, and player characters

are, after

all, supposed to be a cut

above the norm.

Only one more topic is essential

in a

DM’s primer — politics.

Aside from personal

feuds and rivalries, there

is always

a struggle for power surrounding

the government

of any kingdom worth having.

The legitimate king is dead,

perhaps, or

senile —and his three known

sons (plus

another two claimants who

may be illegitimate

sons of the king or only,

however

unwittingly, impostors)

all battle for the

throne; in the political

arena of councils

and by wooing various nobles

or power

groups as patrons, and then

increasingly

by means of daggers in dark

corridors

and bared swords on the

high roads.

The players, as all others

in the land,

must choose sides in this

struggle, and if

their choice is ill they

may fare accordingly.

Such a war of succession

(as illustrated

in Roger Zelazny’s Amber

series,

for example) may go on for

years, as rival

claimants go into hiding,

emerge to win

the throne in a bloody ambush

or midnight

murder, and fall in their

turn to the

next usurper . . . and of

course, a kingdom

so weakened will be inviting

to neighboring

states wishing to expand,

or the nonhuman

tribes who have bided their

time

in the mountains, forests,

and swampy

valleys of the north, waiting

to reclaim

the land that was once theirs.

Many local

officials and minor nobility

will seize this

chance to gain wealth and

power in the

face of uncaring chaos at

the capital, and

these small-scale governors

will rule the

affairs of various small

areas of the kingdom

by the weight of their swordsworn

(men pledged to service).

A royal struggle need not

be so widespread,

however; some such struggles

will never actively pass

beyond the walls

of the palace, such as the

nasty situation

which arises when the monarch’s

eldest

child is female, and a younger

brother

(as the eldest male descendant)

believes

he should have the throne.

If the DM does not favor

large monsters

or wilderness adventuring,

a vast,

complex castle with forgotten

passages

and dungeons (like the fictional

Gormenghast

or Amber) and old, manylayered

intrigue may prove an ideal

dungeon

setting — the players need

never

even see the light of day.

If one thinks a

castle setting limiting,

consider the action

action

in Howard’s Red Nails or

Goldman’s

The Lion In Winter, or the

possibilities,

offered by the half-ruined,

labyrinthine

citadel in Wolfe’s Shadow

of the Torturer.

Understanding why one kingdom

is

stronger than or opposed

to another,

and why one mountain pass

is strategically

important and another not,

is essential

to the DM, if players are

to affect

the status quo without always

coming

into direct contact with

(or becoming)

rulers. An endless diet

of kings and princesses

and wicked nobles reduces

the

excitement and interest

of the trappings

and traditions of power

and, if the DM

can’t come up with alternatives,

dooms a

campaign to increasingly

dull and bland

play.

A good guide for the novice

DM to

judge the depth and interest

of his or her

campaign is to consider

its elements and

events without the players

(and their

characters and deeds). Is

the setting, bereft

of player involvement, still

interesting

enough to be the stuff of

which tales

are made?

If not, something must be

done. And

yet the action of the world

must not be

entirely divorced from the

actions and

interests of player characters

— the play

of the campaign must be

concerned with

them, and the overall tapestry

of events

in the world should be affected

by them,

moreso as the characters

grow in experience

levels and the players in

playing

experience. On the other

hand, the DM

must avoid any tendency

of events to

halt in mid-action when

adventuring

stops, coming to life only

when player

characters walk onstage

to do battle. (I

always thought it odd that

enemies would

lay low at the same time

as player characters

trained or recovered from

wounds,

and that no one fell upon

the unprotected

treasure of player characters

while

they were off training.)

Note that players need not

be made

aware of all the DM’s work

in creating

nearby characters, groups,

and activities.

They can learn what they

will as play

proceeds; indeed, a degree

of mystery

builds interest more than

any other quality

of a campaign. Too much

will frustrate

players, however; the DM

must find

the proper amount, while

bearing in

mind that several small,

simultaneous

mysteries are better than

one Grand

Mystery after another. Mysteries

also

leave a DM room to modify

his campaign

to respond to player desires

and achievements,

and to avoid or explain

a way

around apparent contradictions.

And every long-running campaign

will

have such “gray areas,”

no matter how

intricately developed it

is before the

onset of play; for six days

a DM labors

mightily to create a world

and breathe

life into it, but the world

he creates is

(alas) not perfect, and

by the seventh

day that DM has certainly

earned a

rest....

| Psionic Ability | Attack Modes | Defense Modes | Minor disc. | Major disc. |

| 2-40 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 41-80 | 1 | 1 | 1-2 | 0 |

| 61-80 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-3 | 0 |

| 81-100 | 1-3 | 1-3 | 1-4 | 11 |

| 101-120 | 1-4 | 1-4 | 1-4 | 12 |

| 121-140 | 1-4 | 1-4 | 1-4 | 13 |

| 141-160 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1 |

| 161-180 | 2-5 | 2-5 | 2-5 | 1 |

| 181-200 | 2-5 | 2-5 | 2-5 | 14 |

| 201-220 | 2-5 | 2-5 | 3-6 | 15 |

| 221-240 | 2-5 | 3-5 | 3-6 | 2 |

| 241+ | 3-5 | all | 3-6 | 2 |

1 -- only if 4 is rolled for minor disciplines

2 -- only if 3 or 4 is rolled minor disciplines

3 -- only if 2, 3, or 4 is rolled for minor disciplines

| MINOR DISCIPLINE | INT | WIS | CHA | NONE | ALL |

| Animal Telepathy | 01-02 | 01-03 | 01-04 | 01 | 01-03 |

| Body Equilibrium | 03-07 | 04-05 | 05 | 02-03 | 04-05 |

| Body Weaponry | 08-11 | 06 | 06-07 | 04-08 | 06-07 |

| Cell Adjustment | 12-13 | 07-14 | 08-10 | 09-12 | 08-10 |

| Clairaudience | 14-17 | 15 | 11 | 13-14 | 11-14 |

| Clairvoyance | 18-20 | 16 | 12 | 15-16 | 15-17 |

| Detection of Good or Evil | 21-22 | 17-22 | 13-19 | 17-18 | 18-20 |

| Detection of Magic | 23-30 | 23-24 | 20 | 19 | 21-22 |

| Domination | 31 | 25-29 | 21-30 | 20-22 | 23-25 |

| Empathy | 32-33 | 30-32 | 31-34 | 23-24 | 26-28 |

| ESP | 34-39 | 33-35 | 35-37 | 25-26 | 29-32 |

| Expansion | 40-43 | 36-38 | 38-40 | 27-39 | 33-36 |

| Hypnosis | 44-45 | 39-45 | 41-55 | 40-42 | 37-40 |

| Invisibility | 46-54 | 46-52 | 56-58 | 43-50 | 41-45 |

| Levitation | 55-56 | 53-55 | 59-60 | 51-60 | 46-48 |

| Mind Over Body | 66-68 | 56-67 | 61-66 | 61-70 | 49-53 |

| Molecular Agitation | 69-77 | 68-69 | 67-68 | 71-74 | 54-57 |

| Object Reading | 78-83 | 70-76 | 69-73 | 75-76 | 58-67 |

| Precognition | 84-88 | 77-85 | 74-76 | 77-78 | 68-79 |

| Reduction | 89-90 | 86-88 | 77-81 | 79-84 | 80-83 |

| Sensitivity to Psychic Impressions | 91 | 89-95 | 82-86 | 85-86 | 84-88 |

| Suspend Animation | 92-98 | 96-98 | 87-94 | 87-99 | 89-92 |

| (Select one) | 99-00 | 99-00 | 95-00 | 00 | 93-00 |

| MAJOR DISCIPLINE | INT | WIS | CHA | NONE | ALL |

Title

S