| - | - | Runic Inscriptions | - | - |

| Dragon | - | Races | Best of Dragon, Vol. IV | Dragon 69 |

One night Elminster and I were sharing what fantasy writer Lin Carter

calls a

“round of converse” (the sage has acquired a weakness for pina coladas,

a

beverage unknown in the Realms from

whence he comes), and our talk turned

to the dwarves.

Elminster thought the picture of the

Hill Dwarf in the AD&D™

Monster Cards

very striking. While he was admiring it,

your wily editor asked if he knew of any

written dwarvish records: tomes of lore,

for instance, and, ahem, magic. Elminster chuckled and reached into

one of

the many pockets in his voluminous

robes (yes, I know he looks odd, but the

neighbors think I’m strange anyway),

coming out with his pipe and pouch —

and a stone, which he handed to me.

“Dwarves seldom write on that which

can perish,” Elminster said, lighting up.

“Rarely, they stamp or enscribe runes on

metal sheets and bind these together to

make books, but stone is the usual medium: stone walls in caverns,

stone buildings, pillars or standing stones — even

cairns. Most often, they write on tablets

— ‘runestones,’ as we call them in the

Common Tongue.”

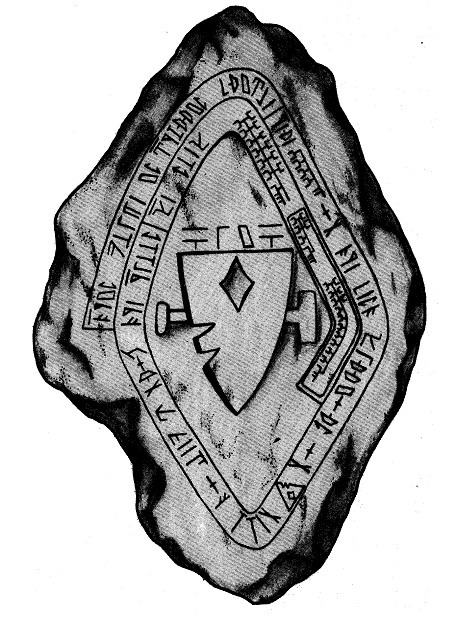

The stone I held was flat and diamondshaped, about an inch thick, and

of some

very hard rock I did not recognize. It was

deep green in color, polished smooth,

but it was not, Elminster assured me, any

sort of jade. The face of the stone was

inscribed with runes in a ring or spiral

around the edge (see illustration), and at

the center bore a picture. Some runestones have pictures in relief,

and are

used as seals or can be pressed into wet

mud to serve as temporary trail markers

underground.

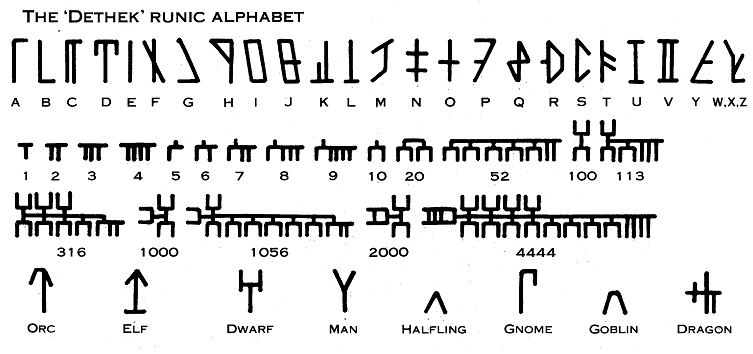

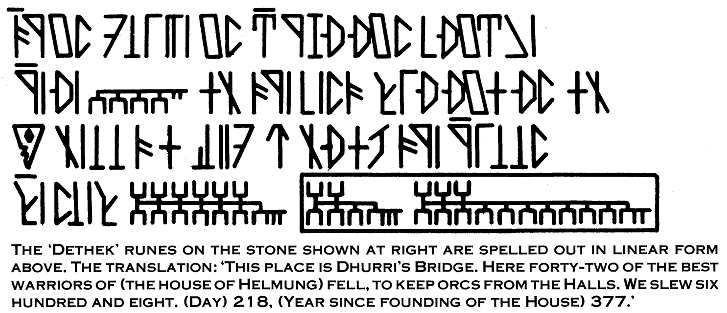

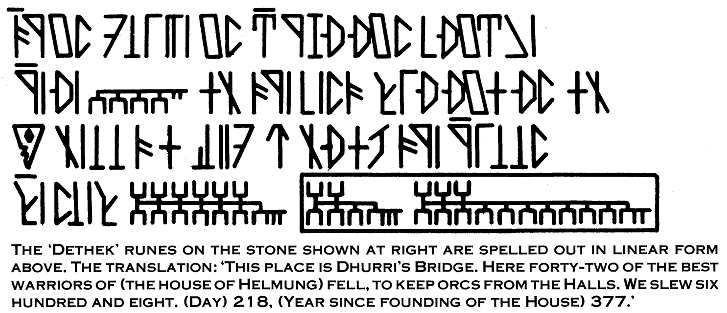

To a dwarf, all runestones bear some

sort of message. Most are covered with

runic script; Elminster knows of three

such scripts. One of them, known as

“Dethek,” translates directly into Common, and all of the stones he

showed me

that night and subsequently were in this

script. The runes of this script are simple

and made up of straight lines, for ease in

since the sound it makes in a word can

be expressed by an “s” or “k” character.

Players and DMs have to consider

what sorts of materials and techniques

are available for scribing or writing the

runes onto a surface. Geography will

have an effect on available materials, just

as it did with the Germanic tribes. Tree

limbs and large rocks, for instance, were

in abundance where the Germanic tribes

lived. In a fantasy environment that contains large trees and rocks,

these would

be obvious and often-used surfaces for

carving. But in a world devoid of trees or

rocks (a distinct possibility in a fantasy

milieu), choices for a carving medium

would be restricted to other suitable

materials that are available.

Runescan be carved on manufactured

items — rings, weapons, gauntlets, and

so forth. Even a world that doesn’t contain an abundance of suitable

raw materials will have weapons, magic items,

and other things that can be inscribed.

Runes can be written (applied upon a

surface instead of being etched into it)

on almost any material that will accept

ink, pigment, charcoal, or other writing

mediums. Parchment, animal hide, or —

for the very lavish — vellum (calf’s hide

finely tanned and scraped) will hold ink

from a quill or pigment from a brush.

Historically, certain techniques were

used in the configuration of rune characters in or on a surface. On

free-standing

stones (rune-stones), the characters

were often carved between parallel borders in the form of a winding

“snake”

design which served to embellish the

work and make the stone more attractive. A less artistic method of

carving was

to simply put down the characters in

“rune-rows,” set off from one another by

straight horizontal lines, often spaced so

that the tops and bottoms of the rune

characters touched the lines.

Words were not usually set off by spaces between them; rather, one

would be

separated from the next by a dot or a

small “x.” Words were also distinguished

by painting them in different colors, but

if the coloring washed away or was worn

away, the message could become rather

cryptic. According to many legends (including Egil’s Saga), the magic

of runes

would not work unless the writing was

smeared with blood.

As with any other subject that has a

foundation in history, the concept of

runes can be adapted by players and

DMs for use in a fantasy role-playing

game, without necessarily remaining totally faithful to the way runes

were used

in history. Perhaps a runic alphabet will

be developed into the most widely used

form of communication in a fantasy

world. Or, perhaps the “art” of scribing

runes will be only partially developed

and known only to a select few. Any system is appropriate, as long

as it’s logical

and as long as it “fits” in the world for

which it was designed.

cutting them into stone. No punctuation

can be shown in Dethek, but sentences

are usually separated by cross-lines in

the frames which hold the lines of script;

words are separated by spaces; and capital letters have a line drawn

above them.

Numbers which are enclosed in boxes

(within the frames) are dates, day preceding year by convention. There

are

collective symbols or characters for

identifying peoples (clans or tribes) or

races. If any runes are painted, names of

beings and places are commonly picked

out in red, while the rest of the text is

colored black or left as unadorned

grooves.

Runestones are commonly read from

the outer edge toward the center; the

writing forms a spiral which encloses a

central picture. In the case of the stone

illustrated here (Elminster said this stone

came from a place now destroyed), the

crude central picture identifies the writer

as a warrior (the hammer) of the House

of Helmung, now thought to be extinct.

(His name, “Nain,” is written above the

shield of Helmung, as is the custom. A

dwarf of some importance would place

his personal rune here.)

Runestones telling a legend or tale of

heroism usually have a picture of the

climactic scene described in the text;

grave markers or histories usually reproduce the face or mark of the

dwarves

described. The central symbol may also

be a commonly understood symbol (e.g.,

a symbol of a foot for a trail marker, or an

inverted helm to denote safe drinking

water), or sometimes nothing more than

simple decoration.

Runestones serve as genealogies and

family burial markers, Elminster told me,

and to record tales of great events and

deeds of valor. They may be inventories

of the wealth of a band, or private messages which would be meaningless

to

all

but a few individuals.

One stone was found in a labyrinth of

dwarven caverns cut into a mountain

range, serving as a very plain warning

— to those who knew the script — of a pit

trap just beyond. Another, somewhere in

the same abandoned dwarf-halls, is reputed to hold a clue to the whereabouts

of the Hammer of Thunderbolts once

borne in the Battle of the Drowning of

Lornak.

“But you,” Elminster said, looking innocently up at the smoke rings

slowly

rising in the evening sky above his rocking chair, “will as usual be

most interested in treasure.” I made him another

drink, and in silence we watched the fireflies play around the garden

fountains. I

waited, and finally he spoke. “Apart from

those stones that are treasure maps —

usually directions hidden in those cryptic verses people write when

they think

they’re being clever — a few stones are

themselves magical, or adorned with

gems.”

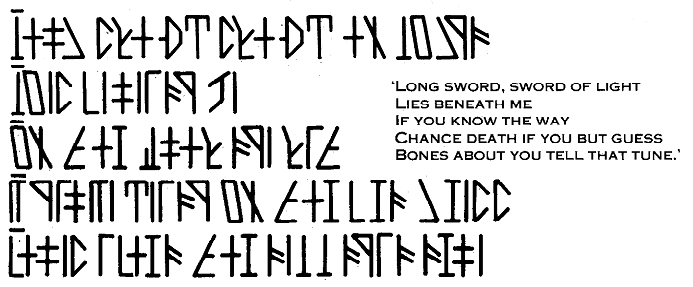

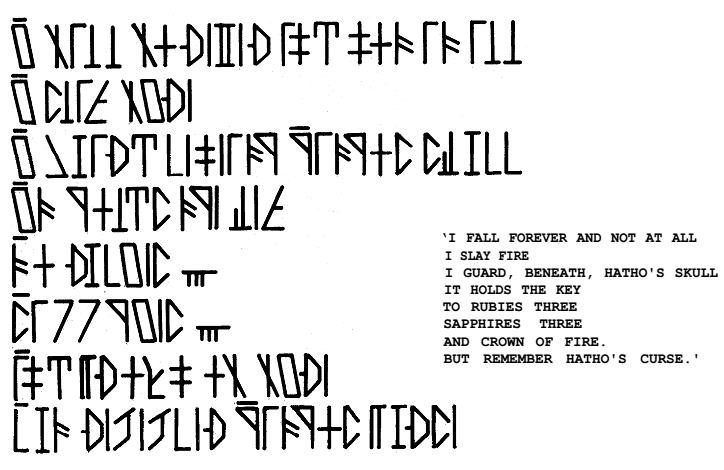

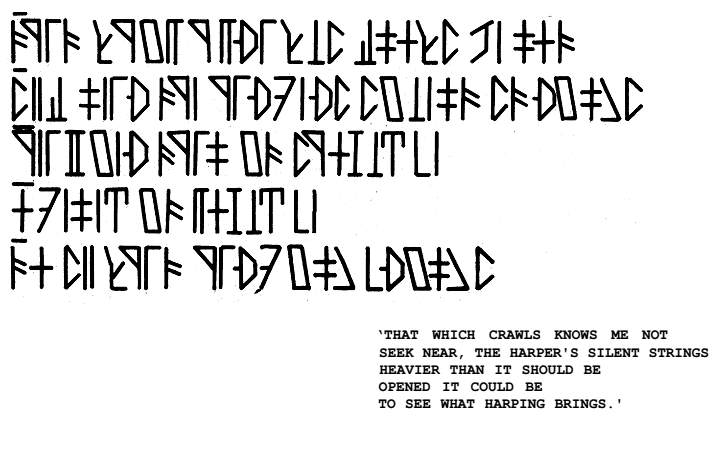

Later meetings with Elminster yielded

three examples of “treasure-map” stones

(the text from which is reproduced here),

and two examples of magical stones: a

record in the Book of Passing Years that

mentions a runestone that functions as

an Arrow of Direction, and almost forty

references in the folk tales and ballads of

the northern Realms to runestones that

spoke (via a magic mouth spell) when

certain persons were near, or when certain words — sometimes nothing

more

than nonsense words inscribed upon the

stone itself, to be read aloud — were said

over it.

Some non-magical runestones contain

warnings, or poetry, but most often their

songs are treasure-verses. A few such

verses are recorded here; Elminster assures me that as far as he knows,

no one

has yet found the treasures hinted at in

these examples. All of them await any

adventuring band that is strong and

brave, of keen wits and good luck. “That’s

why,” he added dryly, “they haven’t been

found yet.”