| YES | - | - | - | NO |

| Dragon 66 | - | - | - | Dragon |

YES.

SPELL-USERS SHOULD BE ABLE

TO USE "FORBIDDEN" WEAPONS —

BUT WITH DECREASED DAMAGE

BY JOHN SAPIENZA

NO.

RULE RESTRICTIONS

ON WEAPON USAGE

ARE FIRM AND FAIR

BY BRUCE HUMPHREY

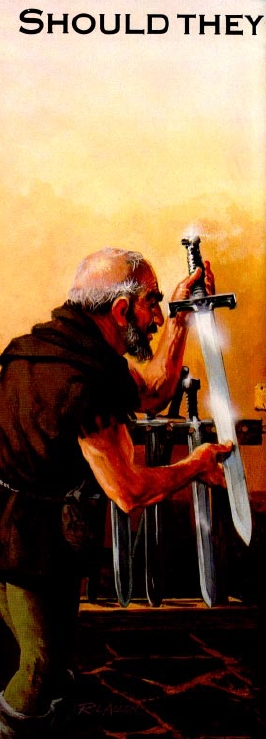

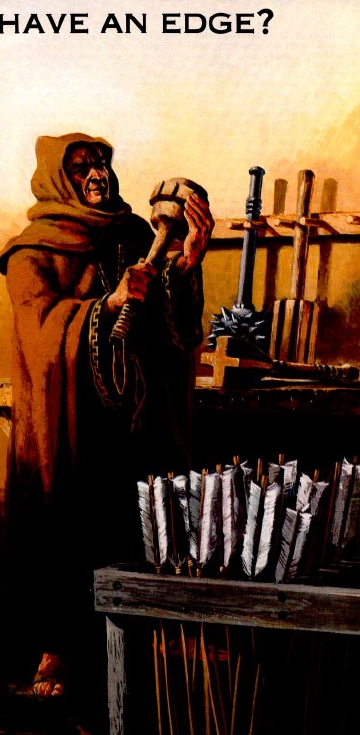

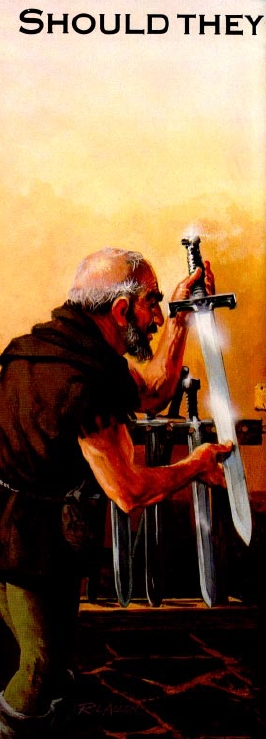

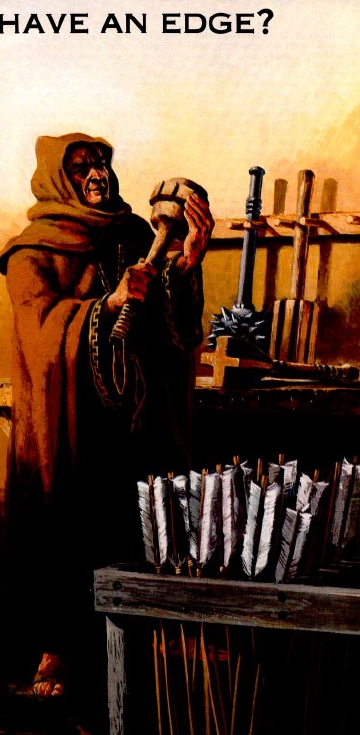

| The magic-user | - | - | - | The cleric |

YES

SPELL-USERS SHOULD BE ABLE

TO USE "FORBIDDEN" WEAPONS —

BUT WITH DECREASED DAMAGE

BY JOHN SAPIENZA

Every edition of the D&D® rules has distinguished between

the combat ability of various character classes by limiting the

weapons that could be used. The magic-user was limited to a

dagger as the weapon of last resort, the cleric was limited to

blunt weapons, while the fighter was allowed to use any weapon

desired but strongly encouraged to use the sword by virtue

of the fact that it has the best damage range on the weapons list.

In effect, mages were limited to d4 weapons, clerics to d6

weapons, and fighters steered toward d8 weapons.

In gaming terms, this makes perfectly good sense. Mages

have arcane powers and need to be limited in other areas to

keep them from dominating the game; fighters are weaponmasters

and need a system to express this; and the classes in

between need to be kept at a middling level of skill to favor

fighters in their specialty.

The problems arose on the role-playing side of the hobby, for

the rules dictated results without giving any explanation for the

reasons. There were even inconsistencies in the rules, such as

the existence for mages of +1 staffs, implying that mages could

use non-magical staffs as two-handed weapons as part of their

training because they had the skill to use the magical versions.

The worst problem was the limitation on clerics. The original

rules stated that the D&D game was open-ended as to societies

in which the DM set the campaign, with gods of any pantheon

available for clerics to follow. Yet the rules on clerics contained

many provisions that tied D&D clerics tightly to medieval

Christianity,

and in particular this included the rule limiting clerics to

blunt weapons. A mace was the proper weapon of a crusading

warrior-priest, perhaps, but this weapon choice made no sense

at all for a cleric whose god was always depicted in the temple

statuary with a sword or a spear — to use a different weapon

would be an affront to the cleric’s own deity. As a matter of

role-playing, the rule was a mistake, regardless of the gamebalance

goals that were the reason the rule was used.

There are also problems for fighters in the existing D&D

rules. In a tightly run, closed campaign, all the characters are

born in the area and grow up learning the weapons and armor

customary to the folk. But in most games, characters are drifters,

often from far lands and with strange garb, gear, and beliefs.

It makes poor role-playing sense to have every fighter

marching in lockstep with every other because the game rules

make one weapon the only sensible thing to use — yet that is

what happens in a D&D game. Only a hardened role-player

is

going to use anything but a sword, when the rules make the

sword the only single-handed d8 weapon on the list, most

others being d6 weapons regardless of description.

The wargaming considerations that guided the drafting of

the D&D rules have run roughshod over role-playing considerations,

it seems to me. One’s character’s choice of weapons

ought to depend on background cultural influences, including

racial preferences, as well as professional ones. I think it is

desirable to change the rules to encourage greater diversity of

choice — but how to achieve this while still keeping the different

character classes from becoming equal in terms of typical

damage done with their weapons of choice?

The solution to this might be to re-examine the rules on

weapon damage. This is a touchy subject, on which many

people consider themselves experts. Since I know perfectly

well that I am not an expert on this, I offer the following

suggestion

with some diffidence.

It seems to me that perhaps weapons cannot be defined with

great precision as to what damage they do, so what we really

are talking about is distinctions between weapon groups by

size and mass, rather than by shape and operation. I would

therefore not have one d8 weapon, a lot of d6 weapons, and a

few d4 weapons. Instead, I would change it to a lot of weapons

which in the hands of experts will do d8 damage, a smaller lot of

weapons that in the hands of experts will do d6 damage, and a

very few d4 weapons. The distinction in the new system would

not be by weapons, but by degree of training of the users.

The character classes in the D&D rules are divided basically

into fighters who are expert warriors, magic-users who are

completely incompetent in melee (at least in theory), and a

bunch of other types in between. In other words, D&D characters

fall into fighters, semi-fighters, and non-fighters in terms of

role models. Why not align weapon damage accordingly? An

expert would be able to get full potential damage out of a

weapon, a person given limited training with arms would be

able to get lesser damage, while a person untrained with weapons

would be able to get only a bare minimum from an unfamiliar

tool picked up in a panicked, last-hope defense.

Single-handed weapons would almost always do d8 damage

in the hands of a fighter, the master of weapons. This includes

the broad sword, battle axe, mace, war hammer, etc., and would

apply to fighters of most humanoid races allowed in the game,

which (depending on which edition of the D&D rules you are

using) includes humans, elves, and dwarves. Smaller creatures

such as halflings would be limited to smaller weapons in a

middle category, such as the gladius short sword. So would

full-size folk in unusual circumstances, such as an officer

forced to use a dress sword unexpectedly; these would do d6 in

the hands of experts. Thieves, who are limited to light, easily

concealed weapons because of the nature of their activities,

would use d6 weapons also, while as a mixed class they would

be limited to d6 damage even if using heavier weapons. The

same is true of clerics — a cleric with a broad sword would do

d6 damage. The reason for this is that, because they spend only

part of their time perfecting their combat skills, they cannot get

as much damage capability out of a weapon as a true expert

could. A magic-user or other non-fighting class would do only

d4 damage with unfamiliar weapons picked up, including that

broad sword, again due to lack of skill. Because the mage

spends all of his or her time locked up with arcane grimoires

learning new spells, there is no time for someone of this profession

to acquire the skill needed to do better than this. So, that d4

dagger is as good as can be had, and a lot easier to carry, too.

Because this is a weapons expertise system, the lack-of-skill

rationale could be applied to any character, regardless of class,

who picks up a totally unfamiliar weapon. That is to say, you

could promote role-playing by forcing players to choose what

weapons a character will specialize in, with four weapons for

fighters, three for semi-fighters, and two for non-fighters

(dagger and staff for mages as their single-handed and doublehanded

weapons — and no throwing daggers, that’s a separate

skill!). Attempting to learn a new weapon would have the character

(if a fighter) doing d6 damage for one level of experience

before getting it up to d8 expertise, while a semi-fighter would

do d4 damage for one level of experience before getting up to

d6 with the new weapon. Mages don’t go around learning new

weapons, and should be told so firmly. The same applies to

clerics and other semi-fighters who ask for more training to

improve their damage up to fighter level — they don’t have time

enough to improve that much.

This system, admittedly, bunches all weapons pretty much

into two categories, single-handed weapons of d8 and doublehanded

weapons of d12 maximum damage. I put the twohanded

weapons two dice sizes up for fighters to make up for

the significant loss in armor protection that not being able to

use a good magic shield can bring (but would limit mages to d6

damage with staff anyway). For those of you who feel that

weapons need to be more differentiated, you can always do that

by using a weapons vs. armor system. The point to using this

system is that it allows greater freedom in role-playing by making

weapons choice one of cultural and religious considerations,

while maintaining game balance.

WEAPON DAMAGE TABLE

------> Character Category

| Weapon Category | Fighters | Semi-fighters | Non-fighters |

| One-handed weapons | - | - | - |

| Battle axe | d8 | d6 | d4 |

| Broad sword | d8 | d6 | d4 |

| Dagger | d4 | d4 | d4 |

| Halfling weapons | d6 | d4 | -- |

| Rapier | d6 | d4 | d4 |

| Short sword | d6 | d4 | d4 |

| Spear | d8 | d6 | d4 |

| Thor's hammer (sledgehammer) | d8 | d6 | d4 |

| War hammer (war pick) | d8 | d6 | d4 |

| - | - | - | - |

| Two-handed weapons | - | - | - |

| Great axe | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Great hammer (military sledge) | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Great mace (maul) | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Great sword | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Halfling weapons | d10 | d6 | - |

| Hand-and-a-half sword | d10 | d8 | d4 |

| Lance (heavy spear) | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Lucerne hammer (military pick) | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Pole arms (halberd, pike, etc.) | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Quarterstaff | d12 | d8 | d4 |

| Staff, light | d10 | d6 | d6 |

| - | - | - | - |

| Throwing weapons | - | - | - |

| Throwing axe (tomahawk) | d6 | d4 | - |

| Throwing hammer | d6 | d4 | - |

| Throwing knife | d4 | d4 | - |

| Throwing spear (javelin) | d6 | d4 | - |

| Missile weapons | Rate of fire | Fighters | Semi-fighters | Non-fighters |

| Bow, long | 1/rd | d10 | d8 | - |

| Bow, short | 1/rd | d8 | d6 | - |

| Crossbow, light | 1/2rd | d10+1 | d8+1 | - |

| Crossbow, medium | 1/4rd | 2d6+2 | d10+2 | - |

| Crossbow, heavy (arbalest) | 1/6rd | 2d8+3 | d12+3 | - |

| Sling, hand | 1/rd | d8 | d6 | - |

| Sling, staff | 1/2rd | d10 | d8 | - |

“Semi-fighters” includes human clerics, druids, thieves, and

bards, and all combined-class characters such as elven fightermagic

users.

“Non-fighters” includes magic-users and illusionists.

The light staff (same size as a magic staff) is the only two-handed

weapon for which a M-U can receive combat training.

Magic-users do not learn the specialized skill of throwing a

dagger, or any other throwing or missile weapon. This is intentionally

restrictive, and should be strictly enforced if you want

to keep magic-users away from military skills. The throwing

weapons are all specialized weapons that are smaller than their

regular melee equivalents, hence the reduced damage.

The crossbow actually takes more time to use than shown,

but the figures given are workable. Since it is a lot easier to use a

crossbow accurately because you don’t struggle to hold the

string taut while aiming, I have made them +1 to hit for light, +2

to hit for medium, and +3 to hit for heavy crossbows, and this is

reflected in the damage figures. This benefit offsets the woefully

long time between shots. Hand-drawn bows really ought

to be given higher damage figures for realism, but given that the

archer gets in two to six times as many attacks as the crossbow

user, it seems better (for the sake of balance) to rate them as

shown for damage.

“. . . So I pick up the dropped sword,

and—”

“Wait a minute. You’re a magic-user,”

protests the DM. “You can’t use a sword.”

“Yeah? Why not?”

“I’ve been meaning to ask you the

same thing,” says a cleric, reaching for a

pike.

“But it’s in the rules,” is the DM’s only

plea to the mutinous pair.

The AD&D™ rules preventing magicusers

and clerics from employing certain

weapons often cause scenes like this.

The rules are necessary for play balance,

yet this is not enough for many players:

these rules should also be justified in

“logical” terms. And the DM should have

some effective (and consistent) recourse

when these rules are broken. Arguments

about Gandalf and Odin-worshipping

clerics carrying spears can destroy an

adventure, or at least the playing session,

so the importance of this topic

should not be undervalued.

The magic-user

What makes a magic-user tick? Judging

from the rules, the average mage has

excellent concentration, exercises precision

in what he does, a firm belief in the

success of his spells, and the calmness

necessary to bring about this success.

All these qualities are essential if he is to

“impress” spells on his mind, repeat the

words and movements exactly, and know

they will work. Being attacked while he is

casting a spell will negate the magic,

either because it breaks his concentration

or upsets the calmness he must

maintain. A nervous sorcerer, with doubts

about the efficacy of his spells, will not

be a sorcerer for long.

It has been suggested that it is not only

nervousness and lack of concentration,

but large quantities of metal, which upset

the delicate balances in a magic spell.

Many DMs of my acquaintance claim

that this factor alone would explain why

magic-users may not use weapons. In

part, this may be correct. A large amount

of metal (usually estimated at over twelve

ounces, or larger than the size of a

dagger) will tend to disrupt a spell unless

it is part of the material component of the

spell itself.

This would account for the “dagger

only” rule, but not for the prohibition

against using javelins, spears, or bows

(all of which have small metal heads, or

heads which are comfortably far from

the user’s body), nor with using all-wood

or bone-tipped spears (not a great alternative,

but seemingly viable for a creative

player). Using this loophole in the

“metal rule,” a creative group might try

snaring a strong magician with a metalbraided

rope, or throwing a metal shield

at him, in hopes of neutralizing his magical

talents.

Nor are all types of armor included in

this rationale, since leather and padded

armor can theoretically be made without

utilizing enough metal to bother the

spell-caster wearer. Because of these

difficulties, the “metal rule” is not a universal

enough reason for magic-users to

avoid using weapons.

Because of the nature of the magic-user’s

mental makeup, there are several

psychological reasons which can be advanced

for the weapon restrictions on

magic-users. Because these “psychological

reasons” are in the caster’s mind,

they remain with him at all times, and

cannot be voided without eliminating his

usefulness in magic as well. Since magic

use is a taught skill, the limitations are

passed on from teacher to pupil, accounting

for the all-encompassing and

continuing aspects of these restrictions.

The main reason magic-users can’t

wear armor is the inhibiting characteristics

of this form of defense. To cast

spells, the magic-user must be relatively

free to move — and this involves not just

physical freedom, but psychic freedom as

well. A mage in armor feels as constrained

as if he were physically tied up.

The very act of spell casting is a claim for

total freedom, for the mage is reaching

out to another place, free from the restrictions

of other men. For such a person

to be constantly (or even temporarily)

wearing armor — which reduces

freedom — is absurd. Robes and cloaks,

the traditional garb of magic-users, are

loose and free-flowing clothes, which

perhaps don’t enhance the “bid for freedom”

but certainly don’t work against it.

There is a symbolic aspect to the wearing

of armor as well, one which would

inhibit the magic-user’s subconscious.

Body armor symbolizes primary concern

for the physical world, framing the mindset

for fighting and other bodily concerns.

The profession of the magic-user

is concerned with the world of the mind,

and the continued wearing of such protection

would draw his thoughts away

from his spells toward more concrete

concerns, no matter how dedicated his

original plans were.

The weapon prohibitions are also

bound to symbolism. The tools of combat

and the thought mode for their use

are the antithesis of the skills and

thoughts used in magic, and so are pro-

foundly disturbing to magic-users. This

also explains the natural antipathy between

fighters and mages. The use of

such potent, purely physical, modes of

combat symbolizes, for the magic-user,

the forsaking of magic and the acceptance

of the fighter’s world and values.

The use of any weapon, other than the

obviously defensive dagger and quarterstaff

(these may also be justified, in the

M-U’s subconscious, as tools useful for

more than just fighting), contradicts the

mind-set of the magic-user, turning him

into a weak and untrained fighter. The

armor justification is tied in to this, in

that wearing armor admits the weakness

of the magic-user’s own spells and the

need for such protection. His decision to

wear armor, or use prohibited weapons,

introduces the fear of failure into the

M-U’s, psyche, making any subsequent

attempt at magic useless.

What happens to a magic-user who

uses a prohibited weapon or wears armor?

The first occurrence results in the

loss of all the rest of his spells for that

day. He cannot use spells again at all

until he spends a 24-hour period in contemplation.

For more severe “first offenses,”

the M-U may be required to forfeit

10% of his experience points, and/or

be beset with one form of insanity for a

period of weeks equal to 20 minus the

M-U’s wisdom score.

The second time a

magic-user so assaults his own sensibilities

results in his losing all spell-casting

abilities. One use of a prohibited weapon

or armor means the use of such an item

in one combat encounter, for the duration

of that (single) battle, no matter how

many rounds it lasts.

Like the magic-user, the cleric has

certain

psychological requirements to be

met for the successful casting of his

spells. Primary is the feeling of holiness,

the sense of being in touch with his deity.

Factors in this are calmness, thoughts

pleasing to the god, and self-assurance.

The cleric must have no doubts as to his

personal worthiness to act as the tool of

his god. These are the thoughts which

affect the cleric’s choice of weapons.

The cleric seems to be modeled on the

medieval priest, who was (officially) forbidden

to use weapons which purposely

spilled blood. But it has been contended

(primarily by players of cleric characters)

that certain gods who use sacred

weapons would promote the use of similar

weapons by their priests, either for

identification, or for a feeling of kinship

with the god. The ban on the use of weapons

other than the “smashing” type can

be justified, however, and this justification

especially applies to chaotics and

evil types, who would be the first to object

to the rule.

Blood is the primary reason for the

restriction, not because of a ban on the

spilling of blood, but rather because of

the presence of the element itself. Holy

thoughts and feelings of closeness to a

deity are not easily mixed with violent

death and spurting blood. An evil cleric

would quickly lose his calm facade, becoming

enamored with the idea of hacking

and murder. A neutral would find it

distasteful to contact the fluid, and good

types would find it positively abhorrent.

These all pertain primarily to combat,

not to the holy spilling of blood, which

involves a cleansing ritual and certain

selfless feelings. Unless it is “purified,”

blood disrupts the sacred thoughts flowing

through a cleric’s mind, and the mind

would later continue to dwell on the

memory of the sight. Any religion which

specifically promotes the spilling of

blood only does so in certain prescribed

rituals, not in the haphazard way of

combat. Spilling blood for a deity becomes

almost sacrilegious if done outside

of such a ritual. (At least for a cleric,

such a ritual would not include wading

into battle while yelling, “Blood for my

Lord Arioch!“)

Additionally, players must remember

that the main goal of any religion is to

gain converts. There is also the matter of

punishing the wicked (usually in the

course of requiring their repentance).

Maces and club-type weapons are well

suited for both punishment and conversion

(while making certain that the convert’s

skin stays whole), without being

necessarily “killing” instruments. The

mere presence of such tools reminds the

cleric of his duty to his god and his duty

to convert sinners and unbelievers, causing

him to feel closer to attaining his

ultimate goal.

In a similar vein is the symbolism behind

the mace and other club-type weapons,

which comes to the fore in the

hands of a cleric. Staff-like weapons portray

the cleric’s role in divine matters

much as the rod (similar in form) is a

symbol of kingship. Clerics are taught

this connection and it becomes deeply

ingrained in their minds. A union between

the weapon he uses and his right

to perform the holy spells of his office is

formed in the cleric’s mind. His weapon

promotes his feeling of sanctity.

The combination of the cleric’s psychological

need for a certain weapon

and the disquiet involving impure bloodletting

sets certain restrictions on the

clerical mind.

Should a cleric take up a

pointed or edged weapon and use it, the

effects are devastating. His feeling of

impurity will prevent him from using any

clerical spells until a cleric at least three

levels higher casts a Bless spell on him.

In any case, he will lose 10% of his experience

points and will (wisdom times five

percent of the time) feel the need to go

on a holy quest or a pilgrimage.

The second

time he commits this transgression,

he loses his clerical powers altogether,

usually becoming the equivalent of a

first-level fighter.

OUT ON A LIMB

‘The nature of faith’

Dear Editor:

I enjoyed seeing my article on the use of

weapons of choice in DRAGON #66 printed

with a rebutting article by Bruce Humphrey,

defending the rules limiting certain character

classes to specific weapons. Bruce’s approach

concerning magic-users and his suggested

psychological aversion to using physical

weapons and defenses being an essential part

of the mindset required to cast magic spells

was interesting. It’s certainly as valid an excuse

for the rules as any I’ve seen, if you can

talk your players into seeing it that way. The

opposite approach is the gamer who plays his

MU as wearing daggers stuffed into his boots,

belt, and backpack in profusion, with protection

rings and spells letting him jump into

melee!

I strongly disagree with Bruce concerning

clerics, however. Here we part company on

the very nature of religious faith. It seems to

me that Bruce insists on transferring the

Christian aversion to the shedding of blood to

the priests of all pagan deities. He argues that

even less-than-good deities would limit their

clerics from spilling blood in other than ritual

grounds and temples. The problem with this

is that it ignores the gods of war. Granted that

most religions that required blood sacrifice,

including human sacrifice, did so for the most

part at the altar or sacred grove in ritual conditions.

But the logical place for a sacrifice to a

god of war is on the battlefield, and a study of

history yields a number of instances in which

societies were formed around this concept.

The most extreme example of this was the

war god of the Aztecs. Most primitive early

cultures had fertility or nature deities to whom

blood sacrifices were offered every year to

insure the end of winter and the blossoming

of crops to maintain the life of the tribe. The

Aztecs carried this idea to extremes; unlike

the early Greeks, who only made sacrifices

once a year, the Aztecs went to war with

neighboring tribes to feed the earth with

blood in honor of the gods.

The most extreme example of this was the

war god of the Aztecs. Most primitive early

cultures had fertility or nature deities to whom

blood sacrifices were offered every year to

insure the end of winter and the blossoming

of crops to maintain the life of the tribe. The

Aztecs carried this idea to extremes; unlike

the early Greeks, who only made sacrifices

once a year, the Aztecs went to war with

neighboring tribes to feed the earth with

blood in honor of the gods.

I’d like to avoid pointless arguments over

the different standards appropriate to different

gods in each section of the AD&D ninefold

alignment system. Whether or not shedding

blood seems “good” or “neutral” or “evil”

to you is beside the point in discussing the

weapons that would be selected by the clerics

of a specific god. If a god uses weapons at all,

and at least half of the gods are so described,

then it logically follows that the worshipers of

that god will use the same weapons for the

same purpose their patron deity does, in

furtherance of his commands. If a cleric is a

follower of a war god, he is going to regard

spilling blood as an inherent part of his duties

— and a mere incident to the main activity,

which is killing enemies.

The argument that the mace is a symbol of

authority because it resembles the rod or

sceptre is also spurious. In a world in which

the gods are real, and can be called upon for

aid, the symbol of authority carried by a priest

of a specific god will be the kind of thing that

characterizes the god’s function in the universe.

A god is generally symbolized by one

specific thing, such as the bow for Diana, the

spear for Odin, and so forth. A weapon

is of

itself a symbol of authority, and a priest who

carries his god’s favorite weapon is a symbol

of the authority of the god himself, who

stands behind the priest and gives him his

power and station in society. Therefore, it is

hard to believe that a priest of a warlike god

would ever feel comfortable without that

weapon, specific to his patron god, either in

hand or within easy reach.

This is at least the second time such arguments

have appeared in DRAGON, but they

are just as culture-blind today as in the past.

The problem with this approach to rationalizing

rules is that it ignores the society the

character lives in, the religion the character

believes in, and the fundamental role-playing

assumptions that go into creating a character

who is a cleric of a pagan deity. Instead, we

get a warmed-over and disguised version of

Christianity poured into the wrong molds. To

which I respond: Nonsense. Play a medieval

Christian warrior-priest under the mace-limit,

but don’t try to force that rule on my priest of

Odin, because when you do so the game

ceases to be a role-playing activity in any

meaningful sense. May I suggest a study of

history as a source of role models?

John T. Sapienza, Jr.

Washington, D. C.

(Dragon #68)