The danger of player boredom is one to

concern every DM. No matter how good

your dungeon is, there can come a point

when your players find it uncomfortably

familiar. In previous issues, DRAGON®

Magazine has offered many answers to the

problem, from new treasures and monsters

to tips for better refereeing. This article

offers one more answer ? the use in

AD&D® gaming of parallel worlds.

A short

hop to a strange land can do wonders in

removing campaign ennui.

The parallel-worlds concept is a classic

idea in science-fiction and fantasy literature.

It states that an infinite number of universes

are in existence, independent of each other,

separated by extradimensional barriers of

time and space. In fantasy, it has been the

basis for DeCamp and Pratt's Harold Shea

books, Randall Garrett's Lord Darcy sto-

ries, and various novels by Poul Anderson

and Michael Moorcock. (This is by no

means a complete list.) The official AD&D

material has very little to say about the

concept (except for the superb use of paral-

lel worlds in the Queen of the Demonweb

Pits module), but they can

add a lot to the

game. By leaving the worlds of ?normal?

AD&D gaming behind, the DM?s options

are expanded ? new environments, new

creatures, new forms of spell-casting, and

other surprises can be introduced to con-

found and intrigue your players.

Caer Sidi

Types of parallel worlds

To begin with, where do these alternate

worlds tit in the orthodox AD&D universe?

<revise: Deities && Demigods>

<revise: Manual of the Planes>

The answer, according to Legends & Lore,

is that the Prime Material Plane

encom-

passes the real world and all of its paral-

lels.-- I don?t think it violates the spirit of

the game, however, to suggest that there

may be other worlds existing outside the

Prime Material Plane on other, different

levels ? Alternate Material Planes, let?s

say. The difference could be that the powers

of the gods and the laws of nature will be

more or less consistent from world to world

within a given Material Plane, but there

could be great differences between that

Material Plane and any of its Alternates.

The might of the gods themselves could

change (more on this later) and ?reality?

might be very different from ordinary

AD&D worlds. While this is not a

license

for completely overthrowing the game, it

can justify some of the variant world-

concepts discussed further on.

The Frozen Lands

Whichever plane your parallel world

inhabits, there still remains the task of

building it and making it distinct and differ-

ent from the one used in the current cam-

paign. The world may be physically similar

to your old one, with the difference lying in

the monsters or magic it contains, or it may

have physical conditions unlike the ones

your characters are accustomed to seeing.

Maldev

For example, instead of a round parallel

world, how about a flat one? I use a flat

earth for my campaign, because of my own

desire to try something different. The most

obvious change, from the viewpoint of

someone from a round world, is that the

horizon extends to infinity; given an unob-

structed view, it?s possible to see much

further than on our own planet. Because

there is no earth-curvature, everything is

more or less the same distance from the sun

(which, in this universe, goes around the

earth). No polar or tropical regions exist,

and there are no changes in seasons ? a

perpetual temperate spring reigns through-

out the world. Bear in mind, however, that

spring in the American Midwest can in-

clude anything from summer heat waves to

winter blizzards; the weather isn't boring.

Differences in climate are caused entirely by

features of the land -- the center section of

my northern continent, for example, is

bounded by mountains on both sides, shut-

ting off the rain and creating a desert.

Lolth's Prison

All this, in turn, creates changes in hu-

man life. Consider farming: Instead of

having separate times of the year for grow-

ing and harvesting, farmers can plant and

reap year-round. Because of the erratic

weather, however, it?s more important for

the plants to be tough and durable than big

? in other words, they can grow more

plants, but smaller ones. Because there are

no seasons, the only measure for the calen-

dar is the moon, which waxes and wanes

like our own (but in relation to the power of

the moon goddess, not the angle of the sun?s

light). The moon?s cycle of exactly twenty-

eight days makes one four-week month;

fourteen months make a lesser year and two

such years ? twenty-eight months ? make

a Great Year (all of which makes it a heck of

a lot easier to keep track of days and dates).

The result is a distinctly different world,

with the differences evolving logically from

the basic decision to make it flat.

Some people may be bothered by the fact

that a flat earth isn?t scientifically feasible

(there seem to be a lot of arguments along

those grounds in "Forum" sometimes).

Personally, I don?t think feasibility matters

in the slightest. In fantasy, as Fritz Leiber

once put it, it?s not necessary to be reality-

consistent, only self-consistent. In other

words, it doesn?t matter if your new world

is ?impossible,? in the sense that it contra-

dicts the laws of nature, provided that its

own laws don?t contradict each other.

Another possible shape for a new world

would be an elliptical one. Because the

atmosphere of any world, no matter what

shape, will take on spherical form, the ends

of the ellipse, poking out of the sphere, will

have very little atmosphere ? or possibly

none at all, if the ellipse is extreme enough.

Either way, survival at the ends would be

difficult or impossible without magical

protection. It?s also possible the world

would wobble on its axis as it rotates, so

that the length of the days and seasons

would vary wildly ? some years might have

no winter, while other years could have

triple-length ones.

What if a world had two suns? The planet

could orbit one of the pair or both of them

at once, but physics dictates that it cannot

orbit one and then the other. Then again, a

flat earth doesn?t fit in with physics, either.

In an AD&D campaign, it?s possible

that

the local deities provided some powerful

artifact to protect a sun-changing world

from harm as it went through its climatic

alterations. If the local evil arch-mage were

threatening to destroy the artifact, that

would certainly be a challenge for the player

characters to deal with.

A world could be shaped like Burroughs's

Pellucidar, located on the inside of the

Earth, so that the horizon curves up in the

distance. One could pick an even stranger

shape, like Larry Niven's sun-circling

Ringworld, or the ziggurat-shaped planet in

Philip Jose Farmer's The Maker of Uni-

verses. Even on a spherical world, there

could be unexpected differences -- every-

thing could be a hundred times its normal

size, for example, so that the characters

appeared no bigger than rats. Suppose the

surface of the planet was airless, confining

all life to caverns and tunnels below the

ground, or it was unstable, with volcanoes

and earthquakes a part of daily life. What of

a planet covered by an ocean and small

islands, like LeGuin's Earthsea-- I think

you?ve got the picture.

Populating a parallel world

Once you?ve settled on the world you

want, the next step is to populate it. A new

world allows you to introduce an assortment

of variant monsters to surprise your players.

One simple but effective step is to reverse

alignments, presenting players with evil

unicorns and treants, and good fire giants

and werewolves. Monster powers should be

adjusted accordingly ? an evil unicorn?s

horn being poisonous rather than a poison

antidote, for example. A second possibility

would be to give more kinds of magical

powers to creatures, creating gnoll illusion-

ists and giant magic-users. One could go

even further and allow one or more of the

demi-human or humanoid races to have the

same range of classes and-lack of level re-

strictions as humans ? halfling arch-mages

would be pretty surprising, while a few half-

orc assassin/magic-users could be both

surprising and nasty.

For an even more alien world, this can be

taken even further. What if the race domi-

nating the new world ? in the sense of

having no class or level restrictions ? were

neither human, humanoid, or demi-

human? What if evolution had turned out

differently and the ruling race had evolved

from dogs, cats, birds, fish, insects, lizards,

or spiders? What would their society be

like? How would they react to humans?

Would elves and dwarves exist, or would

they be replaced, too? For example, cat-

people could fill the place of humanity,

while bird-, lizard-, and dog-people fill the

roles of races with limited classes and levels.

The AD&D game already has intelligent

forms of most kinds of animals, so it?s not

that great a jump for them to reach full

"human" status.

A different physical world will also pro-

duce different inhabitants. If your world is

an Earthsea-style world, adapt land-going

monsters for the ocean; the two Monster

Manuals have already presented sea-going

forms of elves, ogres, gargoyles, and ghouls,

and you can add to the list. Could there be

sea-dwarves or sea-gnomes to match sea-

elves? How about aquatic sphinxes, mino-

taurs, medusas, or puddings? Whatever

your new earth is like, see if there are ways

old monsters could adapt to it.

Once your world is built and populated,

you can civilize its inhabitants. Even if the

people of your new realm are humans and

demi-humans, you can still give the world

special qualities through their cultures. For

example, what if the world is in a more

advanced era than the usual setting? It

would be a novel experience for most play-

ers to find their characters in societies like

Elizabethan or Victorian England, or

France during the revolution. Coping with

new customs and a different class structure

would be challenging. (The Victorian class

system was, if anything, harsher than that

of medieval times, while the French Revolu-

tion sought to dispense with the aristocracy

completely.)

A culture could be developed that has no

connection at all with Earth history. Sup-

pose that the new world had once reached a

peak in science and technology and then

deteriorated; its ?magicians? now combine

real magic with advanced science. (The

Thundarr TV cartoon series used this con-

cept extensively.) This would allow use of

many new forms of techno-magic, such as

robots, lasers, holograms, and so on.

On Dragonworld, dragons taught witch-

doctors and magic-users their spells and

offered to protect tribes and towns against

the rest of the world ? in return, of course,

for food, shelter, and lots of treasure. Today,

every village, town, and tribe has its own

dragon, of variable age, power (the stronger

the city, the older and more powerful the

dragon), and appropriate alignment (brass

dragons with elves or chaotic good humans,

black dragons with chaotic evil men or

gnolls). The dragons receive food and trea-

sure from their allies and, in return, protect

them in time of war. (If it looks like its meal

ticket is going to be wiped out, a dragon

will do whatever it takes to protect the

gravy train.) Not everyone believes this

benefits humans as much as it does dragons

? but no one wants to be without a dragon

protector, nonetheless.

All this has made Dragonworld different

from my primary campaign world. Where

my regular game world has only a few

varieties of dragons (mostly those

from the

Monster Manual), Dragonworld has them

all. All the official species and many of the

unofficial ones (like the neutral crystalline

dragons, the yellow,

orange,

and purple

dragons, and the landragons

from

DRAGON issues #37, #74, and #65, re-

spectively) exist, for every species has a

good chance to survive and breed. Simi-

larly, while most of the humanoid species

have been wiped out on my earth (only

goblins and gnolls exist in large numbers),

almost all races survive on Dragonworld

under their lizardly protectors. Where the

regular campaign world has been domi-

nated by a succession of empires, Dra-

gonworld has become the province of

innumerable independent city-states and

tribes; conquest by the sword has, of neces-

sity, been superseded by political and eco-

nomic pressure and Byzantine intrigue.

In some ways, even the basic outlook is

different. A human from my main world

would be totally confounded by the affection

most Dragonworlders have for dragons,

while a Dragonworlder would be equally

bewildered by the idea of subduing a

dragon, let alone selling one. It?s in these

ways that parallel worlds can be built and

differentiated.

Magical variations

Even after your world is built, populated,

and civilized, still more can be done to

make it unusual. One way to give your

players some new experiences is to intro-

duce variations in the way magic works.

Suppose that boundaries between your

new world and the Positive and Negative

Material Planes are weaker or stronger than

in most worlds. This could affect the

amount of energy drawn from the planes by

spells and magic items, so that they would

only have one-half or one-third of their

normal power (where the barriers were

stronger) or be increased to double or triple

force (if weaker barriers existed). With

lessened magic, PCs would find adventur-

ing far more difficult (and more challeng-

ing); enhanced magic could be a lot of fun

for a short while, like giving players high-

level characters to run for one adventure.

Of course, if they were going to be in an

enhanced-magic world for some time, game

balance might dictate pitting them against

equally enhanced opponents ? like double-

strength ogre magi.

A second possibility is that power from

the energy planes seeps constantly into the

new world (instead of being drawn there

only by spells). As a side effect, the natives

could have built up ?immunity? to the

magical energy ? in other words, even the

weakest of creatures have developed some

degree of magic resistance.

It?s also possible that a different world

will have new, different spells. In the

?Earthsea? world described earlier, druid

spell lists might be expanded to include

predict tide, summon current, and call sea-

being. Magic-users and clerics would also

have new spells, along the lines of create

whirlpool, tidal wave, or neutralize drown-

ing, and might have spells such as water

walking or water breathing at 1st or 2nd

level. If the DM allows PCs to learn a

lower-level version of a regular spell like

water breathing, it might be wise to reduce

the power and duration to make it fit a 1st-

level listing.

Another possibility is that the magic-users

in your new world are not generalists, as

they are in regular AD&D gaming,

but

specialists. In this case, fire magicians, ice

magicians, healers, shapechangers, and so

on make their appearance, perhaps grouped

into colleges or guilds like the spell-casters

of the DRAGONQUEST game. This can

be fixed by regrouping AD&D spells

along

guild lines; thus, a fire magician would

know not only burning hands, fire shield,

and fireball, but non-magic-user spells like

produce flame, flame scimitar, fire strike,

and fire resistance, with most of them avail-

able at lower levels than a character would

get them (for example, getting a 1d6, small-

area fireball at first level).

Consider the confusion when a wizard

like that meets an orthodox AD&D

en-

chanter. To the fire-wizard, the latter will

seem like some super-spell-caster, capable of

using spells from every college; a conven-

tional magic-user, on the other hand, will

assume someone who flings around walls of

fire and flame strikes is a much higher-level

character than he actually is. This could

lead to some intriguing situations.

It?s also possible to make some simple

alterations in the spells themselves. Under

the natural laws of the new universe, cast-

ing time might be altered, different material

components required, or spell duration

prolonged or shortened. Perhaps there?s a

particular material component essential to

all magic-user spells, the way druids are

dependent on mistletoe. Changes like these

could bewilder and surprise the spell-casters

in your party, in some cases making them

virtually powerless until they learn how the

new rules work.

Suppose there is one kind of magic ?

enchantment/charm spells, illusions, poly-

morph spells, or weather-control magic ?

that simply doesn?t work in the new world.

Perhaps, at some time in the long-gone

past, a foolishly arrogant magic-user at-

tempted to charm one of the gods; as a

result, the outraged deity declared the use

of such spells forbidden for all time. If a

character casts one, it might simply fail, the

caster might fall under the spell himself, or

some other penalty you deem appropriate

might take effect. Nor need the classifica-

tion of taboo spells be as simple as ?charm

spells? or ?illusions?; it can be based on

any rationale you wish. For example, the

gods could ban any spell of magic item that

does damage outside the range of hand-to-

hand combat. In order to attack someone,

you have to get close enough to him to risk

being hurt yourself.

Finally, what about a world where every-

one ? not just clerics and magic-users ?

can cast spells. Perhaps everyone is capable

of learning magic-user cantrips (which are

some of the most useful spells in non-

combat situations) or casting at least one

particular useful spell ? cure light wounds

or enchanted weapon being common knowl-

edge, for instance. Alternatively, everyone

might possess one unique spell of his own,

like the inhabitants of Piers Anthony?s

Xanth ? one has magic missile, another

can haste himself, while a third can purify

food and drink. In either case, near-

universal use of magic could make a fight

with even zero-level characters hazardous.

It would not be advisable to let player char-

acters learn these special spells. At the very

least, the DM should have PCs forget them

when they return to their own world.

Variant psionics

Having touched on magic, let?s consider

a closely allied topic ? psionics. Even if

your regular game doesn?t use them, creat-

ing parallel worlds that do could prove

intriguing for your players. For example,

some of the ideas given above for magic

could be reused for psionics ? everyone

native to that world could have one random

psionic ability, or they could all share one

common power, like ESP, teleportation, or

telepathy. Then again, perhaps only one

branch of humanity possesses special

powers ? a race possessing innate mass

domination, for instance, could become

master of its world.

A new world might also affect the player

characters, perhaps stimulating any latent

psionic talents they possessed. A character

who is potentially psionic (having charisma,

intelligence, or wisdom above 16) will be-

come psionic while on this world; but with-

out being in control or even aware of his

powers at first. Awareness might only come

when some condition is fulfilled; after a set

period of time, a developing talent might

start to function but randomly so, or there

could be a percentile chance of activating a

talent during moments of intense stress.

The latter would make the PCs? first battle

pretty bizarre ? imagine trying to fight

while talents like reduction, dimension door,

or etherealness were activating randomly!

Needless to say, game balance usually dic-

tates that the PCs lose these powers on their

return home.

The social implications of psionics should

also be kept in mind. How would a society

of telepaths react to a party of nontelepathic

characters? Would they mock them? Treat

them as little more than cattle? Subject

them to ?treatment? for repairing what

they assume are damaged telepathic facul-

ties? (What effects that could have would be

anyone?s guess.) Legality might be another

important factor; a world where psionics are

commonplace may have firm laws about

what is and is not permissible (no reading

minds without a warrant, no taking over

someone else?s mind, etc.). Violating these

rules would bring a great deal of trouble to

the PCs ? and this would probably apply

to spells like charm person and ESP, too.

Borrowed game worlds

These suggestions cover some of the

possibilities for creating an original parallel

world of your own. But there is another way

besides building your own to provide your

players with new and different earths, and

that is to ?borrow? your new world from

somebody else.

One means of doing this is to use another

gaming system as the basis for the alternate

world. The DMG discusses this on pp. 112-

114, working out the possibilities and

details

for sending AD&D characters into

a

GAMMA WORLD® or BOOT

HILL®

game. The appeal of this approach is natu-

ral ? the laws of nature and much of the

background for the new world are already

worked out for you, yet your PCs will still

be thrust into a-totally different setting

offering a variety of new adventures.

There?s no need to stop where the DMG

does ? you can use just about any gaming

system if you?ve a mind to. How about

setting adventurers loose in the Roaring

Twenties of the GANGBUSTERS? game?

Why not have them join forces with the

agents and spies of the TOP SECRET®

game? The heroes and criminals of FGU?s

VILLAINS & VIGILANTES? game?

(Perhaps some super-criminal is recruiting

evil magic-users for a sinister plan, driving

the heroes to seek the assistance of the

player characters.) One could also put them

into another magic-based game system, like

that of the DRAGONQUEST? game or

the RUNEQUEST® game.

Whichever system you pick, using it will

require the same sort of work the DMG did

for the GAMMA WORLD and BOOT

HILL games. If the new game uses a differ-

ent set of character abilities, one will have

to generate the statistics that the characters

don?t have. If the range of stats is different

(5-25 for normal humans, for instance,

instead of 3-18), the equivalent in the

AD&D system has to be calculated.

In

addition, one has to answer a dozen other

questions. How do you adapt characters to

a different initiative system? How do special

rules covering fatigue or critical hits apply

to the PCs? What are the effects of new

weapons or powers, such as machine-guns

or the V&V absorption ability, on AD&D

characters? If characters from other games

and worlds pass into an AD&D universe,

all

of the same questions must be asked in

reverse.

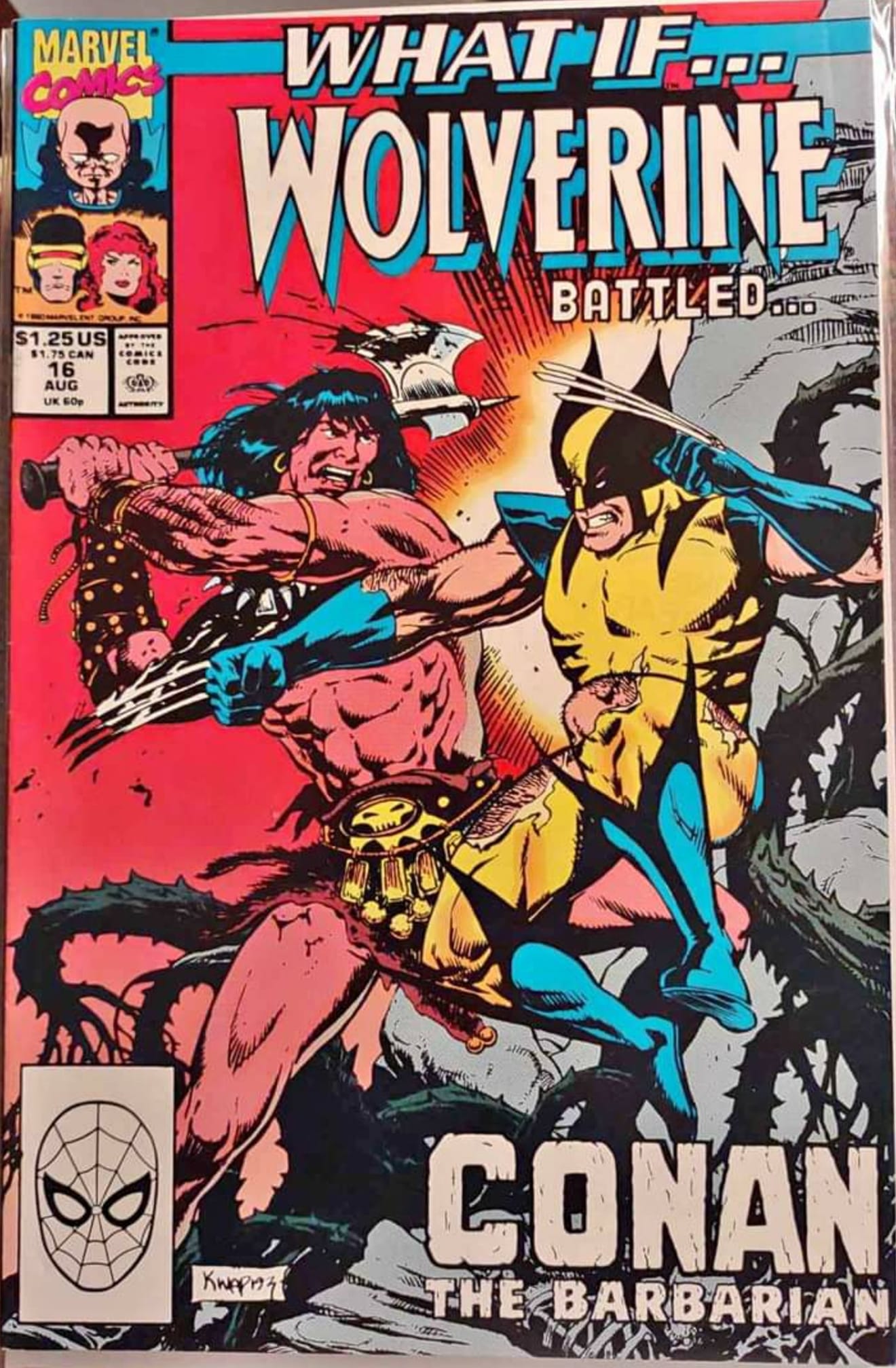

Borrowed fiction worlds

An alternative to borrowing an estab-

lished gaming system is to borrow an estab-

lished fictional system. Players who read

fantasy are bound to have favorite charac-

ters, be they Fafhrd, John Carter,

or

Conan; think of the pleasure your players

can find in visiting their favorite heroes in

their native worlds. For my taste, it?s best

that they be in their native worlds. Seeing

Elric without Melnibone or the Mouser

without Nehwon just wouldn?t seem right;

their worlds are part of their charm. Rather

than establishing these heroes in one?s own

world, where they can never really fit in,

one can use a parallel world system to let his

players meet whom they wish, going to

Covenant's Land or Amethyst's Gemworld

with no trouble.

Even more than an ordinary game, how-

ever, one using an established fantasy re-

quires preparation. To begin with, do you

know the mythos you?re using? It might be

fun to take your players? characters to Mid-

dle Earth, but it could be disastrous if they

all know Tolkien better than you; the odds

are they?ll catch every error you make in

handling their favorite work and scream

indignantly at all of them, which is hardly

conducive to an enjoyable evening. One

must also not only be familiar with the

personalities and histories of the characters

from the book but must translate their

powers and abilities into AD&D terms

?

what level magic-user is Glinda the Good,

for instance? There are many resources to

help out here ? Legends & Lore and many

articles in DRAGON Magazine have given

stats, powers, levels, and descriptions for

many fictional and legendary heroes.

Then too, how much change are you

willing for the PCs to bring to the estab-

lished course of events in the fiction-world?s

saga? If you have them enter Elric?s world

during the events of Elric of Melnibone,

for

example, suppose they revise the entire

Elric canon by killing Yrkoon? If you?re not

ready for that (and I can vouch from a

similar experience that it can be extremely

unsettling), it might be better to involve

them in a minor adventure that won?t affect

the major hero?s destiny.

[AD&D game adventures are available

for Conan's Hyboria (modules CB1 and

CB2) and Fafnrd's Nehwon (Lankhmar:

City of Adventure). Chaosium's Thieves'

World game setting described the famed city

of Sanctuary from the anthology series in

AD&D terms as well. -- Editor]

Character problems

Whether one uses an established alternate

world or an original one, and whatever

surprises the world contains, the same PCs

will visit it. Some player character classes

are going to have problems no matter which

world they go to. Of them all, clerics will be

the hardest hit, for they must deal with the

fact that residents of other worlds and Alter-

nate Planes may not worship the same gods.

This is entirely understandable (with an

infinite number of worlds, even the most

energetic deities can?t proselytize them all),

but it still gives clerics a problem. When

they enter a parallel world, it?s entirely

possible that no one there has even heard of

their gods. The native deities will probably

want to keep it that way; who needs the

competition? If clerics of the Greek gods

were to try preaching their creed on a world

ruled by the Celtic deities, they would

probably be ridiculed (?Zeus? Hephaestus?

Where?d you make up those names??) and

would certainly run into heavy opposition

from the established churches. At best,

they?d simply be forbidden to preach; at

worst, they?d be outlawed, condemned as

heretics, hunted by the church, and possibly

threatened with divine wrath as well.

It?s also unpleasantly feasible that on

some worlds the clerics will find their

powers diminished. According to Gary

Gygax (in an article in DRAGON issue

#97), the powers of the gods depend

on the

number of their worshipers on the

Prime

Material Plane; a deity without

such wor-

shipers ?is consigned to operations on some

other plane of existence, without the means

to touch upon the Prime Material.? Logi-

cally, this should also apply to Alternate

Material Planes ? if a god has no wor-

shipers there, he has no powers. Thus, if a

cleric arrives on a world in such a plane, his

god would be almost completely unable to

aid him and ? as happens on the planes of

Hell or the Abyss, where clerics are simi-

larly cut off ? the cleric would be unable to

recover any spells above 2nd level, since

anything higher draws upon the divine

power. Needless to say, this could prove a

dire situation.

Another possible problem (on a world in

any plane) is that the ruling deities are

active enemies of the cleric?s god. Imagine

the position of a good priest, for instance,

on a world where daemons and devils were

the greatest powers, or the danger to a

priestess of Athena on a world where her

arch-enemy Ares was the dominant deity.

Clerics could wind up making some uncon-

ventional alliances ? a lawful neutral cleric

might join forces with devils or rakshasa in

order to break the grip of demonkind on a

world where those chaotic beings held sway.

A cleric?s life definitely won?t be easy, but it

won?t be dull, either.

The other classes with problems will be

those with limited membership at high

levels ? assassins, druids, and monks.

There is only one 10th-level monk in a

campaign area, for example, so if a player

takes his own Master of the North Wind

into another world, he may soon be tagged

as an impostor or a fraud.

Maintaining the balance

No matter what you have planned in

your new world, it?s important not to over-

look game balance. With parallel worlds so

full of special surprises, there?s always the

risk the PCs will come into possession of

(From page 42)

something a little too special; the thought o

a character returning to his homeworld

bearing Stormbringer should be enough to

make any DM blanch.

The problem is hardly absurd; there was

the article in DRAGON issue

#82 citing

characters who?d acquired everything from

battlestars (as in Galactica) to Thor?s ham-

mer. One has to be as careful giving out

treasure on parallel worlds as he would be

in his primary campaign. While a reason-

able amount of caution should protect the

mightiest artifacts (it shouldn?t be very hard

to keep your PCs from getting

Stormbringer unless you actually want them

to get it ? in which case, you deserve the

results), it?s sometimes harder to make

decisions about low-powered ones.

This is particularly true on technologi-

cally oriented worlds; since most items will

not be found in the DMG, it may be diffi-

cult to decide what?s safe to give them. An

anti-matter bomb may be clearly too power-

ful, but what about a light-sabre or a jet-

pack? To decide such questions, translate

the items into the nearest AD&D equiva-

lents. A gas mask might be equated to a

necklace of adaptation, a jetpack to wings of

flying, or a robot to an iron golem. Then

decide if the analogous magic item would be

acceptable as treasure ? if a necklace of

adaptation is line, so is the gas mask, but if

a cube of force seems unreasonable, a force-

field device probably will be unreasonable,

too.

Keep in mind charges ? or the lack of

them ? while you?re evaluating the items,

since this can make a big difference. An

anti-gravity belt with unlimited usage is

clearly worth more than wings of flying,

while a force-field projector with only two

or three charges remaining is a long way

from being as valuable as a cube of force (a

closer equivalent might be a scroll with

three wall of force spells on it).

Once you know what is and isn?t accept-

able, it will be relatively simple to set up the

adventure with a suitable selection of trea-

sure. If the PCs do manage to get their

hands on something you don?t want them to

have ? or if you want to let them use an

item in the adventure but not keep it for-

ever (they may actually need a force-field

device at some point, for instance), there

are other steps that can be taken. The sim-

plest is to rule that technological items

above a certain level of complexity simply

don?t work on the PCs? native world (the

laws of nature don?t permit it to operate

there), or that passage through the dimen-

sions has damaged them so that they?re no

longer functioning. The same principle can

be used to keep spell-casters from retaining

any special spells they may have acquired in

other worlds.

If PCs do bring something back in work-

ing condition, they will still have problems.

Knowledge, for instance: can they learn the

secrets of controlling an android or an anti-

gravity platform? If it?s damaged, can they

repair it? How will they recharge charged

items? To keep their treasures working, it

may be necessary to return to the other

world again. . . .

Of course, one can reward player charac-

ters adventuring in parallel worlds with

special treasures to fit the occasion, prizes

that are both unusual and game-balanced.

Any item from a technological world will

appear special in an ordinary AD&D

world,

even if it isn?t devastatingly powerful.

Magic items can be distinctive, too; adven-

turers might return from an Egyptian world

with one of Isis? special charms, or from an

American Indian plane with a sacred medi-

cine bundle. These items that would appear

quite out-of-the-ordinary on worlds without

those mythologies. Carefully chosen, such

items can give the players real satisfaction

without overloading their characters with

power. This is not to say you should never

give a group a spectacular magic treasure

? but think it through carefully first. It?s

far better to give PCs too little and to make

it up later than to give them too much.

The parallel world ideas given here are

not ? I repeat, not ? intended as the basis

for anyone?s primary campaign. It?s one

thing to encounter illusionist kobolds or

DRAGONQUEST air mages as a special

feature of a parallel world and quite another

to establish them as part of your regular,

primary earth; you can?t rationalize a vari-

ant game by saying it?s set on an Alternate

Material Plane: Just passing through an

unorthodox world shouldn?t wreak game

damage if you?re careful, but making some

of these ideas part of your regular game

could lead to major imbalances and distor-

tions. The same applies to starting an ordi-

nary AD&D world and then shifting

permanently to a variant one.

There is also one final warning that

should be added: Always keep the players?

satisfaction in mind. No matter how differ-

ent or original your world is, don?t assume

the sheer novelty of the setting will make up

for any flaws in dungeon design; setting a

dungeon beneath Lankhmar will certainly

enhance the game, but it won?t make your

players overlook any shoddiness in your

work. This is true even if you?re using an

original fantasy world or an established one

they don?t know about ? in those cases,

you can?t count on your world holding their

interest without a good adventure to go with

it. If players dislike a world, don?t use it at

all; the best DM on earth can?t make me

enjoy a trip to a BOOT HILL campaign (I

do not like Westerns). Also, make sure the

game balance doesn?t tilt too far against

your players. New worlds should be exciting

challenges, not killer dungeons on a grand

scale,

Caer Sidi <check to see if demi-plane or full PMP>

The Frozen Lands <check to see if demi-plane or full PMP>

Like any artistic performance, a

dungeon?s success depends on the judgment

of the audience. Don?t be content to have

your players admire your artistry. Reach

but and invite them to become part of the

scene.