-

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most creatures which can fly do so by means

of wings,

either natural or magically augmented

(as in such inherently magical beings

as demons && devils,

dragons,

griffons,

etc.).

Most winged creatures must be constantly

flapping their wings to provide enough thrust to keep their weight in the

air.

Some creatures are light enough and powerful

enough to allow them to actually hover in one place,

but most must be constantly moving forward.

This means that aerial combat is nearly

always going to be a swoop and slash,

hit-and-run affair.

Grappling of opponents in the air will

generally result in both of them plummeting to the ground,

unless they are at a high altitude and

disengage almost immediately.

Even then, it is a risky business.

Only beings with the ability to hover

(gained either through quick and powerful wings or some form of magical

flight)

will be able to engage in combat that

resembles the round-after-round melee system employed in ground battle.

It will therefore be seen that maneuverability

is of prime importance in conducting aerial combat.

Flying combatants -- whether they are

eagles or dragons, men mounted on broomsticks, or hippogriffs --

must make attack passes at their opponents,

wheel about in the air, and attack

again. Those which are more maneuverable

will be able to change

direction and speed in a shorter time

than those which are less maneuverable,

and thus have some advantage in pursuit

and avoidance.

To conduct an aerial battle, a DM must

know the SPEED, maneuverability

and attack modes

of each creature involved.

A ranger and his griffonmount face

off

against wyverns high in the air.

SPEED of flight of each creature is listed

with the other information in the AD&DMM,

and it will be noted again in the list

of aerial creatures at the end of this section.

When conducting aerial combat that takes

place entirely in the air,

it will be convenient to convert inches

per turn to inches (or hexes) per round.

For the sake of standardization,

They will be able to climb one foot

for every three feet they move forward,

but they may dive up to one foot downward

for each foot travelled forward

(i.e., at a 45-degree angle.

None of the above applies to creatures

with class A maneuverability,

which can move in any direction they choose.).

When diving, all creatures' physical attacks

will do double damage to all targets which are not themselves diving.

This includes diving attacks at earthbound

creatures which come from a height of 30 feet or more.

There is no damage penalty for attack

while climbing.

No creature will be able to climb above

5000 feet (due to lack of breathable air) as a general rule,

but you may alter the ceiling if you wish.

Naturally, every type of flying creature

maneuvers differently from every other type,

but in order to make the game playable

and aerial combat

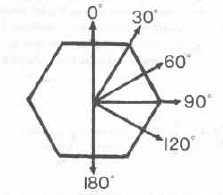

possible, maneuverability has been broken

down into five classes.

These vary from A to E, most maneuverable

to least maneuverable.

Note that the stated amount the creature

can turn per round assumes that the creature is moving at full speed.

Creatures moving at half speed turn as

one class better.

Winged creatures cannot move at less than

one-half speed and remain airborne (except for class B).

Creature can turn 180° per round, and

requires 1 segment to

reach full airspeed. Creature requires

1 segment to come to a full stop in

the air, and can hover in place. Class

A creatures have total and almost

instontoneous control of their movements

in the air. Examples: djinn,

air

elementals,

aerial servants, couatl.

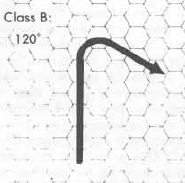

Creature can turn 120° per round, and

requires 6 segments to

reach full airspeed. Creature requires

5 segments to come to a full stop in

the air, and can hover in place. Examples:

fly

spell, sprites, sylphs, giant

wasps, ki-rin.

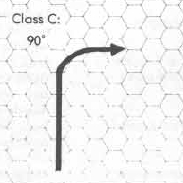

Creature can turn 90° per round, and

requires 1 round to reach

full airspeed. Examples: carpet or wings

of flying, gargoyles, harpies,

pegasi, lammasu, shedu.

Creature can turn 60° per round, and

requires 2 rounds to reach

full airspeed. Examples: pteranodons,

sphinxes,

mounted pegasi.

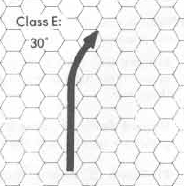

Creature can turn 30° per round, and

requires 4 rounds to reach full airspeed.

Examples: dragons,

rocs, wyverns.

Attack Modes:

As mentioned previously, grappling in

the air is usually out of the question.

This means that many different creatures

will use considerably

different combat tactics in the air, and

their "natural" methods of attack

will often be substantially altered.

The following list should help the DM

determine how certain creatures will fight in the air.

SPEED && maneuverability class

are also listed.

For reasons of space or redundancy,

not all flying creatures have been included.

Once familiar with the system,

the DM should be able to apply it to any

aerial monster.

Conducting aerial combat will be much simplified

if the DM will

remember that most flying monsters simply

cannot execute complicated

maneuvers like barrel rolls or loop-the-loops.

Most can do nothing more

than climb, dive and/or turn, and all

of these actions are easily simulated

and quantified using speed and maneuverability

classes.

There are two methods you can use to conduct

aerial combat. The first

way is simple but less accurate. The second

method is more accurate but

requires the use of hex paper or a hex

map. Though both can be done on

paper, the best way to visualize the relative

positions of the combatants

is to employ miniature figures or paper

counters. A running record of

absolute (or relative) altitude should

be kept, either on a separate sheet

or on a small piece of paper under each

figure or counter.

The simple method

is to move each flyer in the direction they are facing

at the beginning of the move, and execute

the turn at the end by simply

refacing the flyer in its new direction.

Speed would be in actual inches of

movement, or some ratio thereof.

A more accurate method

entails the use of hex paper so that actual arc

turns can be indicated, and so that these

turns may take place at any

time during a move.

Turns will actually take place through

several hexes (the only exceptions

to this are creatures from the elemental

plane of air, which can turn on a

dime in any direction they wish). A turn

need not be executed through

consecutive hexes. To illustrate, here

are possible variant turns for a class B

flyer, which can turn up to 120° in

one round:

The orders for the first example would read: Straight 1, right 60°, straight 3, right 60°, straight 1 .

Each flyer can move 1 hex per 3" of speed;

thus, a gargoyle,

with a speed of 15", could move 5 hexes,

while a griffon, with a speed of 30",

could move 10.

Keep in mind climbing and diving speed

alterations.

In both the

simple and complex methods, movement should be simultaneous.

If there are several players involved,

you may wish to have

them write out their moves ahead of time

(the DM, of course, is not obligated

to do this). If two opponents are clearly

making for each other, and

it is within their ability to intercept

but their written orders would cause

them to miss, some slight adjustment should

be made.

Aerial Missile Fire:

For all missiles fired in the air,

treat short range as medium (-2 to hit)

and medium range as long (-5 to hit) as pertains to chance of hitting.

Fire at objects at long range will always

miss.

The above applies to missile firers on

flying mounts or using a broom or wings of flying only if they have spent

several months in practice.

Otherwise, they will not be able to hit

at all.

The range penalties also apply to missile-firing

creatures such as manticores (treat as composite long bow as pertains to

range).

Note that the above applies only to those

who are moving.

Those hovering with a fly spell or on

a carpet of flying will suffer no penalties.

Those levitating will be penalized as

delineated in earlier subsection Attack Modes, Men: Levitation.

Dragons and similar creatures with breath weapons (such as chimerae) will have a slightly harder time hitting other flying creatures. For this reason, moving aerial targets of flying dragons add +2 to their saving throws.

Any winged creature which sustains damage

greater than 50% of its hit points will be unable to maintain flight and

must land.

Any winged creature which sustains more

than 75% damage will not even be able to control its fall,

and will plummet to the ground.

This simulates damage to the wings,

as in aerial combat,

the wings will be a prime point of vulnerability.

Feathered

wings are not as easy to damage as membranous wings,

and in flight should

be given an extra HP value equal to one-half the normal

HP

of the creature they support,

for the purpose

of figuring how much damage need be taken before the creature can no longer

fly.

Thus, a griffon

with 30 hit points would add an additional illusory 15 points in aerial

combat,

for a flight-damage

total of 45, and thus would be able to take 23 points of damage before

it would be forced to land.

In contrast,

a membrane-winged

creature like a succubus with 30 hit points would only be able to sustain

15 points of damage before it could no longer fly.

Under no conditions are the extra flight-damage

points to be added to the monster's actual hit points for the purpose of

absorbing damage.

A flying monster will only be able to

sustain the normal amount of damage it usually takes in order to incapacitate

or kill it, i.e.,

if the exemplary griffon above takes 31

points of damage from dragon breath, it is dead.

As a final note,

remember that heroic aviators who leap

into the saddle of their hippogriff and rise to battle without taking a

couple of rounds to strap in will tend to fall out in the first round of

melee,

and it is 1-6 hit points of damage for

every ten feet they fall (up to a maximum 20-120 points).