IMPROVING PLAY

-

IMPROVING PLAY

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Both beginning and experienced players

become used to game

habits that can cause problems for the

adventuring party, and

make the game less fun than it could be.

This section contains

playing recommendations that can relieve

these difficulties. It is

intended for players who wish to improve

their level of play.

These tactics are grouped into three categories:

expedition planning,

speeding play of the game, and effective fighting.

Many times the success

or failure of an adventuring expedition

or quest is determined before the party

leaves its base of operations.

More often than not, it is the party’s

failure that is thus

determined, for they have failed to take

some vital feature of the

adventure into account, or have neglected

to bring along some

essential piece of equipment or information.

Scouting and Information Gathering

Before a group of characters leaves on

an expedition, they

should make strong efforts to learn everything

possible about the

adventure’s setting. Interviews with NPCs,

exploring the

approaches and periphery of the goal,

and using magic to gain

insight into the party’s objectives and

potential obstacles can all

save great headaches later on.

When seeking out and talking to NPCs about

the adventure,

the need for secrecy must be balanced

against the likelihood of

gaining useful information. Even rumors

should not be disregarded,

for often such talk has a basis in fact.

If rumors or hearsay

indicate the presence of a certain kind

of monster, then

appropriate measures should be taken if

possible. If someone

reports hearing of basilisks slithering

through an underground

locale the PCs wish to explore, then wise

characters bring along

a few mirrors.

Scouting as much of the area as possible

before entering it is

another sound tactic. A scouting mission

should comprise characters

traveling much more lightly than they

normally would, and

the typical tactic of a scouting party

is to avoid combat at all costs.

One or two thieves, possibly aided by

invisibilityspells, pofions of

gaseous form, or some other magical protection

can discover a

great deal of information for the party.

Don’t forget to scout during the course

of an adventure either!

The commonplace action of listening at

a door before smashing it

open is a scouting function. Whenever

possible, at least one

character should get a look at an area

that the party will be entering

before the whole group gets there. This

not only reduces the

risk of ambush, but also greatly increases

the tactical options

available to the group if they find themselves

engaged in combat.

An underground expedition of any length

should entail considerable

planning and preparation. The objectives

of the mission,

the length of time

it should require, and the areas to be explored

all need to be considered.

The objective of an adventure is often

a result of the story that a

DM has created. Ideally, the objective

is a task that motivates the

PCs toward its accomplishment-if not,

the adventure is off to a

bad start already!

The PCs must be prepared to climb or descend

cliffs, cross

water (by swimming or boat), provide light

sources, feed themselves

for an extended period of time, and still

be able to return to

the surface. Smart adventurers carry more

food than needed.

This way, if opportunities for further

adventuring or exploring

arise in the midst of the expedition,

characters are not restricted

by supply considerations.

The type of transportation that the expedition

employs is worth

serious discussion. Of course, if the

going is extremely rough,

with much climbing down steep surfaces

and squeezing through

narrow passages, the characters must almost

certainly travel on

foot, carrying all of their belongings

in backpacks.

Waterways often provide easy access to

underground regions

far from the surface. Characters traveling

by boat can carry a

great deal more equipment than those walking,

and can travel

faster and easier than their land-bound

counterparts. Water travel

incurs its own set of risks, however,

and underground waterways

in particular are notoriously dangerous

and unpredictable.

A placid stream can suddenly turn into

a churning cascade or disappear

through a small crack, effectively blocking

further exploration.

Where water is unavailable, but the going

is relatively smooth

for long periods, characters might consider

aiding theii expedition

by using beasts of burden. Mules are the

most commonly

employed animals in this capacity, but

dogs can also carry some

weight in saddlebags. Dogs provide the

additional advantage of

guarding the party during periods of rest,

and increase the

group’s attack potential as well.

Using Beasts of Burden

Mules +

Dogs +

As a general rule, characters fight more

effectively if they have

been together for a long time. This is

a natural outgrowth of xperience,

as each character’s strengths and weaknesses

are

revealed, and trust, as companions learn

to rely on each other.

While trust must be developed over time,

a party can practice

cooperative fighting techniques from the

very start.

A well-organized party defines roles for

all characters to fill during

combat. Ideally, these roles are suited

to the characters’

strengths. At the most basic level, this

involves keeping the fighters

with low Armor Class between the monsters

and the rest of

the party.

More sophisticated planning should include

some simple tactical

plans for different situations. If a party

is retreating from a foe

in the middle of a melee combat, which

characters take the rear

guard? What spell might the magic-user

employ to confuse or

discourage pursuit? Who is responsible

for scouting a safe path

of retreat?

Often characters benefit by forming mini-teams

within the

party. A given fighter, for example, might

act as a bodyguard for

the magic-user. The mage can then cast

spells to benefit the

entire group, or use magic that benefits

the bodyguard. Another

fighter might routinely create a diversion

at the start of a combat,

drawing a monster’s attention away from

a thief who is waiting for

a chance to sneak behind the foe.

Probably no single tactic is as important

as surprise. Effective

scouting, of course, is the best way for

a group of characters to

avoid being surprised, while moving silently

without light sources

is the best way for PCs to surprise an

opponent. Ranger characters

are the least susceptible to surprise

and the most likely to

cause surprise, but human rangers underground

suffer grievous

disadvantages because of their lack of

infravision. Half-elven

rangers are very effective in this environment.

While surprise

primarily depends upon keeping a party’s presence

secret from the opponent, it is not always

necessary to conceal

the party. A diversion created by the

party or simply taken

advantage of at an opportune time can

so distract a foe that the

PCs can approach with little regard for

stealth.

Diversions can be accomplished with any

of a wide variety of

magical spells, as well as other character

actions. A single character,

for example, can take upon himself the

task of drawing the

attention of a group of monsters away

from the rest of the party.

Fires are excellent diversions since they

often require the immediate

attention of the monsters in order to

prevent the flames from

spreading. Other acts of sabotage, such

as collapsing a bridge,

tunnel, or dam, can often be devised.

Clever characters might

even work out remote control systems for

diversions: a long

rope, for example, might be tied to a

statue and yanked to topple

it. Alerted by the crash, the monsters’

attention is natur

directed to the statue rather than the

PCs. Of course, if intelligent

monsters notice the rope, the plan does

not work as well.

In fact, monsters-particularly intelligent

ones-do not automatically

fall for diversions. In most cases, monsters

with reasoning

ability but generally low Intelligence,

such as orcs and ogres,

direct their attention toward a diversion

for Id4 rounds unless

something else attracts their attention.

Monsters of medium to

high Intelligence should be allowed a

saving throw vs. spell to see

whether they are fooled by a diversion.

Monsters of genius level

Intelligence can only be fooled by very

clever diversions in which

the PCs’ presence is not easily discerned.

Player characters never get a saving throw

if a monster uses a

diversion against them. Whether the PCs

fall for a diversion or

remain alert to a surprise attack is purely

a matter of role playing.

The pace at which a gaming session proceeds

is in many ways

a matter of group taste. Many players

wish to advance the plot of

the adventure rapidly, with few sidetracks;

others much prefer

savoring each xperience

as a role-playing event, making all or

most of the decisions possible for their

characters, regardless of

how mundane. This diversity is healthy,

and represents one of the

strengths of role-playing gaming.

Wasted time, on the other hand, is a bane

to all campaigns,

regardless of the pace of the adventure.

Squabbling among players,

failure to cooperate, and incessant arguing

with the DM are

common causes of wasted time. So, also,

is failure to decide

upon a course of action.

SOPs (Standard Operating

Procedures): <alt>

The rate of play can also be increased

by parties who have

adventured together a few times, if the

players prepare a series of

standard procedures for common problems.

Open

doors procedures can be adopted and standardized, for example.

Players should prepare a rough sketch

showing the location of each PC

during a door-opening attempt. The role

of each character (such

as guarding the rear, picking the lock,

or ready to shoot an arrow

into the room) should be carefully defined

for the DM. Then, when

a door-opening situation arises, the players

simply declare that

they are using their door-opening drill

(or “door opening drill #2”)

and the DM does not need a statement of

intent from each of

them.

Marching Order:

In addition, standard marching orders for most common types

of environments should be prepared and

sketched. Players

should plan for corridors of various commonly

encountered

widths, as well as large areas where the

walls to either side are

distant. Players may also wish to note

standard weapons carried

while marching. None of these preparations

mean that the PCs

are locked into one procedure all the

time.

Changes in standard

plans simply need to be communicated to

the DM. Remember,

however, that it is much easier to communicate

such changes

than to continually give a description

of what is essentially the

same marching order.

Caller: The

idea of the caller--the character who declares the actions

of the whole group--has been dropped from

many RPGs. Often, when characters are first learning to play, no single

character is quite ready to be an effective

caller. Other beginning

players may feel that the caller prevents

them from getting

the full gaming experience.

If your group does not employ a caller,

and player's {experience}

frustration at the rate of play, perhaps

the idea should be reexamined.

Experienced players have a much easier

time delegating

the tasks of caller to one member of the

party while

maintaining the involvement of all the

characters. The caller can

serve a vital function in keeping the

party moving and avoiding

those lulls where no one wishes to make

a decision. This method

works best when the task of caller rotates

through the group,

changing every game session.

Arguing, whether with the DM or with other

players, is a harder

problem to deal with. If a player attempts

to dominate play, ordering

other characters around or summarily vetoing

courses of

action suggested by other players, peer

pressure is probably the

most effective method of changing this

player’s behavior. If the

other players, including the DM, can point

out the effect of the

bossy player’s pronouncements, he might

well be persuaded to

stop.

CREATIVE UNDERGROUND SPELL USE

Many AD&D@

game spells have obvious applications either

above or below ground. Others are developed

through play or

experimentation.

It is always wise to have all spellcasters

in a party briefly discuss

their spell selections, so that the party

winds up with a

balanced selection of offensive, defensive,

restorative, investigative,

and scouting spells. Be sure to consider

the applications of

reverses of spells that are reversible.

Finding uses for spells that often go

unused can be a lot of fun

for a creative spell-caster. Some tactics

that have worked well in a

variety of campaigns are provided here;

try to invent more of your

own.

Look over the lists for spells that you

might have discarded at

an early level as less useful than others.

Augury,

divination,

and

find the path spells can be very useful

in the underground. Do not

overlook the protective benefits of magic

mouth, glyphs of warding,

fire traps, and rope trickswhen preparing

to go to sleep. In an

underground environment, cloudkill, stinking

cloud, dig, transmute

rock to mud, and disintegrate spells can

all prove deadly to

an enemy. When a party occupies the high

terrain in an underground

setting, a timely raise waferspell can

call down a sizable

flood, while a lower water spell can cause

serious problems for

enemy boaters. Enlarge spells often provide

an effective means

of blocking a passageway, and reduce can

serve as a means for

removing a barrier. Warp wood can have

a similar effect upon

doors.

One technique used

to good effect in several campaigns is the

silence

spell cast upon a coin or small gem. When carried, the

enchantment benefits the party. In an

encounter, the coin can be

thrown among enemy spellcasters to silence

their efforts at spell

use.

Darkness

is an effective spell if a party of humans without a

light source encounters creatures with

infravision. If characters

are proficient in blindfighting, the aid

of the darknessspell (which

of course blinds infravision as well)

can be quite dramatic.

Creative uses for spells such as telekinesis

are not hard to

come by. For example, a character might

seal green slimes and

other deadly creatures into clay or wax

pots. Using telekinesis to

position them over the enemy, the pots

could then be dropped,

with the monster serving as a deadly missile

weapon. Of course,

such pots could be hurled without the

use of a spell. Likewise,

clay pots loaded this way could be left

in the attacker’s path and

then broken with shatter spells.

Most players understand the value of questioning

monsters

and other enemies that are captured. The

use of charm spells

can aid this process immeasurably.

While offensive magic is often quite effective,

it, too, can be

augmented with some creativity. Walls

ofstone, ice, and iron can

be cast in such a way that they immediately

topple and crush

monsters within the area of effect. Ricocheting

a lightning bolt

can cause dramatic, if somewhat unpredictable,

results.

The UA

tome lists the languages of undercommon

and sign language that are commonly known

and employed

by the denizens of the Underdark. In addition,

such subterranean

races have evolved a language based on

patterns of tapping.

This language can be expressed by clicking

stones together,

beating on a drum, or creating any other

pattern of sharp sounds.

Because underground passages create amplified

reverberations,

this language enables communication over

very long distances

when drums are used.

The language is much slower to use than

either sign or spoken

languages, however. Communication takes

approximately 10

times as long as with any spoken language.

Player characters

who are from the underground know this

language.

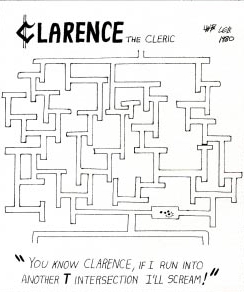

<block>The

most common style of mapping for characters exploring an underground setting

is the detailed graphing of each 10-foot block of corridor explored ||

room entered. <block>

This style, while usu. providing a reasonable

copy of the map the DM is using,

has several weaknesses.

For one thing, this type of map requires

a great deal of time -- both game

and real time -- to make.

<(You can map 4 squares in 1 turn.

Cf. THE FIRST DUNGEON ADVENTURE)>

PCs must carefully pace out dimensions,

and the mapper must take the time

and effort to record them accurately on

the graph paper. A party

otherwise able to travel in complete darkness

must maintain a

light source for their mapper, making

it much easier for the denizens

of the dungeon to spot them.

Another problem with this type of map is

that players tend to

agonize over minor errors. If a room overlaps

into an AREA where

the map shows a corridor runs, the players

worry about teleport

traps and other reality shifts, when the

most likely explanation is

that the map is off by 10 or 20 feet.

Of course, such maps are valuable if careful

attention to detail

and dimensions are necessary for some

reason. In most cases,

however, the main purpose of the map is

to show the characters

the way out of the

dungeon after the adventure, so such an elaborate

illustration is clearly overkill.

If players are not especially concerned

with the exact dimensions

of an area they are exploring, a line-drawing

map can work

very well. In this case, the mapper simply

draws a line to indicate

the path of a corridor or tunnel through

which the party is moving.

Doors are indicated with the standard

symbol, and crossing corridors

or branching tunnels can be displayed

with additional lines.

The exact distance moved becomes a matter

of educated guesswork.

Such a map serves admirably to show the

characters the path

when they wish to retrace their steps

and leave the dungeon. It

also effectively displays the areas that

have been explored, as

opposed to those that have not. Intersections

and doors can be

easily spotted. Best of all, the map can

be drawn without slowing

the party down. Although a

light source is still required, the light

can be shone temporarily while the mapper

quickly sketches in

the last 100 feet of corridor, and then

extinguished while the party

advances.

A line drawing map provides insufficient

info if the party

is traveling through an extremely complicated

or confusing AREA

such as a maze or a convoluted network

of caverns. Other than

these cases, however, players may find

the line-drawing map to

be every bit as effective-and a lot more

convenient-than the

typical graph paper masterpiece that most

exploration missions

generate.