Dragon 77

Dragon 77

| Curses | The Ecology of the Unicorn | Elemental Gods | The Tarot of Many Things | Cursed Magic Items |

| - | - | - | - | Dragon |

He or she?

Dear Editor:

I enjoyed Mr. Greenwood?s article concern-

ing the Nine Hells [issue #75]. However, I

found one apparent mistake. In the article,

Sekolah is described as a female.

The Deities &

Demigods Cyclopedia states that the deity is a

male. Can you explain?

Greg Lewis

North Augusta, S.C.

Yep, the article was ? technically ? in

error. But I think we can figure out where Ed

Greenwood was coming from when he referred

to Sekolah as a female shark (see

page

31 of

issue #75). In the entry for sahuagin

in the

Monster Manual, it is noted that ?the religious

life of these creatures is dominated by the

females.? The reference to ?females? in that

passage specifically concerns female sahuagin,

who are the clerics of the race.

But, carrying the interpretation of that

statement a little further, it makes sense for a

religion ?dominated? by females to have a

female deity at the top of their hierarchy, and

it seems safe to assume that this was how Ed?s

reasoning worked when he called Sekolah a

?she.? In light of the fact that the Monster

Manual is part of the official

AD&D?

rules and

the DEITIES & DEMIGODS?

Cyclopedia is

not a rule book in the same sense, it might be

argued that the MM takes precedence over the

DDG book on this point. Fortunately, for the

purposes of playability, it makes no difference

(that we can see) whether Sekolah is male or

female. We won?t disagree with anyone who

thinks the article was in error, and you can cer-

tainly change ?she? to ?he? anywhere the arti-

cle talks about Sekolah if you?re more comfort-

able with that. ? KM

Elemental gods

A four-part approach to campaign deities

by Nonie Quinlan

Most role-playing game referees, in laying out their cam-

paigns, have no trouble finding suitable gods. For “good-bloody-

fun” campaigns, which include most FRP worlds, the general

rule is: The more gods the merrier, and the more wars between

the gods the better. In these warlike universes, gods should be

killable by high-level characters and they should be clearly rec-

ognizable as belonging to one race and one alignment, On the

other hand, campaigns designed for medieval authenticity will

tend to reproduce the medieval church: a highly organized

clergy, with a single abstract deity who never takes a direct part

inthe action.

But there is a third, rarer type of campaign that could be called

the “high fantasy” style. It tends to involve consistent, non-

anachronistic worlds; you will never hear “Frodo’s Pizza Parlor,

may I help you?” or “You . . . you mean this whole dungeon is

one big pool hall?” The characters have real motivations, and

will not jump into an abyss just to see how deep it is. They are

part of an ongoing history which they respect; upon discovering

a great hero’s tomb, they will pour libations and pray for him,

not try to figure out how to loot the tomb. The role-playing is

well thought out, consistent and realistic, and the highest part of

the game is not the loot and experience, but the sense of wonder.

Gods for such a campaign are hard to find. It is necessary that

they be of a kind that a real person could take seriously, because

the characters are going to be serious about their religious

beliefs. The gods must be more than super-powered beings,

because a strong and independent adventurer is not likely to

worship a god just because the deity has more hit points than

any others and better powers. On the other hand, it must be

remembered that in the campaign world the gods are real, not

simply manifestations of cultural religious beliefs; why would

there be one god for gnomes and another

for orcs? Fire is fire.

For the gods to be taken seriously by both the players and their

characters, it is necessary that they be all-powerful, all-knowing,

and truly immortal. For this reason they should not be assigned

formal attributes; they need no armor class or hit points, because

no creature of this world could harm them. They have infinite

strength and unlimited power, and only the nature of what they

rule constrains them; a god of fire will rarely control water.

Because they are so powerful, it is clear that they must not be

hostile toward each other, or the world would have been de-

stroyed in their first conflict. Their powers must be balanced,

equal, and approximately at peace. For this reason, the four ele-

ments seem a good model for the nature of the gods, because the

elements have always existed together without serious conflict.

(Certainly water and fire, for example, may be mutually destruc-

tive on contact, but neither seems dedicated to locating and de-

stroying the other, and both still exist as they always have.)

The requirement that the gods be at peace with one another

also calls into question the assumption that a god has an abso-

lute alignment. If there are truly good gods and truly evil gods,

they will not endure each other’s existence. But the elements, like

any force of nature, unite both positive and negative aspects in

themselves; without fire, civilization would barely exist, and yet

fire is the great destroyer. And what could be more ambivalent

than the life-giving, life-taking sea?

It is for these reasons that our local D&D® gaming group has

developed a pantheon based loosely on the four elements and

given them the characteristics described below.

The nature of the gods

There are four gods: those of Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. They

are not hostile to each other, or to each other’s followers. Each

may be worshipped by someone of any race or alignment; they

have many natures, and every worshiper may see them differ-

ently. They encompass opposites; good characters and evil ones

may worship the same god, even if they pray at different fanes.

The gods are not limited in gender any more than in align-

ment; they may tend to be associated with one sex, but certain

aspects will be of the opposite gender, or both, or none.

They rarely take an active hand in matters; they give power to

their clerics and may answer prayers, but they do not wake up in

the morning and decide to start a war. They are all-powerful,

non-corporeal beings, but once in a while one aspect of a god

may take apparently physical form and walk on the earth; even

in that form they cannot be injured or constrained. The average

character stands a good chance of seeing a god at least once in

his life, which may seriously affect his religious beliefs.

The nature of religion

In developing religion within a culture in a campaign using

elemental gods, it must be remembered at all times that the gods

are real and the people know it. Oaths sworn to the gods must be

honored, or retribution will fall on the oathbreaker; this is an

absolute law, as certain as a law of nature.

The gods do not demand worship. It is the nature of men to

worship the divine, and so most men will perform religious ritu-

als, offer prayer, and otherwise deliberately affirm their relation-

ship to the gods. Other men may never perform an act of wor-

ship in their lives, but they too are aware that the gods exist.

When the gods are clearly real, there can be no atheists.

In my campaign, I assume that each character has a closer tie

to one of the gods than to the rest. It is to this god that the char-

acter prays most often, and this god is most likely to help the

character in times of need. However, characters are not therefore

hostile to the gods they don’t worship, or even to other aspects of

their own gods. They know the gods exist and they honor them,

but each character’s greatest devotion is given to his own deity.

An analogy to this in our own world might be the tradition of

patron saints.

Members of the priesthood, both spell-casting clerics and the

little village priests who perform marriages and bless the crops,

must be sincere in their beliefs, not hypocritical and avaricious,

because the gods know the truth of their oaths of service. This is

also true of such people as knights, kings, and judges; they may

be mistaken or misled, but they must be true to their vows.

Details of religions vary from culture to culture, but the aver-

age man’s life is much like what we would expect. He asks the

priest’s help with the rituals of birth, marriage, and death, and

the priest’s blessing on the spring planting or the launching of

the fishing fleet, and he will later offer thanks for the harvest or

the catch. With his family, he shares the lesser rituals of the table

and the day’s task, and alone in the night, or when he is greatly

moved, he will speak to his god in spontaneous prayer. Belief

will not dominate his life and his actions, but it will always be

present, because he knows the gods are real.

The Elements

A system of gods based precisely and exactly on the four ele-

ments is actually likely to be both dull and confusing. How

worked up can someone get about the divinity of granite? And

on the other hand, what element is a thunderstorm? The rain is

Water, the wind Air, the lightning Fire. Is a volcano Earth or

Fire? And what possible element is a human?

In our local gaming community, we have three established

Dungeon Masters using a system of elemental gods, and several

others just beginning. In no two campaigns are the gods entirely

alike, because no DM uses a technically pure elemental system; if

it were not colored by the personality of the gods and of their

worshipers, it would be not a religion but a science. In the de-

scriptons of the mythologies below, two campaigns’ versions of

each god are given to show how they can be varied according to

each referee’s desires.

A word of caution, from experience: Be careful about the ten-

dency to use standard god-figures. It is almost automatic to

assume that the Earth is a fertility god, the Fire a sun god, and so

on. But these set-ups will degenerate quickly into monotony for

players and DM unless the DM has a complete understanding of

how they work, what opposed natures they represent, and how to

make these “facts” real to the players. While I have had success

with an Earth fertility goddess myself, it is an uphill struggle,

and I have never seen a sun god well and interestingly handled

in a fantasy campaign. A certain amount of originality, if

handled consistently, will yield a much richer and more fascinat-

ing system.

The aspects of the gods

The Earth: In my campaign, the Earth is the goddess of birth

and growth. She is primarily a deity of live soil rather than

stone, and is responsible for farming and fertility. Called the

Mare, she rules most animals except the wildest beasts that

belong to the Air, and the animals of highest intelligence that

share man’s ability to choose their own gods. She is most wor-

shipped by humans and halflings, but the elves know that she

gives them their beloved forests, and the dwarves know that it is

her strong hand that holds the stone roof over their heads and

shelters them.

In her evil aspect, she rules the darker side of fertility; plague,

poison and decay, and on the other hand sterility and famine.

Animals particuarly associated with her are the mare, the bull,

and the serpent, and her tree is the apple. Religious symbols and

other objects made in her honor will often be made of copper or

bronze, set with jade, carnelian, or amber. Her colors are green,

brown, blood red, and harvest gold. In prayer, she might be

addressed as Allmother, Giver of Gifts, Earthshaker, Bearer of

Burdens, Mother of Horses, Shepherd of the Trees; in her darker

aspects, Pourer of Poison, Barren Field, Mother of Vipers.

Another campaign in our group has a very different Earth

goddess called the Bear, who is primarily a protector and

defender; she is the goddess of good warriors (who in this world

are gentle rather than fanatical), and she is the youngest and

most personal and friendly of all the gods; not a mother goddess,

but a beloved sister.

The Air: The Air god of my campaign is called the Raven, and

he has two natures; even in his good aspects, he is the god of

both the still air and the storm. In the first, he is the god of

thought and speech, and thus of learning and music. Clerics who

worship this aspect of the Air god tend to live contemplative

lives of meditation.

In his second aspect, he is the god of storms and of wild

things; stags and hawks, werewolves, berserkers, and the Wild

Hunt. It is not far from this to his evil aspect, which rules insan-

ity and the love of destruction. (It may seem difficult to unite

poetic wisdom and cruel violence in one god, but a close look at

Odin’s character in Norse mythology will show a similar

contradiction.)

The Raven’s animals are primarily the wolf, the stag, and the

hawk, and his tree is the pine. His metal is iron, his tones grey

quartz and obsidian. His colors are grey and black; midnight

blue in his sky aspects, pine-green and red as the Hunter. Some

of his titles are: Shapeshifter, Teacher, Father of Wolves, Mask,

Masterbard, Hunter, the Dark-Winged One.

In contrast to the wolf-like, masculine aspect of the Raven,

another campaign sess the Air god more as a cat-figure, more

Dionysus than Odin. This Air god is androgynous, playful, often

malicious, and treacherous when angered.

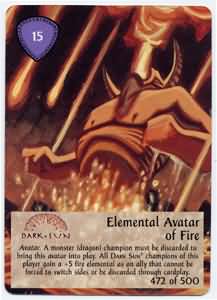

The Fire: The Fire god in my campaign is worshipped as the

Dragon, god of the forge. He is the patron of craftsmen, and

especially of smiths. Dwarves have a particular love for the

Dragon, but he is also responsible for the human’s plowshare

and the elf’s harp. The Fire god is in many ways the god of civil-

ization, because he is the god of tools; not just the hammer but

also tools such as the loom, the saw, the net, and the cookfire.

The Earth may be the goddess of creation, but the Fire rules

creativity.

In his evil aspect he is the volcano and the forest fire; blind,

uncaring destruction that can overwhelm a man or a city with-

out noticing.

The animals of the Fire god are the dragon, the griffon, and

the nightmare; his tree is the oak. Gold is his metal, and his

stones are ruby, topaz, and all clear fire-colored gems. His colors

are red, gold, and white. The Fire god is sometimes called Master

Craftsman, Forgefather, Goldenhand, the Maker, and also Fire-

fang, Flaming Horse, Eater of Cities.

Another campaign has a very similar god, but he also rules

magic and all the ways of the wizard, because magic is seen as a

human act of creation and an act involving the use of skill, and

the essence of magic in this campaign is fire.

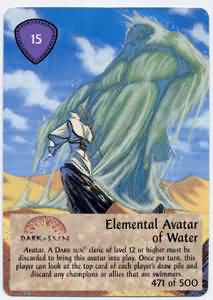

The Water: Because of the connection of the moon and the

tides, the Water goddess of my campaign is the ruler of light, and

therefore of darkness. Called the Moon, she is the most revered of

all the gods. She is the goddess of magic, worshipped most of all

by elves and unicorns. Of all the gods, she is the most purely

good and the most purely evil; both the holiest and unholiest of

characters are her followers. She is the goddess of healing, the

protector of the innocent, the goddess of justice and thus of war,

when it is undertaken for noble reasons.

As the Dragon is the god of the hands of civilization, so she is

the goddess of its heart and mind, and of the things that make

humans more than mere beasts with tools. Thus, her evil aspect

is the destroyer of civilization – not blind destruction, but care-

ful, reasoned, and deliberate evil. One of the two greatest cities

in

my campaign world was brought to ruin by the deliberate

designs of the Moon's evil worshippers, and a conflict fostered

between two innocent races still smoulders centuries later.

The Moon’s animals are the unicorn, the dolphin, and the

gull; her tree is the birch. She is often represented as a horned

hippocampus. Her metal is silver (mithral is said to be made

from her tears), and her stones are pearl, sapphire and onyx. Her

colors are black, white, blue, and green; as the goddess of magic,

grey and purple are also her colors. Her titles include: Shepherd

of Unicorns, White Lady, Silvershield, Protector, Lady of the

Waters, Wavemantle, Shipbearer, and Fairest. In her evil aspect

she is Deathgiver, Shipbreaker, Mother of Demons, Night’s

Queen, Drinker of Blood, and Mistress of the Abyss.

Another campaign has a different Water goddess. Called the

Old One, she is the goddess-of the ocean, in a world where the

only land is a scattered group of islands. It is she, not the Earth,

who gives men food and life, and she who withholds it. She is

the creator and destroyer, the most terrible of elemental forces;

oldest and strongest of the gods, she is the least human of them

all, and to anger her is fatal. Even her clerics fear as well as

honor her.

Conclusion

In the examples above the world has clearly shaped the gods,

as the gods should shape the world. The details of these mytho-

logical systems are given only as an example of two such pan-

theons, not as a rule for all to follow. The great advantage of the

elemental pantheon is flexibility in a framework of consistency.

If adapting such a system to your own campaign, consider

seriously the geography and cultures involved. It can become an

exercise in anthropology: If these people worshipped a fire god,

how would they picture him? How are their beliefs like the

beliefs of other cultures and races?

Above all, remember that in the campaign world the gods are

real. Their worshipers are real. If the players are to maintain

consistent characters within the world, then the gods must also

be consistent, believable, and interesting, not just names and

attributes to which a character pays lip service when necessary.

They must be a living part of a living world.

Each campaign has its own style, and everyone thinks their

own the best, but it seems safe to say that few players whose 50th-

level characters manage to find and kill the evil god of gnomes

have ever felt anything like the awe and the chill felt, not only by

the characters but by the players, when, in troubled times in my

campaign, the city of Arna looked out across its great bay and

saw on a cold early morning, a long-forgotten masculine aspect

of the Moon rise up from the waters to tower high above the

world – his pearl-skinned body still waist-deep in the ocean

while his streaming hair was crowned with clouds.