by Karl Horak

by Karl Horak

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon | - | - | - | Dragon 47 |

The Assassin had no choice but to

allow Balthrad to leave through the Gate

of Rith; he had sworn an oath upon his

alignment to not SLAY Balthrad.

Surely

Eroi the Kind-hearted, demigod of Elysium,

was watching them,

ready to destroy them should one raise his hand

against the other. Armando the <Priest>

then suggested, ďIs death for Balthrad

revenge enough? Let us find him and

sell him into slavery in the North. Assassin, with the power of your

<psychic ability> you

can place him in a trance, NOT to awaken

until you command.Ē So they agreed

that this they would do and the Assassin

told Armando to meditate and use his

powers to find the fugitive Balthrad.

<change Assassin to Bounty Hunter>

Within 30 minutes Armando was projected

astrally and seeking out

his quarry.

In the past I would have simply set an

arbitrary probability and rolled d%. But

the serious consequences of Balthrad

failing to hide from Armandoís astral

search deemed that I should be more

objective. How long would an astral

SEARCH of an AREA require and what

would be the chances of success?

The result of a few hours of geometry and

calculations provided some simple formulas

that can be applied to other cases,

revealed that Balthrad could evade an

"exhaustive" SEARCH easily, and pointed

out the limitations of large-AREA searches,

even when carried out astrally or [ethereally].

Armando enlisted the aid of Rith in

cordoning off the island that was the

lower terminus of the gate. Next he

quickly surveyed the surface of the island,

looking for places of concealment. Failing

that, he would conduct a SEARCH of

the various subterranean lairs, caves,

shafts, and tunnels.

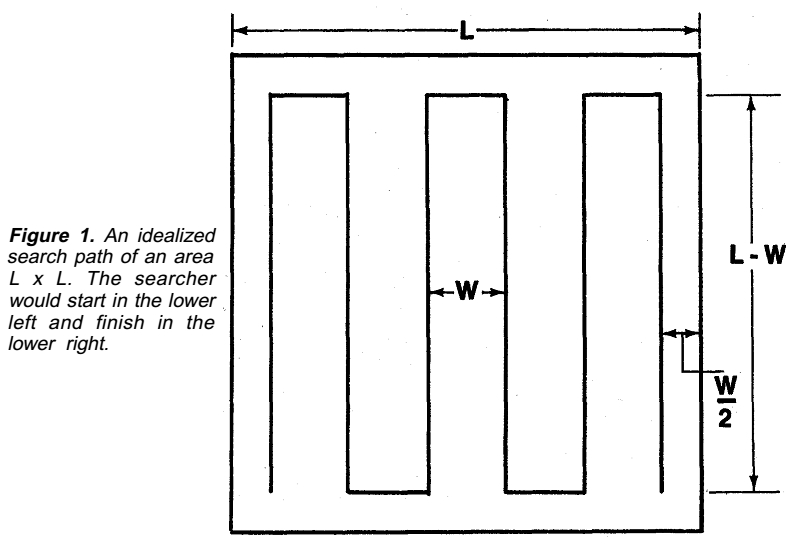

One can derive a formula for the surface

SEARCH by idealizing the AREA to be

searched and the path to be covered as

in figure 1. If L is the length of the side of

the AREA to be searched (the square root

of the AREA) and W is the width of the

SEARCH path (W must be in the same units

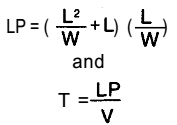

as L, usually miles), then LP is the total

length of the SEARCH path. The formula is

the number of sweeps times the length

of each leg plus the sum of all the short

(connecting) legs:

![]()

Since L is many times greater than W

in most cases, one can substitute L for

(L-W), yielding:

![]()

Dividing LP by the speed of the searcher,

V, gives the Time, T, required for the

total SEARCH. Dividing by the number of

searchers yields the time per character.

DMís using the formula must remember

that values for L and W are to be set

by the player as he or she feels fit in

order to attempt the SEARCH. V and its

associated probability of success fall

into the domain of the DM. The simplified formula

should only be used in the

event that L is about 1,000 to 10,000

times larger than W, in order to keep

errors under a few percent. Depending

on the size of the SEARCH object (whether

single man or long ship), W will affect

the chances of success, as will V. For the

DM to get an idea about the interrelationships of the variables, let

us follow

through with the example from the first

paragraph.

In the case of Balthrad versus Armando, the surface AREA of the island

is 75

hexes, each 5 mi. across, for a total AREA

of 1624 sq. mi., so that L =40.3. The value

for W was set at 50 ft. A certain amount of

subjective judgement is unavoidable in

determining V. Astral travel is at the

speed of thought, yet the senses would

get only a confused muddle at such vast

speeds. Even when SPEED is reduced,

how much can a person sense when

moving rapidly? Let us assume that at 50

mph a person can detect the SEARCH object with a probability of 25%;

at 100

mph this probability drops to 10%; and at

over 200 mph the probability of recognizing a man-sized TARGET is only

1%

These probabilities can be changed to

suit the needs of any particular case.

Adjust them upwards for large or poorly

concealed targets and downward for

small or well hidden ones. Balthrad had

taken shelter in an abandoned dwarven

silver [mine], which I consider about

average for a place of hiding.

Plugging these values into the equations and waving my hands to explain

all

the assumptions produces a SEARCH path

171,000 mi. long. At 200 mph this would

take almost 36 days to cover and only

have a 1% chance of success. Slowing to

100 mph would increase the probability

to 10% at a cost of an additional 36 days.

Itís no wonder that Armando failed to

locate Balthrad in the few days he had

available for the SEARCH.

In the event that Armando was intent

on pursuing the SEARCH underground, I

was prepared with the following simplified formulas for a volume search:

Since a traveller passing through solid

rock and earth has a much more limited

range of senses, the probability of success is reduced to 1% or even

0.1%. This

reflects the fact that the searcher would

miss the target entirely if he was off by

only a few inches. Again, this value is

arbitrary and should be modified to suit

individual needs.

The results of this type of search are

staggering. Assuming Armando tightened the pattern (W = 10 ft.) and

went

500 ft. deep, LP = 6,900,000 mi. and T

becomes almost 4 years. Armandoís

search appears to be fruitless.

Of course, intelligent searches can

eliminate much of the drudgery and

increase the chances of success by limiting the search area and seeking

specific

clues. Armando merely specified that he

would search the surface of the island

and then the labyrinths beneath it. If he

had checked only the nearby mountains,

the most likely hiding place, the area to

be searched falls off to 13.3% of the original, which would take about

5 days. By

frequenting water holes in arid regions,

looking for fires or magical light at night,

and similar maneuvers, the chances of

success will be higher.

The lesson to be learned is that characters attempting to search an

area

of

any great size by flying, astral projection,

or Oil of etherealness will have poor luck

unless they specify the details of their

search behavior. For the luckless searcher on foot or horseback, the

chances of

successfully sighting the target are very

high, but V is so low (compared to 50 or

more mph) that T is prohibitively high.

No attempt has been made here to account for moving targets. A quarry

could

easily precipitate an encounter or completely avoid it with timely

movement.

Another assumption of this model is perfect navigation so that no area

is searched

twice or overlooked. These inefficiencies could add 10-30% extra effort

or reduce the probability of success.

Dungeon Masters should realize that

the chances of finding a creature other

than the target are very high, considering the numerous sweeps and

the need

for the searcher to be seen in order to

see. Even astral and ethereal searchers

will be subject to this hazard, since 6

basilisks are far easier to encounter than

a well-hidden fugitive.

There is one type of search that appears feasible. That is the large-area

search for a target that is easily visible,

such as a boat at sea. In these instances

W can be very large, weather permitting,

and the probability of success can be

very high, even approaching 100%. But

for most attempts at finding a fleeing

character after evasion, there is little

hope for rapid success.