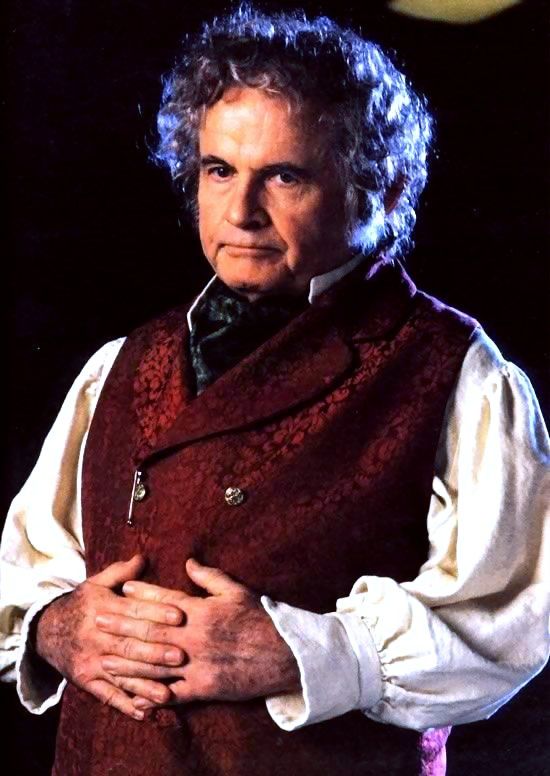

Mention thieves to a band of adventurers,

and every eye will suddenly turn to

stare at the halfling in the next-to-last rank

who has been trying very hard to look inconspicuous.

Mention thieves to a group of players

rolling up a new party of characters, and

someone is bound to ask, ?Do we really

need one of those? The last thief we had

stabbed Roger Ramjet in the back and got

away with his + 4 sword.? Shortly afterward,

somebody manages to come up with

statistics good enough to start a monk.

Mention thieves to a DM, and his or her

eyes will roll while a resigned sigh blows

over the referee?s screen. ?Thieves are a

pain in the neck,? you?ll be told. ?In order

to be sneaky and devious, they have to pass

me notes ? which lets everybody else know

they?re trying to be sneaky and devious.

And then I have to cope with dozens of little

scraps of paper I can only decipher half the

time anyway!?

All those reactions are based on the same

kind of thief ? the nasty little halfling who

filches gems at every opportunity and disappears

at the slightest drop of a twenty-sided

die. Unfortunately, that?s the sort of thief

with which most gamers are best acquainted.

Even the occasional human or elfborn

thief is usually of the same

unpredictable stock, and remains difficult

for fellow adventurers to tolerate on a longterm

basis.

That's a bit surprising, considering the

fact that the thief is the only character class

in the AD&D® game open to

members of

any demi-human race, and that almost no

restrictions exist on the number of experience

levels thieves may attain. Still, thieving

behavior patterns remain stubbornly

entrenched; even in Roger Moore?s excellent

series of articles on the races in

DRAGON® issues #58 to #62 (reprinted in

The Best of DRAGON anthology, Vol. 3),

descriptions of demi-human thieves suggest

that they follow their professional instincts

first and their racial instincts second.

Such a characterization not only doesn?t

make psychological sense, it unnecessarily

limits the potential diversity and range

available to aspiring players of thieves. In

fact, there?s no particular reason that all

thieves have to be marginally trustworthy at

best, or perpetually greedy and selfish at

worst. A thief?s race will almost always have

a profound effect on the way he or she

functions in a game setting, and that effect

won?t necessarily make the character a

liability to an adventuring party. A look at

each race illustrates the differences in outlook

that demi-human thieves possess.

Elven eavesdroppers

As Roger Moore observed in DRAGON

issue #60, elves place a lower value

than

most other races do on personal property,

largely because of their exceptionally long

lifespans. As a result, elven thieves are

likely to use their special skills to acquire

another commodity of more importance:

knowledge. Elves, with their inherent knack

for ferreting out secret doors and their

generally superior senses, are already keen

observers. Add to this a thief?s ability to

hide and move silently, and the result is a

character uniquely suited to gathering all

kinds of information and discovering all but

the most carefully guarded secrets. (An

elven thief residing in a populated area is at

least 75% likely to be aware of any political

or adventuring activity ? including military

movements ? before the normal inhabitants

find out what is going on. This

statistic, of course, applies exclusively to

NPCs and would vary with individual

circumstances.)

That?s not to suggest, however, that elven

thieves are exclusively devoted to uncovering

other kinds of knowledge, notably concerning

the whereabouts of long-lost magics

and mysterious civilizations. These thieves

do spend part of their time researching

likely prospects, either in musty old libraries

or in and around the homes and guildhalls

of various wizards and sages. They are also

adventurers, though, following up the clues

and persistently journeying into remote

areas in quest of abandoned towers and

cities.

On such expeditions, these elves often

employ magic items and carry away plunder

that would ordinarily be neglected by

members of other races. In particular, they

are fond of the various informationdetecting

wands (some have been known to

wear similar devices in the form of rings),

and they are far more likely to collect old

books, scrolls, and tapestries ? magical or

otherwise ? from their dungeon visits than

they are to come home with bags of gold

and silver. Though such treasure may seem

bulky and of relatively low value, elven

thieves can sell any book or artwork of

historical interest for 10% to 20% more

than can their colleagues of other races.

Although elf-born thieves value knowledge

highly ? and are not above making

that fact abundantly clear to characters

seeking it ? they are not as a rule especially

secretive. They will always share information

about their goals and intentions with

adventuring colleagues (though they may

not reveal the full value or power of a

sought-after magical item if they fear a

party member might try to seize or misuse

it), and they are less reticent than most

other thieves about tales of their past exploits

and adventures. Further, while elves

are only rarely members of a thieves? guild,

they will generally display the same high

degree of professional reliability that marks

a guild-affiliated thief on an assignment.

Q. Can elven thieves

use bows?

A. No. Despite

the fact elves are

traditionally master

bowmen, an

elven thief is limited

by the restrictions

of class, in addition

to those of

race.

<Update, UA: Thieves

can use short bows>

(Imagine #9)

The wandering half-elf

The Half-Elf Point

of View +

The number of half-elves who adopt the

profession of thief is relatively small. While

such characters share the enhanced senses

and interest in information of their demihuman

ancestors, they are unmistakably

human in their taste for intrigue and deception.

As a result, half-elven thieves tend to

avoid elvish communities and kingdoms,

instead traveling extensively and mixing

with human society as much as possible.

The half-elf?s abilities set the tone for the

brand of thievery he practices. Half-elven

thieves are masters of the confidence game

and the elaborate swindle, preferring to

make a profit from showmanship and misdirection

rather than by brute force or armed

confrontation. For instance, a half-elf arriving

in a middle-sized town might eavesdrop

on a wealthy magician, then turn up on his

doorstep the next day with a map leading to

the hiding place of a valuable item the mage

just happens to be hunting for. Would the

wizard be interested in buying the information?

What about financing an expedition to

search for the item? Of course, by the time

the spot has been reached, the item is no

longer there ? but the thief has long since

collected his fee and vanished.

While their tendency to shade the truth

makes them potentially awkward traveling

companions, half-elves are generally cautious

enough to make the problem a minor

one, at least in fairly large parties where the

thief is clearly in the minority. (After all,

half-elven thieves do spend a lot of time on

the road, and it doesn?t pay to bite the hand

that?s protecting you.) A half-elf's first

priority in such circumstances is his own

personal safety; in a conflict between potential

profit and potential injury, discretion

will almost always prevail. In fact, a halfelven

thief may go to some length to make

himself useful to a group of adventurers if

he expects to need their protection in the

immediate future ? though his loyalty will

rarely extend to sharing the profits of a

private project. The thief usually won?t stay

with the same adventuring party for longer

than it takes to safely reach the third or

fourth town along the road, where he can

begin a new swindle with little fear that his

reputation has preceded him. (He might,

however, rejoin the party the next time it

passes through if escape is necessary by

then.)

Dwarven locksmiths

The Dwarven Point

of View +

The majority of dwarves belonging to the

?thief? character class are not thieves at all,

in the criminal sense of the word. Rather,

they are experts at designing and crafting

the very locks, traps, chests, and vaults that

other thieves are so eager to bypass or rob.

Just as many dwarves are superb and wellregarded

armorers and weapons makers,

the bulk of dwarven ?thieves? are really

locksmiths, cabinetmakers, or architects

who specialize in keeping things safe from

robbery.

Although many of the dwarves who possess

thieving skills don?t use them to steal

(and frequently don?t even adventure,

instead residing in towns or dwarven communities

where their skills are eagerly

sought by merchants and nobles), they often

practice their crafts for other related purposes.

The 2 most frequently encountered

examples of this are the troubleshooter and

the liberator.

A troubleshooter is a special breed of

locksmith/designer who specializes in testing

elaborate locks and traps for clients worried

abou the safety of their valuables or the

impregnability of their dungeons. Such a

character may be assigned to steal a

piece of jewelry from a locked VAULT or to

break out of a supposedly escape-proof

prison. If he fails, the troubleshooter has

proven the worth of the protective device; if

he succeeds, he offers advice to his clients

on how to prevent future thieves from repeating

the feat. Such service is always

costly, but is utterly reliable and generally

worth the investment if a client wants to feel

truly secure.

Liberators are rarer, but more closely

allied to the usual concept of the thieving

class. These are thieves especially trained

and outfitted to recover valuables that have

already been stolen ? usually from other

dwarves, but sometimes from clients who

pay for the service just as they would for a

troubleshooter. These dwarves (who are

sometimes trained as fighters as well) pick

locks and disarm traps ? frequently remarking

on their inferior construction as

they do so ? in single-minded pursuit of

whatever they have been assigned to bring

back. They are fiercely proud of their abilities

and their dwarvish heritage, and woe

betide anyone who suggests that a liberator

is less than honorable!

Not many dwarven thieves adopt the

adventuring lifestyle, but those who do are

more often liberators than trouble-

shooters, and most of these have been cast

out of dwarven society for some act of theft

against another dwarf or a client or ally. It

is not entirely safe to generalize about these

outcasts; although most continue to be

staunch upholders of dwarven superiority

and of the fierce professional honor that is a

dwarfs trademark, they can also be unpredictable

and occasionally dangerous. Some

outcasts ? perhaps the majority ? have

learned from the mistakes for which they

were banished, and have adapted fairly well

to the benign questing of the adventurer. A

few, however, feel so deeply wronged by

their fellow dwarves that they turn to the

darkest side of the thieving profession.

These unstable characters pillage and destroy

wherever they go, taking special

vengeance on any other dwarves who may

cross their paths and treading periously

close to the ways of the assassin. But these

?dark dwarves? are quite rare, and dwarven

thieves generally make solid, reliable

adventuring partners who are especially

handy in underground settings.

The FUN-loving gnome

The Gnomish Point of View

+

Gnomes, more than any other racial

type, take pure pleasure from the act of

stealing. This outlook, however, stems not

from a tendency toward evil but from sheer

gnomish delight in slipping through intricately

crafted defenses and collecting a

valuable prize. While other races consider

thievery a profession, gnomes practice it as

a recreational pursuit ? with much the

same devotion that DRAGON Magazine's

readers are likely to pursue role-playing

games.

As a result, gnomes are much more deserving

of the title ?burglar? than the halflings

to whom the description is more often

applied. If a wealthy merchant reports that

a valuable jewelry collection has vanished

from the double-locked false bottom of a

chest hidden in his most secret closet, the

odds are good that the thief responsible was

a gnome. If an adventuring party hasn?t

been able to collect a particular treasure

from a nearby dungeon because it?s too well

defended by an intricate series of traps,

their surest solution is to take the problem

to the nearest gnome settlement ? though

it may cost them a fair percentage of the

hoard, any thieves there will be likely to

jump at the opportunity.

Yet while gnomes have developed an

almost legendary reputation for succeeding

at ?impossible? burglaries, they are by no

means infallible. Indeed, their failures are

often as spectacular as their achievements

?and the gnomes do not always mind, so

long as they can get a good story out of the

episode. The reason for this is that gnomes

carry out their thieving activities less by

careful planning and organization than by

instinct and impulse. In this way, a gnome?s

thieving habits are not unlike those of a

pack rat: if he sees something that looks like

an interesting trinket, he is liable to drop

whatever he?s doing at the time to make a

stab at collecting it.

This ?pack rat? mentality also influences

the kinds of objects a gnome will steal and

what he does with them afterward. Gnomes

are, of course, especially attracted to gems

and jewelry (the more valuable, the better);

they are also easily seduced by the lure of

magic items, especially those with some

form of illusion-producing power. They are

not, by contrast, especially interested in

hoards of mere coin or other bulky goods,

since a gnome does not usually sell the

items he steals. Rather, he keeps them to

admire their beauty (in the case of gems

and such) or their magical powers. But as

time passes, gnomes often lose interest in

their less valuable prizes, and have been

known to leave them behind in place of

newly stolen items of greater value ? hence

the comparison to the pack rat. This is

especially true of adventuring gnomes, who

are frequently traveling and cannot easily

amass more loot than they can carry.

Characters whose parties include thieves

of gnomish extraction are usually in little

danger of being betrayed or backstabbed. In

fact, while gnomes are normally reluctant to

start a fight, they are quick to leap to a

friend?s defense. But adventurers who travel

with gnome thieves should be prepared to

make allowances for the gnomes? unique

personalities, particularly in two respects.

First, they should not be surprised to occasionally

find themselves the butt of the

gnome?s practical jokes, which are always

intended purely to amuse (and perhaps to

embarrass) but not to injure. Secondly,

fellow adventurers should be most careful to

avoid short-changing gnome thieves when

the time comes to divide treasure. A gnome

who feels his contributions have been undervalued

or who especially craved a particular

bracelet will not be above collecting

?his rightful due? from a fellow party member,

though the gnome is likely to leave

sufficient gold in his victim?s purse to more

or less balance the shares.

The half-orc's priority

The Half-Orc Point of

View +

Half-orcs of any class don?t seem to be

found in great numbers in the average

gaming campaign; half-orc thieves, if anything,

are found even less frequently. It may

be just as well, for half-orcs make perhaps

the single deadliest sort of thieves a party is

likely to encounter.

Meetings with half-orc thieves, as a rule,

will not occur in dungeons or other remote

settings where an adventuring group is

hunting for hidden treasure. Instead, they

are likely to take place in the dark alleys of

large cities and towns, or on fairly welltraveled

but under-patrolled roads between

such communities. This is because half-orcs

are almost invariably practitioners of the

?art? of armed robbery ? the easiest, least

subtle form of stealing. Half-orcs typically

lack the patience and subtlety to make good

burglars, are often failures as pickpockets,

and are too self-centered to work well in

groups. That leaves strong-arm tactics as

the most reliable means of making a quick

gold piece on which to survive.

The more intelligent half-orc thief will

almost always take up the role of highwayman,

either alone or as the leader of a small

band of significantly weaker bandits. He

knows that as a half-orc, he won?t easily fit

into city life, where he will be viewed with

constant suspicion and where patrols of

guards are entirely too frequent. He will lie

in wait for merchants and adventurers,

robbing them by force if practical or by the

dark of night if necessary.

Such highwaymen, however, do not make

up the majority of half-orc thieves, though

they are often the most powerful and

longest-lived of their race. The majority of

half-orcs who adopt the thieving profession

are quickly hired as enforcers and strongarm

thugs by crime lords and powerful

guildmasters in urban areas, serving much

the same purpose as the hired gunmen and

goons employed by modern-day organized

crime bosses. That purpose, of course, is to

threaten reluctant clients and customers

with violence unless they do as they?re told

?and to carry out the threats if necessary.

In one respect, half-orcs would seem

unsuited to the status of hireling; their

typical ?me first? attitudes suggest that

they would make unsafe employees at best.

But the masters of half-orc thugs take great

care to retain the loyalty of their staffs.

These measures include regular (and reasonably

good) pay, fairly close supervision,

and active efforts to keep hired enforcers

from using the full range of their thieving

skills. Most significantly, such hirelings are

strongly discouraged from searching for and

removing traps, a practice which decreases

the likelihood that a thug will be able to

make off with his employer?s carefully secured

loot or acquire professional secrets

which could be sold to a rival. If kept on a

short leash, a half-orc thief is almost as

reliable a killer as a genuine assassin.

Very few half-orc thieves remain to join

adventuring parties, and even fewer remain

with such groups for long. A good percentage

are quickly done in by unlooked-for

traps (and, to a half-orc in a dungeon, most

traps are unlooked-for). Most of the others,

once they have identified the most valuable

treasure carried by party members, will

steal the best items and leave their victims

in no condition to pursue. In short, no

matter what the circumstances may be, an

encounter with a half-orc thief is likely to

leave the thief's opponent worse off than he

was before.

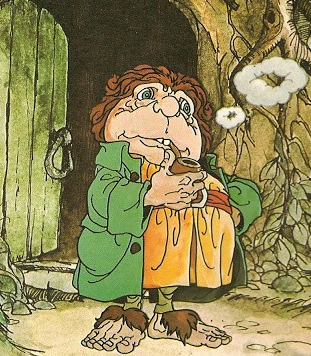

Halflings: another look

The Hobbit Point

of View +

Popular reports have characterized halfling

thieves as sly, avaricious tricksters who

should be trusted only as far as high-level

fighters can throw them. Closer observation

of halfling society, however, reveals that this

portrait is almost entirely without foundation.

In fact, such characters may be among

the most reliable adventuring companions

imaginable.

The sheer greed that so many treasure

seekers associate with halflings is the first

casualty of a serious investigation. Though

halflings do value their comfort, especially

in their own homes and villages, they are

not particularly interested in money, gaudy

jewelry, or even magic. Rather, the possessions

they value are useful as well as attractive

and durable: furniture, good food,

fine

ales and tobaccos, and the like.

While the preceding description applies

chiefly to halflings who stay at home and

lead quiet, peaceful lives, those who take up

the adventuring lifestyle are not very different.

Almost all halfling adventurers belong

to the thief character class; fighters and

clerics tend to stay at home serving and

protecting their villages. The single personality

quirk that distinguishes these travelers

and explorers from other halflings is an

intense, constant curiosity about the world

beyond the hills visible from the parlor

window. Halfling thieves aren?t satisfied

with mere stories about dragons, twothousand-

foot waterfalls, or cities built of

rainbow-colored glass; they want to see all

these things for themselves.

A halfling?s inquisitiveness, however, can

never entirely overwhelm the shy caution

that is the race?s trademark, nor can it keep

them from complaining periodically about

the danger, discomfort, and uncertainty that

go with an adventuring life. As a result,

halflings often go to some length to avoid

encounters with unknown persons and

creatures, making themselves as inconspicuous

as possible until they are sure it is safe

to emerge from their hiding places. And

they are wary of any situation where they

are offered something for nothing; halflings

are shrewd bargainers who know there is

usually a catch to such transactions.

It may be noted that this description of

halfling thieves makes virtually no reference

to stealing or to other skills normally associated

with the thief class. This is not unintentional;

rather, it mirrors the almost

complete lack of attention paid by halflings

to such matters. To a halfling, treasure and

other material rewards for adventuring are

basically irrelevant, and in fact, halflings

have been known to refuse enormous rewards

and turn down chances to collect

magnificent treasures -- such things are

frequently too cumbersome to be easily

transported, and often are not likely to be

very useful once they are dragged home.

This is not to say that halflings lack the

skills possessed by other thieves ? though

it?s a mystery where they acquire them,

since very few of the little folk engage in

locksmithing or metalwork, and no halfling

society yet discovered is host to a thieves?

guild. The difference is in the use to which

halflings employ these talents to protect and

rescue themselves and their associates when

an adventure somehow gets out of control.

As long as the party is proceeding smoothly

toward its goal or destination, a halfling

thief is likely to spend most of his time

admiring the scenery. Only when trouble

starts will he rush to set things right, dart-,

ing bravely (but never foolishly) into combat,

or scurrying to free trapped comrades.

All this is done matter-of-factly and without

undue fuss; any praise heaped on a

halfling?s shoulders afterward will probably

be shrugged off lightly, often with grumbles

that the crisis wasn?t his fault. Such gratitude

is still well deserved. A halfling will

never willingly desert a companion in need,

and may go to truly amazing lengths to

effect a rescue.

Thieves and thieves

It should be clear from the preceding

sketches that the character class labeled

"thief" is by no means as narrowly

specialized

as the name would suggest. Though

many members of the character class are

thieves in the more conventional sense of

the word, just as many are reasonably lawabiding

folk who would be insulted if their

friends and companions accused them of

being criminals. In particular, demi-human

thieves illustrate this point as a result of the

vastly different worldviews held by each of

the races. To put it simply: There are

thieves, and there are thieves ? and then

some. Calling someone a thief in the real

world implies some fairly specific legal and

moral judgments, but saying the same thing

about a character in a game campaign

doesn?t carry the same impact. Further

details are necessary before players can

make judgments about thief characters.

Among those details, the thief's race is one

of the most significant.