| The language of armory | Anatomy of the field | Charges: decoration and identification | The use of arms in gaming | Bibliography |

| Dragon | - | Estelmer |

- | Dragon 53 |

The term “heraldry” is widely used to

denote the study and use of coats of

arms to identify persons, families, or

organizations. The correct term for this is

“armory,” while “heraldry” properly refers

to all the duties of heralds. These

duties included record keeping (especially

of coats of arms), acting as messengers and negotiators, and organizing

events such as tournaments, coronations,

and celebrations. This article is

concerned only with armory and its application

to fantasy role-playing.

The origins of the use of coats of arms

are obscure. In ancient Israel and Rajput

India, badges were used to identify tribes

or people loyal to a prince. The seal

cylinders used in ancient Mesopotamia to

identify persons, American

Indian totems, and some flags are also distant

relatives of armory.

Only Japan and western Europe developed

true feudal systems, and only Japan developed something approaching

the complex European system of armory:

the “mon.” This heraldic badge was

never displayed large enough to be seen

at some distance, like a coat of arms

was

displayed on a shield, but it resembles

a

coat of arms in many respects: It was

used for decoration as well as identification,

it was displayed by troops and retainers as well as by the man entitled

to

bear it, and after several centuries of

use

the privilege to bear the mon was confined

to those legally registered with the

sovereign’s consent.

The purpose of the coat of arms was to

identify at a distance the man carrying

or

wearing the colors. During the Norman

conquest of England and the First Crusade

(both in the eleventh century) coats

of arms did not exist, though a few individuals

might bear an animal figure on a

shield. But as helms improved they covered

more of a man’s face, and armor

also obscured the wearer’s identity as

it

became more complex and covered more

of the wearer’s body. Moreover, the Crusaders,

speaking a dozen different languages and unfamiliar with their new

comrades, needed some simple means

of recognizing one another. It was not

enough to know a man’s nationality;

troops were loyal to individuals, not

to

nations.

Gradually, leaders began to adopt

simple colored patterns to display on

shields, surcoats, and flags to extricate

themselves and their followers from the

anonymity of full armor. Words or letters

would not have served, of course, in a

world of nearly universal illiteracy.

A

large display was necessary in a military

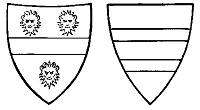

Left: arms of Michael de la Pole, Earl

of

Suffolk; azure, a fess between three

leopards’ faces or. Right: arms of William

Madault, Earl of Warwick; argent, two

bars gules. (See text for an explanation

of the descriptions.)

system dominated by armored cavalry,

for it was vital to know whether a man

was friend or foe before one charged.

Arms also served as patterns on seals

and signet rings. In some cases, such

as

the Great Seal of England, any document

not stamped with the proper seal

had no validity or force in law.

At first the patterns adopted were simple,

with ease of recognition uppermost

in mind. But as more knights adopted

arms, more elaborate patterns were

needed to avoid duplication. Nevertheless,

duplication could occur, on at least

one occasion requiring the personal intervention

of the King of England to determine who rightfully bore the arms.

It became evident that some record of

who was entitled to which arms would

help keep the peace. At this same time

(fourteenth century), sovereigns began

to grant arms to those deemed worthy,

and finally it became illegal to adopt

a

coat of arms without consent of the sovereign.

Military leaders usually adopted

or obtained coats of arms, and so the

holders of arms were usually nobility.

In parts of Europe, only those who

could prove that all 16 of their greatgreat-grandparents

were entitled to bear

arms (“seize quartiers”) could themselves

bear arms. But in other areas,

even certain peasants possessed coats

of arms. Clergy also became associated

with arms. The abbot of a monastery or

bishop of a province carried the arms

of

the body he represented. And though

clergy were not supposed to fight, many

did so and consequently deserved arms

to identify themselves and their retainers.

Military orders (such as the Knights

Templars) and guilds also obtained arms.

Before some of the rules and conventions

of armory are described, it should

be pointed out how armory may be incorporated

into role-playing. First, the

DM must decide where a country lies in

the progression from assumed arms to

granted arms. If the country is lawful

or

neutral, loyal and obedient to a single

sovereign lord, then the lord may well

have begun to grant arms while prohibiting

the assumption of arms without his

permission.

In a less orderly country, or an area

ruled by a lord who owes nominal allegiance

to a higher sovereign, powerful

individuals may assume arms without

fear of prosecution from the ruler, though

they still must beware of a dispute with

someone who already has similar arms.

Such a dispute might be settled by battle

or in a High Court.

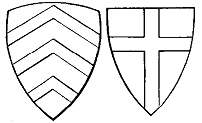

Left: arms of Gilbert de Clare, Earl

of

Gloucester and Hertford; or, three

chevrons gules.

Right: arms of Roger le Bigod, Earl

of Norfolk; or, a cross gules.

most likely to have arms, and a man with

many retainers, even a merchant or other

non-adventurer, is more likely to require arms than is a lone magic-user

or

thief. Possession of arms is considered

to be a prerogative of a gentleman, so

a

thief or other person living on the fringes

of acceptable society is not likely to

bear

arms.

In chaotic areas, duplication of arms

might be common, even deliberate. Many

leaders might not bear arms at all, preferring

some other method of identification such as a distinctive style of armor

or helmet.

In any area where infantry rather than

cavalry dominates the armed forces,

coats of arms could be less commonly

used. Of course, flags can incorporate

coats of arms, but they can also represent

nations rather than individual lords.

Where only the arms are used for identification,

it is possible to impersonate an

individual or pretend to be a group of

retainers of some lord. There are many

opportunities to make armory and heraldry

a part of the game if the DM is

willing to do the necessary groundwork.

The descriptions and definitions below

are merely an introduction; in order to

understand armory better, the reader

should consult reference works such as

those listed in the bibliography.

An “achievement of arms” or “armorial

bearings” consists of several elements

—the crest, helm, supporters, mantling,

and shield. But for the original purpose

(identification) only a patterned shield

was used, and this is the only element

this article will describe.

Armory uses a special language, descended

from French and Old English, to

describe the pattern of arms. While the

details can become complex, the objective

was to describe the pattern briefly,

elegantly, and uniquely, however strange

the words may sound today. As the elements

of the patterns are discussed,

some of the words needed to blazon, or

describe, the arms will be introduced.

Only nine contrasting tinctures

are

used on a shield, divided into five colors,

two metals, and two furs.

For practical

use, the metals can be considered two

additional colors, while the furs are

patterns of two other tinctures. The colors

are black (sable), red (gules),

blue

(azure), green (vert), and

purple (purpure). In England, orange-brown (tenne)

and sanguine (murry) are occasionally

used, but they are regarded as tainted

colors indicating illegitimacy

or other

fault or flaw in the bearer’s ancestry.

The metals are gold (or), usually

represented as yellow, and silver (argent),

usually shown as white.

The rarely used furs are ermine

and

vair. Ermine is an argent background

covered by regularly spaced black marks,

which consist of an arrowhead surmounted

by three small dots, one just

above the point and one to either side

and slightly lower. This “fur” derives

from the fur of the arctic stoat (ermine),

which, used as the lining of cloaks, became

a symbol of rank and office. Vair

(from an unusual squirrel fur) is represented

by rows of bell shapes, the argent

upside down and the other tincture (usually

azure) right side up so that the two

rows fit together alternately; four sets

cover the shield.

The first element of the blazon

(description) is the tincture of the shield as a

whole, the field. Occasionally

the field

may be a pattern of small objects, similar

in effect to one of the furs. Next comes

the charge, describing the object

placed

over the field. Sometimes a party field

(a

field of two tinctures used in roughly

equal amounts) is used without a basic

charge.

The field and charge alone are enough

to construct many distinctive patterns,

but most arms include elaborations of

the charge. These include heraldic animals,

crosses, towers, abstract shapes,

common beasts — virtually anything the

originator of the arms desires.

Arms may be differenced and marshalled

as well, to indicate marriage alliances, sons, bastardy, and the like.

Differencing and marshalling can be a complicated subject, and should be

pursued

further only by those readers who are

sufficiently interested.

Anatomy of the

field

The rule of armory is that no color

should be placed on a color and no metal

on a metal. For example, a gold charge

may be placed on a blue background (or

vice versa), but a gold charge should

not

Armorial bearings of John Comber, Esq.:

Arms described as quarterly, 1 and

4, or,

a fess dancette’ gules, between three

estoiles sable; 2 and 3, argent, a chevron

sable, between three thorntrees proper.

be placed on a silver background. This

rule was adopted to heighten contrast

and improve visibility at a distance.

It is

done, however, and whether the rule

should be enforced (and how) must be

left to each DM.

The parts of the field are named in the

language of armory as follows. The left

side or flank as one looks at the

shield is

the dexter, the right side the

sinister.

(These latter terms derive from the Latin

for right and left, respectively, but

this is

from the viewpoint of someone behind

the shield, the one holding it.)

The chief is the top third of the

field;

the fess is the middle third; and

the base

is the bottom third. The blazon for a

red

shield with a white top third, then, is

“gules, a chief argent.”

The parts of the shield which comprise

the basic charges are also known as ordinaries.

There are other ordinaries besides the chief, fess and base which do

not so easily correspond to parts of the

field. A pale is a broad vertical

line running from the top to bottom of the shield

through the middle. A chevron is

an inverted “V” not quite reaching the top of

the shield, but entering the chief at

its

point. The bend is a diagonal bar

running from upper left to lower right. A

saltire is a narrower bend plus

a bend

sinister — that is, a bend running from

lower left to upper right; the entire

design looks like an “X.”.

The lines followed by the ordinaries

may be used to divide the shield per

party. For example, per party saltire (or just

per saltire) is a shield divided into

four

quarters by an “X.” A shield divided by

a

cross would be quarterly. There

are many

variations on these basic patterns, such

as bendy (several narrow bends

parallel

to each other), a chief indented

(with a

sawtooth-like boundary rather than a

straight-line boundary), or a cross wavy

(with a wavy rather than a straight outline),

or bordure (a narrow border all

around the field).

Thus, a shield “per pale gules and

azure a chevron or, a bordure sable”

is

red on the left, blue on the right, with

an

inverted yellow V over the colors of the

field and a black border around the

shield. A book

of heraldry will describe

many other combinations.

Charges: decoration and identification

The primary charges on the field can

be virtually anything. There are conventional

drawings (and special names) for

the more common charges, as well as a

language for describing how the charge

is arranged when there can be doubt. For

example, it is not enough to say where

an

animal is on the shield; its facing and

attitude must also be stated to avoid

ambiguity.

When a man assumed arms, he often

chose charges symbolic of himself or his

family. The less solemn might make a

play on words, such as the family of Catt,

Catton, or Keats using a cat as a charge.

William Shakespeare’s arms showed a

hand grasping several spears.

An animal

related to the location or nature of his

estates, such as a fish for an islanddwelling

knight, might be preferred.

The more serious or idealistic might

choose symbols to emphasize their

courage or good fortune. Thus the lion,

symbol of valor, was a favorite charge,

and the dragon likewise. Religious piety

could be expressed in the arms. The

Christian (Latin) cross is the classic

means, but a special cross of Calvary,

angels, or other religious symbols might

be used.

A list of some types of popular charges

includes: divine beings, humans, lions,

deer (stag, hind, etc.), felines (cat,

panther, Bengal tiger, etc.), bears, elephants,

camels, birds, fish, insects, monster

(dragons, wyverns, unicorns, griffons,

etc.), celestial objects (sun, moon, stars

[“etoiles”], clouds), trees, plants,

flowers

(fleur-de-lis, rose, etc.), and certain

inanimate objects (castle, five-pointed star

[“mullet”], caltrop, whirlpool,

galley,

sword). When a charge is presented in

its

natural color, the blazon is said to be

“proper.”

Four-legged animals are frequently

used as charges. The common attitudes

are defined below. (Generally, the tail

is

erect.)

Rampant (as “a lion rampant”): Animal

stands on one hind leg with three legs

in

the air at different angles.

Passant: Three legs are on the ground

with the dexter foreleg raised to head

height. The tail curves over the back.

Salient: Leaping, but with both

hind

legs still on the ground. (The “ground”

the animal stands on is never shown, of

course.)

Statant: As passant, but with all

four

legs on the ground.

Sejant: Seated on hindquarters with

all

legs on the ground. (Sejant erect: Front

paws are high in the air at different

angles.)

Couchant: Legs and belly are on

the

ground but head and tail are held high,

the tail first passing between the legs.

Dormant: As couchant, but with head

down and tail on the ground —sleeping,

in effect.

Lion statant (left), lion passant guardant

(top right), and lion passant regardant

(bottom right).

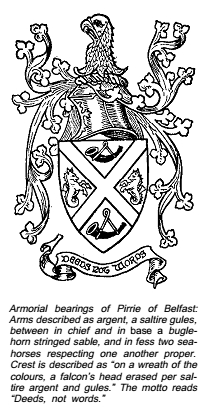

Armorial bearings of Pirrie of Belfast:

Arms described as argent, a saltire

gules,

between in chief and in base a buglehorn

stringed sable, and in fess two seahorses respecting one another proper.

Crest is described as “on a wreath

of the

colours, a falcon’s head erased per

saltire argent and gules.” The motto reads

“Deeds, not words.”

In all positions the animal faces to the

dexter. Other terms (below) describe the

head position. Unless one of these is

used, the head also faces to the dexter.

Guardant: Head faces the person

looking at the shield.

Reguardant: Head looks backward

over the animal’s shoulder.

An animal “sinister” (as in “Lion passant

guardant sinister”) faces the right

side of the shield as we look at it.

Blazoning is fairly simple once you

pick up some of the vocabulary. After

reading just a few paragraphs, you know

what that strange concoction, “a lion

rampant guardant or,” means. Boutell’s

Heraldry (see bibiliography)

gives descriptions of all the terms you’ll ever

want to look up.

The use of arms in

gaming

There are a myriad of ways for the DM

to incorporate the use of armory in the

campaign. Three general suggestions

are given below, and should cause other

possibilities to come to mind.

First, a player who possesses arms

hears of or meets a non-player

character

with similar arms. Is this an honest mistake,

or is the NPC trying to deceive others? The player character can hardly

ignore the situation — he’ll have to investigate further.

Second, some non-player character

accuses a player character of stealing

the accuser’s armorial bearings. A challenge

to combat or an appeal to the high

court may result. The accusation may be

only a means to some dark end.

Third, in order to accomplish some

goal the player desires — for example,

marriage to a noble’s daughter, he must

earn arms from the King. This means he

must visit the King (a wilderness adventure

in itself) to discover what he can do

to earn arms, and then he’ll have to accomplish

that task.

Bibliography

Dozens of books about heraldry have

been published in the past twenty years.

In general, one is better off avoiding

the

older books, especially those of the last

century.

J. P. Brooke-Little, ed., Boutell’s

Heraldry

L. G. Pine, Teach Yourself Heraldry

Charles MacKinnion, Observers Book

of Heraldry

(Editor’s note: Illustrations for this

article, and the descriptions accompanying those illustrations, were taken

from

“The Art of Heraldry” by Arthur

Charles

Fox-Davies, published in 1976 by Arno

Press, New York. Readers are referred

to

that book or a similar reference work

for

definitions of terms mentioned in the

captions which are not included in

the

author’s text. There are far too many

specific terms used in armory and heraldry

for an article of this scope to be

able to cover them all. The meaning

of

many of the terms can be figured out

by

matching the elements of a description

with its accompanying picture.)

Of course, the best place to start is the

encyclopedia. Most heraldry books will

tell you far more than you’ll ever want

to

know; an encyclopedia gives you a more

manageable dose.

(Editor’s note: Examples of the use

of

heraldry in fantasy role-playing may

be

found in THE WORLD OF GREYHAWK™

fantasy world setting by Gary Gygax

[produced by TSR Hobbies, Inc.].

The front and back covers of this playing

aid are crowded with full-color arms

for the various nations described within.

Some traditional heraldic rules such

as

color combinations are broken, but

this

is in the name of artistic license

to produce a better-looking product.

Many of the arms were designed to

correspond to the factions they represented:

The arms of the Free City of

Greyhawk have a broken chain over a

wailed city; the Orcs of the Pomarj

have a

grinning skull; the Hold of Stonefist

—

you guessed it, a stone fist.

A total of 78 arms are depicted, and

there is a brief discussion on orders

of

knighthood and how they may conflict

and compete in a fantasy world setting.)

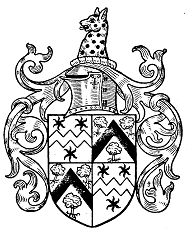

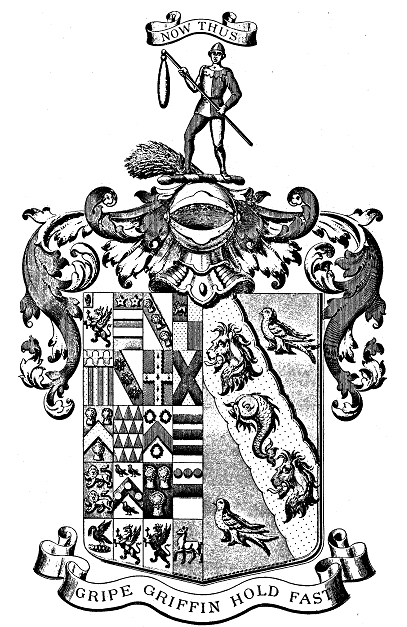

This reproduction of the armorial bearings

of Sir Humphrey Francis de Trafford

illustrates how complex an armory design

could be. The elements of the arms are

described as follows: Quarterly of

twenty, 1. argent, a griffin segreant gules; 2. argent,

two bears, and in chief two mullets

pierced azure; 3. argent, on a bend azure, three

garbs proper; 4. quarterly, gules and

or, in the first quarter a lion passant argent; 5.

paly of six argent and gules, a chief

vaire; 6. argent, on a bend gules, three escarbuncles sable; 7. vert, a

cross engrailed ermine; 8. or, a saltire sable; 9. azure, a chevron

argent, between three garbs proper;

10. bendy barry gules and argent; 11. argent, a

chevron gules, between three chaplets;

12. argent, three bars sable; 13. gules, two

lions passant guardant in pale argent;

14. argent, on a chevron quarterly gules and

sable, between three birds of the second

as many bezants; 15. argent, three garbs

proper, banded or; 16. argent, a fess

sable, in chief three torteaux; 17. argent on a child

proper, wrapped in swaddling clothes

gules, and banded or, an eagle sable; 18. argent,

a griffin segreant azure; 19. argent,

a griffin segreant sable, ducally crowned or; 20.

azure, a hind trippant argent, and

impaling the arms of Franklin, namely: azure, on a

bend invected between two martlets

or, a dolphin naiant between two lions’ heads

erased of the field.

Heraldry hints

To the editor:

In the September 1981 issue of DRAGON

magazine, Lewis Pulsipher has written a generally

good article giving a brief introduction

to armory. (I tend to disagree with him that

“heraldry” should not be used, since the principal

duty of heralds has been to keep coats of

arms straight [“Or, a fess checky argent and

azure, within a tessure fleury-counterfleury

gules? That’s Sir Robert Stuart, uncle to the

King of Scotland, my lord.“], and anyway, heraldry

is, rightly or wrongly, the generally accepted

term.) There are a couple of things I

would like to add.

First, while the fact that there are two different

kinds of tinctures, the metals and the colors,

is mentioned, Mr. Pulsipher gives the

impression that there is no real difference between

them. There is a difference, and while it

is not very important in an AD&D

game, where

you are working with figures a couple of feet

away, it is important on a battlefield. One of

the first rules of heraldry is: Do not put a metal

on a metal or a color on a color. The reason is

that such a combination does not show up

very well at a distance. (Try reading, for example,

red printing on blue paper.)

There are other furs than just ermine and

vair. (Incidentally, the word vair [a squirrel

skin] is responsible for one of the great misconceptions

in literature. When Charles Perrault

wrote Cinderella, he described her footgear

as “peds du vair,” or squirrel-skin slippers.

In the English translation, this became

“peds du verre” — glass slippers.) The other

ermine (black tails on a white background;

note the color-on-metal combination) based

furs include ermines (also called contre-ermine),

white tails on black; erminois, black

tails on gold; and pean, gold tails on black.

The vair variants include different shapes and

arrangements of the bells, and other tinctures

than the standard blue and white.

There are many different charges that one

can put on a shield (the term “coat of arms”

refers specifically to a surcoat worn over the

armor, but the usual depiction of a coat of

arms is on a shield), and many variations on a

theme — Fox-Davies, I believe, has examples

of over two dozen different kinds of crosses.

In addition to the books Mr. Pulsipher mentions,

I also recommend Simple Heralrdy by

Ian Montcrieffe and Don Pottinger. The main

advantage of this book is that all the illustrations

are in color.

John A. Hobson

Bolingbrook, III

(Dragon #56)