| Strength | Constitution | Dexterity | Intelligence | Wisdom |

| Charisma | - | - | - | Conclusion |

| Dragon 107 | - | - | - | Dragon |

Six personal characteristics are given to

each character in the AD&D® game:

strength, intelligence, wisdom, dexterity,

constitution, and charisma. Of these,

strength is the most physically obvious

attribute. Strength is the basic muscular

ability to lift objects, to throw, to run,

jump, swim, and to affect the universe

directly. The pen may be mightier than the

sword, but the pen (intelligence) does its

work indirectly. The sword (strength) is

direct and physical. Constitution is also

physical, but less energetically so: if

strength is the sword, then constitution

must be the suit of personal armor. Dexterity

is the skill to use the bodily weapons,

and intelligence is the skill to use them

effectively. Wisdom represents the skill to

use them only when they are needed (and to

know what that need might be), and charisma

is the diplomacy to find ways other

than weaponry to settle matters. This article

deals with the six characteristics in this

order, progressing from the most material to

the least. More is known about strength

than is about charisma, just as more is

known about engineering than about psychology.

The study of each is inherently

interesting.

For the analysis of the physical characteristics

? strength, constitution, and dexterity

? I?ve relied on a volume about sports

medicine.

(The Athlete's Guide to Sports Medicine by Ellington Darden,

Ph.D.;

1981: Contemporary Books, Chicago.)

More has been published about sports

medicine than about the medical aspects of

swordfighting, even though the two pastimes

are not totally dissimilar.

Strength

The muscles of the human body are

composed of bundles of muscle fibers, giving

muscles their familiar ?ropy? look. The

fibers of the voluntary muscles can contract

and relax, pulling an arm or leg into specific

position. Muscles do not, in general

push, but nearly always pull, and this tension

works to draw the limbs into bent or

straightened positions. The muscles are

usually paired: while one muscle works to

bend a knee, for example, its partner relaxes.

When the knee is to be straightened,

another muscle (or set of muscles) pulls

along the outside of the knee to straighten

it, while the bending muscles relax. The

rigid bones of the body provide the levers

upon which the muscles act. Ligaments and

tendons connect the muscles to the bones,

anchoring them firmly yet flexibly.

The result of the flexing and relaxing of

the voluntary muscles is the voluntary

action of a healthy body: a run, a leap, a

swing, and a splash. A person?s strength is a

measure of his or her muscular power, and

is reflected in speed, lifting ability, throwing

ability, and jumping range. Strength is also

partially related to a person?s capacity to

absorb damage or resist pain, and to his

endurance.

Women are distinctly less strong than

men, and the reasons for this are partly

biological and partly sociological. In virtually

no part of history before the present

were women encouraged to exercise. A

whole collection of myths arose to suggest

that exercise was bad for women, and that

their delicate bodies weren?t equipped to

handle the rigors of a developed physique.

Beyond these easily-debunked tales lies the

biological fact that women do not produce

some of the chemical hormones that cause

the huge bulging muscles seen on bodybuilding

men. But muscle mass is not the

same thing as strength; women who exercise

regularly can build up substantial strength.

World records for hurdle races, for example,

indicate that the difference between a highly

conditioned male runner and an equally

well-conditioned female runner is about ten

per cent of the race time. If a man can run

a race in 100 seconds, a woman can probably

run it in 110 seconds. The same relation

is true in swimming and throwing events.

There is a tremendous variation in people,

from the very fittest to the very flabbiest:

the difference between the average woman

and the average man in strength is far less

than the difference between the strongest and

the weakest of either sex.

The differences between men and women

nearly vanishes when humans are compared

to some of the animals. Even small monkeys

are stronger than large people. A gorilla,

although not much larger than a human, is

massively more strong, being able to outfight

the human by a handy four-to-one

ratio. Even a small housecat can put up a

struggle against a human (even discounting

the use of the cat?s claws and teeth), although

the ratio of the weights of a man and

a cat is close to twenty to one. Why is it that

animals are stronger, per pound of muscle,

than humans are?

There are two answers to this. Humans

are largely neotenous, which is to say that

we carry youthful or infantile features of

our bodies into adulthood. Adult humans

still have childlike bodies, when compared

to other animals. We lack most of our body

hair, we have high foreheads and large eyes,

we have alert, adaptive, and playful minds,

and we have underdeveloped muscles. Since

all of the other characteristics listed are

advantageous, the small disadvantage of our

relative weakness is compensated for. The

other answer to animals? greater strength is,

that animals use all of their strength, all at

once, when fighting or struggling, whereas

humans don?t have many opportunities to

need to use the full resources of their

bodies. (This is, of course, fortunate for us.)

When a cat, dog, or ape attacks, the attack

is all-out, holding nothing is reserve. Humans

favor a more tentative attack, prodding

and jabbing, looking for weaknesses.

When a human undertakes exercises to

enhance his or her strength, the regimen

should be thorough and careful. The risks

from over-exercising can be worse than the

risks of being out of shape. Muscles are

built up by being injured ? very, very

slightly! ? and then healing, and this healing

requires forty-eight to seventy-two

hours. Thus a person exercising to increase

strength should exercise hard, pushing until

feeling tired and sore; but no farther, and

then resting for a day. It is true, as the

advertisement says, that if there?s no pain,

there?s no gain. But care must be taken not

to take the pain too far. If ten push-ups

causes sore arms, then twelve push-ups is a

good daily score, increasing over time.

Fifteen, however, would be too many. If a

runner is out of breath after jogging for ten

minutes, he should consider jogging on for

another minute or two, and the pain in the

legs is an indication of future musclebuilding.

Going on for another ten minutes,

however, would be excessive. People who

are exercising to increase their strength will

notice that it can be easily increased, and

they will learn to tell the difference between

being tired and being hurt. The former is

necessary, the latter to be avoided.

Alas for the would-be bodybuilder in

AD&D gaming, the number rolled on the

characteristics dice for strength, like that

rolled for the other characteristics, is fixed

once rolled. Some referees, however, might

allow characters who undergo training to

increase strength and constitution, only, one

or maybe two points through training. If so,

then if the training is discontinued, for any

reason, the characteristics will drop to their

normal (rolled) values.

Constitution

A person?s constitution is a measure of

his or her overall health, endurance, and

vigor. Someone with a high constitution will

have fewer colds and headaches, and will

probably live to an older age. Most diseases

are deterred by a good constitution, although

many ? including the highly virulent

viruses, cancer, and nervous system

disorders ? are not. The three most obvious

assets of a good constitution are a

strong heart, healthy lungs, and a good

muscle tone. The heart is the body?s primary

means of limiting people?s activity:

when the heart is too tired to continue, the

person gets tired and will generally be unable

to continue. Although when we cannot

continue running or climbing we usually

say that we?re out of breath, the fact is that

the heart has simply stepped its demands for

oxygen so far up that the lungs cannot

supply it and the muscles. The body is

exhausted, and the runner or climber can

only sit and wait. This is a safety mechanism.

One sports doctor has said that it is

impossible to overstrain the heart, since the

heart controls the amount of strain it will

allow the body to put upon it. Through

diligent hard work, it is probably possible

for an athlete to damage his or her heart by

jogging on and refusing to heed the body?s

danger signals. This, however, is something

no athlete would choose to do.

When muscles are exerted, they begin to

build up fatigue poisons, mostly lactic acid,

in their tissues. Probably everyone is familiar

with having stiff, sore muscles after a

workout; this is because the fatigue poisons

require time to be metabolized. This pain

and stiffness is also a sign that the muscles

have been stressed, that they are healing,

and that the exercise is having its intended

effect. Exercises to build up stamina and

endurance are different from exercises to

build up strength, however. lb build up

strength, exercise periods should be short

and periodic: twenty push-ups followed by a

short break, then repeat. To build up constitution,

exercise should be continuous, but

at a lower level of activity. Long walks, or

jogging, are ideal for building up constitution.

The important thing is to have the

heart beating at a steady, high rate, and the

blood flowing through the major veins and

arteries.

Here; too, there is a sex difference.

Women tend to have better constitution

than men, if all other factors are equal. This

is not something that can be observed in the

general population, for it is still true that

young girls do not learn to exercise to the

degree that young boys do. In America,

women and men are approximately equal in

constitution, but the natural advantage is

on the side of the women.

Dexterity

The AD&D game uses dexterity as an

overall characteristic, embracing manual

dexterity, coordination, and agility. But all

of these are quite different. Manual dexterity

is the deftness of the wrists and hands,

and shows up in such activities as throwing

darts, painting, sewing, and of course typing.

By correlating messages from the eyes

and hands, people can become capable of

amazing feats of dexterity. The key is

endless hours of repetitious practice. With

practice, nearly anyone can become blindly

adept at video games, for example, or at

typing, sewing, or playing the guitar. The

motions need to be learned through repetition,

until it can almost be said that the

fingers know the correct moves better than

the mind does. The only limits to manual

dexterity are the time spent in practice, and

any physical or neurological limitations of

an individual?s physique. If a person?s body

is healthy and he is not suffering from any

nervous system disorders, then even if he is

the clumsiest and most awkward of persons,

he can train his dexterity upward.

Overall physical coordination is slightly

different. It is a measure of the quickness of

the body?s reflexes, and of the overall ability

to act smoothly. Coordination comes into

play when shooting a basketball, swinging

at a pitched baseball, kicking at a planted

football, or juggling.

Researchers in sports medicine have

discovered that the concept of ?general

skills? such as overall dexterity or overall

coordination tend to break down into specific

skills. In fact, very slight variations in

the skill learned can have disastrous effects

upon the application of the skill. If a tennis

player switches to an unfamiliar racket, his

or her overall playing ability will initially

deteriorate. Ultimately, it seems that people

don?t have one sort of coordination; but

have several coordinations relative to different

tasks. We know that being good at

typing gives no guarantee of being good at

playing the piano, but it might be surprising

to know that playing the piano well is

no guarantee of being able to play the harpsichord

well, since some of the muscle interplay

is slightly different. For many years it

was thought that teaching students to play

tennis would carry a benefit over into driving

a car. The fact is that coordination

breaks down into skill-related categories

which are very different.

Agility is the overall flexibility and quickness

of the body. One who is highly agile

might be a better climber, swimmer, runner,

and be better at dodging. The ability to

walk along the balance beam is an agility

skill. Again, this breaks down into subcategories,

and there are many different

agilities inherent in one person. Even the

sense of balance is not a general skill: one

who is good at walking a balance beam with

his feet lengthwise has no assurance of being

good at walking along it with his feet held

crosswise. There is very little common skill

in balancing. The same is true for running;

only a few of the skills involved in running

carry over from one type of run to another,

even when both runs are of the same general

distance and duration.

Skills are improved by practice. Dexterity,

coordination, and agility can all be

learned. One aspect of skills training is

called skill transference, and transference

comes in three varieties: positive, negative,

and indifferent transfer. If a fencer learns to

fence with an epee, this skill has virtually

nothing to do with learning to fence with a

saber; the skill transfer is indifferent. Someone

learning to perform a skill needs to

practice with that skill, in precise detail,

before the practice will have a beneficial

effect. Playing tennis against a backboard

has only an indifferent transfer of skill

toward playing tennis against an opponent.

Negative transfer occurs when two skills are

close to one another, but are not identical.

Someone who learns to shoot a thirty-pound

bow will be extremely frustrated by a thirtyone-

pound bow. Practice with a mace wills

not give skill in the use of a sword, and

practice with one sword will not guarantee

skill in the use of another sword. One must

practice the skills that are to be learned.

Anyone familiar with the ongoing debate

about I.Q. tests will know that the nature of

intelligence is problematic. In the nineteenth

century, scientists developed the

notion that intelligence was related to brain

size, and rigorous measurements were made

of the volume of the braincases of skull

specimens. In the mid-twentieth century,

the notion of a written intelligence test was

put forward, and received enthusiastically

by the scientific community. Flaws became

immediately obvious. To begin with, how

can an intelligence test in the form of a

paper-and-pencil quiz measure the intelligence

of someone who cannot read? According

to most of the theorists in the 1930s

and 1940s, intelligence was an innate, fixed

thing, inherent in the individual. In the

1950s and 1960s, a question arose about the

cultural bias of the most common tests.

Questions could be seen to be reflective of

the ethics and values of white, middle-class,

suburban men (by no coincidence, the very

group of people who had the most influence

in the design of the tests). Finally, the overreaching

question of the innateness of intelligence

arose: can intelligence be learned, or

is it something with which a child is born?

The ?nature versus nurture? issue is a

heated one to this day. For a more detailed

examination of the issue of I.Q. tests than

can be presented here, one book in particular,

The Mismeasure of Man, by Stephen

Jay Could (W.W. Norton and Company,

New York: 1981) is highly recommended.

Some common-sense observations are still

possible. Intelligence can depend on such

factors as health, the proper amount of

sleep, mental health, and surroundings.

Consider someone taking an I.Q. test in a

crowded room full of noisy people, while

suffering

from a cold, while having gotten

only three hours of sleep in the past fortyeight

hours, and while extremely worried

about the results of the test. One of the

many contributing factors to performance

on an I.Q. test is confidence. If the subject

feels confident and hopeful, he will do better

on the test. If the subject feels desperate,

worried, hopeless, or merely anxious about

the test, the results will not be as good. This

is known as the ?self-fulfilling prophecy,?

and suggests that a positive attitude may be

a strong part of appearing intelligent.

INT, in the real, uncontrolled world,

is largely a matter of appearance. We

might say that a man is "sharp as a whip",

or "very bright" if he is the first to notice

an error, the quickest to add up a column of figures,

or the one who comes up with the most clever wisecrack.

People are seen to be intelligent when they are observant,

methodical, or articulate.

Of these, being observant is perhaps the <compare to: Perception>

most readily learnable habit. People who

see what is actually right before their eyes

are in the minority. We fail to notice signs

and we tend to overlook even the most

obvious things, especially when we?re look-

for them. The joke about the person

failing to find his glasses because they are

pushed up on his forehead is a true one, as I

can vouch personally. So, quickly: What is

the license plate number of your family car?

What time of day does the daily newspaper

arrive? How often do you hear the songs of

birds or chirping crickets where you live?

Being observant is not simply a matter of

counting how many stairs there are in a

given staircase. I?m a compulsive stepcounter,

and yet I couldn?t tell you how

many trees there are in my front yard.

Being observant is, instead, a matter of

seeing the important things, at the time

they're important. Clearly an observant

person will be a better driver, and a poor

driver will be seen as a stupid driver, Seeing,

registering, and cataloging the items in

your field of vision is one important step

toward appearing intelligent.

Clear thinking is another. We all rationalize,

every day of our lives. An intelligent

person will stop, every now and then, and

review his assumptions about the way the

world works. Intelligence means reasoning

from cause to effect, or from effect to cause,

along logical paths. It is generally considered

stupidity to try to fit the facts to your

prejudices. For example, despite the thousands

of studies showing that seat-belts in

cars save lives, we still hear people saying,

over and over, "I'd rather be thrown clear

of a collision than crushed in it." The stupidity

of this idea is most evident when it is

examined closely. The people who say this

are doing no reasoning, and indeed are not

thinking the matter through from facts to

conclusions. Instead, they are trying to

justify their own unwillingness to fasten

their seat-belts. Intelligence is partly a

measure of the ability to react to the facts,

and to act in accordance with them. An

intelligent person will take the extra moment

to buckle up, knowing that it increases

his chances of surviving.

Intelligence can also be examined from

the point of view of learned tasks, or from

visual perception. The human brain is

divided into two hemispheres, each of which

controls different aspects of thought. The

left brain, in most people, governs verbal

reasoning, language skills, and logic. The

right brain governs such things as the perception

of visual relationships, music, and

the appreciation of artistic beauty. It has

been determined that most people are

stronger in one hemisphere of their brains

than in the other; thus, we find people who

are highly adept at language skills, while

others are skilled at art and music. In these

cases, although someone might have a head

start in one of these areas, the specialization

is more a matter of an advantage than a

disadvantage. For a left-brain-dominant

person to learn right-brain skills will be

more difficult, but it can be done. Practice,

as always, is the primary key to learning

any new skill.

Wisdom

Wisdom is perhaps the characteristic least

susceptible to improvement. Wisdom, it

would seem, is innate, a fundamental part

of an individual. It is different from intelligence:

you can have intelligent fools, as well

as people who are wise, yet ignorant. Wisdom

would seem to be related to strength of

willpower, to a degree. People can increase

their strength, but only if they have the

wisdom to exercise regularly. It is horribly

easy to skip one day of exercises, on any

excuse. It is easy for a student to skip a day

of class, for an employee to skip a day of

work, and for nearly anyone to delay things

that are necessary. Wisdom is the ability to

say, ?Well, it?s got to be done, so I might as

well do it today.? Wisdom is the subject of

advice of many popular aphorisms: ?Never

put off till tomorrow what you could do

today.? ?The more haste, the less speed.?

?Never be penny-wise and pound-foolish.?

?He who hesitates is lost.?

One?s intelligence can help him understand

these items of advice, but only one?s

wisdom can allow him to follow them at the

correct time. For example, it is said both

that ?He who hesitates is lost,? and ?Look

before you leap.? How does one choose?

When going swimming in a new creek, it is

far better to look at the depth and temperature

of the water before leaping in. When a

runaway garbage truck has lost its brakes

and is bearing down on you, hesitating

might be disastrous.

Wisdom, ultimately, can only be learned

from experience. There are no short cuts to

wisdom, other than to live an interesting

life. I strongly recommend that everyone go

out and make their mistakes, utter their

blunders, goof up, foul up, and choke up,

using intelligence as much as possible, in

order to learn wisdom. Errors teach us

more about life than successes do: an unfortunate,

but true, rule of life.

Adults are invariably more wise than

children, and wisdom is highly correlated

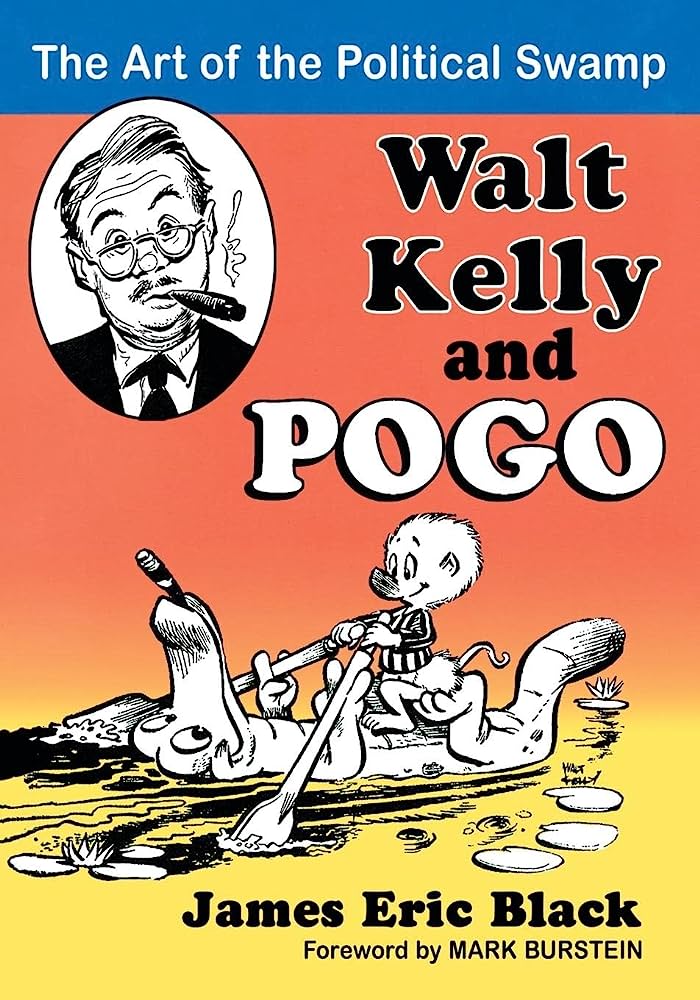

with age. Walt Kelly once said, in his Pogo

comic strip, that being adult is largely a

matter of looking back and not counting

your mistakes. The mistakes, then, will

have taught you their lessons.

Charisma

?Cleanliness is next to godliness.? With

that simple truth, some advertising and

soap companies have tried to put forward

the theory that charisma follows from using

the right mouthwash, detergent, shampoo,

and deodorant. The notion has some basis

in truth -- we are sometimes judged by our

sweat -- but far more often, charisma and

popularity are measures of voice and stance.

Charisma can be studied in the ways of

public speaking. If you can speak to an

audience and hold their attention, then you

have substantial charisma. One study

(which I am unable to cite properly) suggested

that when an audience listens to a

speaker, they judge him according to the

following formula: 80% by his tone of

voice, 15% by his posture, his gestures, and

his expression, and 5% by the actual content

of the words. If this is true (and I,

personally, have a few doubts about the

percentages listed), then charisma would

seem to be a matter of being charismatic,

or, less paradoxically, of being smooth,

suave, positive, persuasive, gentle, and

sincere.

The typical series of conflicting advice

applies: speak up, but not too loudly. Be

firm, but not too aggressive. Use some

humor, but don?t do a stand-up-comedian?s

routine. Maintain eye contact, but don?t

glare. Introduce pauses into your speech,

but never allow dead time to build up into a

long silence. One could go quietly insane

trying to follow all of these items of advice,

when, in fact, speaking before an audience

must be a natural, comfortable thing to do.

One young woman I know exemplifies

another aspect of charisma: leadership. She

has the ability to spearhead a group through

the entire duration of a lengthy, difficult

project. She can run a science fiction convention,

with all of the hassle and infighting

that that entails. I, frankly, haven?t any real

idea of how she does this. I couldn?t do it.

She has the knack of soothing the ruffled

tempers and easing the injured egos of all of

the people involved. When disputes flare up

? and they always do ? she can arbitrate,

finding the optimum solution that leaves

everyone satisfied, if not happy. Does she

ever lose her own temper? Certainly, yet

never in such a way as to alienate the people

she leads. Does she ever stumble, committing

goof-ups or gaffes? Yes, of course. She

also recovers from them. She is about to put

on her eighth semi-annual small convention,

and has enlisted the enthusiastic support

of an entire crew of volunteers. I?ll be

in there helping, and not quite knowing

why. A good leader brings out quality and

effort from a group, often more than they

know they have. For this reason, a group of

skilled and enthusiastic people (or even

hangers-on and detail chiselers like myself)

follow such a leader, respecting her for the

final success of the job.

Since not one person in a hundred is such

a leader, the rest of us must be satisfied with

lesser tasks of charisma. How many enemies

do you have? When was the last time

you made a peace overture to someone you

don?t like? How often do you participate in

spreading gossip? How often do you find

yourself shouting, swearing, or using rude

gestures?

Charisma, to a degree, can be improved

simply by being nice. Nice guys do not

necessarily finish last, but they always finish

loved. Pride and envy are the primary sins

against charisma.

Conclusion

The six characteristics in AD&D gaming

have relevance to the real world, as much as

to role-playing games. The characteristics

can be improved, just as people can improve

themselves. The characteristics do not

define a person, any more than race, religion,

income, or shoe size do, although the

characteristics, like all other attributes, will

help to advance or to retard a person?s

enjoyment of life. Of all of these, the ones

that are least material ? charisma, wisdom,

and intelligence ? are the ones that are the

most difficult to improve, and the ones that

have the most effect on the quality of life.

Life is not fair. Some people are brilliant,

wise, and popular, while others of us. must

grind our teeth and wonder where we must

have been when the luck was being handed

out. A better closing line could not be found

than the immortal quote from the musical

Pippin: ?It?s smarter to be lucky than it?s

lucky to be smart.?

OUT ON A LIMB

‘Sixth sense’

Dear Editor:

Back in DRAGON #50 there was a letter <link>

suggesting that DMs exchange hints through

your magazine. Here’s my little addition:

Many times in fantasy books one reads

about the hero having a sixth sense. (“Jaxen

sensed something behind him. He whirled

about...”) Here is a flexible system for giving

adventurers a sixth sense. When the DM feels

that the character in question has a chance to

use his “adventurer’s sense,” he secretly rolls

to see if that character saves vs. breath weapon.

If the save is made, the character senses

something. Modifiers: Dwarves and gnomes

get -1 in woods, +1 underground; elves get -1

underground, +1 in woods; rangers and druids

get -1 underground, +1 outdoors; thieves get

+1 when alone; magic-users get +1 when magic

is nearby; clerics get +1 when the thing that

may be sensed is of an opposing alignment.

Chris Meyer

Marigot, Dominica, West Indies

(Dragon #63)