| - | - | "Dirty tricks" for Dragons | - | - |

| Dragon | Monsters | Dragons | Best of Dragon, Vol. III | Dragon 50 |

The dragon is nearly everyone’s favorite

monster. There is

something numinous in the name and the

image: sagacious,

fierce, terrible in ifs jaws and claws,

soaring aloft on great pinions, breathing great gouts of flame and smoke.

If such a creature existed in nature, even without fiery breath, its sire,

strength, mobility, and intelligence would

make it a formidable

foe of and competitor with mankind — our

advantage lying only

in numbers and a comparatively rapid rate

of reproduction.

But the dragon is an endangered species.

How can this be?

Just as the dragon is the favorite pet

of the Dungeon Master, if is

the favored prey of the adventurers. Is

the castle on the crag

haunted by a vampire? The characters shudder

and dare the

crag only with trepidation. Do the depths

of the caves hold

demons? Let’s wait until we’re a bit more

skilled... But let word

get out that a dragon lurks or fairs in

the vicinity, and every

character within earshot drops everything

else and begins sharpening sword with dragon in mind. Hirelings of every

stamp are

readily bought with the promise of sharing

in the dragon’s

enormous hoard. When the party has equipped

itself with control potions, all the magic that can be begged, borrowed,

or

stolen, and a train of pack mules to ferry

back the loot, it’s hi-ho

and off they go dragon hunting.

No other monster holds the potential of

such great gain at

such comparatively low risk.

Yes, I said low risk. What other monster

is liable to be found

sleeping obliviously in his den? What

other creature can be so

easily subdued and then sold on the open

market? And even

dead, the dragon alone is worth a sizable

ransom; its hide can be

sold for armor, its teeth for ornament,

its other parts for potions.

All other creatures with spell-using or

magic-like capabilities

have them pretty uniformly throughout

the type. A dragon with

no spell ability has only one other major

weapon: its breath,

which works only three times per day.

The claws of even the

largest gold dragon are no more formidable

than swords, and

many other creatures can approach the

damage of a dragon’s

bite, or possess abilities Iike paralyzation

or life draining that are

continually reusable.

The result is that few dragons are able

to stand up to the

invariably large and well equipped parties

that are thrown

against them. A carefully dispersed party

can avoid the blasts of

breath weapon with a fair chance of survival

by surrounding the

dragon and inflicting unnacceptable damage

on the beast’s

flanks and tail. Even if the dragon were

guaranteed of killing an

adventurer with each bite, a large party

would still overwhelm it

— especially if the dragon was awakened

from sleep by one or

more heavy-damage spells hitting home.

The dragon really ought to be more formidable

in melee, a

veritabte whirlwind of destruction, the

likes of which should

rightly frighten anyone in possession

of all his wits.

The damage done by dragon claws is far

too slight for anything except small representatives of the species.

An average-sized dragon ought to do twice

as much, and a huge dragon

perhaps three times as much. This would

reflect the enormous

strength these creatures possess. The

smallest dragon type, the

white, averages 24 feet in length. Even

if we assume that half of

the dragon’s length is made up of neck

and tail, the dragon

should still have as much mass as a large

elephant. Yet these

creatures have the muscular strength to

fly! Even if it is assumed

that the dragon’s power of flight is due

to an inborn magical

power, akin to the breath weapon, a creature

of that size must be

exceptionally strong to be able to move

with any speed. Therefore, a dragon ought to have at least the muscular

strength of a

comparably sized giant, if not more. Remember,

a giant cannot

fly by muscular strength alone, and if

giants had strength in

human terms in proportion to their size,

they would not even be

able to stand, and support their huge

frames.

Further, dragons have other assets that

are not considered in

combat. Unlike reptiles or saurians, dragons

are hexapedal, or

six-limbed, with the “extra” pair of limbs

being wings. Other

flying creatures, birds, bats, and the

extinct pterosaurs, have

wings made out of modified forelimbs.

Let us assume that, considering neck and

tail, a dragon might

have a winsgspread approximately equal

to its overall length. A

24-foot-long dragon would therefore have

a 12-foot wing on

either side. These wings are often thought

of as bat-like, a

membranous structure supported on a frame

of modified wing

and hand bones. (See the AD&D™ Monster

Manual illustrations

of the white,

silver,

and green dragons, and the dragonne.)

There is often a “thumb” claw at the “hand”

joint. The dragon

Smaug, as pictured in the television version

of The Hobbit, had a

weIl developed thumb and fingers at the

wing-hand, similar to

bats and flying dinosaurs. I personally

prefer this idea.

The point of this discourse on wings is

this: If you have ever

tried to corral a winged creature, a chicken,

or, worse yet, a large

goose, you know that it strikes out with

its wings. Roger Caras,

in his book Dangerous To Man, reports

several instances of fatal

injuries being inflicted by the blows

of a swan’s wings. Therefore, those characters standing to the sides of

the dragon must

dare the sweep of the dragon’s wings.

Those in front and near

the center of the wing would be in danger

of being struck by the

wing-claws. A wing buffet should do some

damage, mainly of a

bruising, battering type, tending to throw

adventurers away

from the dragon, and this should amount

to about one-third of

the dragon's normal claw damage. If the

target is within range of

the wing-claw, add an extra “to hit” roll

for the dragon, and if the

result is a hit, add the appropriate extra

damage, ranging from

1-2 points for a smash dragon to perhaps

1-10 for a big one.

An intelligent dragon might use its wings

in more than one

manner. A dragon with a gaseous breath

weapon could use the

sweep of its wings to fan the gas into

every corner of its lair. A

dragon that has started a fire with its

breath could fan the flames

into a roaring conflagration. A prudent

dragon might cover the

floor of its den with ice crystals, sand,

ash, or other loose material which could be whipped into a blinding, stinging

storm at

the onset of an attack.

On the subject of limbs, what about a dragon’s

hind feet?

Surely any dragon is intelligent enough

to kick out at something

attacking its flank, especially if the

front end is otherwise engaged. Allow one foot stamp by one of a dragon’s

hind feet in

every other set of attacks. (The dragon,

if not actually airborne,

has to stand on at least one foot at all

times, although it might be

supported by its wings to some degree.

This should do the same

damage as the foreclaws, but at -2 to

hit. If the dragon were for

some reason to engage in close combat

with some creature

nearly its own size, such as a giant,

then the dragon might well

employ both rear claws at once, in the

manner of some great

cats, especially jaguars and leopards.

In such attacks, the animal attempts to get the throat of its adversary

in its own jaws,

hooks its claws into the shoulders of

the opponent, and then (in

a dragon’s case with the aid of wings

for lift and balance) brings

the rear claws up to thrust into the midsection

of the victim and

rake downward to disembowel the enemy.

This is the only situation in which a dragon might reasonably be expected

to employ

both rear claws at the same time.

Finally, there is the tail. Many dinosaurs

and present-day

crocodiles and alligators use their powerful

tails as weapons. I

have assigned different types of tails,

reflecting the different

dragon types, in much the same way that

breath weapons might

be differentiated. White and silver dragons

I have given a relatively short, thick tail, with a ridge of horny plates,

that might

give the creature better traction in climbing

on ice. It would

strike against armor as would a mace.

To the traditional firebreathing dragons, the red and the gold, I assign

a traditional

dragon’s tail, long and tipped with a

spadelike blade. It would

strike against armor as does a sword.

Green and brass dragons

have a tail of medium length, tipped with

spikes similar to those

of a stegosaur. It strikes as a flail.

Black and copper dragons are

given a very long, whiplash-like tail.

It strikes as a dagger. To the

blue and bronze I have given a snakelike,

prehensile tail, which

does damage through constriction. It is

relatively long.

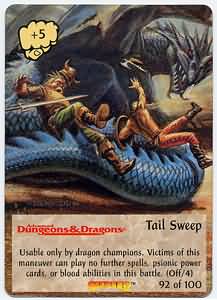

The dragon could lash with its tail once

per set of attacks,

striking either to the left or to the

right, but not to both sides at

once. A short tail, representing about

one-quarter of a dragon’s

overall length, might strike only through

an arc of 60 degrees; a

medium tail, about one-third of the dragon’s

length, through 90

degrees; a long tail, representing one-third

plus an additional

one-eighth of length, through an arc of

120 degrees, and a very

long tail, going up to one-third plus

an additional one-quarter of

the dragon’s average length, might strike

through an arc of 180

degrees, centering at the root of the

tail between the hind legs.

The difference is due to the fact that

the shorter tails are thicker

and less flexible.

Having given the dragon an assist in self-defense,

let’s look at

revised figures for a white dragon:

| Attack type and # | Small | Average | Huge |

| 2 claws | 1-4 | 2-8 | 3-12 |

| 1 bite* | 2-16 | 2-16 | 2-16 |

| 2 wing buffets | 1-2 | 1-3 | 2-4 |

| (2 wing claws) | 1-2 | 1-3 | 2-4 |

| Foot stamp (one every other time) | 1-4 | 2-8 | 3-12 |

| Tail lash | 1-8 | 2-16 | 3-24 |

Recommended damage by tail type

| Type of tail | Small | Average | Huge |

| Plated | 1-8 | 2-16 | 3-24 |

| Spiked | 2-12 | 4-24 | 6-36 |

| Spade | 1-10 | 2-20 | 3-30 |

| Whiplash | 1-8 | 2-16 | 3-24 |

| Constrictor | 2-12 | 4-24 | 6-36 |

These modifications and additions are suggested

to accurately reflect the fearsome fighters that dragons should be, without

unreasonable additions of powers or hit

dice. Instead, most of

what is proposed here can be logically

extrapolated from the

common assumptions about dragonkind. Recall

the famous

painting of St. George and the Dragon,

by, I believe, Titian. It

shows the pitifully small dragon fighting

off St. George with

both fore and hind claws, wings outspread,

and with the end of

its tail wrapped around the saint’s lance,

which is piercing the

creature’s chest. Further, these “extra”

tactics would likely be

used only when the dragon is trapped and

fighting in its lair. It

only makes sense that a creature able

to fly, in open terrain,

would prefer to attack from the air, thus

not exposing itself to

close assaults.

It is debatable whether or not dragons’

forepaws are prehensile — that is, are they sufficiently flexible and dextrous

to permit

the dragon to grasp things and handle

small objects with some

ease? If so, this opens up whole new possibilities.

Certainly, the

dragon culture has never been one of tool

users, but of robbers

and predators, preferring to take or steal

rather than forge or

build. However, that does not mean that

a dragon could not or

would not learn to use human-type implements

when they could

be beneficial. Monsters should make use

of the magic they

guard whenever this is feasible. A magic

ring might fit on a

giant’s finger, so why not on a dragon’s

claw? Is a spell-using

dragon enough of a magic-user to employ

a wand or stave?

Such answers are left up to the determination

of individual game

masters.

As a final word, I strongly urge that,

where one is dealing with

a more intelligent dragon, the 50% bite-or-breath

rule be

dropped. Instead, a canny dragon ought

to know when to husband the breath weapon, and when to expend it. Again,

I am a

believer in giving the monsters a fair

chance, based upon their

intelligence and ability. Dragons are

characters. too!

Slaying a dragon should be an accomplishment

that even

hardened adventurers would boast of and

would be proud to tell

their grandchildren about. So make it

tough, and a memorable

experience, not just another notch in

one’s sword.