| New Weapons | Equipment | - | Dragon #81 | Dragon magazine |

| A brief history | Chariots in the AD&D world | - | Construction and training | Weapons and warfare |

The development of chariots changed the

nature of combat during the early history of

mankind. The same thing will happen to an

AD&D campaign that incorporates

chariots.

Individual soldiers and warriors are

much more mobile, and more formidable,

when they sally forth into battle in a chariot

pulled by one or more powerful horses. But,

at the same time, charioteers can be vulnerable

to perils that footsoldiers don?t have to

worry about.

The Black Prince's

Chariot of Fear (Ral Partha)

A brief history

Archaeologists and historians have

uncovered evidence that chariots existed as

long ago as 2,000 years before the start of

the Iron Age. The wheeled vehicle was

probably invented in the Tigris-Euphrates

River area about 3500 B.C.; about 500

years later than that, two-wheeled vehicles

appeared in Mesopotamia. [Sumeria,

Babylon,

Assyria] Wheeled vehicles,

including the chariot, spread through

Asia and Europe and as far away as Sweden

and China during the next 17 centuries.

The Greeks were using chariots for

battles

and for racing before 800 B.C., most

notably in the Olympic games and at

Delphi. Greek racing chariots were light,

fragile constructions that were easily

smashed in collisions, often leaving the

drivers badly injured or killed. These chariots

were built light for speed, and to make

the inevitable crashes even more spectacular;

the races were a popular spectator sport

in those times. Celtic peoples introduced the

chariot to the British Isles in about 500

B.C., completing the spread of the chariot

throughout the civilized world.

The construction methods and materials

used in chariots varied greatly depending on

the use the vehicle was to be put to. Almost

all primitive chariots had wheels made of

two or three ?pie-slice? segments of wood

fastened together with transverse wooden

struts. The edges of these wheels were studded

with copper nails, or (especially after

2000 B.C.) fitted with bronze rims. The

wheels either turned independently on a

fixed axle or spun together on a rolling axle.

The domestication of the horse around

2000 B.C. had a profound effect on warfare;

now chariots could be pulled by animals

that had great mobility and maneuverability.

(Until that time, chariots had been

drawn by onagers, a breed of wild ass, or

some similar animal.) The invention of the

spoked wheel and the streamlined, semicircular

chassis, both of which probably

took place in India, further improved the

combat usefulness of chariots by making

them lighter (no more solid wheels) and

faster (less wind resistance).

At the same time, chariots became

heavier to better withstand the ravages of

battle. Earlier vehicles were so light as to be

flimsy, usually consisting of a floor of

wooden planks or woven leather strips

enclosed-by a wicker dashboard. As they

developed into military machines, chariots

began to carry bronze plaques on the front

and sides for protection from attackers. The

Celts carried heaviness to an extreme, using

metal (sometimes inlaid with enamel) for

the axle, the draft pole (the rod projecting

from the front of the chariot, to which the

horses were hitched), and the side boards,

and often also using metal in the construction

of the wheels.

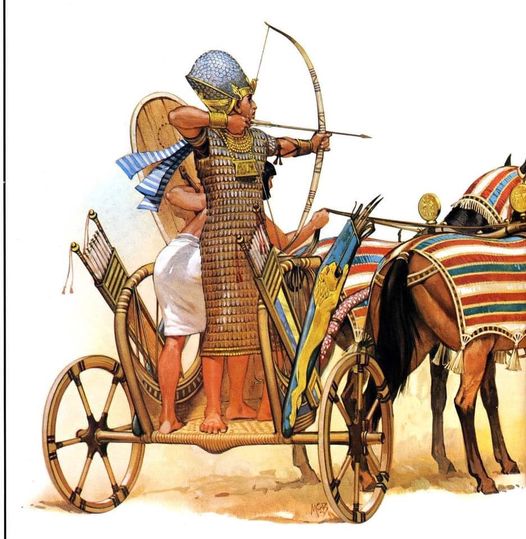

The military chariot was generally used

only by officers and the wealthy, because of

the expense of construction and maintenance

of such sophisticated vehicles; this

was particularly true of chariots drawn by

more than one horse. The earliest battle

chariot carried a spearman and a driver,

and was seldom actually used for fighting.

It was primarily a method of rapid transit

to, from, and across battlefields. It was

easier for an armed warrior to mount and

dismount from a chariot than from a horse,

and the presence of a driver meant that the

warrior-passenger didn?t have to worry

about steering or stopping, and was free to

concentrate on the more urgent matter of

engaging and defeating the enemy.

The art of charioteering was refined more

and more as time went on. It didn?t take

too long to discover that a warrior could

impart greater velocity to hurled weapons

(primarily spears and lances) if they were

tossed in the same direction the chariot was

going. Men on foot, of course, could be

trampled by horses or run over by the

wheels of a chariot. (This tactic was best

employed against unarmed men, because a

victim with a weapon stood a good chance

of being able to disable a horse when the

chariot got close enough.) British war chariots

had sword blades extending from their

axles, to cut the legs out from under the

Roman foot soldiers they were used against.

For AD&D game purposes and for simplicity,

chariots are of the most advanced

sort, and come in 3 types: 1-horse,

2-horse, and 4-horse chariots. Building

a chariot requires the services of a carpenter,

an armorer, a wagon builder, and a

horse trainer. Depending on the campaign

milieu, the carpenter and wagon-builder

roles may be combined in a chariot-builder

specialist, but the costs and time associated

with construction would not significantly

change. Used chariots and trained horses

may or may not be easy to find, again

depending on the campaign.

One-horse and two-horse chariots are

usually drawn by heavy warhorses. Fourhorse

chariots are usually drawn by draft

horses harnessed abreast of each other,

because of the teamwork required to pull

the vehicle and the general superiority in

endurance of draft horses over the long

haul. Four-horse chariots are more often

used as cargo carriers ? actually, they

resemble nothing so much as an ordinary

cart or wagon ? than as battle vehicles,

since they are much less maneuverable than

one-horse and two-horse chariots.

Below are three tables that contain statistics

on chariots in the AD&D game. The

carrying weights assume movement no

faster than the given movement rate; movement

is reduced in an inverse proportion to

the extra weight carried, down to one-half

normal movement when carrying a load of

twice the given weight. Beyond that point,

horses will be so severely slowed by the

weight that they will be unable to draw the

chariot at all for any length of time. When

charging, the horse(s) drawing a chariot can

move at 150% of the rate given; thus, a

one-horse chariot drawn by a heavy

warhorse could move at 15" when charging.

A chariot starting from a stationary position

can ?walk? through a turn with a

radius only slightly greater than the distance

from the horse's nose to the axle. A chariot

already in motion can turn through a maximum

arc as described in the third table

below. The sharpness of the turn (the

expanse of the arc the chariot can turn

through in one round) depends on the chariot

type, the amount of weight being pulled

(which affects the movement rate), and the

speed of the vehicle at the time the turning

maneuver is started. For example, a non-encumbered

four-horse driven chariot drawn by

heavy warhorses moving at full speed (15")

can turn through an arc of 90 degrees in

1 round, which menas it could make a

circle of 60" circumference in 4 founds'

time. This circle has a radius of about 9 1/2"

-- not a very sharp turn, at the scale of

1" = 10 yards. The same chariot can make a

sharper turn in less time by sacrificing

speed; at one-quarter of its full movement

rate, the vehicle can make a 180-degree

turn in one round and can turn in a circle of

7½? circumference in two rounds. This

circle has a radius of about 1.2?, or 12

yards.

Chariot movement rates

| Type | LWH | MWH | HWH | DH |

| 1-horse | 16" | 12" | 10" | 8" |

| 2-horse | 20" | 15" | 12" | 10" |

| 4-horse | 24" | 18" | 15" | 12" |

| Type | LWH | MWH | HWH | DH |

| 1-horse | 500# | 650# | 700# | 800# |

| 2-horse | 1050# | 1400# | 1500# | 1650# |

| 4-horse | 1600# | 2050# | 2400# | 2600# |

| Type | Chg. | Full | 3/4 | 1/2 | 1/4 |

| 1-horse | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 | 360 |

| 2-horse | 90 | 135 | 180 | 225 | 270 |

| 4-horse | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 |

The ?weight carryable? table assumes

non-magic armor equivalent to plate mail

on the front, back, and sides of the chariot.

The ?weight carryable? figures are in addition

to the weight of the vehicle itself, so

that a one-horse chariot drawn by a light

warhorse is able to carry a pair of 200-

pound men (driver and warrior), plus their

armor and gear, with a few pounds? worth

of carrying capacity left over. A chariot

adorned with lighter armor, or no armor at

all, would be able to carry more weight ?

up to the limit of the structural strength of

the chariot, of course. The carrying capacity

of a leather-armored chariot would

increase by 2000 gp per horse (4000 gp for a

two-horse vehicle, 8000 gp for a four-horse

vehicle), while a non-armored chariot made

of a material like wicker would afford an

extra 2200 gp weight per horse while enabling

the chariot to retain the movement

rates given in the first table.

Normally, chariot building will take about

one month. The cost of constructing the

chariot alone is 250 gp for a one-horse

vehicle, 500 gp for a two-horse vehicle, and

750 gp for a four-horse chariot. These costs

do not include horses, harnesses, barding,

and other accoutrements.

The construction time can be reduced by

one day for each 10% addition to the original

construction cost; however, no more

than one week can be taken off the construction

time in this manner without a loss

of quality and/or stability in the finished

chariot. For each day less than three weeks

that it takes to finish a chariot, there is a

5% chance (cumulative) that the chariot

will have a serious breakdown whenever it

is driven over rough terrain or into battle.

(The chance is 10% for a construction time

of three weeks minus two days, 15% for

three weeks minus three days, etc.) This

breakdown may be relatively minor, such

as the loss of a piece of armor plating; more

probably, it will be something major, like a

broken axle or draft pole, or the loss of a

wheel. Any of these last 3 mishaps

would almost certainly cause a wreck and

injure the driver and any passengers.

A chariot-builder who is skilled and honest

may provide characters with some good

advice on what kind of vehicle is best suited

for the terrain over which it will be driven.

A 1-horse chariot can cross any terrain

that a heavy warhorse can cross while carrying

a rider and equipment, except for soft

ground (chariot wheels would get bogged

down) or narrow passages (such as a trail

through a swamp). A 2-horse chariot

is

similarly limited, and can move at only 1/2

normal rate in mountainous areas,

heavy forest, and similar tough terrain. A

4-horse chariot may only be driven over

hilly, plain, scrub, and hard-packed desert

terrain (wind-blown sand dunes would not

allow passage), or on a well-kept road or

track.

A chariot can be built with carrying

places within easy reach of the driver and

passenger for various weapons, and may

also have special minor modifications such

as scroll-case compartments, hooks and

niches for oil flasks, and the like. A friendly

chariot-builder will include ?options? like

these at little or no extra cost if they are

requested before construction has begun.

Other more lavish or more unusual modifications,

such as hidden compartments and

gaudy decorations, can be built in but will

add at least 20% to the construction cost

and at least an extra two days to the building

time.

A character who has bought a chariot or

paid to have one constructed must spend at

least one week ?per horse? learning how to

drive the vehicle with proficiency (i.e., four

weeks for a four-horse chariot). Many variables

can affect the cost and time of this

training, such as the level and skill of the

teacher, the level of the pupil, alignment

differences between the two, racial adjustments,

and so forth. A figure of 50 gp per

week would serve as a base training cost, to

be adjusted as the DM sees fit.

Weapons and warfare

The spear and javelin have historically

been a charioteer?s favorite weapons.

Hurled weapons gain exceptional striking

power when used from chariots, translated

as a +2 bonus to damage if cast forward (in

the direction the chariot is moving) at a

target while the chariot is at full speed or

charging. Note, however, that the weapon

does not gain a bonus ?to hit? when used in

this manner ? and the DM may even

assign a penalty ?to hit? for a character

who has not practiced hurling a weapon

from a moving chariot, or for someone who

is attempting it in battle for the first time.

Other weapons may be employed from a

chariot, but it may be difficult to use them

effectively. Missile weapons (which can be

used only if the weapon-wielder is not the

driver) have a -2 penalty ?to hit? when

fired from a chariot moving at half to full

speed, and a -4 penalty ?to hit? when fired

from a charging vehicle. One-handed striking

and thrusting weapons may be swung at

nearby opponents at the normal ?to hit?

chance ? unless the wielder is also the

driver, in which case he must take a -4

penalty ?to hit? because he must keep the

reins held in his other hand. Two-handed

weapons like pole arms, battle axes, and

huge swords can only be used by someone

other than the driver. If the driver decides

to drop the reins and use any weapon to

attack, he suffers a -2 penalty ?to hit? in

addition to any other penalties that apply,

because he is no longer able to control the

direction and speed of the chariot.

A charioteer using a thrusting weapon

such as a lance, a held spear, or certain pole

arms gains a +2 bonus ?to hit? against

opponents in range of the thrust, and the

weapon will do double normal damage if it

hits while the chariot is charging. Note,

however, that these rules only apply if the

thrusting weapon is used in a thrust, not if

it is swung at an opponent. Also, there are

special problems involved. If an attack of

this type scores a hit, the weapon must save

vs. normal blow, or the shaft will break and

the weapon will be useless thereafter. (Treat

the shaft as ?thick wood? on the saving

throw table, unless it is made of a different

material.) The character using the thrusting

weapon must roll his ?open doors? chance

to avoid being hurled from the chariot by

the shock of the impact ? assuming that he

is holding onto the chariot or is otherwise

anchored inside it in the first place. A freestanding

driver or warrior who scores a hit

in this manner will always be thrown from

the chariot, whatever his strength. The use

of a thrusting weapon in this manner will

always allow the wielder the first attack

against a target on foot, regardless of initiative

rolls.

If he desires, the chariot driver may use a

medium or small shield while holding the

reins with his other hand; no penalties will

apply to the driver in terms of his ability to

drive or his capability to defend himself in

this manner.

In addition to their actual, physical combat

usefulness, chariots can serve as a psychological

weapon against certain opponents.

Any creature of less than 1 hit die

or smaller than size M that also has at least

low intelligence must make a morale check

or flee toward a place of safety when

?greeted? by a charging chariot, losing any

attack it would have otherwise been allowed

in that round.

The horse(s) pulling a moving chariot can

? and usually will ? trample any lowlying

creatures in its path. This group

includes, but is not limited to, snakes, small

animals, and men or humanoids who are

prone. Against creatures and characters

who are essentially helpless to prevent the

trampling, the DM should allow one automatic

hit (by kicking) appropriate to the

type of horse involved, plus an additional

1-3 kicks (only 1-2 for a one-horse chariot)

that are rolled as normal attacks. In addition,

the chariot gets one run-over attack

(rolled as if the driver had attacked the

victim) which will do 3-12 points of damage

if it hits. Because of the many variables

involved, the DM must moderate the out-

come of trampling attempts against men,

humanoids, or other creatures who are not

prone and helpless; unless deafened,

blinded, or otherwise incapacitated, a target

will usually be able to sidestep the onrushing

horse(s) as long as the target is capable

of movement. A target that doesn?t sidestep

quite far enough may be hit by short blades

attached to the outside of the chariot?s wheel

hubs. Each blade does 2-5 points of damage

if it hits, again making the attack as if the

driver of the chariot was rolling to hit.

Opponents who use good tactics do have

a chance against a chariot. Monsters of

average intelligence or higher, especially

humanoids and other creatures who can use

missile weapons, will often attack a chariot?s

horse(s) in preference to the driver, in the

hope of upsetting the chariot. If any of the

horse(s) pulling a chariot sustains damage

equal to one-third or more of its original hit

points, the animal will panic, and other

horses, even if uninjured, may follow suit.

The driver has a 10% chance per level of

experience to be able to bring the horse(s)

back under his control, and if that doesn?t

happen, the chariot will crash. A chariot

crash will do 1-8 points of damage per 6? of

speed (round down) to the driver and any

passengers. If a horse is seriously wounded

(more than 50% hit-point loss) or killed and

the driver does manage to maintain control

of the vehicle, the best he will be able to do

is bring the chariot to a stop, and it cannot

be driven any further until a fresh horse is

hitched up.

The accompanying diagram shows topdown

views of what each type of chariot

might look like, with shaded areas indicating

the effective ranges of various attacks

that can be effected by the occupants and

the horses. As in all situations involving

rapid movement, the DM must keep careful

track of the locations of all characters, animals,

and vehicles involved in a confrontation

to determine if and when combatants

are within striking distance of one another.

<ADD DIAGRAM HERE>