SWORDS

SLICING INTO A SHARP TOPIC

BY DAVID NALLE

| Edged Evolution | - | Forging the Sword | - | The Sword in the Fantasy Campaign |

| Equipment | 1e AD&D | - | Dragon #58 | Dragon |

For many, fantasy conjures up the image

of a brawny barbarian

brandishing a

burnished blade. Alliterations aside, the

sword was usually the weapon of choice

for hand-to-hand combat, be it a switchblade

or a great sword.

And, regardless of changes in design

and use, the parts of the sword remained

basically the same from the beginning of

the Middle Ages to the present.

The blade was the essential component

of a sword. Sometimes references

to a sword include only its blade, the

irreplaceable and lasting part of the

weapon. The other parts are termed accoutrements,

which could be removed,

changed or replaced.

A medieval blade usually had two cutting

edges; ranged between 30 and 70

inches in length; was pointed; and often

incorporated design features such as a

blood runnel. The blade bottom ended in

the tang, a metal spur used to attach the

blade to the rest of the weapon. The tang

was thinner than the blade, usually four

to 12 inches long and an inch or so wide.

On early swords the tang was welded to

the blade, but these types tended to

break off; later, the tang was forged as

an

integral part of the blade. The tang was

designed so that a tang nut could be

hammered, shrunk, or screwed onto the

end to attach the pommel and hold it

onto the hilt.

The guard was a forged iron crosspiece

attached perpendicular at the

junction of the blade and the tang. It

varied

in size and shape, and the final form

in the Middle Ages was from five to 14

inches in length. It served to keep the

weapon of an opponent from sliding up

the blade and cutting the wielder’s hand.

During the Renaissance guards became

much more complex, protecting the hand

from lighter, pointed swords.

The hilt was a covering over the length

of the tang from the guard to the pommel.

It was usually made from cloth or

leather, textured with string or wire for

a

better grip.

The pommel changed with fashion

and can be used to date swords. It was

designed to keep the sword from sliding

from the the wielder’s hand and also balanced

lighter swords. It was attached to

the tang and sometimes served as a tang

nut. The pommel usually was heavy metal,

sometimes covered with cloth. At

first it was just a ring or crossbar, though

later pommels were often sculpted, or in

geometrical shapes. This most visible

part of the sword was ornamented in any

of a number of ways. Heavy pommels

also could be used as clubs.

The parts of the medieval sword, as

illustrated on a typical long

sword.

Note that the top drawing includes the

blade and tang only; the bottom drawing

shows the accoutrements generally

found on swords during the Middle

Ages.

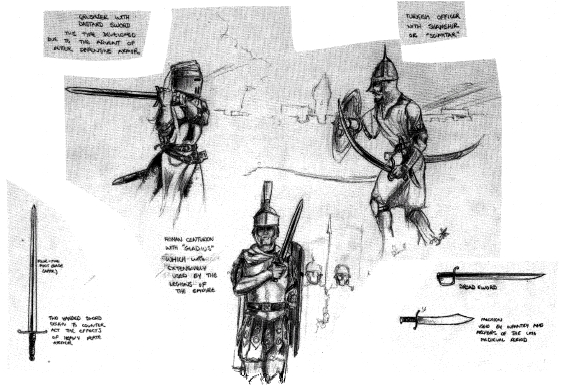

Four different types of swords used by

northern European warriors: The long

sword as used by the Vikings (top left),

the German spatha (top right), the

broadsword, an offspring of the spatha

(bottom left), and the pointless Celtic

sword (bottom right).

Swords changed history and were

changed by history. The bastard sword

(top left) and two-handed sword

(bottom left) were responses to

improved armor, while the falchion

was

more practical for archery units than

the broadsword (bottom right).

Damascene-type swords, such as the

scimitar (top right), were prized

possessions, while Rome’s legions

spread the gladius (bottom center).

EDGED EVOLUTION

The sword, which slowly evolved from

the Greek spear,

first came into popular

use during the Roman Empire. Three

early types of swords developed: the

Celtic sword, the Roman gladius, and

the German spatha. Though different in

design, aspects of each were eventually

incorporated in the weapons associated

with the age of chivalry.

From about 400 BC to AD 100 the Celtic

sword was popular with Celtic and

Teutonic tribes spread from Scotland to

Turkey. (Their main concentrations were

in the British Isles, the Balkans, and

France.) The broad, flat-edged Celtic

blade had no real point, and was used

exclusively for cutting or hacking, making

it similar in function, if not appearance,

to the battle axe.

The blade was about 30 inches long

and two inches wide. The point was

rounded to a width of about 1½ inches.

There was no blood runnel, and the

guard and pommel were usually either

an iron bar or a bronze ring, usually not

very large. The function of this sword

was very similar to that of the battle

axe.

The spatha was a longer sword used

mainly by the Gauls and Germans. A

spatha was usually about 50 inches long

with a three-inch-wide blade. It was a

cutting weapon with two edges. Some

had points, though these were usually

not used.

The Germans spread this ancestor of

the broadsword around Europe while

serving as mercenaries for Rome. The

blade was generally four-sided, with a

diamond-shaped cross section. The pommel

and guard were usually bars of metal,

or metal-bonded wood or bone.

The gladius was one of the finest fighting

weapons of the period, mass produced

and spread by Roman legionnaires.

The typical gladius was somewhat

less than 30 inches in length, with

the greatest blade width about 1½

inches.

The blade was four- or eight-sided, very

stiff, and had a sharp point.

The Roman shortsword shown in the

movies is much more similar to the Celtic

sword than to a historical gladius. It

was

a stabbing weapon for use against lightly

armored troops. The guard was usually a

small bar, and the pommel was of variable

shape, though it was usually a heavy

bar or block. The cross-section of the

blade was either a triangle or a squashed

octagon.

European tribes used these three early

swords until the 9th century, when Ulfberht,

a Teuton bladesmith, developed

the broadsword, the dominant blade of

the high Middle Ages. This was a longer,

better-balanced version of the Celtic

sword and incorporated the length of the

spatha and the point of the gladius.

Ulfberht’s sword was originally intended

for use against chainmail and had a

point for thrusting and an edge for cutting.

As plate armor came into greater

use in the 13th century, Ulfberht’s design

was expanded to form the three basic

sword types of the high Middle Ages: the

broadsword, the bastard sword, and the

two-handed greatsword. Length and

weight were increased in these swords

to increase cutting ability.

The broadsword followed the original

design. It was about 50 inches long and

weighed around two pounds, and was

single- or double-edged. The bastard

sword was similar, but was intended to

be

used with either one or two hands to

allow a heavy double-handed blow. Bastard

swords were about 60 inches long

and weighed some four pounds. The hilt

was lengthened to leave room for two

hands. The greatsword had a very long

hilt to accommodate two hands with

ease, as it was always used with two

hands. It tended to be 70 inches long and

weighed up to seven pounds. These

swords usually had triangular blades

and points, though these were omitted

on some longer blades that were impractical

to thrust with.

(A bit of clarification to reconcile

gaming

nomenclature with historical usage:

The double-edged broadsword described

above translates into the longsword

of

AD&D

and D&D rules; the gaming

broadsword

has a single-edged, triangular

blade. The Celtic sword and gladius

both

correspond to the short sword as described

in the rules. The bastard sword

does damage as its gaming counterpart,

but only when swung with two hands.

When used one-handed, the bastard

sword does damage as a long sword.

Lastly, the spatha should be considered

a long sword for gaming purposes.)

Changes in armor design and the style

of combat prompted changes in sword

construction and the sword adapted to

stay the most versatile and practical

weapon for the medieval warrior. If gunpowder

had not changed warfare so radically,

heavy swords and armor might

have stayed to this day. But, when the

gun made armor obsolete, the sword

changed again to the light, pointed form

of the post-medieval period.

After the Roman Empire, most swords

were made in Scandinavia or Germany.

The most noted swordsmiths of this period

were Ulfberht, Ingelrud, Romaric,

Ranvik, and Eckelhardus. It was not until

the later Middle Ages that towns in

southern Europe and the Middle East

became famous for their swords. Eventually,

the Syrian city of Damascus became

legendary for the quality of the

steel in its swords. Toledo did not achieve

renown until the 15th and 16th centuries

when higher heats allowed duplication

of Damascus’ quality.

Most swords were not made at famous

forges by smiths remembered by history.

Every smith had his mark, and swords

bearing hundreds of different marks survive.

Every town had a swordsmith and

some, like London, were large enough to

have a guild of bladesmiths and one of

hiltyers as well. Wherever knights and

men at arms needed weapons, smiths

would be. The craft of sword forging was

widely known throughout Europe, although

some smiths had more skill than

others. The process was unreliable,

enough so that any smith might make a

great blade, though some might never

do so.

FORGING THE SWORD

In the Middle Ages swords were made

from various grades and types of iron

and steel by a number of different methods.

Ore — and the way it was refined

— and the skill of the

smith determined

the quality of the sword.

The fall of the Roman Empire also

brought the end of its European mines.

Early medieval smiths found ore where

they could, mostly in bogs or other areas

needing little or no excavation.

Ore found in bogs contained many

impurities that made for poor iron unless

removed. Smelting under high heat

burned some foreign matter; the smith

removed the rest by working with the hot

iron.

During smelting, ore was sealed in a

clay furnace that was broken up afterward.

The metal was heated to around

500 degrees Centigrade, much cooler

than the 1,100 degrees used today. After

smelting, the remaining slag was worked

out by the smith to produce wrought

iron. If too many impurities remained,

the iron was resmelted.

The smelting and working methods

were not completely effective, and much

of the iron of the Dark Ages and the early

Middle Ages was so poor as to be worthless

in combat.

The goal in forging a sword is stiffness

and a good edge. The dangers are making

the blade too stiff, softness, or brittleness.

Western European swords tended

towards softness, while Eastern

swords were often brittle.

Swords made from plain wrought iron

were much too soft, so steel was made

by treating the hot iron with charcoal.

This carbon hardening process required

great care, because too much carbon

could make the the sword brittle. The

ideal carbon content was about .7%.

Hardness and flexibility were enhanced

by tempering, the process of alternately

heating and cooling the blade. This

draws the carbon to the surface of the

blade and spreads the carbon by expanding

and contracting the metal. Many

substances were tried for cooling the

steel. One quality smiths looked for was

a high boiling point, so the coolant

would not boil away when it touched the

hot metal. Some of the most popular

coolants were water, oil, urine from goats,

molten lead, honey, radish juice, moist

clay, or, in the east, human blood. The

most effective of these were probably

urine, oil, and radish juice.

The carbon content of the blade was

often proven during the tempering process.

Blades with too much carbon could

shatter when cooled. Most smiths lost

several swords due to this reason for

each one they completed.

The two main methods for forging

quality swords in the Middle Ages used

different approaches to the problem of

generating relatively uniform hardness

and flexibility in the blade. In the east,

a

technique called Damascene was dominant,

while a simpler method called pattern

welding was popular in the west. A

third system called clay casing was also

used to forge lower-quality swords.

Each of these methods leaves a distinct

pattern in the blade from the deposit

of carbon in the tempering process.

This pattern is especially clear after

a

number of years when the carbon is

highlighted by the rusting of the metal.

Both Damascene and pattern welding

were complex techniques and difficult to

perfect. Damascene produced a somewhat

better blade, but more failed blades

were produced in the process; pattern

welding was quicker and more reliable.

Clay casing was used mostly for producing

mass-market, single-edge blades

such as the falchion. It was faster than

other methods, but the product was far

inferior.

None of the techniques was really

quick. A smith needed from 40 to 70

hours to make a good sword, and one

commissioned by a special client might

take weeks. In the Middle Ages, it was

impossible to make a truly fine blade

quickly.

Clay casing was a simple process. A

blade was beaten from a piece of hot

steel. The back of the blade was then

coated in clay with the edge left bare.

After the clay was applied the blade was

fired again and cooled. The result would

be the tempering of the edge of the blade

while the clay-covered back remained

flexible. This gave a good edge and retained

some flexibility. The relatively

simple process took only a few hours for

each blade. The product was rather unreliable

and poor against armor. Clay

casing left a distinct line of discolora-

tion down the length of the blade, marking

the high-carbon area from the softer

metal.

Damascene resulted in a very high

carbon content, and a hard, sharp blade.

This was achieved through repeated

tempering and working the red-hot metal.

A Damascene blade was tempered

twice as many times as other blades,

sometimes with different coolants. Tempering

might be done as many as 25 times,

with carbon content usually between

.7% and 1.5%. To reach this high level

carbon dust was added to the hot metal,

melted and mixed in withThe smith divided

the hot iron into four

long, thin bars, which were put in boxes

of carbon dust. The metal absorbed the

dust, becoming hard on the outside, but

keeping a soft core. This resulted in high

external carbon content, but an overall

content of only .2% to 1%. Next, the four

bars were heated and twisted together to

the metal.

The smith worked the red-hot blade to

disperse the carbon into small pockets

all through the blade. The metal was

beaten into thin strips of different carbon

levels that were melded together in layers,

with the most carbon on the outside.

The final working of the complete blade

fixed the carbon in place as much as

possible. The ideal pattern of carbon

pockets was in 40 rows running up the

blade forming the “Mohammed’s ladder.”

Swords with a perfect ladder fetched

remarkable prices.

In the final step the Damascene blade

was etched and polished with a mineral

called “Zag,” then fitted with hilt, guard

and pommel. Lesser blades were shipped

from Damascus to be accoutered and

sold by local smiths.

Pattern welding was the preferred technique

of western European smiths. This

was a fast and effective method of forging,

but in many ways was uneconomical,

wasting more than half of the steel in

the sharpening process.

The smith divided the hot iron into four

long, thin bars, which were put in boxes

of carbon dust. The metal absorbed the

dust, becoming hard on the outside, but

keeping a soft core. This resulted in high

external carbon content, but an overall

content of only .2% to 1%. Next, the four

bars were heated and twisted together to

produce a long cable that cooled into a

single piece and was hammered flat after

it cooled. This cable-like affair was then

filed down to about 40% of original size

and an edge put on. The twisting left a

candy-stripe pattern of carbon lines in

a

criss-cross design.

The final step was to treat the blade

with acids, usually urine, acetic acid,

or

tannic acid, to give a good finish. Tannic

acid was the best finishing acid as it

helped prevent rust. After this the accoutrements

were fitted, and the blade was

ready for sale.

THE SWORD IN THE

FANTASY CAMPAIGN

When a player asks for a special sword

to be forged, the DM needs an idea of the

long and rigorous process involved in

making a fine weapon. Swords weren’t

just stamped out by the hundreds. Each

one was a unique work, embodying the

skill of a bladesmith. Swords of quality

should not be sold cheaply and are a

warrior’s mark of success. Granting a

first-class sword to a vassal is a sign

of

great favor. because of the symbolic

purpose of the weapon and its great expense.

A lord had such a blade made as a

reward to his bravest general or knight.

The fine sword is a weapon of kings

and conquerors. The right to bear one

should be reserved only for the finest

of a

race and should be a mark of valor.

The sword is not just a weapon, but

represents the product of a complex and

exacting art. No mere lump of iron, it

can

give life — or take it away.