|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There’s no putting it off any longer.

You’ve been a DM for years,

and the campaign world you created and cobbled together has outlived its

usefulness.

Your players’ characters

have explored practically every nook and cranny,

and you’ve become intimately

familiar even with the parts they haven’t been to.

Your pride in the world

has waned because it doesn’t bring out the same sense of wonder and mystery

in you that it once did --

and if the wonder and mystery

is diminished for you,

then what must things be

like for your players?

Or . . . you’ve decided to

take the plunge and become a DM for the first time.

You’re pretty familiar with

the rules of the game, and you’ve learned

a lot from the campaigns

you’ve participated in as

a player. But those weren’t your campaigns,

and all the ideas that have

been building up in your conscious

and subconscious mind are

aching for release.

No matter which of those

situations you’re in, you stand at a

crossroads -- a focal point

from which radiate a virtually infinite

number of paths. You are

about to start making a new campaign

world, and it all begins

with the first line you draw on a blank piece

of paper that will become

the world map. With every mark you

make on that paper, you

eliminate some possibilities and open up

others. At some point, when

the paper actually begins to look like

a map, there will be no

going back (without starting all over

again). By then you should

be confident that what you have done

will stand as a firm foundation

-- a structure to which you can

(and must) add detail,

but a structure that can support detail without

limiting your creativity.

This section of the WSG

will not tell you

how to make a world where

water flows uphill, a desert is bordered

by a swamp, and a steaming

tropical jungle is nestled between

two arctic mountain ranges

several thousand feet above

sea level. If your ideas

run along these lines, you don’t need any

help -- just put pencil

to paper, let your imagination run free, and

see what you end up with.

The AD&D@ game can be played in any kind

of universe, even

one where the natural laws

of our Earth do not necessarily apply.

* But for the purpose of

this discussion, we’re going to use the

same assumption that underlies

practically every other paragraph

in this book: The campaign

world is one that could exist on

Earth, or at least under

Earthlike conditions. Water flows downhill;

you can’t go from a swamp

to a desert without passing

through (or over) some other

kind of land; terrain features that are

found at sea level in the

tropics are not also found thousands of

feet above sea level surrounded

by snow-covered peaks.

An Earthlike campaign world

has some advantages over a

“freeform” environment or

one that is deliberately created with

unearthly features. First,

both you and your players are naturally

familiar with the features

of the planet we live on; when you say

“mountain,” they know what

you mean. But if you create a world

where “mountains” are made

of wood (for instance), your players

are going to ask questions

and you’re going to have some explaining

to do: Are these wooden

mountains slippery? Do they

burn? Can the characters

get splinters if they’re not careful? For

every “unrealistic” question

that players come up with and you

are forced to address, the

players’ suspension of disbelief is

strained a little further.

When it gets strained too far, players become

preoccupied with the fact

that, after all, they’re “only” playing

a game -- and role-playing

falls by the wayside in favor of an

artificial “contest” between

the players and the world they’re trying

to understand.

** Second, homo

sapiens is the dominant and predominant creature <>

in the game universe that

is described in the rules, and the

campaign world should be

one in which PCs (either

human or demi-human) can

survive and prosper -- one in which

they can feel at home without

having to undergo some biological

or artificial adaptation.

For instance, if you think it would be fun

for your world to have an

atmosphere of methane instead of air

that is normally breathable

by characters, think again. Even if

every character was somehow

equipped with an apparatus that

allowed him to survive,

no character in his right mind would set

out on an adventure for

fear of breaking or losing his life-support

apparatus. And if the apparatus

can’t be broken or lost, or if the

characters all have “special

lungs,” then why bother to create a

poisonous atmosphere in

the first place?

*** Third (and related to

advantage number one), the best kind of

campaign world is one that

is everpresent but usually inobtrusive.

The world should be a backdrop

for the activity that takes

place between the characters

and creatures that live in it -- the

location of a conflict,

but not the source of the conflict itself. The

way to keep the world in

its proper place is to make it “ordinary,”

so that PCs can concentrate

on what they’re doing

instead of where they’re

doing it.

All of the foregoing is not

meant to say that some deviation from

the norm is not a good idea.

In a campaign world of continental

proportions, there’s plenty

of room for your pet ideas -- but USE

them on a small scale. Replace

that clear, tranquil river with water

that is always at the boiling

temperature, so that even characters

who can swim

won’t be able to just jump in and paddle along

-- but don’t make every

river a scalding experience. Create a forest

of trees that not only lose

their leaves in the autumn, but actually

pull themselves down into

the ground when the first frost hits.

When a fantastic feature

of this sort is localized, it remains intriguing;

when it’s used everywhere

throughout the world, it loses

its distinctiveness and

becomes an obstacle instead of an oddity.

If you’ve ever spent ten minutes

looking for a pair of sunglasses

and then had someone else

tell you they’re perched on

top of your head, you’re

aware of two basic facts about the human

mental process and our powers

of observation: The obvious

is often overlooked, and

what’s obvious to one person may not be

apparent to another. Even

if you know how to create a world map,

read through these step-by-step

suggestions in case you run

across something that hasn’t

occurred to you before.

1. Settle

on a scale. Decide how much area you want your world

map to cover. It isn’t necessary

to create an entire planet at one

time; stick to something

the size of a continent or part of a continent.

The DMG, on page

47, recommends that

the scale of a world map

should be from 20 to 40 miles per hexagon.

At 40 miles per hex (measured

across the middle),

a standard

8 1/2 x 11-inch piece of small-hexagon

mapping paper covers

an area of roughly two million

square miles - 1600 miles in the

long dimension and 1250

miles in the short dimension. If this isn’t

a large enough area for

what you want to create, simply fasten together

two or more sheets of hex

paper and work in an even

larger scale (50 or 60 miles

to the hex) if you want to. Everything

will be scaled down later

when you need to detail a certain section

of the world; for now, all

we’re concerned with is describing

the size and shape of the

world and locating its most prominent

physical features.

The outline of your world,

and any other features you draw on

the map, need not follow

the boundaries between hexagons; in

fact, it’s much better if

you don’t restrict yourself in this fashion.

The hexes are there only

for the purpose of regulating size and

distance. As you fill in

the features on your map, try to pretend the

hexes aren’t even there

-- or, better yet, draw the map out in

rough form on blank paper

and transfer it to hex paper later.

Sheets of hex paper, with

hexagons of a different size on each

one, are provided in the

back of this book (pages 124, 125,

126).

The <>

owner of the book is hereby

granted permission to make photocopies

of the sheets for his personal

use only.

2. Start

at the bottom. Decide whether your creation is going to

be the size of a continent

or just part of one, and then pencil in an

outline that describes the

coastline. Now’s the time to plan for

major islands, long peninsulas,

and other ultra-large-scale geographic

features. If you’re creating

an entire continent, you must

know whether the continent

is an island in itself or if it connects

above water with another

large land mass. Unless you have a

reason for creating a continent

surrounded by water, extend the

land mass off the edge of

your map paper in at least one direction.

This keeps your options

open: If you want to connect another

land mass to this one later,

you can do it without redrawing

anything you’ve already

done. If you want to turn the continent

into an island, all you

have to do is make a small extension of your

original map containing

the previously uncharted seacoast.

At this point, your map

shows all the places where the land

meets the sea, at least

as far as the major land masses are concerned.

By definition, these lines

also show the location of zero

elevation, or sea level.

3.

Now

take it to the top. Decide where to place the mountain

ranges,

and

determine how high the tallest peaks will rise. Don’t

make

them too frequent or too high; characters shouldn’t have to

scale

something the size of Mount Everest once every few days

during

a cross-country trek. But don’t make them too low, or they

won’t

provide a good challenge and change of pace. Locate the

tallest

peaks individually and decide

how

high they stand. If any

peaks

are higher than 10,000 feet, draw shapes around those

points

indicating the line of 10,000-foot elevation. Then do the

same

for a line of 5,000-foot elevation.

Now

your map is a rough topographical map, showing the highest

points

of elevation on the continent and the area’s lines of elevation

at

5,000-foot increments. The rough shape of the world, in

all

three dimensions, has been determined.

4. Place

if on the planet. Decide where your world is located

with respect to the poles

and the equator of the planet it is a part

of, and then note some rough

boundaries where climatic zones

change. The world you start

with need not run the gamut from

arctic

to tropical climate; on the other hand, it

doesn’t need to be

the size of the Earth’s

northern or southern hemisphere in order

to contain all five climatic

regions. At this time, you should also

determine the direction

of the prevailing winds in each climatic

area of the world; see the

weather-generation system in the appendix

for general rules to aid

you in these decisions.

5.

Just

add water. Now that you’ve placed the areas of high and

low

elevation and you know what the climate is in any spot on the

map,

you can draw in rivers and lakes. Rivers begin at high elevation

and

run toward the ocean (or some other place at or near

zero

elevation). A large river usually has several tributaries that

flow

into it, and extremely large river systems (such as the Mississippi

or

the Amazon, and all the tributaries that feed them) are

rarely

found more than once or twice in a continent-sized area.

Large

inland bodies of water (wide-ranging river systems and

huge

lakes) are somewhat less frequent in subarctic

climates

than

in warmer areas, but a subarctic region may be laced with a

dense

and intricate network of smaller rivers and lakes; look at a

map

of Canada for an example of such a network (as well as

some

areas, such as Great

Bear Lake and Great

Slave Lake, that

contradict

the above statement about frequency of large bodies

of

water). Don’t be bashful about laying in rivers and lakes, but

don’t

run a stream through every hex unless you’re designing a

world

with no deserts.

This

is also the time to decide where you want your swamps.

Put

them in areas of low elevation, usually near or on the seacoast

and

usually in an area that has a lot of rivers or lakes.

6.

What’s

for desert? Now that you know where water

is and

isn’t

located, you can plan your desert areas. Have an eraser

handy

for this stage (if you haven’t used one already), because

you

may want to dry up a few rivers and lakes along the way.

On

Earth, most deserts are located in subtropical

climate and

the

part of the temperate zone closer to the

subtropical area (the

southern

half of the zone in the northern hemisphere, the northern

half

in the southern hemisphere). This is because of global

wind

patterns; the prevailing winds blow generally

east to west

around

the equator, and usually in the opposite direction in the

temperate

regions. When they meet each other in the upper atmosphere

over

the AREA in between, the cool upper air

descends.

As

the air gets

lower, it gets warmer, and its ability to retain moisture

increases;

thus, the water vapor in the air remains suspended

and

is not released as precipitation.

Farther

away from the tropics, deserts are often located

on the

downwind

side of high mountain ranges. When the wind hits the

slope

of a mountain, the air rises and becomes cooler. Since cool

air

cannot retain moisture as easily as warm air, the water in the

air

is released as precipitation on the

slope

facing the wind direction,

and

by the time the air crosses over the mountains all or

most

of its moisture has been depleted.

With

these two facts in mind, place your deserts, and be prepared

to

obliterate a river (or at least change its course) if your

map

shows water flowing through an area that would make a

good

desert.

7.

May

the forest be with you. You’ve already established

lots of

places

(high mountains,

deserts,

arctic

regions) where forests

can’t

grow; now is the time to decide where they do appear. Mark

off

the forest areas on your world, remembering that they are

more

likely to be located along or near large

bodies of water.

Don’t

go above the tree line (where arctic climate

begins) and

don’t

put a forest right next to a desert, unless you have a

specific

reason

for creating a region of “unearthly” terrain

in that AREA.

8. None

of the above. Any terrain that you haven’t designated

as seacoast,

mountains,

swamp,

desert,

or forest must be either

hills

or plains. If it has no other distinguishing characteristics,

the

area adjacent to a mountainous

region should be considered as

hills. You may also want

to spot some hilly regions in the middle

of an AREA that is flat

and featureless, just for a little variety. After

that, as the next-to-last

step in this process of creation and elimination,

anything else is plains.

9. Large-scale

details. Up to now, we’ve been dealing in features

of immense scale -- the

aspects of a world that would be

apparent to someone from

a vantage point several dozen miles

above the surface. Now it’s

time to narrow the scope just a bit and

toss in a few details. Does

that huge desert have an oasis,

or

more than one? Is there

a pass that runs through that awesome

mountain range?

Mark these features now, and you won’t have to

worry about putting them

in when characters decide to look for

them. This is also the time

to make any large-scale additions or

alterations to the terrain

features. If you want to run a thin strip of

forest

land on either side of the big river that

slices through a vast

plain,

do it now. If you want to send a river

coursing through a

desert,

that’s okay, but be sure to border the river

with a couple of

strips of something other

than desert. Make any large-scale finishing

touches to the terrain that

you think are appropriate, until

you’re satisfied with the

lay of the land.

10. Points

of interest. While you’re still looking at things from an

ultra-large-scale viewpoint,

you should pinpoint the locations of

special isolated features.

If your world has features resembling

the Grand Canyon, Death

Valley, or the Yellowstone area, locate

them now. This is also the

time to determine if your world has

earthquakes or volcanoes

and, if so, where you ought to place

the fault lines and the

hot spots.

An earthquake can occur almost

anywhere, but the most frequent

and most severe quakes take

place along major fault lines.

These lines are often located

where the land rises abruptly in elevation,

and especially near the

seacoast. (The San Andreas Fault

in California is an example

of this.) A major fault line can also occur

in the middle of a mountain

range, running along the long axis

of the chain of mountains.

If your world has features that might be

the location of major fault

lines, sketch in those lines now.

Individual volcanoes

do not need to be placed on a map of very

large scale; this would

be as difficult as locating every individual

mountain peak. However,

you should know where the “hot

spots” are, because these

are the areas where volcanoes will be

found. Each hot spot is

an AREA of 20 to 40 miles in diameter, usually

located in the lower regions

of a mountain range or along a

major fault line that cuts

through a mountain range, representing

a place where magma lies

close to the surface.

Not every major fault line

produces frequent earthquakes, and

not every hot

spot contains active volcanoes within

its AREA, so

don’t be stingy about locating

these special features. If you don’t

want to make all of them

active right away, no one else (in other

words, the characters) will

have any way of knowing that they exist.

But if you decide that a

long-dormant volcano is suddenly going

to spring into life, you

can cause the eruption by design rather

than on a whim. The more

decisions you make in the creation

stage, the fewer times you’ll

find yourself caught short later.

You now have a one-of-a-kind

creation -- a map that looks like

no other map ever made.

But it’s still not ready to use as the location

for adventures until you

bring it alive. Divide the terrain into

countries, sketch out political

boundaries, and decide where the

major population centers

are located. This is a much more complex

and difficult process than

that single sentence would indicate.

Unless you have reasons

for doing things differently, use

these general guidelines

to rough out the political and cultural

makeup of your world.

1. The largest population

centers are usually located adjacent

to large bodies

of water, especially along the seacoast or on the

shores of bodies of water

with an outlet to the sea. The health of a

city depends on commerce,

and the most efficient way to move

trade goods from one place

to another is by boat or ship.

2. Other large cities

may be located in areas with an abundance

of a useful natural resource.

A city can spring up in the

foothills of a mountain

range several days’ travel from the nearest

large river, as long as

a road exists (or can be built) from that city

to another city that lies

on the river. The first city is a place where

miners can bring their take

to be assayed and refined, after which

it is sold to a merchant

caravan operation that transports it to the

manufacturing and shipping

center that lies on the river.

3. Areas that are physically

isolated tend to be politically independent,

at least at the beginning

of a world’s political history (before

an aggressive neighbor decides

to try expanding its

boundaries). An AREA that

is ringed by high mountains, or composed

entirely of mountains, will

have a different government

than the areas around it.

(Switzerland is a good modern-day example.)

The areas on either side

of a vast desert will usually not

belong to the same country,

since it is very difficult for a single

central government to successfully

exercise its power across a

large expanse of impassable

terrain.

4. In the absence of other

factors, rivers often serve as political

boundaries. This is to your

advantage and the advantage of the

people who live in the adjacent

countries, since there can be no

doubt about where one country

ends and another one begins.

5. Enclaves of humanoids

and demi-humans will usually occur

in terrain

that is suited to them, according to the descriptions of

those creatures given elsewhere

in the rules. Elves tend to be

more numerous in forests,

dwarves in mountains, and so forth.

Flesh out your world, still

working in large scale, by spotting at

least the larger cities

and the places where a certain type of creature

forms the predominant part

of the resident population. Outline

the countries, perhaps leaving

some of the political

boundaries indefinite (that’s

how wars get started). Then use a

combination of common sense

and imagination to make some

general assumptions about

the state of the world, such as:

Country

A doesn’t like Country B because B insists on sending

all of

its refined iron ore eastward into Country C. It doesn’t seem

to matter

that A and B are separated by a mountain range

that

makes

overland traffic between the countries almost impossible.

Country

B, being no dummy, sells the ore in return for weapons

that

it sends to the troops stationed along the mountain

passes

near

its border with A.

Country

D, watching the interplay between A and B from its

vantage

point to the south, is carefully playing a waiting { game

} but

building

up its military strength in the meantime to keep itself safe

from

invasion by either A or B, in case one of those countries

starts

looking for a way to make an end run around the mountains

and attack

the other.

In three short paragraphs

we have described a fairly simple situation

that could produce a wide

range of consequences and

which offers several opportunities

for { adventurers } to either

defuse

or aggravate the tension.

The party might hire itself out to

any one of the four principal

countries, charged with the responsibility of

furthering that country’s

interests -- and no matter which

government they work for,

the characters are going to spend a lot

of time in the wide open

spaces and must know how to survive on

the way to accomplishing

what they are being paid to do.

Unless every character and

creature in your campaign is wearing

seven-league boots, your

world map isn’t going to be very

useful in day-to-day adventuring.

Even at the smallest recommended

scale (20 miles across the

middle of a hex), there will be

times when characters traveling

overland won’t cover the span of

a single hex in a single

day.

But it’s not the function

of a world map to mark location and

movement on a day-to-day

basis. To know precisely where characters

are and exactly what the

environment is like in their vicinity,

you need to draw up smaller-scale

maps of the areas they

MOVE through as they go

along.

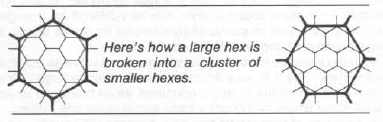

A good way to scale down

your world map is by “clustering.”

Start with a single large-scale

hex and break it up into a cluster of

eight smaller hexes (see

the accompanying diagram). On this

eight-hex cluster, make

a more detailed map of the area the large

hex covers. Since the cluster

is three hexes wide, the scale of

each smaller hex is one-third

of the scale of your world map. If

each large-scale hex is

36 miles across, then each hex in the first

cluster you create is roughly

12 miles wide. (The scale change is

not an exact 3:1 ratio,

since the hexes in a cluster are always oriented

differently from the larger

hex, but it’s close enough for our

purposes.)

Of course, each hex in a

cluster can be broken down farther;

each time you step down

in scale, reduce the distance across a

single hex to one-third

of the next larger value. If a 12-mile hex is

broken down, each hex in

the cluster is 4 miles across. If you

need to work in an even

smaller scale, just keep going: from 4

miles to 1 1/3

miles, from 1 1/3 miles to about

1/2

mile, and so on.

You don’t have to make small-scale

maps for every hex on the

world map -- at least, you

don’t have to make them all at one

time. Concentrate on the

AREA the characters are in and the AREA

they’re heading toward.

Before you sit down to begin or continue

an adventure,

be prepared with “cluster” maps of the territory

that you expect the party

to travel through, drawn up in as much

detail (as small a scale)

as you think will be necessary. If the characters

head in a direction you

didn’t expect, you can either call a

brief halt to the activities

and generate some rough small-scale

maps, or you can simply

improvise without interrupting the flow of

play. (See the text below

on the subject of “Winging It.”)

Smaller Scale, More Detail

Your large-scale world map

is a collection of generalities. That

big green spot is

a forest, hundreds or perhaps

thousands of

square miles in AREA --

but it’s not all forest. Next to it is a large

grassy plain, extending

hundreds of miles in every direction -

but it’s not just

flat terrain. Remember, your large-scale map is a

picture of the world as

it would appear to someone viewing it from

hundreds of miles overhead.

From that distance, small-scale variations

in terrain arn’t visible

-- but that doesn’t mean they’re not

there.

As you break each hex of

your world map into a cluster of

smaller-scale hexes, keep

in mind that in most cases terrain does

not remain the same on a

mile-by-mile basis. Very often, the monotony

of a flat grassland is broken

by a grove of trees several

hundred yards wide, or even

a small forest a mile or two in diameter.

If the elevation of the

land in the middle of a forest takes a

slight dip, the result might

be an area of swampy ground among

the trees. A small cliff,

perhaps only twenty or thirty feet high, can

show up almost anywhere

on otherwise flat terrain.

With each step you take to

a smaller scale, the detail of your

hex maps, and the variety

in terrain and special features they

contain, should increase.

If a river cuts through the hex that

you’re scaling down, draw

in some streams coming off the main

branch and trailing through

some of the smaller-scale hexes. If

the large-scale hex takes

in part of a lake, sketch in some

swampy ground along the

lakeshore when you go to the next

smaller scale -- a swamp

that doesn’t show up on the large-scale

map but is there nevertheless.

A DM must be able to think

on his feet. No matter

how much planning you do,

your players will occasionally have

their characters do something,

or go somewhere, you didn’t anticipate.

Sometimes this can be a

problem, but more often than

not the problem is just

an opportunity in disguise -- the opportunity

to do some creation and

decision-making on the spot, during

the

game instead of taking the time to do it later.

When characters move into

an AREA that you haven’t yet

mapped in detail, you can

do a lot more than simply say, “There’s

forest

around you as far as you can see.” Of course, that may indeed

be the case -- but it doesn’t

have to be. Remember, you’re

in control; you can improvise

and invent (within reason) any special

features that you think

will make this segment of the adventure

more interesting, or at

least give your players some things to

think about. Instead of

the simple sentence given above, you can

say something like this:

“You’re in a lightly wooded area, with

most of the trees the same

height except for one big oak a short

distance away to the east

that towers over the trees around it.

Looking north from where

you are, you can see an area where a

lot of sunlight reaches

the ground; this may be a clearing. The

land slopes upward gradually

to the west, and you can see that

the peak of this slope has

very few trees.”

By improvising like this,

you accomplish two good things. You

impress your players (whether

they realize it or not) with your organization

and attention to detail;

never mind that the detail was

created on the spur of the

moment. And, perhaps more important,

you create possibilities

for excitement and intrigue. If someone

climbs the big oak, maybe

he’ll be able to see something

important in the distance

from this vantage point. If characters

move to the clearing, maybe

they’ll find a path leading away from

it that makes it easier

for them to move through the rest of the forest.

If they climb the slope,

maybe they’ll discover that there’s a

sharp dropoff with a small

pool at the bottom. By improvising further

on what you’ve just invented,

you can make things easier or

tougher - or, in any event,

more interesting - for your players

and their characters.

The only rule to remember

when you improvise in this fashion

is that you can’t un-create

something later. Keep track of what

you tell your players, either

by making brief notes as you go or

(preferably) by sketching

the features you’ve just described on a

handy sheet of hex paper

(large,

medium,

or small).

If the characters visit this spot more <links added>

than once, they will obviously

expect to see the same details that

you described when they

first arrived on the scene. Between

playing sessions, take a

few minutes to update your collection of

small-scale maps, incorporating

the features you devised during

the game. Then you won’t

be caught short in case the characters

decide to backtrack or just

happen to stumble upon the same location

later.

As has been said many times

within the AD&D@ game books,

all the rules we can create

still provide nothing more than a

framework upon which your

world and your adventures are built.

In effect, we’ve given you

the pieces to a puzzle that has an infinite

number of different solutions.

Now it’s up to you to put those pieces together.