|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Standardization vs. Playability | Starting From Scratch | - | - | - |

Unlike most games, AD&Dis

an ongoing collection of episode adventures,

each of which constitutes a session of

play.

You, as the DM, are about to embark on

a new career, that of universe maker.

You will order the universe and direct

the activities in each game,

becoming one of the elite group of campaign

referees referred to as DMs in the vernacular of AD&D.

What lies ahead will require the use of

all of your skill,

put a strain on your imagination,

bring your creativity

to the fore,

test your patience,

and exhaust your free time.

Being a DM is no matter to be taken lightly!

Your campaign requires the above from you,

and participation by your players.

To belabor an old saw, Rome wasn't built

in a day.

You are probably just learning, so take

small

steps at first.

The milieu for initial adventures

should be kept to a size commensurate with the needs of campaign participants

--

your available time as compared with the

demands of the players.

This will typically result in your giving

them a brief background,

placing them in a settlement,

and stating that they should prepare themselves

to find and explore the dungeon/ruin they know is nearby.

As background you inform them that they

are from some nearby place where they were apprentices learning their respective

professions,

that they met by chance in an inn or tavern

and resolved to journey together to seek their fortunes in the dangerous

environment,

and that,

beyond the knowledge common to the AREA

(speech, alignments, races, and the like),

they know nothing of the world.

Placing these new participants in a small

settlement means that you need do only minimal work describing the place

and its inhabitants.

Likewise, as PCs are inexperienced,

a single dungeon

|| ruins map will suffice to begin play.

After a few episodes of play,

you and your campaign participants will

be ready for expansion of the milieu.

The territory around the settlement --

likely the "home" city || town of the

adventurers,

other nearby habitations, wilderness

areas, and whatever else you determine is right for the AREA --

should be sketch-mapped,

and places likely to become settings for

play actually done in detail.

At this time it is probable that you will

have to have a large scale map of the whole continent or sub-continent

involved,

some rough outlines of the political divisions

of the place,

notes on predominant terrain

features,

indications of the distribution of creature

types,

and some plans as to what conflicts are

likely to occur.

In short,

you will have to create the social and

ecological parameters of a good part of a make-believe world.

The more painstakingly this is done,

the more "real" this creation will become.

Eventually, as PCs develop and grow powerful,

they will explore and adventure over all

of the AREA of the continent.

When such activity begins,

you must then broaden your general map

still farther so as to encompass the whole globe.

More still!

You must begin to consider seriously the

makeup of your entire multiverse --

space, planets and their satellites, parallel

worlds, the dimensions and planes.

What is there?

Why?

Can participants in the campaign get there?

How?

Will they?

Never {fear}!

By the time your campaign has grown to

such a state of sophistication,

you will be ready to handle the new demands.

Eventually, as PCs develop and grow powerful,

they will

explore and adventure over all of the

AREA of the continent. When such

activity begins, you must then broaden

your general map still farther so as

to encompass the whole globe. More still!

You must begin to consider

seriously the makeup of your entire multiverse

-- space, planets and their

satellites, parallel worlds, the dimensions

and planes. What is there? Why?

can participants in the campaign get there?

How? Will they? Never fear! By

the time your campaign has grown to such

a state of sophistication, you

will be ready to handle the new demands.

Question: How can

I spice up my D&D game?

My players, as well as myself,

are tired of going on dungeon &&

outdoor

adventures.

I don’t have any city maps

and I really don’t want to bother with them, so what else is there left

to do?

Answer: Well, you

can ask your players what they would like to do.

They probably have all kinds

of ideas. In my campaign I had a similar

problem, and now one of

my players is trying to become Pope. So, just

ask them. I am sure they

would be more than glad to help. Remember,

they are not the enemy.

They are your friends and more than likely they

will be glad to stick their

nose into the campaign and give you their

advice. It is only human

nature to do so.

<e?>

There is nothing wrong with using a prepared

setting to start a campaign,

just as long as you are totally familiar

with its precepts and they mesh with

what you envision as the ultimate direction

of your own milieu. Whatever

doesn't match, remove from the material

and substitute your own in its

place. On the other hand, there is nothing

to say you are not capable of

creating your own starting place; just

use whichever method is best suited

to your available time and more likely

to please your players. Until you

are sure of yourself, lean upon the book.

Improvisation might be fine later,

but until you are completely relaxed as

the DM, don't run the risk of trying

to "wing it" unless absolutely necessary.

Set up the hamlet or village

where the action will commence with the

player characters entering and

interacting with the local population.

Place regular people, some

"different" and unusual types, and a few

non-player characters (NPCs) in

the various dwellings and places of business.

Note vital information

particular to each. Stock the goods available

to the players. When they

arrive, you will be ready to take on the

persona of the settlement as a

whole, as well os that of each individual

therein. Be dramatic, witty,

stupid, dull, clever, dishonest tricky,

hostile, etc. as the situation demonds.

The players will quickly learn who is

who and what is going on - perhaps

at the loss of a few coins. Having handled

this, their characters will be

equipped as well as circumstances will

allow and will be ready for their

bold journey into the dangerous place

where treasure abounds and

monsters lurk.

The testing grounds for novice adventurers

must be kept to a difficulty

factor which encourages rather than discourages

players. If things are too

easy, then there is no challenge, and

boredom sets in after one or two

games. Conversely, impossible difficulty

and character deaths cause

instant loss of interest. Entrance to

and movement through the dungeon

level should be relatively easy, with

a few tricks, traps, and puzzles to

make it interesting in itself. Features

such as rooms and chambers must be

described with verve and sufficiently

detailed in content to make each

seem as if i t were strange and mysterious.

Creatures inhabiting the place

must be of strength and in numbers not

excessive compared to the odventurers'

wherewithal to deal with them. (You may,

ot this point, refer to

the sample dungeon level and partial encounter

key.)

The general idea is to develop a dungeon

of multiple levels, and the

deeper adventurers go, the more difficult

the challenges become -

fiercer monsters, more deadly traps, more

confusing mazes, and so forth.

This same concept applies to areas outdoors

as well, with more ond

terrible monsters occurring more frequently

the further one goes away

from civilization. Many variations on

dungeon and wilderness areas are

possible. One can build an underground

complex where distance away

from the entry point approximates depth,

or it can be in o mountain where

adventurers work upwards. Outdoor

adventures can be in a ruined city or a

town which seems normal but is under a

curse, or virtually anything

which you can imagine and then develop

into a playable situation for your

campaign participants.

Whatever you settle upon as a starting

point, be it your own design or one

of the many modular settings which are

commercially available,

remember to have some overall plan of

your milieu in mind. The

campaign might grow slowly, or it might

mushroom. Be prepared for

either event with more adventure areas,

and the reasons for everything

which exists and happens. This is not

to say that total and absolutely

perfect info will be needed, but a general

schema is required.

From this you can give vague hints and

ambiguous answers. It is no

exaggeration to state that the fantasy

world builds itself, almost as if the

milieu actually takes on a life and reality

of its own. This is not to say that

an occult power takes over. It is simply

that the interaction of judge and

players shapes the bare bones of the initial

creation into something far

larger. It becomes fleshed out, and adventuring

breathes life into a make

believe world. Similarly, the geography

and history you assign to the

world will suddenly begin to shape the

character of states and peoples.

Details of former events will become obvious

from mere outlines of the

past course of things. Surprisingly, as

the personalities of player characters

and non-player characters in the milieu

are bound to develop and become

almost real, the nations and states and

events of a well-conceived

AD&D

world will take on even more of their

own direction and life. What this all

boils down to is thot once the compaign

is set in motion, you will become

more of a recorder of events, while the

milieu seemingly charts its own

course!

It is of utmost importance to some DMs

to create && design

worlds which are absolutely correct according

to the laws of the scientific

realities of our own universe. These individuals

will have to look elsewhere

for direction as to how this is to be

accomplished, for this is a rule

book, not a text on any subject remotely

connected to climatology,

ecology, or any science soft or hard.

However, for those who desire only

an interesting and exciting game,

some useful info in the way of

advice can be passed along.

Climate:

Temperature, wind, and rainfall are understood reasonobly well

by most people. The distance from the

sun dictates temperature, with the

directness of the sun's rays affecting

this also. Cloud cover also is a factor,

heavy clouds trapping heat to cause a

"greenhouse effect". Elevation is a

factor, as the higher mountains

have less of an atmosphere "blanket".

Bodies of water affect temperature, as

do warm or cold currents within

them. Likewise air currents affect temperature.

Winds are determined by

rotational direction and thermals. Rainfoll

depends upon winds and

available moisture from bodies of water,

and temperatures os well. All of

the foregoing are relevant to our world,

and should be in a fantasy world,

but the various determinants need not

follow the phsical lows of the

earth. A milieu which offers differing

climates is quite desirable because

of the variety it affords DM and player

alike.

The variety of climes allows you to offer

the whole gomut of human and

monster types to adventurous Characters.

It also allows you more creativity

with civilizations, societies and cultures.

Ecology: So many

of the monsters are large predators that it is difficult to

justify their existence in proximity to

one another. Of course in dungeon

settings

it is possible to have some in stasis or magically kept alive without

hunger, but what of the

wilderness? Then too, how do the human and

humanoid populations support themselves?

The bottom of the food chain

is vegetation, cultivated grain with respect

to people and their ilk. Large

populations in relatively small land areas

must be supported by lavish

vegetation. Herd animals prospering upon

this growth will support a fair

number of predators. Consider also the

tales of many of the most fantastic

and fearsome beasts: what do dragons eat?

Humans, of course; maidens

in particular! Dragons slay a lot, but

they do not seem to eat all that much.

Ogres and giants enjoy livestock and people

too, but at least the more intelligent

sort raise their own cattle so as to guarantee

a full kettle.

When you develop your world, leave plenty

of area for cultivation, even

more for wildlife. Indicate the general

sorts of creatures inhabiting an

area, using logic with regard to natural

balance. This is not to say that you

must be textbook perfect, it is merely

a cautionary word to remind you not

to put in too many large carnivores without

any visible means of support.

Some participants in your campaign might

question the ecology -- particularly

if it does not favor their favorite player

characters. You must be

prepared to justify it. [greengineering/education]

Here are some suggestions.

Certain vegetation grows very rapidly in

the world -- roots or tubers, a

grass-like plant, or grain. One or more

of such crops support many rabbits

or herd animals or wild pigs or people

or whatever you like! The vegetation

springs up due to a nutrient in the soil

(possibly some element unknown

in the mundane world) and possibly due

to the radiation of the sun

as well (see the slight tinge of color

which is noticeably different when

compared to Sol? . . . ). A species or

two of herbivores which grow

rapidly, breed prolifically, and need

but scant nutriment is also suggested.

With these artifices and a bit of care

in placing monsters around in the

wilderness, you will probably satisfy

all but the most exacting of players and

that one probably should not be playing

fantasy games anyway!

Dungeons likewise must be balanced and

justified, or else wildly improbable

and caused by some supernatural entity

which keeps the whole

thing running -- or at least has set it

up to run until another stops it. In any

event, do not allow either the demands

of "realism" or impossible makebelieve

to spoil your milieu. Climate and ecology

are simply reminders to

use a bit of care!

The Underground Environment: Ecology

+

TYPICAL INHABITANTS

Typical Inhabitants +

SOCIAL CLASS AND RANK IN ADVANCED DUNGEONS

& DRAGONS

Social Class and

Rank in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons +

THE TOWN AND CITY SOCIAL STRUCTURE

The Town and City Social

Structure +

There is no question that the prices and

costs of the game are based on

inflationary economy, one where a sudden

influx of silver and gold has

driven everything well beyond its normal

value. The reasoning behind this

is simple. An active campaign will most

certainly bring a steady flow of

wealth into the base area, as adventurers

come from successful trips into

dungeon and wilderness. If the economy

of the area is one which more

accurately reflects that of medieval England,

let us say, where coppers and

silver coins are usual and a gold piece

remarkable, such an influx of new

money, even in copper and silver, would

cause an inflationory spiral. This

would necessitate you adjusting costs

accordingly and then upping

dungeon treasures somewhat to keep pace.

If a near-maximum is assumed,

then the economics of the area con remain

relatively constant, and

the DM will have to adiust costs only

for things in demand or short supply

-weapons, oil, holy water, men-at-arms,

whatever.

The economic systems of areas beyond the

more active campaign areas

can be viably based on lesser wealth only

until the stream of loot begins to

pour outwards into them. While it is possible

to reduce treasure in these

area to some extent so as to prolong the

period of lower costs, what kind

of a dragon hoard, for example, doesn't

have gold and gems? It is simply

more heroic for players to have their

characters swaggering around with

pouches full of gems and tossing out gold

pieces than it is for them to have

coppers. Heroic fantasy is made of fortunes

and king's ransoms in loot

gained most cleverly and bravely and lost

in a twinkling by various means

- thievery, gambling, debauchery, gift-giving,

bribes, and so forth. The

"reality" AD&D

seeks to create through role playing is that of the mythical

heroes such as Conan, Fafhrd

and the Gray Mouser, Kothar, Elric,

and their

ilk. When treasure is spoken of, it is

more stirring when porticiponts know

it to be TREASURE!

You may, of course, adiust any prices and

costs as you see fit for your own

milieu. Be careful to observe the effects

of such changes on both play

balance and player involvement. If any

adverse effects are noted, it is

better to return to the tried and true.

It is fantastic and of heroic proportions

so as to match its game vehicle.

DUTIES,

EXCISES, FEES, TARIFFS, TAXES, TITHES, AND TOLLS

| Duties | Excises | Fees | Tariffs | Taxes |

| Tithes | Tolls | - | - | AD&&D |

| Taxes | Tax Collector | - | - | - |

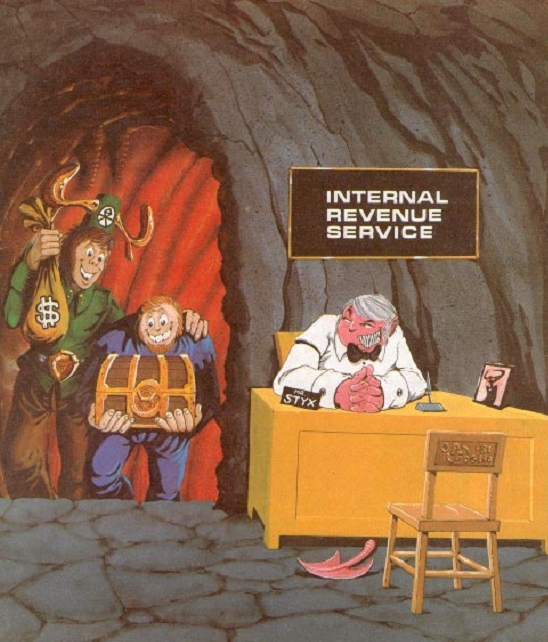

What society can exist without revenues?

What better means of assuring revenues

than taxation,

and all of the names used in the title

of this section are synonymous with taxes --

but if it is called something different

perhaps the populace won't take too much umbrage at having to pay and pay

and pay . . .

It is important in most campaigns to take

excess monies away from PCs

and taxation is one of the better means

of accomplishing this

end. The form and frequency of taxation

depends upon the locale and the

social structure.

Duties

are typically paid on goods brought into a country

or subdivision thereof, so any furs,

tapestries, etc. brought into a town for

sale will probably be subject to duty.

Excises

are typically sums paid to

belong to a particular profession or practice

a certain calling; in addition,

on excise can be levied against foreign

currency, for example, in order to

change it into the less remarkable coin

of the realm.

Fees

con be levied for

just about any reason -- entering a city

gate is a good one for non-citizens.

Tariffs

are much the same as duties, but let us suppose that this is levied

against only certain items when purchased

-- rather a surtax, or it can be

used against goods not covered by the

duty list.

Taxes

are typically paid

only by residents and citizens of the

municipality and include those sums

for upkeep of roods ond streets, walls

gates, and municipal expenses for

administration and services. Taxation

is not necessarily an annual affair,

for special taxes can be levied whenever

needful, particularly upon sales,

services, and foreigners in general.

Tithes

are principally religious taxation,

although there is no prohibition against

the combination of the

secular with the sacred in the municipality.

Thus, a tithe can be extracted

from all sums brought into the community

by any resident, the monies

going to the religious organization sponsored

by the community or to that

of the character's choosing, at your option.

(Of course, any religious

organizations within a municipality will

have to pay heavy taxes unless

they are officially recognized by the

authorities.) Tolls, finally, are sums

poid for the use of a road, bridge, ferry,

etc. They are paid according to the

numbers of persons, animals, carts, wagons,

and possibly even materials

transported.

If the Gentle Reader thinks that the taxation

he or she currently undergoes

is a trifle strenuous for his or her income,

pity the typical European populace

of the Middle Ages. They paid all of the

above, tolls being very

frequent, with those trying to escape

them by use of a byway being subject

to confiscation of all goods with a fine

and imprisonment possible also.

Every petty noble made an extraction,

municipalities taxed, and the

sovereign was the worst of all. (Eventually

merchants

banded together to

form associations to protect themselves

from such robbery, but peasants

and other commoners could only revolt

and dream of better times.) Barter

was common because hard money was so rare.

However, in the typical

fantasy milieu, we deal with great sums

of precious metals, so use levies

against player character gains accordingly.

Here is an example of a system

which might be helpful to you in developing

your own.

The town charges a 1% duty on all normal

goods brought into the place for sale --

foodstuffs, cloth and

hides, livestock, raw materials and manufactured goods.

Foreigners must also

pay this duty, but at double rate (2%).

Luxury items and precious goods -- wine,

spirits, furs, metals such as copper, gold, etc., jewelry and the like

--

pay a tariff in addition

to the duty,

a 5% of value charge

if such are to be sold,

and special forms for

sale are then given to the person so declaring his wares

(otherwise no legal

sale is possible).

Entry fee into the town is 1

copper piece per head (man or animal) or wheel for citizens,

5 coppers for non-citizens,

unless they hove official

passports to allow free entry.

(Diplomatic types have

immunity from duties and tariffs as regards their personal goods and belongings.)

Taxes are paid per head,

annually at 1 copper

for a peasant,

1 silver for a freeman,

and 1 gold piece for

a gentleman or noble;

most foreign residents

are stopped frequently and asked for proof of payment,

and if this is not

at hand, they must pay again.

In addition, a 10% sales tax is charged

to all foreigners, although no service tax is levied upon them.

Religion is not regulated by the municipality,

but any person seeking

to gain services from such an organization must typically pledge to tithe.

Finally, several tolls are extended in

order to gain access to the main route from and to the municipality --

including the route

to the dungeon, of course.

Citizens of the town must pay a 5% tax

on their property in order to defray the costs of the place.

This sum is levied annually.

Citizenship can be obtained by foreigners

after residence for one month and the payment of 10 gold pieces (plus many

bribes).

The town does not encourage the use of

foreign currency.

Merchants and other business people must

pay a fine of 5% of the value of any foreign coins within their possession

plus face certain confiscation of the coins, so they will typically not

accept them.

Upon entering the town non-residents are

instructed to go to the Street of the Money Changers in order to trade

their foreign money for the copper "cons", silver "nobs", gold "orbs",

and platinum "royals".

Exchange rate is a mere 90%,

so for 10 foreign copper pieces 9 domestic

copper "commons" are handed out.

Any non-resident with more than 100 silver

nobles value in foreign coins in his or her possession is automatically

fined 50% of their total value,

unless he or she can prove that entry

into the town was within 24 hours,

and he or she was on his or her way to

the money changers when stopped.

Transactions involving gems are not uncommon,

but a surtax of 10% is also levied against

sales or exchange of precious stones and similar goods.

Citizens of the town must pay a 5% tax

on their property in order to defray

the costs of the place. This sum is levied

annually. Citizenship can be

obtained by foreigners after residence

for one month and the payment of

10 gold pieces (plus many bribes).

The town does not encourage the use of

foreign currency. Merchants and

other business people must pay a fine

of 5% of the value of any foreign

coins within their possession plus face

certain confiscation of the coins, so

they will typically not accept them. Upon

entering the town non-residents

are instructed to go to the Street of

the Money Changers in order to trade

their foreign money for the copper "cons",

silver "nobs", gold "orbs", and

platinum "royals". Exchange rote is a

mere 90%, so for 10 foreign copper

pieces 9 domestic copper "commons" are

handed out. Any non-resident

with more than 100 silver nobles value

in foreign coins in his or her

possession is automatically fined 50%

of their total value, unless he or she

con prove that entry into the town was

within 24 hours, and he or she was

on his or her way to the money changers

when stopped. Transactions involving

gems are not uncommon, but a surtax of

10% is also levied against

sales or exchange of precious stones and

similar goods.

<>

D95.18

sales tax = 2.5% or 10% (Luxury Tax, applied

to Luxury Items)

inheritance tax = 5%

tariff = average of 1 cp for every 100

lbs. weight of goods

tolls = 1 cp per person/beast/cart or

2 cp per coach/chariot (collected at booths on certain bridges and roads)

Monthly Taxes

Market Tax = 1 cp for every adult and

every beast to enter a walled town on the monthly Market Day

Alien Tax = 1 sp per adult (resident aliens),

2 sp per adult (non-resident aliens) [diplomatic personnel are exempt from

such taxation]

Spring = Hearth Tax

simple dwelling = 1

cp; simple dwelling in town = 2 cp; simple dwelling in walled town = 6

cp; large dwelling = 1 sp; large dwelling in walled town = 3 sp; inn =

10 sp; manor = 1 gp; castle = 10 gp

Summer = Land Tax

per acre under cultivation

= 1 cp; per acre lying fallow = 0.5 cp; per acre of woodland = 0.75 cp;

per acre of barren land = 0.25 cp; per acre of pond or lake = 0.5 cp; per

acre of townland = 6 cp; per acre of fortified land = 1 sp

Summer = Nobility Tax (each family displaying

tokens of nobility pays 5 gp) <assess this to cavaliers (and other characters)

who have their own coat-of-arms?>

Autumn = The Tithe ("two shillings in

the pound on all produce, rents, and profits from the land") <assess

this to high-level characters with income from territory development> **

Autumn = Income Tax ("mostly assessed

against merchants and such" : 0.5%) <assess this merchants and those

who own their own businesses> **

Winter = Poll Tax ("assessed on every

head in the kingdom"

Adult = 2 cp; child

or marketable beast = 1 cp; riding horse = 1 sp

Winter = Magic Tax ("on all magical items")

Potion = 1 cp; scroll

= 1 sp; book = 3 sp; ring = 5 sp; wand = 10 sp; miscellaneous item = 12

sp; weapon = 1 gp; artifact or relic = 20 gp

Winter = Sword Tax ("on every edged weapon")

Sword Tax (on all edged

weapons 9 inches or more long): 1 cp for every 2 inches of edge plus 1

cp for each pound of weight

Winter = Henchmen Tax ("on all who have

retainers")

every henchman = 2

sp, every hireling = 1 sp

-

Licenses

"A pedlar's license to sell his goods

costs a penny per market day" (1 cp)

"while a beggar's license costs a penny

each season" (1 cp)

manufacturer's license = 2 gp per year

scholar who desires to operate a school

= 1 gp per year

vintners, brewers, bakers and such, monopolists

= 2 gp per year

Legal Fees and Duties

For the privelage of

bringing suit in a royal court = 10 sp (if argued in the royal court, the

King gets 10% of the amount sued for, or a min. of 30 sp, from the person

adjudged in the wrong -- in addition to what the loser must pay to the

winner, whose damages recovered are taxable as income

Harborage in any port

= 1 sp per day

To import certain items

= 20 gp

To export certain items

not at your exclusive risk = 10 gp

10 sp = "A bond of

10 shillings is required to leave the country"

15 sp = Naturalization

15 gp per year = to

practice the profession of magic-user

5 gp per year = non-humans

5 sp = to purchase

a writ from a Royal Justice

5% of profits, per

year = moneychangers and moneylenders

Fees

50 gp or so = To knight a son <apply

to cavaliers who reach the level of Knight?>

<** assessed for the year>

<>

Quote:

Originally posted by

MerricB

Gaining treasure is muchly

on the mind of my players at the moment, as they've finally reached a position

where they each want their own stronghold, whether monastary, castle, thieves'

guild or similar. And of course, such things are expensive! And I'm making

much reference to the few paragraphs in the 1E DMG about terrain clearing,

and the 3E Stronghold Builder guide for costs...

Right!

Having a base of operations

changes the whole thrust of the campaign.

Be prepared for more solo

adventures, and ready the forces of hostile NPCs to assail those places ![]()

The subject wasn't treated

in great detail by me bacuuse of lack of hands-on experience of considerable

sort.

With a mix of groups being

DMed for, the state of each was such that most were stil adventuring in

dungeons, cities, and the outdoors,

Only a few PCs had attained

sufficient wealth and level so as to look towards establishing their own

strongholds.

MONSTER POPULATIONS AND PLACEMENT

As the creator of a milieu, you will have

to spend a considerable amount

of time developing the population and

distribution of monsters -- in

dungeon and wilderness and in urban areas

as well. It is highly recommended

that you develop an overall scheme for

both population and habitation.

This is not to say that a random mixture

of monsters cannot be used,

simply selecting whatever creatures are

at hand from the tables of

monsters shown by level of their relative

challenge. The latter method

does provide a rather fun type of campaign

with a ”Disneyland” atmosphere,

but long range play becomes difficult,

for the whole lacks

rhyme and reason, so it becomes difficult

for the DM to extrapolate new

scenarios from it, let alone build upon

it. Therefore, it is better to use the

random population technique only in certain

areas, and even then to do so

with reason. This will be discussed shortly.

In general the monster population will

be in its habitat for a logical reason.

The environment suits the creatures, and

the whole is in balance. Certain

areas will be filled with nasty things

due to the efforts of some character to

protect his or her stronghold, due to

the influence of some powerful evil or

good force, and so on. Except in the latter

case, when adventurers (your

player characters, their henchmen characters,

and hirelings) move into an

area and begin to slaughter the creatures

therein, it will become devoid of

monsters.

Natural movement of monsters will be slow,

so there will be no immediate

migration to any depopulated area -- unless

some power is restocking it

or there is an excess population nearby

which is able to take advantage of

the newly available habitat. Actually

clearing an area (dungeon or outdoors

territory) might involve many expeditions

and much effort, perhaps

even a minor battle or two involving hundreds

per side, but when it is all

over the monsters will not magically reappear,

nor will it be likely that

some other creatures will move into the

newly available quarters the next

day.

When player characters begin adventuring

they will at first assume that

they are the most aggressive types in

the area -- with respect to

characters, of course. This is probably

true. You have other characters in

the area, of course, and certainly many

will be of higher level and more

capable of combatting monsters than are

the new player characters.

Nonetheless, the game assumes that these

characters have other things to

do with their time, that they do not generally

care to take the risks connected

with adventuring, and they will happily

allow the player characters

to stand the hazards. If the characters

who do the dirty work are successful,

the area will be free of monsters, and

the non-player characters will

benefit. Meanwhile, the player characters,

as adventurers, automatically

remove themselves to an area where there

are monsters, effectively

getting rid of the potential threat their

presence poses to the established

order. There is an analogy to the gunfighter-lawman

of the “Wild West”

which is not inappropriate. In some cases

the player characters will

establish strongholds nearby which will

help to maintain the stability of

the area -- thus becoming part of the

establishment. Your milieu might

actually encourage such settlement and

interaction if you favor politics in

your campaign. The depopulation and removal

to fresh challenge areas

has an advantage in most cases.

As DM you will probably have a number of

different and exciting

dungeons and wilderness and urban settings

which are tied into the whole

of the milieu. Depopulation of one simply

means that the player characters

must move on to a fresh area -- interesting

to them because i t is different

from the last, fun for you as there are

new ideas and challenges which you

desire your players to deal with. Variety

is, after all, the spice of AD&D life

too! It becomes particularly interesting

for all parties concerned when i t is

a meaningful part of the whole. As the

players examine first one facet,

then another, of the milieu gem, they

will become more and more taken

with its complexity and beauty and wish

to see the whole in true perspective.

Certainly each will wish to possess it,

but none ever will.

Variety of setting is easily done by sketching

the outlines of your world’s

“history”. Establishing power bases, setting

up conflicts, distributing the

creatures, bordering the srates, and so

forth, gives the basis for a reasoned

-- if not totally logical in terms of

our real world -- approach. The

multitude of planes and alignments are

given for such a purpose, although

they also serve to provide fresh places

to adventure and establish conflicts

between player characters as well.

Certain pre-done modules might serve in

your milieu, and you should

consider their inclusion in light of your

overall schema. If they fit smoothly

into the diagram of your milieu, by all

means use them, but always alter

them to include the personality of your

campaign so the mesh is perfect.

Likewise, fit monsters and magic so as

to be reasonable within the scope of

your milieu and the particular facet of

it concerned. Alter creatures freely,

remembering balance. Hit dice, armor class,

attacks and damage, magical

and psionic powers are all mutable; and

after players become used to the

standard types a few ringers will make

them a bit less sure of things.

Devising a few creatures unique to your

world is also recommended. As a

DM you are capable of doing a proper job

of it provided you have had

some hours of hard experience with rapacious

players. Then you will know

not to design pushovers and can resist

the temptation to develop the

perfect player character killer!

In order to offer a bit more guidance,

this single example of population

and placement will suffice: In a border

area of hills and wild forests,

where but few human settlements exist,

there is a band of very rich, but

hard-pressed dwarves. They, and the humans,

are hard pressed because of

the existence of a large tribe of orcs.

The latter have invited numbers of

ogres to join them, for the resistance

of the men and dwarves to the orcs’

looting and pillaging has cost them not

a few warriors. The orcs are gaining,

more areas nearby are becoming wilderness,

and into abandoned

countryside and deserted mines the ferocious

and dark-dwelling monsters

of wilderness and dungeon daily creep.

The brave party of adventurers

comes into a small village to see what

is going on, for they have heard that

all is not well hereabouts. With but little

help they must then overcome the

nasties by piecemeal tactics, being careful

not to arouse the whole to

general warfare by appearing too strong.

This example allows you to

develop a logical and ordered placement

of the major forces of monsters,

to develop habitat complexes and modules

of various sorts - abandoned

towns, temples, etc. It also allows some

free-wheeling mixture of random

critters to be stuck in here and there

to add uncertainty and spice to the

standard challenge of masses of orcs and

ogres. You, of course, can make

it as complex and varied as you wish,

to suit your campaign and players,

and perhaps a demon or devil and some

powerful evil clerics are in

order . . . .

Just as you have matrices for each of your

dungeon levels, prepare like

data sheets for all areas of your outdoors

and urban areas. When monsters

are properly placed, note on a key sheet

who, what, and when with regard

to any replacement. It is certainly more

interesting and challenging for

players when they find that monsters do

not spring up like weeds overnight

- in dungeons or elsewhere. Once all dragons

in an area are slain,

they have run out of dragons! The likelihood

of one flying by becomes

virtually nil. The ”frontier” moves, and

bold adventurers must move with

it. The movement can, of course, be towards

them, os inimical forces roll

over civilization. Make it all fit together

in your plan, and your campaign

will be assured of long life.

Quote:

Originally Posted by fusangite

Gary,

I'm curious: in your vision of D&D, do all the various species of monsters in the Fiend Folio, Monster Manual, etc. all exist concurrently in the same world or was it expected that most campaign worlds would have a subset of these?

An excellent question.

the plethora of critters

offered is a game device meant to keep the DM supplied with as large a

roster of strange beasts to throw at his players as was needed.

For dungeon adventuring

and really wild wilderness, such a broad variety makes sense.

For a defined world that

is less magic-heavy, then a narrower range of creatures is more logical.

In my Greyhawk campaign

something over half as many monsters as were included in the three bestiary

books were in play, the vast majority of those in dungeons or other planes.

I confess to creating new creatures in many a module just to have something confront the PCs that they didn't recognize and know how to deal with...

Cheers,

Gary

PLACEMENT OF MONETARY TREASURE

Wealth abounds; it is simply awaiting the

hand bold and strong enough to

take it! This precept is basic to fantasy

adventure gaming. Con you

imagine Fafhrd

and the Gray Mouser without a rich prize to aim for?

Conan without a pouchful of rare jewels

to squander? And are not there

dragons with great hoards? Tombs with

fantastic wealth and fell

guardians? Rapacious giants with spoils?

Dwarven mines brimming with

gems? Leprechauns with pots of gold? Why,

the list goes on and on!

The foregoing is, of course, true; but

the matter is not as simple os it might

seem on the surface. First, we must consider

the logic of the game. By adventuring,

slaying monsters or outwitting opponents,

and by gaining

treasure the characters operating within

the milieu advance in ability and

gain levels of experience. While AD&D

is not quite so simplistic as other

such games are regarding such advoncement,

it nonetheless relies upon

the principle of adventuring and success

thereat to bestow such rewards

upon player characters and henchmen alike.

It is therefore incumbent

upon the creator of the milieu and the

arbiter of the campaign, the

Dungeon Master, to follow certain guidelines

and charges placed upon

him or her by these rules and to apply

them with intelligence in the spirit

of the whole as befits the campaign milieu

to which they are being

applied.

A brief perusal of the character experience

point totols necessary to

advance in levels makes it abundantly

clear thot an underlying precept of

the game is that the amount of treasure

obtoinoble by characters is

graduated from small to large as experience

level increases. This most

certainly does not intimate or suggest

that the greater treasures should be

in the hundreds of thousonds of gold pieces

in value -- at least not in

readily transportable form in any event

-- but that subject will be discussed

a bit later. First and foremost we must

consider the placement of

the modest treasures which are appropriate

to the initial stages of a

campaign.

All monsters

would not and should not possess treasure! The TREASURE

TYPES given in the MONSTER MANUAL

are the optimums and are meant to

consider the maximum number of creatures

guarding them. Many of the

monsters shown as possessing some form

of wealth ore quite unlikely to

have any ot all. This is not a contradiction

in the rules, but an admonition to

the DM not to give away too much! Any

treasure possessed by weak,

low-level monsters will be trifling compared

to what numbers of stronger

monsters might guard. So in distributing

wealth amongst the creatures

which inhabit the upper levels of dungeons/dungeon-like

areas, as well

as for petty monsters dwelling in small

numbers in the wilderness, assign it

accordingly. The bulk of such treasure

will be copper pieces and silver.

Perhaps there will be a bit of ivory or

a cunningly-crafted item worth a few

gold pieces.

Electrum will be most unusual, gold rare,

and scarcer still will be a platinum

piece or a small gem! Rarest of all, treasure

of treasures -- the magic

item - is detailed hereafter (PLACEMENT

OF MAGIC ITEMS). If some

group of creatures actually has a treasure

of 11 gold pieces, another will

have 2,000 coppers and yet a third nothing

save a few rusty weapons. Of

course, all treasure is not in precious

metals or rare or finely made substances.

Is not a suit of armor of great value?

What of a supply of oil? a vial

of holy water? weapons? provisions? animals?

The upper levels of a dungeon

need not be stuffed like a piggy bank

to provide meaningful treasures

to the clever player character.

Assign each monster treasure, or lack thereof,

with reason. The group of

brigands has been successful of late,

and each has a few coppers left from

roistering, while their leader actually

has a small sum of silver hid away coupled

with salvaged armor, weapons, and any

odd supplies or animals

they might have around. This will be a

rich find indeed! The giant rats have

nothing at all, save a nasty, filthy bite;

but the centipedes living beneath a

pile of rotting furniture did for an incautious

adventurer some years ago,

and his skeletal remains are visible still,

one hand thrust beneath the

debris of the nest. Hidden from view is

a silver bracelet with an agate, the

whole thing being valued at 20 gold pieces.

Thus, intelligent monsters, or

those which hove an affinity for bright,

shiny objects will consciously

gather and hoard treasures. Others will

possibly have some as an

incidental remainder of their natural

hunting or self-defense or aggressive

behavior or whatever. Naturally, some

monsters will be so unfortunate as

to have nothing of value at all, despite

their desire to the contrary - but

these creatures might know of other monsters

(whom they hate and envy)

who do have wealth!

In more inaccessible regions there will

be stronger monsters -- whether

due to numbers or individual prowess is

immaterial. These creatures will

have more treasure, at least those with

any at all. Copper will give way to

silver, silver to electrum, electrum to

gold. Everyday objects which can be

sold off for a profit -- the armor and

weapons and suchlike -- will be

replaced by silks, brocades, tapestries,

and similar items. Ivory and spices,

furs and bronze statues, platinum, gems

and jewelry will trickle upwards

from the depths of the dungeon or in from

the fastness of wilderlands. But

hold! This is not a signal to begin throwing

heaps of treasure at players as

if you were some mad Midas hating what

he created by his touch. Always

bear in mind the effect that the successful

gaining of any treasure, or set of

treasures, will have upon the player characters

and the campaign as a

whole. Consider this example:

A pair of exceedingly large, powerful and

ferocious ogres has taken up

abode in a chamber at the base of a shaft

which gives to the land above.

From here they raid both the upper lands

and the dungeons roundabout.

These creatures have accumulated over

2,000 g.p. in wealth, but it is obviously

not in a pair of 1,000 g.p. gems. Rather,

they have gathered an assortment

of goods whose combined value is well

in excess of two

thousand gold nobles (the coin of the

realm). Rather than stocking a

treasure which the victorious ployer characters

can easily gather and carry

to the surface, you maximize the challenge

by making it one which ogres

would naturally accrue in the process

of their raiding. There are many

copper and silver coins in a large, locked

iron chest. There are pewter

vessels worth a fair number of silver

pieces. An inlaid wooden coffer,

worth 100 gold pieces alone, holds a finely

wrought silver necklace worth

an incredible 350 gold pieces! Food and

other provisions scattered about

amount to another hundred or so gold nobles

value, and one of the ogres

wears a badly tanned fur cape which will

fetch 50 gold pieces nonetheless.

Finally, there are several good helmets

(used as drinking cups), a

bardiche, and a two-handed sword (with

silver wire wrapped about its hilt

and a lapis lazuli pommel to make it worth

three times its normal value)

which complete the treasure. If the adventurers

overcome the ogres, they

must still recognize all of the items

of value and transport them to the

surface. What is left behind will be taken

by other residents of the netherworld

in no time at all, so the bold victors

have quite a task before them. It

did not end with a mere slaying of ogres

. . . .

In like manner the hoard of a dragon could

destroy a campaign if the

treasure of Smaug, in THE HOBBIT,

were to be used as an example of what

such a trove should contain. Not so for

the wise DM! He or she will place a

few choice and portable items, some not-so-choice

because they are

difficult to carry off, and finally top

(or rather bottom and top) the whole

with mounds, piles, and layers of copper

pieces, silver, etc. There will be

much there, but even the cleverest of

players will be more than hard put to

figure out a way to garner the bulk of

it after driving off, subduing, or

slaying the treasure's guardian. Many

other avaricious monsters are

eagerly awaiting the opportunity to help

themselves to an unguarded

dragon hoard, and news travels fast. Who

will stay behind to mind the

coins while the rest of a party goes off

to dispose of the better part of the

loot? Not their henchmen! What a problem

. . .

In the event that generosity should overcome

you, and you find that in a

moment of weakness you actually allowed

too much treasure to fall into

the players' hands, there are steps which

must be taken to rectify matters.

The player characters themselves could

become attractive to others

seeking such gains. The local rulers will

desire a shore, prices will rise for

services in demand from these now wealthy

personages, etc. All this is not

to actually penalize success. It is a

logical abstraction of their actions, it

stimulates them to adventure anew, and

it also maintains the campaign in

balance. These rules will see to it that

experience levels are not gained too

quickly as long as you do your part as

DM!

Quote:

Originally Posted by Quasqueton![]()

Mr. Gygax,

I've got a question based on two observations about AD&D1.

1- In looking back through some old official D&D adventure modules, I see the treasure awards were usually very high -- many thousands of gp worth of treasure (not counting magic items).

2- The AD&D1 rules called for some pretty hefty training costs to level up.

My question:

Which came first? Was the confiscatory training costs an answer to strip away all that treasure given in the adventure modules, or was the level of treasure given in adventure modules increased to cover the cost of training?

Thanks, and Merry Christmas.

Quasqueton

Yuletide Salutations Quasqueton

Gaining lots of treasure

is something I always favored.

To keep it moving I encouraged

players to have their PCs hire many retainers, troops, build a castle,

etc.

When that failed to keep

them seeking more wealth the trainig costs and other cash-draining devices

were added into the game.

Christmas cheer,

Gary

Just as it is important to use forethought

and consideration in placing

valuable metals and other substances with

monsters or otherwise hiding

them in dungeon || wilderness, the placement

of magic items is a serious

matter. Thoughtless placement of powerful

magic items has been the

ruination of many a campaign. Not only

does this cheapen what should be

rare and precious, it gives player choracters

undeserved advancement and

empowers them to become virtual rulers

of all they survey. This is in part

the fault of this writer, who deeply regrets

not taking the time and space in

D&D

to stress repeatedly the importance of moderation. Powerful magic

items were shown, after all, on the tables,

and a chance for random

discovery of these items was given, so

the uninitiated DM cannot be

severely faulted for merely following

what was set before him or her in

the rules. Had the whole been prefaced

with an admonition to use care

and logic in placement or random discovery

of magic items, had the

intent, meaning, and spirit of the game

been more fully explained, much

of the give-away aspect of such campaigns

would have willingly been

squelched by the DMs. The sad fact is,

however, that this was not done, so

many campaigns are little more than a

joke, something that better DMs

jape at and ridicule -- rightly so on

the surface -- because of the foolishness

of player characters with astronomically

high levels of experience

and no real playing skill. These god-like

characters boast and strut about

with retinues of ultra-powerful servants

and scores of mighty magic items,

artifacts, relics adorning them as if

they were Christmas trees decked out

with tinsel and ornaments. Not only are

such "Monty Haul" games a crashing

bore for most participants, they are a

headache for their DMs as well,

for the rules of the game do not provide

anything for such play -- no

reasonable opponents, no rewards, nothing!

The creative DM can, of

course, develop a game which extrapolates

from the original to allow such

play, but this is a monumental task to

accomplish with even passable

results, and those attempts I have seen

have been uniformly dismal.

Another nadir of Dungeon Mastering is the

"killer-dungeon" concept.

These campaigns are a travesty of the

role-playing adventure game, for

there is no development and identification

with carefully nurtured player

personae. In such campaigns, the sadistic

referee takes unholy delight in

slaughtering endless hordes of hapless

player choracters with unavoidable

death traps and horrific monsters set

to ambush participants as soon as

they set foot outside the door of their

safe house. Only a few of these

"killer dungeons" survive to become infamous,

however, as their

participants usually tire of the idiocy

after a few attempts at enjoyable

gaming. Some lucky ones manage to find

another, more reasonable,

campaign; but others, not realizing the

perversion of their DM's campaign,

give up adventure gaming and go back to

whatever pursuits they followed

in their leisure time before they tried

D&D.

AD&D

means to set right both extremes. Neither the giveaway game nor

the certain death campaign will be lauded

here. In point of fact, DMs who

attempt to run such affairs will be drumming

themselves out of the ranks of

AD&D

entirely. ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS aims at providing

not only the best possible adventure game

but also the best possible

refereeing of such campaigns.

Initial placement of magic items in dungeon

and wilderness is a crucial

beginning for the campaign. In all such

places you must NEVER allow

random determination to dictate the inclusion

of ANY meaningful magic

items. Where beginning/low-level player

characters are concerned, this

stricture also applies to the placement

of any item of magic. Furthermore,

you need never feel constrained to place

or even allow any item in your

campaign just because it is listed in

the tables. Certainly, you should never

allow a multiplicity, or possibly even

duplication, of the more powerful

items. To fully clarify this, consider

the development of a campaign as

follows:

In stocking the setting for initial play

in the campaign, you must use great

care. Consider the circumstances of the

milieu and the number of player

characters who will be active in it. Then,

from the lists of possible items,

choose a selection which is commensurate

with the setting and the

characters involved. For example, you

might opt for several potions, a

scroll of 1 spell, a wand, a pair of boots

of elvenkind, several + 1 magic

arrows, and a + 1 magic dagger. As these

items will be guarded by

relatively weak creatures, you will allow

only weak items. The potions will

be healing, heroism, levitation or the

like. The spell on the scroll will be

low level -- first or second. If you do

decide placement of the wand is appropriate,

you will make certain that its guardian

will use it in defense,

and the instrument will have few charges

left in any event, with a power

which is not out of line with the level

of the characters likely to acquire it.

The magical boots will be worn by a denizen

of the area. While the magic

arrows might not be used against adventurers,

the + 1 dagger will be.

With all this in mind, you place the items

in the countryside and first/upper

level of the dungeon/dungeon-like setting.

You never allow more than a

single item or grouping (such as 3 magic

arrows) to a treasure, nor more

treasures with magic items than 1 in 5

to 1 in 10, as this is an initial adventuring

setting.

As the campaign grows and deeper dungeons

are developed, you

exercise the same care in placement of

selected and balanced magic

items. Of course, at lower levels of the

dungeon you have more powerful

single items or groupings of disparate

items, but they are commensurate

with the challenge and ability of participants.

Guardians tend to employ

the items routinely, and others are hidden

ingeniously to escape detection.

Likewise in the expanding world around

the starting habitation you place

monsters and treasures, some with magic.

You, the DM, know what is

there, however, as you have decided what

it will be and have put it there

for a purpose -- whether for the overall

direction of the campaign, some

specific task, or the general betterment

of player characters to enable

them to expand their adventuring capabilities

because they are skillful

enough to face greater challenges if they

manage to furnish themselves

with the wherewithal to do so.

In those instances where a randomly discovered

monster has a nearby lair,

and somehow this lair contains treasure,

do not allow the dice to dictate a

disaster for your campaign. If their result

calls for some item of magic

which is too powerful, one which you are

not certain of, or one which you

do not wish to include in the game at

this time, you will be completely

justified in ignoring it and rolling until

a result you like comes up, or you

can simply pick a suitable item and inform

the players that this is what they

found. It is only human nature for people

to desire betterment of their

position. In this game it results in player

characters seeking ever more

wealth, magic, power, influence, and control.

As with most things in life,

the striving after is usually better than

the getting. To maintain interest and

excitement, there should always be some

new goal, some meaningful

purpose. It must also be kept in mind

that what is unearned is usually unappreciated.

What is gotten cheaply is often held in

contempt. It is a great

responsibility to Dungeon Master a campaign.

If you do so with intelligence,

imagination, ingenuity, and innovation,

however, you will be well

rewarded. Always remember this when you

select magic items for placement

as treasure!

SA:

Is it OK for a DM to deliberately kill characters who have too many magic

items ?

Q: Can a DM give away

magical items in an adventure

and then later say that

the items operate at reduced effectiveness

or have wholly new powers?

A: It may be that

the DM had planned ahead that certain magic

items would indeed change

their abilities over time (a wand of wonder,

for instance, constantly

does unpredictable things), but

often DMs alter magical

items as a way of bringing the campaign

back into order if they

find they've given away some powerful

items that are too tough

to manage. This is not a good way

of handling the situation,

since it does violate the spirit of the

rules, but it is one way

to handle things. It would be better to set

up situations working within

the rules than to arbitrarily say,

"Well, your +4 sword is

now a +1 sword." Players will accept

changes done within the

rules better than if they feel (and rightly

so) that they are getting

rooked.

(76.62)

THE FORUM

PLACEMENT OF MAGIC ITEMS

I have seen several AD&D

game campaigns

die in their infancy. The

reason for failure in

each case was ignorance

and inexperience on

the part of the DM; he just

did not understand

what magic items are appropriate

for low-, mid-,

and high-level characters.

He allowed the infant

campaign to succumb to the

dread disease of

Monty Haulitis. Low-level

characters became

more like comic-book heroes,

with items such as

a ring of invisibility/inaudibility,

a vorpal sword,

or a wand of frost with

80 charges. The inexperienced

DM cannot be blamed for

his foolishness;

there is a chance shown

for these items on

the tables, and wands are

stated to have 80 to

100 charges when found.

Play at this level of

power becomes meaningless

because there are

no suitable opponents. Participants

lose interest

and the fledgling campaign

dies.

Rearranging the magic item

tables in the second

edition of the Dungeon

Master’s Guide could at

least partially remedy this

problem. Rather than

arranging the tables according

to type of item (i.e.,

rings, swords, misc. magic,

etc.), they should be

arranged according to the

power of the item (i.e.,

appropriate 1st-3rd level

items, appropriate 4th-6th

level items, etc.). This

would probably involve

creating a new meaning of

the word ?level? (oh,

no!), meaning the power

of a magic item. Under a

system such as this, a DM

would need a wisdom of

3 to allow his campaign

to fall victim to the curse

of Monty Haul.

Brock Sides

Moscow TN

(Dragon

#124)

Rhuvein wrote:

I will heed your advice

and let the adventurers find it in the way you suggest. 8)

Many thanks,

Regards,

Rhuvein.

Heh!

that's the sirit. make those

lazy PC go out and risk life and limb to gain magical goodies. None of

that namby-pamby purchasing or forging such items on their own. That's

for sissy new D&D players ![]()

Cheers,

Gary

Bombay wrote:

Gary, what are your thoughts

on the ratio of magic items in a party?

I have been running my own game, and have used the ratio of 1 per 2 levels approx.

Thus these guys are 6th - 8th level, and they have 3-4 magic items(Excluding scrolls and potions.)

Is there a ratio you like

to use?

Sorry, but I missed this

before ![]()

That seems to be a good rule of thumb, although after 10th level I would expect it to rise to 1 per level for magic-users.

Cheers,

Gary

Quote:

Originally Posted by Delta

Gary, how many magic items

did you normally see on a name level (for example) PC in your D&D games?

I thought to ask as I looked at some of the classic AD&D adventures. With the 1981 printing of "Against the Giants", the "Caution" note says PCs should come with 2 or 3 magic items. But the "Original Tournament Characters" at the end have between 5 and 11 magic items each.

So what would you expect for PCs of this level: 2-3? Half-a-dozen? 10 or more magic items?

Who cares?

If the PCs are walking magic shope, the encounters get beefed up accordingly.

However...

Mordie has about six or seven he carries with him at all times, mainly things to up his AC and number of spells on tap.

Potions and scrolls count as only half or less of a normal, reusable item.

Cheers,

Gary

Quote:

Originally Posted by Delta

Gary, thanks for the insight.

Welcome, and trust that

you understood the opening of my response. The GM should not worry about

limiting PCs' equippage of magical sort, merely manage it through "adjusted"

encounters...

Cheers,

Gary

Quote:

Originally Posted by rossik

like what, mr gygax?

Potions and scrolls as appropriate,

those mainly of the healing sort. When magic items of greater value are

in order, keep them low initially, and only as the PCs eise in level should

the power of such objects rise--say at 4th level, 8th level, 12th level,

etc.

Watch out giving potent magic items to NPCs and monsters to use, for the PCs usually end up with them.

Cheers,

Gary

Quote:

Originally Posted by Odnasept

Edena's tale of the constantly-doubling

experience awards reminds me of one of my favourite mistakes in AD&D,

made when I was but fourteen:

One of my players of similar age played a Mage named (uncreatively but surprisingly-appropriately) Merlin, and made liberal use of a necklace he had acquired around 9th or 10th level which contained five charges of a homebrewed 9th Level spell called Michelle's Chaos Wind (similar to a Finger of Death capable of effecting multiple targets). With this he killed more than one quasi-/demi-deity (unlucky saves on their part) and I, lacking official XP values for such things, decided to go the rout of impressing said player with progressively ludicrously high numbers.

Looking back at the character sheet a few years later, while I am not sure if I actually awarded a trillion or more XP, I calculated from what it looked like on that oft-erased area of the sheet and determined that he could be of around 6,053,008th level. I am glad that while we were playing I ruled that noone was available who could train Merlin beyond 20th level, but I would be very interested in knowing how Gary would handle a campaign with PCs of seven-digit level (I suspect remarkably well, but I am curious as to what kinds of challenges would be faced by said PCs).

A cautionary lesson for

all DM there.

As a natter of fact i fell into the trap of excell XP awards back in late 73 and realized it soon enough to redredd the problem, adjust for levels too easily gained by making the next few doubly hard to attain.

Excell magic items are easily managed though, mainly through attack forms what require them to save ot be destroyed, or areas where they have a chance of losing their enchantment.

Cheerio,

Gary

Cheers,

Gary

Hi Haakon1,

As a general rule I select the magic items to be discovered in a set encounter, use random table determination for all treasure in a random encounter.

On occasion I will have a

real magic item for sale, or available as a gift if a PC or PCs do the

prescrubed things correctly.

ANy item that can be purchased

is of very minimal magic--mostly some minor healing or a +1 arrow for example.

Dealers in "magic" in my campaign settings are generally swindlers, and that makes it doubly hard for players when they come across an NPC that is offering something not a fake.

Cheers,

Gary

TERRITORY DEVELOPMENT BY PLAYER CHARACTERS

When PCs reach upper levels and decide

to establish a

stronghold and rule a territory, you must

have fairly detailed information

on hand to enable this to take place.

You must have a large scale map

which shows areas where this is possible,

a detailed cultural and social

treatment of this area and those which

bound it, and you must have some

extensive information available as to

who and what lives in the area to be

claimed and held by the player character.

Most of these things are

provided for you, however, in one form

or another, in this work or in the

various playing aid packages which are

commercially available. The exact

culture and society of the area is up

to you, but there are many guides to

help you even here.

Assume that the player in question decides

that he will set up a stronghold

about 100 miles from a border town, choosing

an area of wooded hills as

the general site. He then asks you if

there is a place where he can build a

small concentric castle on a high bluff

overlooking a river. Unless this is

totally foreign to the area, you inform

him that he can do so. You give him

a map of the hex where the location is,

and of the six surrounding hexes.

The player character and his henchmen

and various retainers must now go

to the construction site, explore and

map it, and have construction

commence.

If you have not already prepared a small

scale map of the terrain in the

area, use the random generation method

when the party is exploring.

Disregard any results which do not fit

in with your ideas far the place. Both

you and the player concerned will be making

maps of the territory -- on a

scale of about 200 yards per hex, so that

nine across the widest part will

allow the superimposition of a large hex

outline of about one mile across.

Use actual time to keep track of game

time spent exploring and mapping

(somewhat tedious but necessary). Check

but once for random monsters in

each hex, but any monster encountered

and not driven off or slain will be

there from then on, excepting, of course,

those encountered flying over or

passing through. After mapping the central

hex and the six which surround

it, workers can be brought in to commence

construction of the castle. As

this will require a lengthy period of

game time, the player character will

have to retain a garrison on the site

in order to assure the safety of the

crew and the progress of the work (each

day there will be a 1 in 20 chance

that a monster will wander into one of

the seven hexes explored by the

character, unless active patrolling in

the territory beyond the area is

carried on).

While the construction is underway, the

character should be exploring and

mapping the terrain beyond the core area.

Here the larger scale of about

one mile per hex should be used, so that

in all the character can explore

and map an entire campaign hex. There

are MANY one mile hexes in a 30

mile across campaign hex, so conduct movement

and random monster

checks as is normal for outdoor adventuring.

Again, any monsters encountered

will be noted as living in a hex, as appropriate,

until driven out

or killed. However, once a hex is cleared,

no further random monster

checks will be necessary except as follows:

1) Once per day a check

must be made to see if a monster has

wandered into one of

the border hexes which are adjacent to unexplored/

uncleared lands.

2) Once per week a check

must be made to see if a monster has

wandered into the central

part of the cleared territory.

Monsters which are indicated will generally

remain until driven out or slain.

Modifiers to this are:

1) Posting and placement

of skulls, carcasses, etc. to discourage intelligent

creatures and monsters

of the type able to recognize that the

remains are indicative

of the fate of creatures in the area.

2) Regular strong patrols

who leave evidence of their passing and aggressively

destroy intruders.

Organized communities whose presence and

militia will discourage all but organized groups who prey on them or certain

monsters who do likewise.

Assuming that the proper activity is kept

up and the castle is finished, then

the player character and entourage can

take up residence in the stronghold.

By patrolling the territory regularly

-- about once per week on a

sweep basis, or daily forays to various

parts of the area, the character will

need only check once each week for incursions

of wandering monsters

(see APPENDIX C: RANDOM MONSTER ENCOUNTERS)

on the Uninhabited/

Wilderness table. Checks must also

be made on the Inhabited

table. If no road goes through the territory,

then but one such check per

week is necessary. If a road goes through,

then three checks per week

must be made on the Inhabited table.

(This can be profitable if the encounters

are with merchants and pilgrims,

less so with certain other types . . .

.)

At such time as a territory has more than

30 miles of inhabited/patrolled

land from center to border, then only

the second type of monster checks

are made, and all unfavorable ones, save

one per month, are ignored.

This reflects the development of civilization

in the area and the shunning

by monsters of the usual sort -- things

such as ankheg might love it, however,

and bandits may decide to make it a regular

place of call. As usual,

any monsters not driven off or slain will

settle down to enjoy the place. If

regular border patrols are not kept up,

then the territory will revert to

wilderness status -- unless the lands

around it are all inhabited and

patrolled. In the latter case all of the

unsavory monsters from the surrounding

territory will come to make it a haven

for themselves.

Because this is a fantasy adventure game,

it is not desirable to have any

player character's territory become tame