| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dungeons & Dragons | Advanced Dungeons & Dragons | - | Dragon magazine | The Dragon #36 |

In the June 1979 issue of The Dragon (#26), Rick Krebs described

a microcomputer-based system designed

to assist the DM in the more

mundane details of running his campaign. He characterized himself as

“by no stretch of the IMAGINATION a computer scientist, merely a gamer

looking for new ways to USE technology in gaming.” Let me give you

the

viewpoint of 1 computer scientist who has recently discovered

gaming.

The computer is merely a tool. Although it can execute millions of

instructions each second, it can only perform tasks which have been

explained to it in agonizing detail. It is therefore notably lacking

in

creativity. Almost by definition, anything which we understand well

enough to program into a computer is not creative. (The predictions

of a

super chess-playing program, for instance,

have yet to be fulfilled. The

AI researchers discovered that we do not know how

human experts play championship chess.

There are programs which are

excellent chess players, but the top players are still human.) Those

tasks

which we understand fully-especially repetitious clerical tasks—can

often be performed more quickly and accurately by the computer than

by humans. The computer is the ideal drudge.

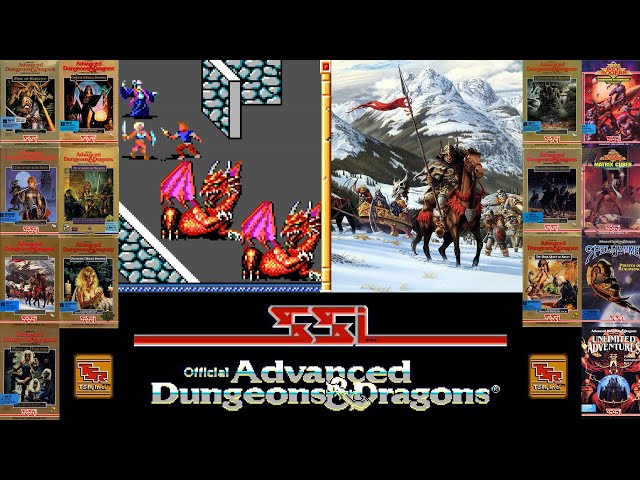

In the realm of AD&D, a computer can

perform many dull housekeeping

chores so that the DM may concentrate on the creative aspects

of his task. AI research has taught us how to organize

goal-directed games. Computer simulation techniques used in engineering

and economics allow a changing world to

be modeled within

the computer. (See “Zork A Computerized Fantasy Simulation Game”

in the April 1979 issue of Computer. Zork is like single-player

D&D

without role-playing or campaign

background.) Let us consider 8 of

the DM’s tasks and the ways in which standard computer science

techniques might simplify them:

1st, the DM describes the players’ immediate environment to

them. Keeping track of the dungeon map, the

players’ positions on it,

and any changes to the dungeon (forced doors, etc.) is trivial for

the

computer. In fact, a schematic display of the visible room and corridor

layout could be maintained by the computer.

2nd, the DM enforces (or fails to enforce because they are too

much bother) restrictions on Time and

movement.

The inventory of

items carried by each player and their

effect on movement can be

maintained by the computer. Various time-related limitations such as

torch consumption, REST periods, healing,

and spell duration are easily

monitored if the computer is keeping The

Game’s master clock.

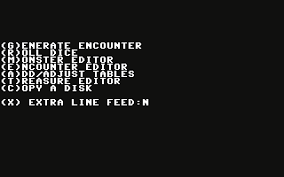

3rd, probabilistic outcomes (combat

results, saving throws, wandering

monsters, etc.) decided by the DM depend upon dice throws and

tables. It is easy to program a random-number generator to simulate

any

combination of dice; all the many tables (combat,

armor,

etc.) may be

stored in the computer. This would SPEED up melee

immensely.

4th, the DM is responsible for unintelligent monsters

and subservient

allies and hirelings. Those monsters

and NPCs

who simply attack, retreat, or follow orders can be controlled by the

computer. (A gelatinous cube

does not require much attention from the

DM during an encounter. )

5th, the DM operates the intelligent monsters

and NPCs.

When negotiation, trickery, or flexible response are required,

the DM draws on decades of social experience which cannot be

programmed into any computer. Given the numerical information from

the Monster Manual, however, the

computer can randomly generate

monsters or henchmen and keep track

of their HP while the DM

directs their behavior. Like other tabular information, the monster

characteristics need only be entered once when the program is written.

Variations can be made at any time at the DM’s discretion, of course.

6th, the DM designs the layout of the dungeon and places treasures,

traps, and monsters within it All of these can be generated

randomly under constraints imposed by the DM (total size, average

corridor length, average treasure value and monster strength for each

level, etc. ). For the solo player, automatic dungeon creation would

be a

real boon. Unfortunately, a machine-created dungeon lacks the fiendish

ingenuity provided by a human DM. In practice, I would expect the DM

to design critical areas and let the computer flesh out the dungeon

or to

edit a randomly generated dungeon to create a more interesting setting.

As users of office word-processing equipment know, just having information

stored in the computer makes it infinitely easier to change

things—especially if you have a video display screen.

Seventh, the DM must create the culture and terrain in which the

campaign takes place. Not having read Tolkien, Leiber, or Vance, a

computer can contribute little here besides randomly generated names.

(Computers can tell stories or converse like Freudian analysts, but

they

usually do it by randomly selecting items from their limited store

of

cliches. Just like humans, when they have no real knowledge of a

subject they resort to b.s. )

Eighth, the DM is the referee and final arbiter for the campaign. The

computer can keep track of monsters killed and treasure gained, but

all

advancement decisions and player disputes requiring judgment are the

responsibility of the DM.

The computer can take over many burdensome and repetitious

housekeeping chores, thereby speeding up play and freeing the DM for

his more challenging and creative tasks. One interesting possibility

is

that with enough help from the computer the DM might be far less

reluctant to let the party split up temporarily. At present it is not

really

practical for the DM to run several scenarios at once. There are also

very

good reasons discussed in the AD&D manuals why splinter

groups may

be bad for the campaign. If, however, those leaving (or cut off from)

the

main party are willing to accept less of the DM’s personal attention,

the

computer may be able to keep their part of the dungeon operating until

they are reunited with their fellows.

So why don’t I have all these wonderful aids running in my living

room? The answer is money, of course. Rick Krebs somehow managed

to shoehorn his program and tables into a microcomputer with only

4,096 characters of memory. His program was written in BASIC, a

programming language too weak for an extensive project His microcomputer

cost a few thousand dollars at most In contrast, artificial

intelligence programs are usually run in a sophisticated language,

such

as LISP, on a machine having hundreds of thousands of characters of

memory and costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. This means that

the sophisticated techniques which are the fruits of decades of research

are not applicable to a machine that the average gamer or group of

gamers can afford.

The situation is improving rapidly, however. The next generation of

microcomputers will sell for a few thousand dollars but have most of

the

capabilities of the previous generation of large computers. Sophisticated

languages such as Pascal and LISP, formerly available only on large

machines, are now available even on microcomputers. There is a

growing realization that a microcomputer can do almost anything a large

machine can do—only more slowly. Since a significant percentage of

computer science students have grown up on fantasy and science

fiction, you can expect to see some very powerful AD&D aids

in the next

few years.

As an example of what can be done now, consider the problem of

describing the adventurers’ surroundings to them. Ideally, one might

like to display the visible area of the dungeon, the adventurers, and

the

monsters on a color television screen. Realistically, enough resolution

to

draw the characters well and enough speed to allow even cartoon-like

movement are prohibitively expensive. Painted figures give much more

realism than could be afforded with a fully animated dungeon.

Nevertheless, available displays do have enough resolution to easily

depict the rooms and corridors, if not the characters and items within

them. The Apple II microcomputer, for example, has a simple color

graphics capability. An option allows display on any color television.

Large-screen projection televisions have been available for years now.

Why not place standard painted figures in their marching order on a

table and project the dungeon around them? As the adventurers move

through the dungeon, the projection could be made to advance and

turn around the stationay miniatures. Special mounting would be

needed to direct the projection onto the horizontal surface, but the

whole system could be bought for less than the price of a car. Its

two

major components, the microcomputer and the television, would be

available for their normal functions. Having a clear visual display

of the

adventurers’ surroundings would enhance the realism of the fantasy.

Retaining the use of miniatures would preserve that artistic aspect

of

gaming, as well as keep the system cost within bounds.

Although we can expect some fantastic playing aids in the near

future, a note of caution is in order. Since the computer is intended

to be

the DM’s assistant, the interface between DM and computer must be

very carefully designed. If the DM spends all of his Time

typing data into

the machine and muttering at his private DISPLAY screen, the players

will

become bored and leave. The computer must be FAST, unobtrusive, and

completely subservient to the DM.

OUT ON A LIMB

‘Computer freak’

To the editor:

I have just purchased TD #36 and I fell that it

is time I wrote and told you how much I enjoy the

magazine. I especially like the new series, The

Electric Eye. As a computer freak and a game

freak I can see how the two go together so well.

I think an article on the more unusual weapons

would be interesting. There are several

that I would like to see in our campaign such as a

bola, net, garotte, whip, boomerang, etc.

Is there an updated version of the Monster

Manual in the works? Or at least

a collection of

the new monsters from Dragon’s Bestiary? The

latest, the Krolli, is a beauty.

Michael E. Stamps

(The Dragon #39)

According to our recently compiled index of

all TD articles (to be published in TD-40),

there

has not been a “table of bonuses jot each monster”

printed in the magazine. Michael’s friend

may be referring to the alphabetical list of creatures

from the Monster Manual which

is printed

as an appendix in the Dungeon Masters

Guide. <this data has been moved to the MM>

As for Michael’s request for an article on unusual

weapons, all we can do is pass on that sentiment

(by publishing this letter) and hope that some

energetic reader will take advantage of the opportunity

to send us an article on that subject.

Yes, there is another monster book in the

works. The Fiend Folio is being

produced by

TSR Hobbies, Inc., and will be available later <TSR UK>

this year. The project is out of The Dragon’s

domain, so we can’t say exactly what it will contain.

At the present time, we have no plans to

reprint Bestiay creations in a single volume—

but who knows what the future will hold?

—Kim

(The Dragon #39)