"[As] the thief, the male and the female, amputate their hands in

recompense for what they committed as a detterant [punuishment] from Allah.

And Allah is Exalted in Might and Wise."

- Quran/5/38

| Dragon #65 | - | - | Dragon magazine | |

| - | - | AD&&D | - | - |

| Dungeons & Prisons | - | - | - | - |

Know, O traveller, that caravan

fees

are high for a good reason: such

overland

travel is dangerous. Travel in

any

place is unsafe if one knows

not local

laws and those things which underlie

them. Fair speech from a survivor

should

not be taken ill. Wherefore.

. .

Adventurers in an AD&D™

world may

meet a fascinating variety of governments,

beliefs, and customs if they travel.

Too often, however, one kingdom

seems just like another; all play occurs

in

a quasi-feudal society that is perhaps

best described as “romantic medieval,”

spiced with enough individual freedom

to account for widespread trade, party

and individual adventuring, strife, and

the bearing of arms. This is fun and not

in

itself bad, but it can breed monotony and

robs a world of the depth and color

which is born of making the atmosphere

and society of (in my Forgotten Realms

campaign) the imperial city of Waterdeep

different from the serene, rustic

beauty of Deepingdale far inland.

Religion, politics, customs, government,

laws and their enforcement; all are

linked in describing a society and should

be considered together. The Dungeon

Masters Guide notes (under “Duties,

Excises,

Fees,

Tariffs, Taxes, Tithes, And

Tolls”

at p.90) those taxes and eccentric

local (read: nuisance) laws that travelers

often run into problems with, and indeed

these are generally most important in

play — but they should not be devised or

altered in isolation. A DM must always

ponder the effects of a law or a legal

change, considering all of the elements

listed above which are linked to it. No

one set of “basic” or cornerstone laws

can be offered in an article such as this;

each DM must evolve a system that

matches the elements as they are in the

various kingdoms of his or her own

world. What can be of help is a brief tour

of the elements involved.

Every land has its laws — whether they

are a code laid down by a court, the decree

decree of a ruler, unwritten trade and

trail

customs, or merely the will of the strongest

being.

AD&D adventurers tend to run

afoul of

such laws all too frequently, and the DM

who wants to keep PCs

alive (rather than merely having the

blackguards hanged for any offense)

must inevitably make use of some local

system of specific punishments.

Such punishments may include any or

all of the group including confinement,

enforced service or labor, confiscation

of property, and infliction of physical

pain. We shall examine these in detail

soon enough.

Travelers are advised to beware of peculiar

local laws and customs. For example,

“in Ulthar no man may kill a cat.”¹

Local religious beliefs may prohibit the

speaking of certain names or the use or

wearing of sacred (or accursed) symbols,

substances, or colors.

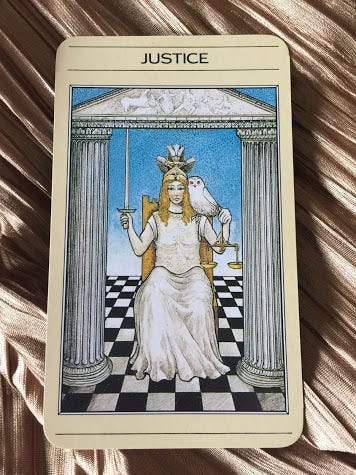

If caught and convicted, miscreants

will find the nature and severity of penalties

varies, depending upon the alignment

of those making judgement and the

existing rules regarding sentencing.

Criminals are often specially marked (by

dress — or lack of it — and/or symbols

branded or painted upon the body), and

an unwitting stranger whose appearance

resembles that of a criminal may be surprised

at the treatment he or she receives.

Some large measure of common (or at

least economic) sense can be expected

in the written or stated laws of any area.

However, a nation that exists by trade

is

not going to have laws that reflect casual

or relentless, consistent hostility toward

foreigners. On the other hand (again logically),

such a nation may well have laws

that prohibit foreigners from acquiring

control or ownership of the all-too-scarce

soil, or any vessels of that country. A

further example of the logic behind most

state or imperial (but not, as we shall

see,

religious) laws involves a look at capital

punishment.

All societies have had the death penalty,

but this is often used only when life is

plentiful. A good man-at-arms, years in

the training, is too valuable to kill except

when he is mutinous or must be made an

example of, for some deliberate disobedience

or other. Slavery was an oftpracticed

alternative — instead of one

meal for the dogs, the captor got the

life’s work of a man, usually at the most

dangerous and undesirable tasks.

Another solution (and one ideal to a

DM wanting to shift play to a new setting)

is banishment — the exile of an

individual by order of a ruler or government.

This involves the outlaw taking an

oath to leave the country within a stated

number of days. (Refusing to take the

oath, before assembled witnesses, usually

means the person refusing banishment

will be put to death.) A banished

person is usually told what route to take

out of the country and where to leave its

borders.

In medieval England, banished persons

might be slain by the superstitious

commoners, and so had to wear a white

gown and carry a cross (signifying that

they were under the protection of the

church). Upon reaching the port of departure,

an exile-to-be had to live on the

seashore until ship passage was available.

During this wait, the outlaw had to

depend on local monks for food and was

required to walk into the sea until completely

immersed, once a day, under the

eyes of the local sheriff.

Outlaws of wealth and influence could

hire a ship to take them and their property

from England, and arrange for future

income to be sent to them. But those

lacking friends and money were usually

put aboard a ship by port officials regardless

of the wishes of the ship’s captain

— and were often thrown overboard

at sea, put ashore on an island or deserted

coastline, or enslaved.

When England was at war, banishment

usually proved unworkable. Most outlaws

were merely compelled to leave the

settlement where the banishment order

was served, and thereafter allowed to

wander free. Most took sanctuary in a

church or abbey (joining a crowd of

thieves and those fallen from political

favor who lived on the monks’ dole in all

such places), or became poachers and

highwaymen in the forests or marshes,

like the man made famous in legend as

Robin Hood.

A change of government, of course,

can put a banished or tied-to-the-sanctuary-

of-a-church character back in favor

— and freedom — again, but in other

situations a church could be more dangerous

than the palace.

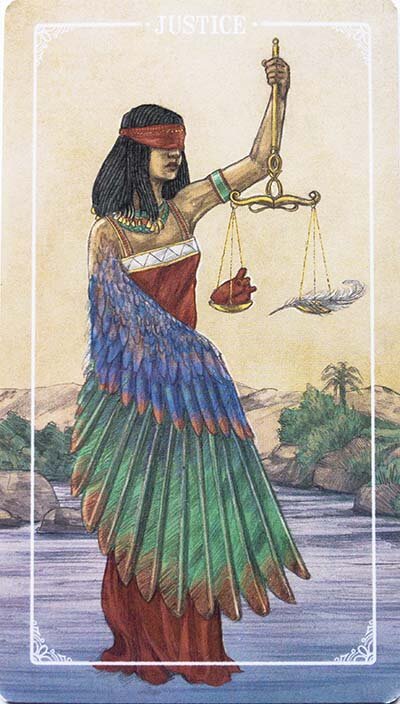

The two most common medieval-era

lawmakers (and enforcers) were the

church and the state. If the latter was

one

man, his justice was as inconsistent and

intemperate as the man himself. If church

and state were one, or if the church had

a

free hand to dispense its justice, laws

tended to be without exception harsh

and unforgiving. Theocracies (refer to

the Theocracy

of the Pale in TSR’s

WORLD OF GREYHAWK™ Fantasy Setting)

are by nature intolerant.

Because religions are based upon belief,

often belief (“faith”) without supporting

facts or “real” conditions, religious

rules and the enforcement of same

tend to be most dangerous. Unfamiliar to

a stranger because of this loose connection

with reality (and at times, common

sense), such rules are inadvertently contravened

often and with ease. Adherents

of the religion are not easily induced

to

show mercy to wrongdoers (and almost

never will they “turn a blind eye” or make

exceptions from holy justice), because

they believe (often blindly) in their religion.

Challenging the religious beliefs of

such people is seen by them as a direct

threat (and the challenger as an agent

of

an opposed religion — “servant of the

devil”) because they have based their lot

on the religion — and to threaten it

threatens the very meaning and worth of

their lives.

At the same time, religious judgements

seldom vary from a traditional code, set

down and modified by high priests and

extant “holy writings.” The universe postulated

assumes a world in which gods of opposing

alignments and interests are locked

in continuing conflict through their

worshippers.

Note further that the distance between

common sense and some religious doctrines

makes guessing as to specific religious

tenets a perilous affair; religions

are often not even self-consistent, let

alone consistent with surrounding “reality.”

Adventurers should be wary of assuming

that followers of a god of the

forest will revere trees, for instance;

in

religions, nothing

“necessarily follows.”

Thus far we have covered two types of

law: that of the government or ruling authority,

and religious law. There is a third

type of unwritten “law” ignored in most

AD&D play, and it may well be

considered

the most important: local customs,

lore, and beliefs.

In our real world, only in the last

hundred years have customs and folklore

ceased to be governing forces in

everyday rural life. In medieval times

they touched upon almost every act in

family and village life, providing the

rituals,

preferred conduct, and rules for utmost

happiness, security, and prosperity.

Dark superstitions and taboos (often

remnants of fallen, forgotten cultures

and religions, divorced from any discernible

meaning or reason for being in

the present) abounded — and these local

customs and taboos were often as

strong, or stronger than the laws of

church and king.²

Outsiders entering a

community were often regarded with

suspicion for the mere fact that they

were outsiders — in more than one fantasy

novel the author carefully points out

that “stranger” and “enemy” are one and

the same word in a local language — and

any transgression of, suggestions contrary

to, or ridiculing of local customs

and taboos they committed won them

the enmity or open hostility of the locals.

To threaten the beliefs of a community,

as to threaten those of a religion, is

to

threaten its very existence — and its

members will act accordingly.³

Until rapid, dependable means of

transportation and communication become

available to all, most dales and

other geographically isolated communities

will be self-contained, largely cut off

from the outer world. The fewer travelers,

the fewer new ideas — and the less

tolerance for differences from local ways

and beliefs. The spread of literacy will

also increase tolerance and weaken unthinking

belief in the old ways, but the

tenacity of superstitions is shown in our

own society by a great array of superstitious

sayings that, half-hidden, remain

today, along with the thinking that goes

with them. This can be illustrated by

such expressions as “There’s no harm in

trying,” which once meant literally that

— according to the beliefs of the speaker

(and the community) — there was nothing

wrong or dangerous about the act in

question.

Many ancient rituals (such as Twelfth

Night fires, placing a cake upon the

horns of “the best ox in the stall” to

be

tossed in the air, and baking a hawthorn

globe each New Year while last year’s

globe was carried burning over the firstsown

wheat) were concerned with the

fertility of the farm. Ploughing and pulling

matches are two of the few such

customs that survive to this day. No matter

what the fantasy setting, where there

is agriculture there are sure to be rituals

for the best time to sow and to harvest

(such as with the phases of the moon, or

in concert with certain weather conditions

or natural changes like the opening

of certain blossoms), and rules to be followed

for avoiding death or ill luck and

for gaining good luck.

The DM, of course, must judge the accuracy

of such beliefs (such as “never

fell a tree by moonlight”) as far as the

party is concerned. Even if the beliefs

are

incorrect, the DM should remember that

they must at least be based on something

real or correct.

Such beliefs are not restricted to farmers.

Blacksmiths held that iron would not

weld when lightning was near, although

they set out troughs and barrels to catch

“storm water,” which they believed particularly

effective for tempering iron.

Countless other examples can be found.4

Note that local lore and the religious

situation will determine what form of government

is tolerated — and if government

is imposed by force, or becomes

unpopular after its establishment, how

well it will be obeyed. Locals may pay

only lip service to some laws and taxes,

or worse (does anyone remember the

Boston Tea Party?).

The support of the ruled (by accepted

custom and belief) lends stability to a

government. This in turn allows weak

rulers to keep their positions, at least

for

a time.

Most countries of any size, wealth and

influence have reached that condition by

the stability of popular (or at least,

accepted)

rule. In any land where communications

and travel are only as fast as a

good horse, the government must be

both strong and accepted by the populace

— or its rule will extend only as far

as the immediate reach of its weapons.

Raw power is, at best, an unstable

form of government (and just as shaky

for a legal system). It has a tendency

to

blow up in the ruler’s face — just ask

Robespierre.

Many types or structures of governments

exist, some of them quite noveI.5

DMs should also remember that the

“king” of Aluphin may command mighty

hosts of warriors and speak with authority

backed by gods, whereas the “king” of

the adjacent realm of Berdusk may be

only a war leader whose rule extends as

far as the swordpoints of his bodyguards.

Bruce Galloway, in his book Fantasy

Wargaming

(Cambridge, Patrick Stephens

Limited, 1981) reminds us that

this variance in real power among nobles

with the same title was true in our real

world, too:

English

kings were relatively

strong, except

during times of royal

minorities

and disputed succession.

They held

wide personal estates,

and maintained

the nucleus

of their own

standing army. A network

of royal officials

exercised

justice and

administration even

within the

lands of their nobles. By

contrast,

the French kings were

weak, little

more than primi inter

pares (“first

among equals”) in

comparison

with strong dukes and

counts. Germany

had what might

be considered

impossible — a

strong monarch,

but also dukes

and margraves

. . . akin to kings

themselves.

. . Italy, with its pattern

of city-states

and rural duchies owing

little or

no allegiance to any

monarch, needs

different treatment

again.

Whatever the actual balance of power

within a country and between different

countries — and remember, this is not

something set in stone by a DM to be

stable and unchanging forever; power

can and should shift constantly — those

who rule will control the citizenry (including

PCs) by means of laws.

Regardless of exactly what laws a DM

creates for his world, they will be broken

by player characters sooner or later (in

the AD&D world, usually sooner),

and

then — it’s punishment time.

The forms and aims of enforcement

are up to the DM, and must be tailored

to

match the other elements of society in

each local situation. For example, given

this imaginary example of law enforcement,

think on what it reveals of the society

of Zeluthin: In that city, political

prisoners are always strapped to their

cell doors, feet off the ground and facing

inwards into the darkness, so that the

backs of their heads are visible through

the barred cell doors. Punishment in Zeluthin

is a delicate art consisting of manipulation

of facial, head and neck muscles

with fingers and long, delicately

curved and fluted metal instruments —

from behind, through the cell door.

Strangulation is never employed; it is

the

height of coarse bad taste; but much information

is extracted by somewhat less

violent extremes — such as when hungry

rats are let in to the darkest corners

of

the cell.

Another city would find Zeluthin’s

habits disgusting or criminal; a DM must

carefully make government laws, local

religions and attitudes consistent.

Some general comments, however,

can be made as to how to handle local

enforcement forces and prisons — and

how not to handle them.

The discipline and training of local

guards/watch/militia/constabulary will

determine their reactions to any situation.

The better the training of the guards,

the more difficult will be the lot of adventurers

seeking to dupe or escape them.

Trained, experienced guards, for example,

will seldom be in awe of magic, and

will know effective tactics for when they

encounter spellcasters in battle. Experienced

guards will leave fewer avenues

for escape when confining persons —

and will take special care of extraordinary

individuals, such as adventurers. A

party may find itself stripped — clothes

can conceal, or even be, weapons — and

then chained securely to walls in separate

cells (in such a manner that movement

of hands and speech may be impossible)

and watched over carefully

(one to one) by guards who are relieved

often. Unknown to player character prisoners,

a magic-user may be spying on

them through use of Clairvoyance, Clairaudience,

ESP and related spells.

Guards with

good training and resources

may have monsters (war dogs, for

example) which are trained to aid them

in fighting intruders/rescuers or inmates

attempting to escape. Too many AD&D

adventures involve a party of player

characters sneaking and ambushing

their way through an unbelievably stupid

and unorganized defensive corps who

make no attempt at internal communication.

Slain or missing sentries go unnoticed,

and guard patrols walk past or

through treasures or areas they are supposed

to be guarding without routinely

examining their charges (so that party

members hiding in shadows, behind altars,

or in dark rooms are undetected).6

The discipline of a guard corps will

also determine its treatment of prisoners:

highly disciplined guards will act

according to rules, and will respect any

legal rights prisoners are considered to

have. Usually, confiscated goods will be

carefully itemized and stored (for return

when or if the prisoners are set free),

punishment of prisoners confined to a

special code, and prisoners will (at least)

be given food, water, and conditions of

confinement conducive to survival.7

Guards lacking such discipline may

do anything to prisoners they think they

can get away with — and in the case of

outlanders without apparent rank or influence,

this can include various means

of death-dealing, selling into slavery,

and all manner of theft.

Good characters (and players) who

are shocked at this tendency would do

well to remember that the essential difference

between a policeman and a pirate

is how they regard themselves, and

how they are regarded by the populace,

in relation to “rightful” authority (local

government). The actions of the two

types are often very similar.

Mention of the attitude and regard of

the populace brings us to the backbone

of local life and character; the evermoving

and changing, vital force behind

the laws, customs, and other elements:

politics. In the article “Plan

Before You

Play” (DRAGON™

issue #63), we looked

at politics on a large scale: the trade

links, tensions and history that shape

empires and denote wasteland and impoverished

areas, viewed broadly upon a

map.

But more important in AD&D play

is

the to-and-fro of local human interaction,

the politics of everyday life in a village

or a kingdom. A DRAGON reader

can refer to the previous Minarian

Legends

series or the currently running

World

of Greyhawk columns for excellent

examples of the large-scale politics

<(by Gary Gygax:

Dragon

#64)>

<(by Robert Kuntz:

Dragon

#63, Dragon #65)>

of fantasy worlds, but small-scale politics

(beyond Chaosium’s Thieves’

World,

which deals with the desert city Sanctuary)

is something each DM must devise

on his or her own.

Development of local politics will give

any campaign depth and believability,

and at the same time create reasons and

impetus for characters to undertake adventures

(and players to role-play). Make

a world seem real, so that what occurs

matters to the players, and you will make

play far more enjoyable and memorable

— and a DM owes it to his or her players

to give them an active, living world to

engage their interest, rather than a colorful

background of artificial, lifeless immobility

through which characters are

allowed to rampage.

This latter condition in a campaign

dooms play to eventual boredom, until

the playing activity ceases altogether.

If

the setting has no interest for the players,

no apparent life of its own, it must be

continually fed with the energy and excitement

of new characters and character

classes, new treasures, new monsters

and magic and traps . . . and when the

players grow jaded or the DM runs out of

ideas, the whole campaign runs down.

Even the gaudiest trappings cannot sustain

interest; one grows used to throne

rooms if one is a fighter in the party

that

conquers one kingdom after another,

just as one grows used to dark caverns

and locked chambers underground if

one lives like a mole, in an endless dungeon

with nothing to do but fight.

If a DM does not have the time or liking

for careful crafting of local politics,

history,

a cast of characters, and the like, a

simple solution is to sketch out the basic

history and geography of a region, and

begin play within its borders, in the midst

of a civil war.

The disorder, lawlessness, and intrigue

such a setting offers will get a party

off to

a good (exciting and offering wide experience

in fighting) start. Players should

be forced to take sides and become involved;

fantasy readers may recall the

excitement of Roger Zelazny’s 5-volume

Amber

series, which was primarily a

family struggle for control of a multiverse.

From such a rocky start, play can

shift into more conventional AD&D

territory,

perhaps with involvement in the intrigue

and politics of a large city with

warring guilds and the like and eventually,

when the successful, experienced

players seem ready for it, player characters

may have a crack at gaining control

of their own territory.

This territory should be small, so that

a

DM can concentrate on individual NPCs

to make the place seem real, and so

players can identify with their holding

— seeing it as a specific region with its

own character and beauty — and at the

same time seek to expand it. The DM

should also ensure that the players act

to

keep their lands, becoming involved in

trade and diplomacy as well as battle.

The notion that lands are a rosy source

of revenue, which novice players may

get from the Players Handbook (i.e.,

a

9th level

fighter who establishes a freehold

can automatically and effortlessly

collect 7 silver pieces per month from

“each and every inhabitant of the freehold

due to trade, tariffs, and taxes”),

must be quickly dispelled. Governing is

work, and a DM should see that those

who enjoy such work are happy in

their

thrones, and those who are not cannot

safely delegate the tasks of ruling to

others

if they wish to retain power for long.

Few medieval rulers were rich, in cash

terms, and fewer still spent most of the

taxes they collected on living high; rather,

most of a ruler’s money was needed

to cover military expenses (the training,

outfitting, boarding, and salaries of any

standing army, plus militia and/or mercenaries),

and the repair, expansion and

addition of ships, buildings, and fortifications.

Trade and the support of innovations

in industry and medicine are

other areas of expenditure a ruler should

keep in mind.

Even if a lord finds his subjects happy,

no priesthoods or guilds opposed to his

rule and no apparent problems, he can

always find something like this affixed

to

his castle door one morning:

To Doust Sulwood,

resident in

Shadowdale:

Recently I

have learned that you

have taken

the title, authority,

and lands

that are rightfully mine.

Shadowdale

has been my family’s

since the

death of the lord Joadath,

sixty winters

ago. I shall come for

my throne

ere spring. If you think

your claim

stronger than mine,

send word

back — or I shall come

with force

of arms to take back

what is mine.

Lord Lyran

of the family

Nanther,

Melvaunt

This sample letter is from my campaign;

the players do not (yet) know

whether “Lord Lyran” is a pretender or

a

legitimate claimant to the lordship of

Shadowdale (local history is incomplete

and contradictory on the subject). A

quick look at Doust Sulwood, the Lord of

Shadowdale (a PC), and

his plateful of problems will demonstrate

the depth, excitement, and constant adventures

generated in a campaign by local

society and politics.

Doust Sulwood is lord of a farming

community surrounded and largely isolated

by elven-inhabited woods. It is a

stop on a major overland trade road, and

has successful, if unspectacular, local

industry (a weaver, a smith, a wagonmaker/

woodworker, and of course an

inn). Doust has a few local problems:

collecting taxes (the dalefolk had been

without a lord or taxes for some years

before his arrival), settling local feuds

and ferreting out a lycanthrope among

the townsfolk, and dealing with incumbent

power groups: a band of adventurers

(all more powerful than the players,

and used to being the local champions

and heroes); the Circle (a group of druids

and rangers who work with the elves to

preserve the forest against fire and farm

expansion); and a few powerful solitary

NPCs who could topple his lordship if

they decided against him. All of these

power groups have their own interests,

and all of the them have more personal

power than the Lord and his party. Both

the elves and the druids have (PC) representatives/spies

in the

party.

From outside the dale there are influences

too. Many nearby rulers and priesthoods

have, or are about to, send envoys

to Lord Doust, seeking (nay, demanding

and often bribing or threatening) alliances,

allowances of free trade and the

powers to establish temples and tithe the

populace. At least two dale lords are eyeing

Shadowdale as a possible addition to

their own lands — and the player characters

have made special enemies of a secretive

network of evil mages and clerics

who wish to control all overland trade

between the rich coastal cities and the

lands about the Inland Sea. Shadowdale

occupies a strategic location on the caravan

route, and the party has — at first

unwittingly, and then in careful selfdefense

— slain many members of this

evil “network.” Party members have also

died in the running battle, and with the

spring thaws their surviving comrades

may face a network-sponsored army invading

the dale. At the same time, the

drow — now apparently allied with some

githyanki — seem to be stirring in the

depths. Lord Doust’s tower was built by

the drow, and it once guarded the entrances

to their vast subterranean realms.

The dark elves were driven into the

depths over a hundred winters ago, and

the exits were blocked. Now they seem

to be returning, and have kidnapped one

of the dalefolk (which the party subsequently

rescued) to learn details of society

and property in the dale.

To Doust’s ears also comes a constant

flow of news about current events, coming

to Shadowdale via caravan, and the

party can learn much of movements and

political actions by careful attention

to

and interpretation of the “current news

daleside.”

All of the aforementioned conflicts

and challenges come to the party, made

up of characters with personal problems

and interests of their own. In Lord Doust’s

case, he is a cleric of Tyche, the goddess

of luck, who wants her followers to lead

daring, chancy lives. This was an easy

creed to follow when Doust was a landless

adventurer; but now, when he wishes

to build his strength and act with caution

and deliberation in the face of all these

dangers and demands, he finds himself

torn between Tyche’s dictates (which he

must follow if he expects the goddess to

grant him spells, and if he wishes to rise

in her service; that is, gain levels) and

his

own enjoyment of adventure, and the

necessary prudence of a ruler in such a

delicate and dangerous situation.

Such playing conditions make for excitement

and good role-playing. Players

are interested in the campaign because

every adventure becomes (through cause

and effect) important, not just in terms

of

treasure and experience gained, but in

terms of social consequences. Moreover,

with such a lot going on, the interaction

of players and NPCs generates adventures;

there is always something

meaningful to do. This sense of purpose

serves to sustain interest over lengthy

campaign play, makes the fantasy setting

seem more real, and makes successful

play more satisfying: Players gain a

real sense of accomplishment when they

complete sticky diplomatic negotiations,

gain allies, find a path through intrigue,

or destroy long-standing foes. And in

this increased enjoyment of play lies the

real value of such an approach to the

AD&D game.

It may seem odd to increase the enjoyment

of fantasy role-playing by increasing

the problems and difficulties of

the setting (so that it seems you’re not

many DMs use a world in play — and

such overmanipulation quickly sours

players who feel that, rather than playing

the roles of adventurers, they are portraying

helpless pawns at the mercy of a

vindictive god. DMs who believe that this

is precisely how players should feel will

probably have stopped reading this article

long ago. DMs who find enjoyment in

creating a fantasy world they can share

and delight in with other people will,

I

hope, find what has been said here

useful.

________________________________

. . . the escalation of

treasure, monsters and

character experience

will ruin a campaign . .

.

a world requires careful

attention to NPC

activity, so that player

characters are not the

only source of action in

an otherwise lifeless

backdrop.

__________________________________

1 — H.P.

Lovecraft,

The Dream-Quest

of Unknown Kadath,

published in paperback

by Ballantine, 1970 (and recently

reprinted), p. 8. A similar law is in effect

in Rome today.

2 — The strength of such

beliefs as a

code of behavior is illustrated by a Latin

phrase known in modern legal practice:

Multa non vetat lex, quae tamen

tacite

damnavit,

which translates to “Some

things are not forbidden that are nonetheless

silently condemned.”

3 — In his excellent study

of fantasy,

Imaginary Worlds

(Ballantine, 1973), Lin

Carter reports one of master fantasy writer

Lord Dunsany’s touches of realism:

the human nature displayed by the archers

of Tor, who shoot arrows of ivory

at strangers, lest any foreigner should

come to change their laws — which are

bad laws, but not to be altered by mere

foreigners. Another chapter in Imaginary

Worlds,

entitled “On World-Making,” is

essential reading for DMs who have not

extensively explored fantasy literature.

Carter discusses the “sound” and suitability

of fantastic names, as well as providing

a fast, logical geography lesson.

4 — On the shelves of most

libraries

one can find books dealing with local

customs and tradition. One example is

Folklore and Customs of Rural

England

(by Margaret Baker; London, David &

Charles [Holdings] Limited, 1974), which

is chock full of readily usable local lore

— but there are many similar sources.

5 — For types

of government, refer to

the DMG and D&D® module

X-1,

The

Isle of Dread,

and to L. Sprague de

Camp’s The

Goblin Tower (New York,

Pyramid Books, 1968) and its sequel,

The Clocks

of Iraz.

6 — Movie buffs may recall

the scenes

in Monty Python’s Life

of Brian in which

at least a dozen Roman guards repeatedly

search a small set of apartments without

detecting the Judean resistance

fighters, who stand behind tapestries,

crawl under the tables, and dive into

wicker baskets in attempts to hide — and

of course remain in full view all the time.

7 — These will include light,

ventilation,

sanitary facilities, the dignity of prison

clothing or the right to retain one’s

own clothing, acceptable or even comfortable

temperatures, and a relatively

quiet, odor-free environment.