| Ecology of the Umber Hulk | Mines && Metallurgy | Underdark Encounter Tables | The Duergar | Quests |

| Dragon | - | - | - | - |

Duergar (Gray Dwarf)

Dungeon Quest (Games Workshop)

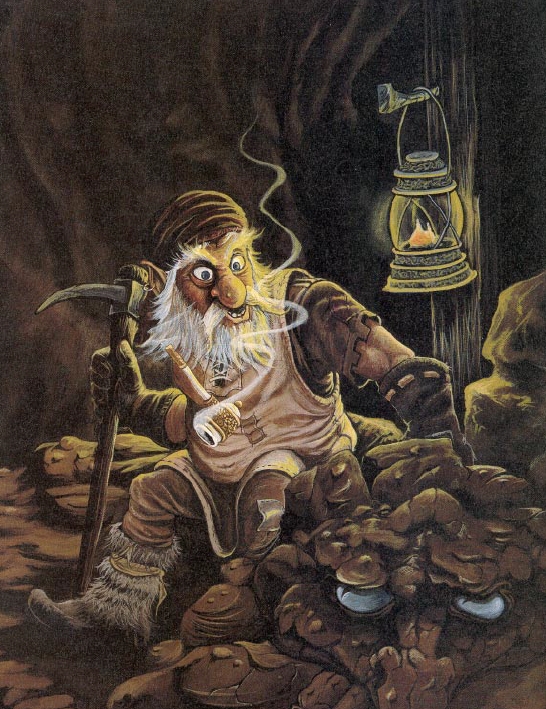

Swap this with the DSG image for mining.

Endless Quest

In a Cavern,

In a Canyon...

Mines

and metallurgy in fantasy campaigns

by Thomas M. Kane

illustration by Jeff Echevarria

| To find a mine | Assaying | Mines and the law | Wheels, gears, and pulleys | Perils underground |

| Digging | Smelting | Ending a mine | Bibliography | - |

"Certainly, though it is but one . . .

method of acquiring wealth . . . a careful

and diligent man can attain this result in

no easier way than by mining." - Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica

Every dwarf knows how important

mines are. As Agricola stated, there are

few better ways for someone to get rich

than discovering ore and digging it up.

Mines also make ideal "dungeons." Adventurers

can comb through abandoned tunnels

or active shafts owned by their

enemies or creatures from below.

The AD&D® DSG

presented some basic information about mining

on pages 48-55.

This article expands that material with information about medieval

prospecting and metallurgy,

based on Georgius Agricola's De Re Metallica, a German text

written in A.D. 1550.

Dwarves, gnomes,

drow,

and humans with the miner secondary skill

or mining proficiency should have access to this knowledge in AD&D

games.

To find a mine

In medieval times, prospectors began

their search for valuable ores in early

spring. They looked for far more than telltale

ore-bearing rocks. Agricola stated that

a warm and dry "exhalation" comes from

underground metal, preventing hoar-frost

from forming on short new grass. By

observing the patterns of frost on grassy

ground, one can see where ore veins run.

Furthermore, trees absorb metal through

their roots, and such metal causes the first

leaves of the season to blacken or fall off if

the trees stand over a vein.

Medieval prospectors knew to look for

natural springs because water often congeals

in mineral veins and flows along

them. This gives the water a distinctive

taste. Salty springs (found inland) indicate

underground salt, and salt would be precious

in any medieval-style fantasy society.

In our own world, a few ounces of salt

were worth more than two slaves as recently

as the 1700s. An experienced miner

could also taste for soda (nitrium), alum,

vitriol, sulfur, and bitumen, all of which

were used in smelting ore, in alchemy, and

in medicine. In the AD&D® game,

bitumen,

sulfur, and alum are also used as

material spell components.

The DM can role-play this search, making

a map of the area of interest and letting

PCs explore it (dwarves might

appreciate this activity most). It takes one

week for a miner to prospect four square

miles, longer if the ore is particularly

difficult to find. As noted beforehand, the

searchers must examine springs and herbs

as well as stones. A group containing

characters with knowledge of mining as

well as wilderness-wise rangers, elves,

druids, and NPC treants (or trees contacted

through speak with plants spells)

can finish the search in half the normal

time. Of course, these latter experts may

refuse to despoil the earth by mining.

Clever NPCs (or PCs!) might guide prospectors

away from veins, to avoid having

forests cut down for timber used in building

the mine itself.

After this exploration, PCs may attempt

mining proficiency checks (explained on

pages 25-26 and 48-49

of the DSG, and on

pages 54 and 61 of the AD&D 2nd Edition

Player’s Handbook). If the checks succeed,

the DM tells PCs where they find springs,

colored trees, or bits of ore (and what

these may mean). Of course, the PCs might

discover monsters or claim jumpers, too,

as the DM wishes.

Miners in medieval times practiced a

whole branch of sorcery. They believed

that ore radiated an aura or ?field?; when

a magician walked over such a field with a

forked divining rod, this field caused the

stick to twist in his hands. Some diviners

employed hazel rods, while others claimed

that hazel could find only silver. The latter

used ash rods for copper, pitch pine rods

for lead or tin, and iron wires for gold.

Others preferred to use magic rings for

divining, and others looked for an ore?s

field by observing the area in a magical

mirror or through an enchanted crystal.

Agricola did not believe in diviners, although

he suggested that such magic

might have existed in ages past. In AD&D

games, a ring of x-ray vision,

might help

prospectors find dense metal ore, and a

wand of metal

and mineral detection could

locate veins (see the AD&D 2nd Edition

Dungeon Master’s Guide, pages 151 and

157, respectively, for more information).

Mages can research spells or develop

items to find ore, using the items described

above as guidelines. Of course, all

magic flirts with peril. New spells might

invoke the elemental plane of Earth,

and

powerful but miscast spells could unleash

volcanoes, earthquakes, or malign beings

from other planes.

Despite their lore, prospectors depend

on luck. Some mines begin in farmers?

fields when plows turn up metallic stones.

Other veins are found after landslides or

earthquakes, and once a wildfire melted

ore near the grounds surface, causing

rivulets of gold to trickle down a mountainside.

The DSG contains guidelines for

placing ore veins, but ore can appear

wherever the DM wants it. Furthermore,

if mining would slow the campaign, no

amount of successful dice-rolling should

produce a vein. Charlatans, ?fool?s gold?

(iron pyrite), and the simple absence of

metal can frustrate the wisest prospectors.

Humans did not practice scientific geology

until the 19th century. However, in a

fantasy world, different races may be

intimately familiar with the patterns of ore

placement underground. Drow and

svirfneblin, among others, certainly know

where the earth hides its metals. Prospectors

might venture underground to beg

the advice of such races, but might eventually

fight these races bitterly. Surface and

underworld miners often clash because

each group desires the same resources.

PCs digging down into ore beds might

meet beings chipping their way up.

Deep-dwelling races know that the earth

is formed in layers of stone and dirt, with

new layers forming over the old. Veins of

ore usually appear where something disrupts

these layers, concentrating minerals

in one place. For example, magma can

squeeze its way into other stones, carrying

ore with it. It forms vertical dikes, horizontal

sills, blisterlike laccoliths, and vast,

rippling batholiths. Diamonds collect in

kimberlite pipes, cones of volcanic rocks

that project upward. Tectonic plates also

alter the geology of an area. A rising plate

might lift metals or oil, creating a chain of

deposits along the edge of a continent.

Underground peoples might also know

about oil. Petroleum collects where the

layers of earth curve, forming a trough or

a trap for it. Petroleum is likely the "flaming

oil" adventurers hurl at monsters; the

only oils in the Middle Ages came from

animal or vegetable fat and were unsuitable

as weapons. Perhaps fantasy warriors

import their oil from the underworld.

Dungeon explorers may grow rich trading

in oil they recover. Petroleum deposits

might also interest Oriental characters; the

ancient Chinese drilled for oil and salt

water with bamboo derricks. Some Chinese

emperors tried to tax these wells, but

rural landlords resisted by posting scouts

who dismantled the drills before inspectors

arrived.

Assaying

Once prospectors discover a vein, they

must evaluate it by assaying (testing) the

ore. Miners often judged unknown ores by

chewing them. They also suspended earth

in water so it could be studied with color-changing

slips of paper, like the litmus

paper used by modern chemists. Roman

craftsmen made this paper by dipping

parchment in shoe-black. It turned green

when exposed to vitriol, a sulfate often

found with metallic ores.

When these tests seem promising, assayers

then heated ore in crucibles. Pure

metals melt smoothly and at precise temperatures.

Medieval assayers used flammable

compounds to measure the melting

points of ores. The craftsmen knew the

temperature at which the powdered compounds

would, combust, so if a molten

metal ignited them, that showed how hot

the metal was. These tests also helped

miners choose fluxes for smelting. Fluxes

are substances that aid the separation of

slag from pure metal in the smelting process.

Different colors of smoke created

during these tests suggested different

chemicals for use as fluxes, and deep

purple smoke meant that the ore needed

no flux at all. Each such test had to be

performed in a cupel, or dish of ashes.

The ashes were especially pure so they did

not absorb the metal. Assayers preferred

ash burned from beech or other trees that

grow slowly.

Experts on metallurgy did more than

test mines. They hunted counterfeiters

and set values for metals. Grossly adulterated

gold (used in forged coins or as part

of a fake gold-mine scam) turns black in a

candle flame. More sophisticated counterfeit

metals appear real but will not melt

until treated with lead flux. Once an assayer

determined that a metal was genuine,

he tested it with a touchstone to

reveal its purity. The sample was beaten

into a needle shape and scratched against

black slate until it left a streak. By looking

at the mark, a learned metallurgist could

determine the ratio of metals in any alloy.

A character must make a smelter profi-

ciency check to assay a sample (see the

DSG, pages 25-26). The tools required for

assaying cost 50 gp, more if pure ashes are

unavailable. DMs should make this check

in secret. If the character succeeds, he

learns the exact purity of the ore or coin

being tested. The DM can determine a

mine's value with the results on Table

33: Ore Quality, on page 51 of the DSG.

If the check fails, the assayer believes that the

mine is either far more or far less valuable

than it really is (there is a 50% chance of

either result). PCs might then abandon a

priceless mine or be convinced that a mine

should be producing more than it does

(and thus conclude that their workers are

stealing ore).

Mines and the law

It appears to be a basic law of mining

that once someone finds metal, the government

will certainly interfere. In Agricola's Germany,

each miner was required to register his mine with the local burgomaster

or town mayor, so he could divide the

ground above the mine into meers. Whoever

possessed a meer owned all ore

found beneath it. Meers were of different

sizes, and the mine's discoverer always

received the largest one. Smaller portions

belonged to business partners and landowners.

The law reserved other meers for

the king, his consort, his master of horses,

his cupbearer, his groom of the chamber,

the bishop, and the burgomaster himself.

The local baron did not automatically

receive a meer. Miners were legally vassals

of the crown and paid tribute directly to

the king.

Metal brings wealth, technology, and

independence in war, so most rulers want

their people to mine. Some kings granted

prospectors permission to dig wherever

they found ore, no matter who owned the

land above it. Other kings allowed miners

to seize only "wastrel land" that was not

being farmed. These laws usually included

another provision requiring miners to

work their mines. If a mine owner failed

to produce ore for nine weeks, the baron

often confiscated his holding and awarded

it to the informer.

Medieval laws also covered labor in the

mines. Shifts could not exceed seven

hours, and foremen had to warn workers

when their time ended. Bosses communicated

with subordinates in deep tunnels

by ringing a great bell called a campana,

by stamping rhythmically on mine timbers,

or by relaying codes of hammer taps

from miner to miner. If miners missed

these messages, their shifts were still

legally over when their lamps burned out.

For this reason, foremen filled the miners?

lamps and weighed them to be sure that

nobody had too little. Most burgomasters

refused to allow foremen to work their

miners at night or for two shifts in a row,

except during emergencies. The miners

usually resented these rules, since they

wanted two shifts? worth of pay. (As a side

note, many miners fell asleep in lonely

tunnels even during a single shift. Miners

sang to stay awake, and Agricola noted

that the singing "is not wholly untrained

or unpleasing." Dwarves, gnomes, humans,

and other races that are not accustomed

to eternal existence underground might do

the same; the dwarves in J. R. R. Tolkien's

The Hobbit sang--and quite well, too.)

Wheels, gears, & pulleys

Ingenious machinery filled medieval

mines. Agricola considered the idea of

carrying ore out on workers? backs barbaric

because mine carts had replaced

porters for centuries. Carts were rolled

into a mine on tracks using the force of

gravity, then pulled out by mules or pack

dogs. (In AD&D game terms, pack dogs

are treated as war dogs and carry 20 lbs.

at normal speed or 50 lbs. at half speed.) <check the article on

dogs:

Draft dogs / sled dogs are either Medium

normal dogs or Large normal dogs>

Outside the mine, daredevil sledge drivers

guided loads of ore down mountainsides,

steering themselves with poles. Agricola

mentioned that these sledders worked

?not without risk of life.? Other loads were

lifted out of vertical mine shafts by cables.

Hand-powered windlasses and cranes

operated by treadmills dotted the ground

above mines. Miners did not even have to

climb down the shafts to work. They slid

on chutes or clung to rope elevators powered

by treadmills.

Some mines flooded constantly, so organlike

pump arrays descended into the

tunnels, powered by treadmills or water

wheels in nearby streams. Some pumps

used a single plunger, while others involved

dragging a chain with bundles of

watertight leather set at given intervals

through a pipe. Pumps become inefficient

when the distance they travel is too long,

so deep mines used other systems. Some

dragged chains with buckets attached

through the water. Others required pump

relays, each one raising water one level

using buckets or Archimedes? screws.

Relayed pumps could use relayed water

wheels, in which water poured down a

deep shaft and turned a different engine

on each floor.

Nothing could be more important than

oxygen to miners of any race. Medieval

engineers dug horizontal shafts into mountainsides

so air could flow freely into some

mines, but many lodes were too deep to be

reached in that manner. In windy spots,

miners used funnels and pipes on the

surface to ventilate tunnels. These devices

had fans that rotated in the wind using

vanes and sails. Deeper tunnels required

miners to invent various air pumps, including

men fanning air into shafts with

linen sheets, feathered propellers, vast

blower boxes powered by water wheels,

and gigantic bellows. Gearboxes allowed

these air pumps to be powered by treadmills

or water wheels as well as by hand.

When these devices break (or are sabotaged)

in game campaigns, characters

might be trapped without fresh air. A 10'

cube (not '10 cubic feet' as noted in the

DSG, page 36) contains

enough oxygen to <i have corrected the text in the DSG - Pres>

last one man for one day. If the character

exerts himself by exploring, fighting, or

digging, he needs twice as much oxygen.

Fires also consume oxygen. A torch

consumes a 10' cube of oxygen in eight

hours, and a small bonfire uses this much

in two hours. Burning oil uses 10 times as

much oxygen as a wood fire, so an oilburning

fire uses up a 10? cube's oxygen in

only 12 rounds. An adventurer can hold

his breath for a number of rounds equal

to one-third his constitution, rounded up.

After this, the character must attempt a

1d20 roll against his constitution each

round, with a penalty of +2 per round.

When this roll fails, the victim suffocates.

More information on this topic is contained

in the DSG, pages 36-38.

Perils underground

Medieval miners believed that a whole

host of demons and gnomes lived in the

shafts with them. Most tunnel spirits were

benign. They appeared to work vigorously

and carry away ore, but they never

seemed to deplete the veins. These creatures

threw pebbles at workmen who

teased them but did no harm. Other

haunts were invisible but made knocking

noises. A few demanded offerings before

they allowed anyone to dig their favorite

lodes. Anyone who refused to give an

offering would die by falling down a shaft,

being buried by a cave-in, or becoming a

victim of one of the mishaps so common

underground. The same spirits befriended

kindly people and led them to riches.

In AD&D games, these creatures would

be

pech, booka, and underground pixies.

Miners dreaded the more fearsome

creatures. They considered it impossible

to keep kobolds out of mines, and these

small evil beings supposedly sabotaged

elevators, allowing people to plunge into

the depths. (Miners also believed that

cobalt, a gray metal later used in alloys

and paints, was a worthless metal substituted

for silver by kobolds in the mines.)

Deadly ants and solifuga (sun spiders,

tiny

versions of those in Monster Manual II)

stung people who sat on them. Many

believed that each mine had its own breed

of poisonous bugs; nothing could save

their victims except a drink from one

particular hot spring that was hidden

somewhere within the same mine (which

DMs may wish to include).

The earth that miners dig can kill them,

too--and it does so in real life. Ordinary

dust scars the windpipe and causes lung

diseases in old age. Other powders corrode

the lungs at once, and Agricola reported

that in the Carpathian mountains

most women married at least seven husbands,

as one by one each man smothered

underground. A black dirt called pompholyx

settled in open wounds and ate them

to the bone. It also destroyed iron, so

wooden tools were used in the mines it

infested. Cadmia dust does even more

harm; it can burn into uninjured skin

when moistened. A greenish metal called

kobelt was said to devour the feet of men

who walked over it. This was the origin of

the word 'kobold,' because people assumed

that little goblins laid kobelt traps

on purpose. Miners protected themselves

from these dusts with sealed leather coveralls

and breathing masks made of animal

bladders.

Poisonous dusts like pompholyx do no

harm to healthy characters, but they

infect any wound that is not bound within

one round after contact. Pompholyx

causes 1 hp damage per round to such

open wounds until half again as much

damage is taken as the character originally

suffered. Any iron exposed to pompholyx

(including armor) must save vs. acid every

hour or be damaged. Armor loses one

armor class of protection; weapons suffer

a -1 on damage rolls, and small items

break. Intelligent enchanted swords plead

not to be exposed to pompholyx. Cadmia

dust causes 1-4 hp damage per round, or

1-8 hp damage if the victim has wet skin.

Kobelt destroys boots after 1-10 turns (if

not brushed off) and causes 1 hp damage

per round to bare feet. When characters

stand on kobelt without shoes, they must

save vs. poison or be unable to stand

thereafter until their wounds are healed,

otherwise falling to the ground in the

kobelt for 1-10 hp damage. (Kobelt might

also be green slime.) Protective clothing

prevents damage from dusts, but such

clothing is useless once perforated. Whenever

a PC suffers damage, he must make a

dexterity check on 1d20 to protect his suit.

People who get any corrosive dust in

their eyes (for whatever reason) must save

vs. poison or go blind. Dusts have a 20%

chance of blinding both of a person?s eyes

even if only one eye is exposed, due to

sympathetic eye syndrome.

Stagnant air in mines could be cleared

with pumps, but poisonous gases killed

victims nonetheless. Dangerous fumes

arose from some ores but could usually be

detected with candles (which burned in

different colors) or with canaries (which

died when exposed to methane, as per the

DSG, page 37; checking for

methane with

open flame is dangerous, as it will cause

an explosion). The most common poisonous

gas was carbon monoxide, created

when workmen set underground bonfires.

These fires were necessary to heat rock so

that it could be cracked open with cold

water. Miners usually did this chore on

Friday, evacuated their tunnels, and did

not return until Monday. Some smoke

settled on water, forming an arsenic film

that floated into the air when the pools

were disturbed. Those who survived the

fumes reported that their limbs swelled

until their hands and feet were spherical.

Agricola reported watching men climb

ladders to escape arsenic gas, only to fall

as their fingers grew too bloated to grip

the rungs.

Sulfurous fumes, present with volcanic

activity, suffocate victims as if there were

no oxygen in the air (see the DSG, page

36).

Carbon monoxide smothers any character

in only 1-3 rounds because of its

potent poisons: Anyone exposed to arsenic

gases must save vs. poison; if the roll fails,

he is immobilized by swelling. Arsenic also

smothers victims as if it were carbon

monoxide. When this material settles in

pools, characters can walk past safely.

However, when anything disturbs the

water, gas is released. If a character actually

touches the water, he must save at -3

or be paralyzed and begin to choke. Furthermore,

anything wetted with arsenictainted

water exudes poisonous gas in a

10' radius until it is scrubbed.

Some PCs may want to use these

chemicals

against enemies. If so, the DM should

remember the dangers of carrying these

poisons and being caught in one?s own gas.

None of the gases but arsenic have any

effect aboveground in open air. Even inside

buildings, they disperse too quickly to

kill most people, given an open window or

two. The corrosive dusts cannot cause full

damage except when concentrated. A few

handfuls of kobelt or cadmia should be

treated like the acid described in the

1st

Edition DMG on page 64. Pompholyx cannot

harm living things aboveground. PCs

might use it to sabotage iron objects, but it

would have to be applied directly and

allowed to sit undisturbed for one hour.

Mines can also collapse. Tunnels in

AD&D campaigns must be supported by

timbers or stone every 10?, and these

supports require four man-hours to construct,

given a source of wood or worked

stone along with ways of transporting it to

the mine. With supports, there is a 2% per

day chance of a cave-in somewhere within

the mine; without them, there is a 10%

chance per turn that a once-reinforced

tunnel collapses. The DM should decide

where the cave-in occurs, placing

it wherever

miners have weakened the ceiling

most recently (also see the tables on pages 39-40 of the DSG).

Damage from falling rock

is given in the DSG on page 40.

Even

if cave-ins miss characters entirely, they

may trap the PCs underground.

Table 27: Mining Rates, on page 50 of the

DSG,

shows how fast rescuers can dig. Victims

may try to scoop their way out, but unless

they have picks and shovels, they dig at

one-quarter the usual rate.

Digging

Determine a mine's output by calculating

the amount of ore its workers can dig

each day, using Table 27: Mining Rates,

on

page 50 of the DSG. Some magic, including

dig and move earth spells and spades of

colossal excavation, may speed the work.

The tables in this article show how difficult

ore is to dig, what it weighs, and how

much metal can be extracted from it.

Tables on pages 50-52 of the DSG help the

DM determine other details, such as the

location of veins and their composition.

<These tables are : Table 30: Mining

Products, Table 31: Mithril Check,

Table 32: Gemstones, Table 33: Ore

Quality, Table 34: Gemstone Quality.>

Remember that ore not only needs to be

dug, it must be transported to a smelter.

Table 1 herein describes common sorts

of ore and the ease of mining them. The

classification of an ore as 'hard or ?soft?

applies to the Mining Rates table previously

noted. Weights are given in pounds

per cubic foot.

Ore appears in vertical columns called

vena profunda, horizontal veins called

vena dilatata, or lone masses called vena

cumulata. Use Table 28 and Table

29 on page 50 <alt>

of the DSG to determine where the vena

dilatata go or else choose the direction.

Vena cumulata and vena profunda can be

approached from above and are easy to

excavate using vertical shafts. Miners dig

vena dilatata while lying down; this keeps

miners from wasting time digging useless

stone but forces them to work in cramped

positions, Dwarves excel at this job because

they fit into. these narrow tunnels.

Larger miners can only mine these passages

at 75% their normal rate, or one-half

the normal rate if they insist on digging

tunnels n which they can stand upright.

When characters smelt their ore, you

will need to know how much metal the

ore contains. Table 2 herein converts the

Ore Quality table on page 51 of the DSG to

the gold-piece weight of actual metal per

25 cubic feet of ore, the typical daily production

for a human miner in hard rock

(this is about the size of a 3? cube). When a

mineral can be extracted from different

sorts of ore, a letter code indicates wha

sort of ore is present.

No one mined platinum until the 18th

century. It was first found in riverbeds as

part of a native alloy. This metal had to be

dissolved in aqua regia and reprecipitated

to form platinum. The exact methods used

remain trade secrets even today.

Smelting

Once the ore is aboveground, it is sent

though a new series of machines. Workers

sort ore from stones by hand because

plain earth soaks up metal when the two

are placed in a furnace together. Each

metal requires different treatment. Antimony

had to be treated gingerly, because

alchemists warned that it might turn into

lead. Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist,

recommended mixing silver and gold ores,

claiming that the electrum produced

would create magical lightning and detect

poison by turning black. When gold or

silver mingles with lesser ores, acid is used

to dissolve the unwanted metal. Adept

miners could then reconstitute the other

metals from solution. Some miners were

even brave enough to dissolve the gold

with a mix of hydrochloric and nitric

acids, then precipitate it (check a basic

chemistry text for details).

Gold can usually be washed out of its

ore without heat or acid. There were an

amazing variety of machines for purifying

it, all based on the principle that gold is

heavier than dirt and settles to the bottom

when suspended in water. ?Panning? by

hand is the most basic version of this

method. Other systems involved placing

the ore on a screen with a tray underneath

and running water over it, or lining

streambeds with collector plates. Workmen

patrolled these chutes with hoes to

push lumps of gold back into the plates if

they were washing away.

Ore that is to be smelted in a furnace

must first be crushed. Some mine owners

employed men with hammers to beat the

stones, but mines with nearby streams

used water wheels to power huge automatic

hammers or grindstones to grind

soft ore like wheat. (Orcs or other foul

creatures might enjoy pounding people in

this machinery.) Smelters roasted ore in

open fires to burn away sulfur and bitumen

before placing it in the furnace. In

the smelter, ore was mixed with appropriate

fluxes to make metals melt easily and

at regular temperatures. Copper will not

melt until all traces of iron with it have

melted, so it is never worked with iron

tools. Most furnaces required large bellows

or mechanical blowers, and some

were so large that operators needed

cranes to open them. However, even these

furnaces were not always large enough. A

few miners preferred to build hills of ore

against windy mountainsides and smelt

hundreds of tons at once. Other smelters

completely automated the process of refining

metal, using water-powered conveyor

belts and engines to crush, rinse, strain,

and heat the ore.

It is always worthwhile to recycle processed

ore. Some smelters accepted their

slag instead of a fee, knowing that the slag

still contained valuable metal. In the case

of gold, even the water that washed it

remained precious. Many miners strained

gold dust from waste water with sheep’s

wool, and Agricola suggested that this was

the origin of the Greek myth concerning

the Golden Fleece. Clever miners could

always extract even more gold by mixing

mercury with the ore. Smelters put the

most promising pieces of stone in a cloth

bag with mercury and squeezed the bag

until the quicksilver trickled out. The

material left inside appeared to be pure

gold; it was actually an amalgam, but not

even experts could tell.

An alchemist could also use quicksilver

to separate gold from silver. The process

involved heating a gilt object in mercury,

then rapping it sharply. All gold would

crumble off, leaving the surface below

intact. Other chemists used a powder of

sal ammoniac and sulfur that could be

applied to an object with oil. Gold would

then flake away as soon as the object was

heated. These methods were usually used

by craftsmen who wanted to remake fine

gilt items, but they have obvious applications

for theft. A dose of this solution cost

50 gp and can remove 10 lbs. of gold.

Miners leached salt and chemicals from

their ore. Medieval chemists made lye by

soaking the ashes of reeds and distilling

the water. Saltpeter could be made the

same way, but it came from the earth on

cellar walls and oak ash instead of reeds; it

was usually purified by heating it in a

copper pot. Bitumen did not even need to

be fully dried; it floated to the top of water,

where workers skimmed off the oily

substance with goose wings. Alum came

from certain porous rocks, which were

heated and dissolved in human urine. The

reconstituted material could be used in

many ways. Doctors prescribed alum to

stop bleeding, as mouthwash, and to cure

dysentery. Dyemasters made a remarkable

pigment from alum that did not appear to

have any effect on cloth at first but gradually

became colored. Cloth dipped in a

single vat of alum dye could take on many

different shades. Miners prized salty hot

springs, since these not only contained

minerals but their natural steam could

power an apparatus designed to draw out

water and automatically evaporate it with

geothermal heat. The spring did all the

work; its owner simply came at the end of

each day to collect his minerals.

Smelting is partially described on

page

26 of the DSG. Every 200 gp weight of ore

requires 5 gp worth of fluxes and one

worker. Automatic machinery costs 1,000

gp to install but reduces the need for labor

by one-half. Have the character in charge

of a smelter make a smelting proficiency

check (see the DSG, page 25). Smelters

suffer a +3 penalty on this roll if they

have not successfully assayed the ore. If

the check fails, half of the metal is lost,

and the rest must be resmelted. If the

check succeeds, the character obtains 75%

of the available metal. Smelters must pass

a second check to get the rest.

Table 1

Metallic Ores and Gems

| Ore | Element | Hardness* | Weight** | Notes |

| Argentite | Silver | Soft | 450 | Silvery crystals |

| Bornite | Copper | Hard | 312 | Bronze color, purple sheen |

| Cassiterite | Tin | Hard | 437 | Fibrous masses |

| Chalcocite | Copper | Soft | 344 | Gray-black |

| Cinnabar | Mercury | Soft | 506 | Red, used in dyes |

| Copper, native | Copper | Hard | 556 | -4 bonus on smelting rolls |

| Galena | Lead | Soft | 469 | Gray crystals |

| Gem minerals | Varies | Hard | 162 | See the DSG, pages 51 and 53, for output |

| Gold ore | Gold | Soft | 600 | Gray |

| Hematite | Iron | Hard | 312 | Red stone or gray crystal |

| Limonite | Iron | Hard | 219 | Rounded ochre lumps |

| Magnetite | Iron | Hard | 325 | Black, magnetic (lodestone); see the DSG, page 42 |

| Malachite | Copper | Hard | 231 | Ornamental (azurite) |

| Pentlandite | Nickel | Hard | 287 | Brassy, contains iron: miners once considered it cursed |

| Pyrite | Iron | Hard | 312 | "Fools' gold" |

| Siderite | Iron | Hard | 237 | Brown crystals |

| Skutterudite | Cobalt | Hard | 406 | Gray clusters |

| Sphalerite | Zinc | Hard | 250 | Yellow-brown, brittle |

* “Hard” and “soft” apply to Table 27: Mining

Rates, in the DSG, page 50, and to the

Mining table in the 1st Edition DMG, page 106.

** Figures show the weight of excavated ore in pounds per cubic foot.

The amount of

actual metal extracted from this ore can be determined using Table

2.

Table 2

Ore Purity

1d10 roll*

| Metal | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Cobalt | 5 | 10 | 20 | 40 | 75 | 90 | 110 | 150 | 200 | 250 |

| Copper | 16A | 33B | 41A | 50C | 58 A | 66 C | 83 A | 125 C | 166 D | 333 D |

| Gold | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 50 | 67 | 83 | 125 | 166 |

| Iron | 33E | 50F | 83F | 116F | 150G | 200H | 266G | 333H | 500H | 660H |

| Lead | 16 | 33 | 41 | 50 | 58 | 66 | 83 | 125 | 166 | 333 |

| Mercury | 16 | 33 | 41 | 50 | 58 | 66 | 83 | 125 | 166 | 333 |

| Nickel | 15 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 120 | 170 | 300 |

| Platinum | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 17 | 42 | 67 | 134 | 167 |

| Silver | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 50 | 64 | 83 | 125 | 167 | 166<> |

| Tin | 30 | 60 | 90 | 100 | 130 | 135 | 140 | 150 | 160 | 170 |

| Zinc | 15 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 58 | 66 | 83 | 125 | 166 | 333 |

* Figures show the gold-piece weight of metal per 25 cubic feet of ore

mined.

A = halcocite; B = Malachite; C = Bornite; D = Native copper; E =Siderite;

F = Pyrite; G = Limonite; H = Hematite.

For game purposes, all other minerals come from single ores, as per

Table 1.

Ending a mine

Eventually, miners will have dug all the

metal they can safely take from a mine.

During Roman times, people hoped that

ore would grow back in an exhausted

mine, as if the earth were a living thing

healing its wounds. This might be true on

the elemental plane of Earth in a fantasy

world. However, even Agricola knew that

this was wrong, and he warned that no

one should abandon a mine without leaving

a record of why it was unsuitable.

Many miners wasted fortunes trying to

reopen empty mines. Mines in fantasy

could be abandoned because of gases or

monsters, or because the shafts had nearly

tapped underground lakes or magma. But

many an adventure might unfold as unknowing

characters make their way

though old shafts and tunnelings, in

search of dangerous beasts or lost and

forgotten riches beneath the ground.

Bibliography

Agricola, Georgius (translated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry

Hoover).

De

Re Metallica. New York: Dover Publications,

1950. (Yes, the translator was a President.

This book contains numerous

woodcuts of elaborate late medieval

machinery, much of it

applicable to AD&D campaigns.)

Edwards, Richard, and Keith Atkinson.

Ore Deposit Geology. New York: Chapman

and Hall, 1988.

French, Roger, and Frank Greenaway

(translators and commentators).

Science in the Early Roman Empire. Totowa,

N.J.: Barnes and Noble Books,

1986.

Park, Charles and Roy MacDiamaid. Ore Deposits.

San Francisco: William Freeman

& Company, 1975.

Peters, William C. Exploration and Mining.

Geology New York: John Wiley & Sons,

1978.

Strangway, D. W. The Continental Crust

and Its Mineral Deposits. Waterloo,

Ontario: Geological Association of Canada,

1980.

van Andel, Tjeerd. Tales of an Old Ocean.

Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Alumni Association

Press, 1977.

Zim, Herbert S. and Paul R. Shaffer. Rocks

and Minerals. New York: Golden Press,

1957.

The Wanderers Below

Random encounter tables for the depths of the earth

by Buddy Pennington

Before the DSG was published, underground

delving was

usually limited to artificial settings like

dungeons. Now characters have many,

many miles of caverns and passages to

explore as well.

Unfortunately, there have been no random

encounter tables provided for underground

campaigns. There are tables for

wilderness, oceans, the planes, cities,

manmade dungeons, and even ?for psionic

creatures, but not natural underground

areas. With this in mind, I present a series

of tables to give random encounters when

your players are traveling in the majestic

realms below the earth.

Encounters should be checked for once

every six hours (there is no day or night

underground). There is a 1 in 10 chance of

an encounter, unless noted below. The

number of creatures encountered has

been deliberately left out so you can tailor

the encounter to your party?s level. The

tables are explained as follows:

?Unpatrolled? caverns and tunnels (Table

1) are those with no major communities of

intelligent beings, though small groups of

drow, duergar, etc., may be present.

?Heated? caverns and tunnels (Table 2)

are those that are unbearably hot and

cause damage to most player characters.

(Cooler caves should use Table 1 for random

encounters.) The chance of an

encounter in a heated area is 1 in 8. If a

gateway is rolled, there should be a large

number of creatures, native to the given

plane, near the gate.

Water-filled caverns and tunnels (Table

3) are partially or completely submerged.

A few of these encounters (aboleth, eye of

the deep, etc.) are only found in deep lakes

and rivers. If an unsuitable encounter is

rolled, simply roll again or pick an encounter

from the table. The chance for an

encounter is 1 in 12. Caves with small

streams or pools should use Table 1.

Use Table 4 when PCs are within 20

miles of a duergar city. The chance of an

encounter is 1 in 6.

Use Table 5 when PCs are within 15

miles of a svirfneblin community. The

chance of an encounter is 1 in 8. Beings

and creatures encountered here will usually

be neutral or good in alignment.

Use Table 6 when PCs are within 30

miles of a drow city. The chance of an

encounter is 1 in 6. Demons encountered

should be determined by the DM to challenge

the party. Driders are only found

along the fringes of drow communities, as

they are considered outcasts. Arachnids

are found everywhere, as they are considered

pets. Character parties encountered

here will usually be evil spell-casters seeking

alliances with the drow.

Other tables may be created for the rest

of the underground races, such as derro,

kuo-toa, and so forth. These tables may

also be redesigned to fit each DM?s Underdark

campaign.

Table 1

Unpatrolled Caverns and Tunnels

1d100 Result

01-04 Roll on Table 1.A.

05-12 Roll on Table 1.B.

13-15 Roll on Table 1.C.

16-17 Basilisk

18 Basilisk, greater

19-22 Bat, ordinary

23-24 Bat, giant

25-27 Beetle, giant, fire

28 Beholder

29-30 Blindheim

31-32 Boggle

33-35 Carrion crawler

36 Cave cricket

37-38 Cave fisher

39 Cave moray

40-42 Centipede, giant

43 Character party

44-45 Cockatrice

46-47 Dark creeper

48 Dark stalker

49 Doombat

50 Doppleganger

51-52 Gargoyle

53 Gas spore

54-55 Giant, stone

56 Gibbering mouther

57-59 Hook horror

60 Intellect devourer

61 Khargra

62-63 Lizard, giant, subterranean

64-65 Lurker above

66-67 Lycanthrope, wererat

68-69 Margoyle

70-72 Piercer

73 Purple worm

74-77 Rat, giant

78 Rothe

79-80 Roper

81-84 Rust monster

85-88 Slug, giant

89 Spectator

90 Storoper

91-92 Trapper

93-95 Umber hulk

96-97 Xaren

98-00 Xorn

Table 1.A.

Fungi, Slimes, and Jellies

1d100 Result

01-05 Black pudding

06-14 Fungi, violet

15-20 Gelatinous cube

21-24 Gray ooze

25-35 Green slime

36-44 Mold, brown

45-56 Mold, yellow

57-65 Ochre jelly

66-75 Olive slime

76-00 Shrieker

Table 1.B.

Intelligent Dwellers

1d100 Result

01-06 Bugbear/gnoll

07-10 Cloaker

11-13 Derro

14-16 Drider

17-25 Drow

26-34 Duergar/dwarf

35-46 Goblin/hobgoblin

47-50 Jermlaine/mite/snyad

51-53 Kuo-toa

54-58 Mind flayer

59-61 Myconid

62-70 Ogre

71-75 Orc

76-78 Pech

79-81 Svirfneblin/gnome

82-90 Troglodyte

91-96 Troll

97-00 Xvart/kobold

Table 1.C.

Undead

1d100 Result

01-07 Apparition

08-13 Coffer corpse

14-20 Ghast

21-30 Ghoul

31-34 Huecuva

35 Lich

36-45 Shadow

46-50 Shadow demon

51-65 Skeleton

66-68 Spectre

69-77 Wight

78-84 Wraith

85-86 Vampire

87-00 Zombie

Table 2

Heated Caverns and Tunnels

1d100 Result

01-04 Azer

05-12 Bat, fire

13-17 Elemental, fire

18-20 Efreeti,

21-23 Fire snake

24-27 Firetoad

28-30 Gate to elemental plane of Fire

31. Gate to para-elemental plane

of Magma

32-50. Giant, fire

52-54. Harginn (elemental grue)

55-60. Hell hound

62-64. Lava children

65-70. Lizard, giant, fire

71-74. Magman

75-76. Mephit, fire

77-78. Mephit, lava

79-80. Mephit, smoke

81-82 Mephit, steam

83-86 Para-elemental, magma

87-93 Pyrolisk

94-00 Salamander

Table 3

Water-Filled Caverns and Tunnels

1d100 Result

01-15 Aboleth

16-20 Bloodworm, giant

21-28 Bullywug

29-30 Eye of the deep

31-38 Frog, giant

39-65 Kuo-toa

66-67 Morkoth

68-70 Mudman

71-73 Nereid

74-80 Ogre, aquatic

81-83 Sirine

84-00 Troll, rnarine

Table 4

Duergar Caverns and Tunnels

1d100 Result

01-05 Character party

06-60 Duergar

61-70 Derro

71-00 Use Table 1

Table 5

Svirfneblin Caverns and Tunnels

1d100 Result

01-10 Character party

11-60 Svirfneblin

61-65 Rothe

66-00 Use Table 1

Table 6

Drow Caverns and Tunnels

1d100 Result

01-05 Character party

06-08 Demon

09-19 Displacer beast

20-22 Drider

23-60 Drow

61-64 Pedipalp

65-70 Scorpion, giant

71-75 Spider*

76-00 Use Table 1

* 01-30 giant, 31-60 huge, 61-00 large.

Servants of the

Jewelled Dagger

The lives and habits of the duergar?the gray dwarves

by Eric Oppen

Despite what you?d think, duergar and

surface dwarves have much in common in

AD&D® campaigns, more than do drow

and surface elves but less than svirfneblin

and surface gnomes. This is partially because

cause the duergar lifestyle is not as radically

different from surface dwarven life

as drow life is from other elves. The basic

dwarven nature both races share dictates

many similarities.

The physical differences between dwarf

and

duergar

however, are easily spotted.

The duergar is pale, with a distinct gray

undertone to its skin (unlike the ruddy hill

or mountain dwarf), leading to the nickname

?gray dwarf.? This lack of coloration

is the result of untold centuries spent far

from

the light of the sun, in greater isolation

than their better-known cousins experience.

The relative emaciation of duergar

results from the relative lack of food inthe

underworld?and the quality of what

food they do eat, consisting of subterranean

nean beasts and fungi. Then, too, the

hostile environment of the Underdark

does not allow a fat, slow, clumsy duergar

to survive for long.

Ages of living under these conditions

have made the duergar tougher in stamina

than their surface cousins. Duergar are

able to resist the effects of poison and

paralysis as a result. Their great skills at

surprising foes and resisting illusions come

from ages of life within the twisting labyrinth

rinths of the Underdark, which has sharpened

their senses of hearing, vision, and

smell to exceptional levels. The magical

abilities to enlarge themselves or go invisible

are suspected of being gifts of Abbathor,

their patron deity (see Unearthed

Arcana, page 111).

The psychological differences between

dwarves and duergar are considerable.

Accustomed to lives of hardship and deprivation,

duergar scorn the values of surface

races and of other dwarves. They are

believers in the absolute control of all resources

to benefit themselves, at whatever

cost to other races and beings. They

thus have a penchant for slave labor and

mount many raids to secure more slaves.

In these raids, any beings not currently

allied with the duergar are fair game, and

resistance is overcome with skill and fury.

The fate of these slaves is not enviable;

any duergar slaveowner will treat rebellious

and useless slaves with utter ruthlessness.

Indeed, there are those who say

that duergar have more in common with

orcs than with other dwarves.

Similarities between dwarves and

duergar, however, are so widespread that

former duergar slaves generally find

themselves quite uncomfortable among

surface dwarves. Under circumstances

where dwarves and duergar must get

along, as when they are both slaves of

some other race, they generally find that

they have much more in common with

each other than with nondwarven fellow

slaves, and cooperation between them?

however forced and temporary?is remarkably

smooth and effective.

One cultural trait shared by duergar and

dwarf is their attitude toward the beard,

though this is not universally shared by all

duergar. To those who care, the beard is a

symbol of status and a source of pride.

Cutting or shaving the beard is a mark of

great shame, while burning the beard off

with a coal or candle is reserved for those

who have utterly disgraced themselves or

their clan. As do surface dwarves, duergar

plait their beards and braid them, using

dull-colored strips of leather to indicate

status and profession. These decorations

follow a system, but the systems differ

enough that a duergar and surface dwarf

cannot ?read? each others? beards, except

in the vaguest way. The closest analogy to

this is the widely varying systems of indicating

rank and status used by human

armies; most soldiers can tell an officer

from an enlisted man in an unfamiliar

army, but finer distinctions are difficult to

make.

As noted, not all duergar share this

pride in the beard: Those who do not are

often regarded as uncivilized and the least

worthy of favorable attention?i.e., other

duergar clans will raid those ?prideless?

clans without hesitation.

Another similarity between surface

dwarves and duergar concerns an appreciation

for craftsmanship, Duergar craftsmen

make many of the finest tools, armor,

and weapons available to the underground

races and take great pride in them. Even

the dark elves and deep gnomes, no mean

craftsmen in their own rights, admire the

duergar?s solid, unadorned, but highly

effective creations: As is the case with

surface dwarves, many duergar are so

immersed in their crafts that they have no

desire to marry. However, duergar are

almost exclusively concerned with craftwork

of a hard, practical, military nature,

involving the construction of fortifications

and the smithing of weapons, armor,

traps, and the like. Artistic endeavors are

rarely practiced and tend to be crude,

though even these have a peculiar, harsh

strength in artistic terms.

The duergars? world

Duergar society is highly structured.

The basic unit is the clan, an extended

family of duergar. Most clans are so ancient

that the actual kinship between most

living members is quite remote. A duergar

is highly loyal to his or her clan and will

not willingly betray or weaken it. Duergar

adventurers have great difficulty in transferring

this attitude to their comrades,

seeing them always as ?outsiders.? Given

considerable time and reason for respect,

however, duergar may become quite loyal

to their companions once their comradeship

is won, especially if dwarves or

gnomes of similar alignment and attitudes

are present.

The clan itself is supported by the priesthood

of the duergar community, which is

almost always in the service of Abbathor,

the much-feared dwarven god whose

greed is his hallmark. Little attention is

given to the other major dwarven gods,

and services and offerings to them are

often so minimal as to be insulting.

The clan is also supported by its internal

security force, in some ways a combination

of police, thieves? guild, and assassins?

guild. These carefully trained duergar

rogues and warriors operate under the

direct command of the leaders of a

duergar colony and form the leaders?

intelligence system, warning of danger

outside and dissension within the colony.

Dissident duergar and enemy leaders are

quietly put out of the way.

Duergar professions

Young duergar are put through intensive

testing when they reach adolescence. This

testing, which may prove fatal, has two

purposes. The main purpose is to identify

professions for which a youngster is

suited. The dangerous tests, the duergar

say, also have the side effect of weeding

out weaklings before they can harm the

community.

When the testing is completed, the

youths are sent to rigorous training in a

particular profession. This training is

carefully designed to foster qualities such

as ruthlessness, a racial self-centeredness,

and a disregard for life, mercy, and other

beings.

Duergar priests call themselves the

servants of Abbathor, whose symbol is the

jewelled dagger, and they are permitted to

use daggers as normal weapons (learning

to use them at 1st level). They use their

spells to improve the duergar community

in general: first to aid their own clans,

then to aid any other duergar, then the

priests themselves, then any allies their

clans may have.

The majority of the youth pass through

the hands of the best warriors in the community,

who drill them in the skills of

underground and surface warfare. This

training is considered supremely important,

and many of the best minds the

duergar have are devoted to improving it.

To be selected as a ?trainer of the young?

is one of the highest honors a duergar

warrior can aspire to. The first part of the

training course is spent determining

which students are best with which weapons.

The second part of the course is

devoted to perfecting the students? skills,

and the last part, which is considered the

most important of all, is spent honing the

ruthless attitude of the young warriors.

Ruthlessness, in truth, is the specialty of

the duergar. They make war with ferocity

and duplicity, cheerfully sacrificing allies if

necessary to secure a victory. They will act

cautiously in the presence of powerful

enemies, but they will attack with reckless

courage if a chance of victory is seen.

Their few allies, such as the drow, recognize

that the duergar are prone to

treachery?but treachery is an art among

the drow, who regard the duergar as

narrow-minded and predictable.

Duergar youth with unusual intelligence

and dexterity are usually apprenticed to

local rogues?the spies, assassins, and

scouts of the clan. Besides their functions

as a combined secret police and intelligence

service for the rulers of the community,

duergar thieves are useful to their

community for their skills with locks and

traps (thus gaining the treasures of their

foes). Their climbing skills come in handy

on expeditions into new areas of the underworld.

In some duergar communities,

assassins must be carefully watched because

of the power and skills (and political

pretensions) they have acquired.

Since most duergar have the ability to be

multiclassed, a youth can easily pass

through several courses of instruction,

one after the other. When a youth?s education

has ended, he returns to his clan,

marries if at all so inclined, and is considered

an adult. The clan marks this occasion

with celebration, climaxed by the

initiation of the newest member into full

clan membership.

Duergar life

The various clans composing a duergar

community often do not much like each

other. Their relationships range from

warm friendship to armed neutrality to illsuppressed

hostility. The clerics do their

best to keep matters under control, but

many interclan hatreds run so strong that

usually the clerics merely suppress open

warfare. In these ?cold wars,? assassination

comes onto its own. Accordingly, assassins

?are as highly esteemed among the duergar

as among the drow. When open fighting

between duergar clans occurs, it is often

by arrangement and takes place in a deserted

cavern cleared for the purpose.

This way, the feuding clans can have it out

without endangering the community in

general (not that this always works).

Within a clan, duergar usually plot and

scheme endlessly for advancement. Assassination

of a fellow clan member is

strongly tabooed, but manipulating one?s

?enemy into a situation that is bound to be

fatal is a skill that is much admired. For all

their rough exterior, the duergar are plotters

of incredible subtlety and skill. The

only persons a duergar can usually trust

are a spouse, parents, and children.

Duergar families work closely together,

though they lack affection. Often a husband,

wife, and their adult children will go

adventuring together; the demanding

environment of the underworld, they feel,

is no place for finicky considerations

about keeping ones’ family out of all danger.

There are no safe places.

Clans that are not riven with internal

rivalry still see extremely intense competition

for higher status. In many clans, this

takes the form of ever-more daring mercantile

expeditions to garner greater

wealth. A duergar who has successfully

traded with peoples whom his friends

considered unreachable will be honored

but will soon find those same friends

outfitting expeditions to share the riches

to be had. Trade in the underworld is a

dangerous business. In the depths of the

earth, duergar merchants must be able to

deal with kuo-toa, mind flayers, and creatures

that most surface-dwellers cannot

even imagine. The duergar feel that the

profits make all the risks worthwhile, and

add that the perils of the underworld

merely weed out the incompetent.

Relations with others

As is well known, duergar and other

dwarves regard each other with antipathy,

mostly because of their deep cultural

differences on such issues as slavery.

Their feud is not as bitter as the elf-drow

vendetta but is very real nonetheless. The

duergar call surface dwarves cowards,

weaklings, and “half-dwarves” (as they live

near the surface instead of deep inside the

earth).

Duergar and gnomes do not get along at

all. To the duergar, gnomes are bumptious

little creatures without proper dignity,

who just want to steal treasure. To surface

gnomes, duergar are a greater danger

than orcs because of their intelligence and

skills. Deep gnomes and duergar have

feuded for centuries over living space,

ores, gems, and duergar slave raids. Despite

their smaller size, the svirfneblin

have done well in this feud.

Duergar and elves have mixed relations.

The drow are often the closest allies the

duergar have, and unless two communities

of these races are actually at war, they will

trade materials and information, particularly

on the doings of the more alien underground

races, such as the aboleth,

cloakers, or mind flayers. As if to compensate,

the duergar find surface elves even

more worthless and irritating than do

other dwarves, and they are prone to

torture or slay elves out of hand.

The duergar hardly know halflings exist.

When duergar and halflings cross paths

(which is rare enough), the gray dwarves

often make the mistake of not taking the

halflings seriously, considering the latter

to make poor slaves at best.

One noteworthy area of difference

between surface dwarves and duergar

regards their attitudes toward humanoid

races such as orcs, kobolds, goblins, and

the like. Duergar regard these races as

inferior but useful as fodder if manipulated

properly. Some half-orcs have even

been seen working within duergar communities

as mercenaries (though poorly

trusted ones). Humanoids are also seen as

potential reservoirs of slaves, particularly

when cheap, expendable laborers are

needed. The humanoids’ craftsmanship is

crude, their fighting skill is relatively low,

and they have no claim on duergar

respect—particularly for their lives.

Duergar regard humans with mixed

emotions. On one side, they grudgingly

admire humans with greater skills than

duergar can attain, or with abilities such

as spell-casting that they lack entirely. The

gray dwarves will hire (and closely monitor)

such humans when their services are

needed. At the same time, they fear and

are jealous of humans and have few compunctions

about enslaving or raiding them.

Conclusion

“Strive to survive, and survive to strive”

is a duergar truism. Whether as grim

warriors, crafty thieves, subtle assassins,

or clan-proud clerics, duergar take their

lives very seriously. Duergar of all walks

of life usually exhibit incredible tenacity

and single-mindedness, for which they are

valued by allies—but for which they are

often cursed and never trusted. Theirs is a

spare and unforgiving existence; though

they have no love for it, they have come to

accept it as their fate and will make the

most of it.

[More information on the duergar is

found in the AD&D® 1st Edition Monster

Manual II (page 61), Unearthed Arcana

(page 10), and in the AD&D

2nd Edition

Monstrous Compendium (?Dwarf,

Duergar?).]