| - | - | Out on a Limb | - | - |

| Dragon #26 | - | 1st Edition AD&D | - | Dragon magazine |

The strength

requisite of D&D characters

is often increased, and

sometimes decreased, due to magic

items, potions, the touch of

monsters such as Shadows,

etc. There is a need for a table to show

players and referees what happens when

strength goes above 8/100

and below

3. Some of us refs also hand out girdles of kobold

strength

and gauntlets of pixie

power, and we need monster equivalent strengths

for those. In addition, some monsters often

use weapons and there is a

need to add strength bonuses to their basic

weapons damage in a systematic

way.

The table presented here is an attempt to

meet those needs.

Natural strength can never exceed the racial

maximums given in the

Player’s Handbook, though magic

can temporarily and sometimes

permanently (wishes) increase strength

beyond that. All hit probability

and damage bonuses are cumulative.

This table is to be used in two ways. First,

when monsters use

weapons, one should simply add the monster’s

average racial strength

bonuses from this table to the damage done

according to the Player’s

Handbook Weapon

Table, PROVIDED the monster is man-sized or

larger. If the monster is smaller than

man-sized, use the accompanying

Smaller

than Man-sized Weapons Table and do not add the average

racial strength bonuses given here.

The other method is to roll 3d6 as usual

and add the strength

bonuses from that to the average racial

strength of the monster (including

percentile rolls for 18/? strength). Thus

you can have an exceptionally

strong or weak ogre.

This can be especially important when PCs

are polymorphed into monsters; their personal

strength

bonuses carry over to their monster forms.

This 2nd method should

chiefly be used to add a little individuality

to your monsters.

When monsters are being run as PCs, they

do not

start using the Monsters Attacking Table,

rather they use the Men Attacking

Table, with bonuses for racial strength

and personal strength,

and increase hit probability as they go

up in experience as fighters.

<revised attack

matrix>

Some changes have been made from the Players’

Handbook

Strength

Table. Magic items in the Dungeon Masters’ Guide should be

modified to fit this table; i.e., Gauntlets

of Ogre Power would be plus 3

to hit and plus d6 in damage rather than

plus 2 to hit and plus d8 in

damage. Demons

and devils should have strengths of 20-25

depending

upon type, at the referee’s discretion.

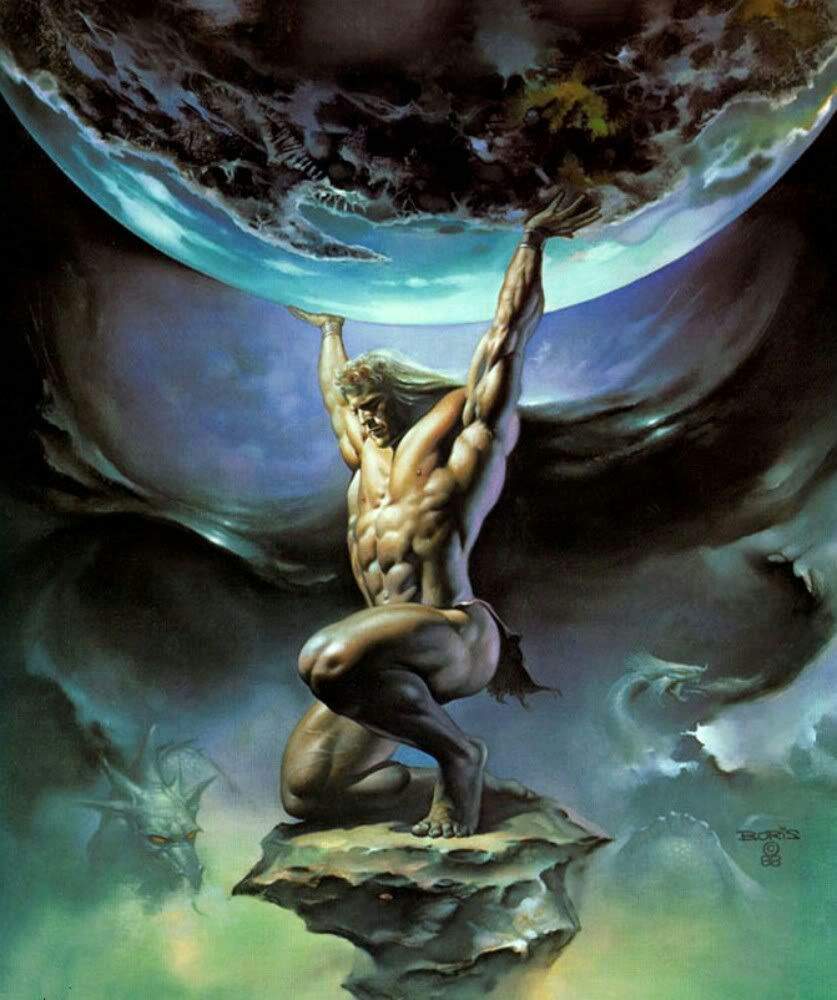

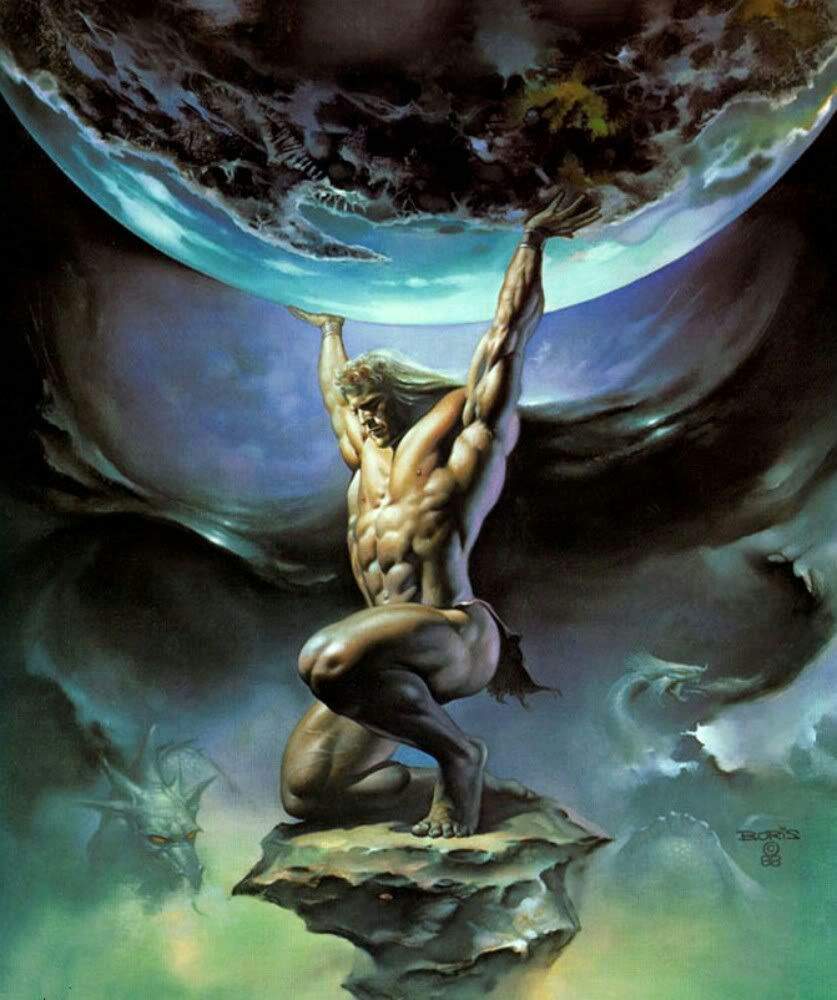

The inspiration for this came from the strength

table in Dave Hargrave’s

Arduin Grimoire II.

Arduin Grimoire II.

| STRENGTH DIE ROLL | EQUIVALENT MONSTER STRENGTH | <MONSTER> | HIT PROBABILITY | DAMAGE |

| 0 | 0 | none | collapse on ground | can't move |

| 1 | 1 | Brownies | -4 | -d6 |

| 2 | 2 | Leprechauns | -3 | -d4 |

| 3 | 3 | Pixies | -2 | -1-3 |

| 4 | 4 | Gnomes, Halflings, Kobolds | -2 | -1-2 |

| 5 | 5 | none | -1 | -1-2 |

| 6-7 | 6-7 | Goblins, Nixies | -1 | -1 |

| 8 | 8 | none | -1 | normal |

| 9-12 | 9-12 | Elves, Humans, Orcs | normal | normal |

| 13-14 | 13-14 | Dwarves | +1 | normal |

| 15-16 | 15-16 | Hobgoblins | +1 | +1 |

| 17-18/01-75 | 17-18 | Lizard Men | +2 | +1-2 |

| 18/76-90 | 19 | Gnolls | +2 | +1-3 |

| 18/90-99 | 20 | Bugbears | +2 | +d4 |

| 18/100 | 21 | Ogres, Trolls | +3 | +d6 |

| - | 22 | Hill Giants, Ogre Magi | +4 | +2-9 |

| - | 23 | Stone Giants | +4 | +2d6 |

| - | 24 | Frost Giants | +5 | +3d6 |

| - | 25 | Fire Giants | +5 | +4d6 |

| - | 26 | Cloud Giants | +6 | +5d6 |

| - | 27 | Storm Giants, Titans | +6 | +6d6 |

There are a lot of aspects of strength

which should be left to the

discretion of the referee. Flesh and bone

are not increased in their

load-bearing properties by magic, so there

is a fairly good chance that

tendons would be ripped, cartilage tom

and bones fractured when

using magically increased strength for

purposes besides melee. A

character might have the strength to pick

up and throw a boulder like a

giant, but his joints would probably fail

messily if he tried. Not to mention

such details as whether or not his arms

and hands are broad

enough to get a grip, if he has the leverage

and balance to get under it

and not fall on his nose, etc.

This table is meant to be used in conjunction

with Smaller than

Man-Sized Weapons Table

for smaller than man-sized characters and

monsters. Example: a hobbit with 16 strength

attacks with a hobbit-sized

Battle Axe. His 16 strength from this table

is one lower than the

maximum possible allowed for hobbits from

the Players’ Handbook

Strength

Table I and is permissible (though not if he suffers a sex change

from magic, in which case it would be reduced

to 14) so he is plus 1 to hit

and plus 1 in damage. The hobbit equivelant

of Battle Axe does one d4

of damage, so this hobbit’s damage is 2-5.

A human cursed with a Girdle of Hobbit

Strength would be minus

2 to hit and minus 1-2 points in damage

with a man-sized battle axe,

modified by a strength of say 16, to minus

1 to hit and minus 1 to

damage, for potential damage of 1-7 points.

The difference is that the

human is using a man-sized axe, which with

his reduced strength is

rather unwieldy, but it is heavier and

has the potential to do greater

damage than the hobbit axe wielded by a

strong hobbit.

Damage can never be reduced below 1 point

no matter how

many reductions there are.

SMALLER

THAN MAN-SIZE WEAPONS TABLE

Thomas Holsinger

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Dragon #29 | - | 1st Edition AD&D | - | Dragon magazine |

Editor’s note: This article was written

in companion with Mr. Holsinger’s

“Strength

Comparison Table” (TD #26). Space considerations

did not allow us to use both in the

same magazine. Both articles should

be read and used in conjunction with

each other. Our apologies for any

confusion or difficulties resulting

from splitting the 2 pieces.

Small creatures which

use weapons, such as hobbits, goblins, etc.,

generally use weapons proportioned to fit

their smaller stature and

these smaller weapons do less damage than

their man-sized counterparts.

It is fairly easy to allow for damage bonuses

due to strength for the

larger than man-sized monsters, but this

is really not possible for smaller

than man-sized critters due to the high

percentage of “one damage

point” results which would ensue from a

simple subtraction from damage

rolls.

The following table is presented to deal

with this problem. It lists

melee weapons in three columns, man-sized

weapons in the first, damage

from weapons for the 3’ high races in the

center (Gnomes, Halflings,

Kobolds) and damage by Goblin-sized weapons

in the last column.

Each column has two entries separated by

a slash (/), the first

being damage to man-sized targets and the

second being damage to

larger than man-sized targets.

This table grew out of an encounter I had

as a referee with the

“barbarian hobbit” one player brought in

and attempted to run as

Conan’s cousin. All the hobbits I had dealt

with in the past were sensible

ones like thieves and assassins who believed

that the best course for a

hobbit was to stay out of sight and do

the deed when no one was looking.

Not this guy. He wanted to have his hobbit

charge in with swords

bigger than his character. I pointed out

that hobbits just aren’t big

enough to use man-sized two-handed swords,

halberds and the like,

and that a pole arm shaft small enough

for a hobbit’s grip would have to

be thinner and therefore weaker than normal.

The twit howled with

indignation and I almost had to throw him

out of the game.

Dwarves are only 4’ high, just as Goblins,

but they are 3’ across and

are very strong for their weight, more

so than humans. They therefore

use the man-sized weapons column.

| WEAPON | NORMAL | GNOMES, ETC. | GOBLINS |

| Dagger | 1-4/1-3 | 1-2/1-2 | 1-3/1-3 |

| Poinard | 2-5/1-4 | 1-3/1-2 | 1-4/1-3 |

| Short Sword | 1-6/1-8 | 1-3/1-4 | 1-4/1-6 |

| Rapier | 2-7/1-6 | 1-4/1-3 | 2-5/1-4 |

| Scimitar | 1-8/1-8 | 1-4/1-4 | 1-6/1-8 |

| Broadsword | 2-8/2-7 | 1-4/1-4 | 2-6/2-5 |

| Bastard Sword | 2-8/2-16 | 1-4/1-8 | 2-6/2-12 |

| Great Sword | 1-10/3018 | 1-5/2-9 | 1-7/2-14 |

| Small Axe | 1-6/1-4 | 1-3/1-2 | 1-4/1-3 |

| Battle Axe | 1-8/1-8 | 1-41-4 | 1-6/1-6 |

| Great Axe | 2-12/4-24 | 1-6/2-12 | 2-9/3-18 |

| 8' Spear | 1-6/1-8 | 1-3/1-4 | 1-4/1-6 |

| 12' Spear | 1-6/1-10 | 1-3/1-5 | 1-4/2-7 |

| 16' Pike | 1-6/1-12 | 1-3/1-6 | 1-4/1-8 |

| Halberd | 1-10/2-12 | 1-5/1-6 | 1-8/2-9 |

| Warhammer/Small Mace | 2-5/1-4 | 1-3/1-2 | 2-4/1-3 |

| Large Mace | 2-7/1-6 | 1-4/1-3 | 2-5/1-4 |

| 2-Handed Mace | 2-9/1-8 | 1-5/1-4 | 2-7/1-6 |

| Military Pick | 2-7/2-8 | 1-3/1-4 | 2-5/2-6 |

| Flail | 2-7/2-8 | 1-3/1-4 | 2-5/2-6 |

| Morning Star | 2-8/2-7 | 1-4/1-3 | 2-6/2-5 |

| Javelin | 1-6/1-6 | 1-3/1-3 | 1-4/1-4 |

| Throwing Axe | 1-6/1-4 | 1-3/1-2 | 1-4/1-3 |

| Sling Stone | 1-4/1-4 | 1-2/1-2 | 1-3/1-3 |

| Self Bow Arrow | 1-6/1-6 | 1-3/1-3 | 1-4/1-4 |

Thomas Holsinger’s STRENGTH COMPARISON

TABLE left me somewhat confused.

He

equated a strength of 18/00 with ogre strength,

which I agree with, (the PSIONICS section of the

PLAYER’S HANDBOOK, under “Expansion”,

states this) but under “Equivalent Monster

Strength” it says “21”. I consider 21 str. vastly

more powerful than a paltry 18/00, & here’s why.

The MONSTER MANUAL states that giants

have

strengths of from 21-30. This doesn’t mean they <19-25>

are stronger than human-types, pound for pound.

They need this extra strength just to be able to

walk, or even breathe!

The feature in TD 13

(written by one Shlump da orc) showed that the

average hill giant weighs in at around 1000 lbs. I

don’t think anyone with 18/00 str. could even

move hauling this much weight, let alone fight.

Certain titans are stronger than average (for titans)

& can inflict 8d6 damage. Since maximum giant

strength is 30, I would put these titans at around

31-34(?). I hardly think trolls are as strong as ogres

& would give them a strength of about 17. Ogre magi

& ettins would rank with the lower 3 classes of

giants, according to their body weights.

TD 23’s

SORCEROR’S SCROLL states that at 19str., creatures <make

& link>

get +3 to hit & +7 damage, and at 20str., +3

to hit & +8 to damage. These figures would rise

sharply beyond 20str. I would like to point out that

the hit prob. & damage bonuses don’t usually

apply to “monsters”, as their hit prob. & damages

are already computed into the charts (e.g. a kobold

needs an 18 to hit a man in plate mail, but a titan

needs only a 4), & if they are using weapons they

probably won’t receive a hit prob. or damage

bonus, as few are adept enough with weapons to

receive any.

I consider dwarves, elves, gnomes, halflings, &

humans to have about the same average strength,

unlike Mr. Holsinger’s table, which gives gnomes &

halflings an average strength of 4!! Anyone who’s

had characters slaughtered by crazed gnomes can

tell you they’re a lot stronger than that. Besides, the

PLAYER’S HANDBOOK shows that the minimum

strengths for either race (male or female)

is 6! I

wouldn’t rate brownies, leprechauns, or pixies so

low either. They may be small, but they aren’t

helpless. All in all, I would rate Mr. Holsinger’s

article as fair. He tries to impose some kind of order

to the rating of various monsters’ strengths, & only

partially succeeds.

Sincerely,

Crain Strenseth — SD

(The Dragon #30)

[edit]

Your comments vis-a-vis the Strength

Comparison

article are best answered

by the author. I

hope to have his reply next month.

—ED.

(Tim Kask)

(The Dragon #30)

[edit]

'Inconsistencies'

Dear Editor,

Craig Stenseth had some comments on my <find

& link>

Strength Comparison article in the Out On A Limb

section of TD #30 which merit a reply.

First, I hope

that TD #29 with the second part of my article

answered some of his questions (the articles were

erroneously published separately). Second, it appears

that those points of my article which he disliked

most are due to a failure of my ideas to mesh

fully with other parts of D&D,

AD&D

and other

articles in The Dragon. My

tables were written in

March of 1978 when most of the other matter he

referred to had not been published. I rewote them

and broke the tables into 2 articles at the urging

of the staff of The Dragon when I submitted them to

TD in the spring of 1979. SO by the time they were

published in the summer of 1979, much had come

out that contradicted what I had written 15 months

before.

Mr. Stenseth almost answered his own question

about the relative strengths of the smaller than

man-sized creatures compared to humans, in his

earlier comments about giant strength. The crucial

point is known to armored warfare types as the

horsepower-to-weight ratio. A 35 kg goblin is much

stronger proportionately than a 65 kg human who

has been afflicted with a girdle of goblin strength.

I assigned an equivalent monster strength of 19

to human strength of 18/76-90, and monster

strength of 20 to human strength of 18/91-99, etc.,

because I felt like doing it that way. Hargrave and

Gygax do it differently with their tables. So what?

My article was clearly labeled a variant and specifically

stated that some changes had been made

from AD&D. Nor is AD&D

consistent; the Monster

Manual does say that giants have strengths of

21-30 but the Dungeon Masters Guide gives them

strengths of 19-24. (The

Monster

Manual figures

are wrong and should agree with the DMG—

see

Monster Manual errata elsewhere in this issue—Ed.)

You can find inconsistencies in everything if

you look hard enough. The rules of AD&D,

and

those of any other fantasy role-playing games, are

just that, rules. They merely provide a means

whereby the players can act out roles within a

fantasy world of the referee’s creation (though

some FRPG rules are tied to specific backgrounds,

such as Empire of the Petal Throne, Runequest

and Chivalry & Sorcery). As such, FRPG rules are

at best attempts to simulate a realistic “feel” in

events such as melee combat. Game designers

have a difficult enough time devising melee mechanics

that are truly realistic when only humans are

involved, without adding impossibly large monsters

to the fighting.

Giants cannot exist as given in AD&D,

for

physiological reasons. Their legs would have to be

much broader in proportion to their height and

their cardiovascular system would be a nightmare.

Giants would not look at all human and probably

could not exist at all. Some game designers make

arbitrary assumptions and write arbitrary rules just

to make things work. Many points have to be compromised

along the way in any game and especially

in a fantasy role-playing game. The difference

between a good and bad FRPG is the skill with

which the designer has made the unavoidable

trade-offs between playability and the “realistic

feel” of play.

My article represented my own gropings in this

direction almost two years ago. I was one of the

outside commentators for the DMG

draft (second

behind Len Lakofka in nonsense submitted) and I

learned a lot about FRPG game design in working

on the project. My present thinking on the subject

of my earlier articles is that distinctions should be

made between damage due to weapon size (and

weight) and wielder strength, and also between hit

points due to body size and hit points due to skill.

This means, however, that we would be talking

about an entirely different game than AD&D

and I

have in consequence started working on my own

FRPG.

Thomas Holsinger <link>

—Turlock, CA

(The Dragon #35)

I hope this reply from the author of the articles

in question clears up any misunderstanding

created when the two were run in different issues of

The Dragon. However, I will take

issue on one

point.

There seems to be some sort of movement

towards “realism” (whatever that means) in

fantasy role-playing game rules. Why? And how

are these new rules less arbitrary than the so-called

“unrealistic” rules?

Fantasy, by the definition of the word, is unrealistic

or improbable. A set of rules for roleplaying

using nothing but the laws of nature (What

would one call such rules? Reality role-playing?)

would prohibit 75% of the material in any currently

available set of rules.

The point is, fantasy role-playing rules are

designed to create a structure in which players can

role-play or “act out” or fantasize, or whatever you

want to call the act of play, actions otherwise

impossible or improbable in reality. Sure, it’s

physiologically impossible for an AD&D

giant to

exist. But is that any more “unreal” than the ability

to cast a fireball? Why worry about it? It’s fantasy!

Now, The Dragon publishes variants to games

in every issue—not that I as editor, or TSR Periodicals

as a division of TSR Hobbies, Inc. feels that

they are necessary to any given game, or that in

some fashion they make the game more “real.”

The Dragon exists as a forum for game players and

to serve the hobby. If a variant improves the mechanics

of a set of rules, or introduces a new,

unknown factor into a game, and thereby provides

more enjoyment for the players, or helps balance

an unbalanced game, it has served its purpose.

But if a variant professes to make a set of fantasy

game rules more “real,” it is merely an exercise

in semantics that results in a contradiction of

term.

I hope Mr. Ho/singer’s FRPG rules eventually

are published commercially so we may all compare

them to other FRPG rules. I, for one, will be very

interested in seeing how his system is more “real.”

—Jake

(The Dragon #35)

Realism 101

Dear Editor:

I believe you misconstrued the nature of my

comments about realism in my letter to Out

On

A Limb in TD #35. I was not saying that the

melee system in my proposed game is more

“real(istic)” than that of AD&D.

My comments

were aimed at Mr. Stenseth’s criticism of my

Strength Comparison Table as being unrealistic.

I was trying to point out that FRPG’s are inherently

unrealistic and the FRPG designers have to

do the best they can under the <CIRCUMSTANCES>.

Your sensitivity to comments about realism

is understandable, though. My hackles go up for

exactly the same reasons. Most people use

“realism” in a loose fashion and do not distinguish

between what Richard Berg called

“Perceived Realism” and “Actual Realism” in

his Forward Observer column in SPI’s MOVES

magazine. Mr. Berg used the terms in a pejorative

fashion and I prefer to define them as “Subjective”

and “Objective” realism because each

is an essential element of game design.

Objective realism is generally that background

information worked into a game which is

objectively quantifiable or generally agreed

upon as being or having been the true state of

affairs. Subjective realism means those details

that the players of a game perceive as being

realistic, whether or not they are objectively

realistic. If the subjective realism is also objectively

realistic, so much the better.

Fantasy games and science-fiction games

are unique in that their designers are allowed to

create their own “objective reality” within certain

limits. This is commonly known as the

process of world-creation. My own term for it is

“game reality.” Game reality differs from objective

reality in that the designer has either altered

certain natural laws (or created new ones), or

altered historical reality (sometimes extrapolating

upon existing history), or sometimes both,

as in TSR’s Gamma World.

It has been my experience that any alteration

by a game designer of historical reality and/or

natural laws, to create his own “game reality,”

must be handled very carefully. Otherwise, the

divergence from objective reality will develop a

snowballing (positive feedback) effect in which

the logical implications and side effects of the

initial alterations will necessarily entail still more

divergences, and greater ones, until the whole

thing spirals out of control and the game is a

shambles. It is therefore necessary when creating

“game reality” to have a precise and limited

game effect in mind and to have a high degree of

intellectual honesty and ruthlessness in weeding

out concepts that threaten to snowball or threaten

other elements of the game.

One of the chief methods used to deal with

problems of this sort is the application of a

special rule to minimize the adverse side effects

of a particular element of game reality. Two

problems tend to crop up with this response. A

proliferation of special rules to compensate for

fundamental defects in design is a good way to

make an otherwise adequate game unplayable.

The other common problem is that special rules

are inherently arbitrary, and the use of them to

minimize flaws in other rules is often perceived

by the players as being unfair. Then they ignore

the special rules they don’t like.

Special rules are best used to add some interesting

details, commonly called “chrome,” to

a game and they are quite useful in that form

though fantasy game designers tend to overdo

it. There will be time, however, when a FRPG

designer has no choice but to use a special rule

as a “quick fix” for an inherent design flaw.

The respect players have for this sort of

“quick fix” will depend in large measure on the

degree to which the designer has been fair and

consistent in the creation of his “game reality.”

All FRPGs employ arbitrary rules and conventions

to deal with the fantasy elements. Arbitrary

lines have to be drawn somewhere between

what is allowable and what isn’t. If one of these

unavoidable arbitrary rules and/or conventions

coincides with a “quick fix” special rule, the

players will often think that the designer is cheating

and they will ignore the special rule. This will

vary from game to game depending on the type

of players a game attracts. D&D

players are an

unruly and fractious lot, while Runequest types

are more respectful of authority. Gary Gygax

may seem a bit testy, but he has good reasons.

I cannot emphasize enough that “realism” is

an irrelevant term when dealing with FRPGs.

Designers create their own reality with such

games, and a better test is how true the designer

has been to the alternative reality set forth in his

game.

Tom Holsinger

—Turlock, CA

(The Dragon #37)

Realism 102

Dear Jake,

In the letter column of TD #35, you asked

a

very good question: “There seems to be some

sort of movement towards ‘realism’ (whatever

that means) in fantasy role-playing game rules.

Why?” You expressed the opinion that fantasy

gaming consists of playing out actions that are

impossible in reality, and that therefore attempts

to be realistic in writing rules for such gaming are

doomed to failure. While I agree in part, I think

you have missed the point.

Granted, certain things cannot exist exactly

as they are portrayed in myth, such as the giants

whose expanded scale is not possible, at least for

creatures like you and me made of ordinary flesh

and bone. Granted, magic doesn’t work in our

world, at least not as dependably as technology.

Does this make an attempt at realism impossible?

No, it does not. Fantasy gaming at its best

allows the gamer to participate in living through

a fantasy story, and for that reason some of the

rules that apply to story writing apply to fantasy

gaming. One of these is the necessity of main-

taining in the reader or gamer the “willing suspension

of disbelief” that allows one to accept

the premises of the situation in order to enjoy the

story. Ursula K le Guin recently put this very

well in a book review in The Washington Post’s

Book World, page five, on March 23, 1980:

“Effective works of fantasy are distinguished by

their often relentless accuracy of detail, by their

exactness of imagination, by the coherence and

integrity of their imagined world—by, precisely,

their paradoxical truthfulness. . . . An infallible

sign of amateur or careless fantasy writing is the

blurred detail, the fudged artifact, the stupid

anachronism that proclaims, ‘This is just a fantasy,

folks, so it doesn’t really matter.’ It matters

more in fantasy than anywhere else, since in

fantasy we stand on no common mundane

ground, but have only the fantasist to trust. . . If

he lets us down—pffft.” The success of the author

to convince us that everything else is true to

life is a necessary element in storytelling, for

without it we will not be willing to take the next

step and believe the fantastic parts of the story,

be it magic spells, monsters, or whatever.

When someone writes that part of the rules

to a fantasy game are “unrealistic,” what the

underlying complaint comes down to is that the

rules do not allow the user to move freely

through the fantasy. If you are constantly being

startled by false details that shock you into stopping

and asking, “Does it really work that way?”

then the game designer has not done a good job

on that rule. This is why I find the expression that

“It’s just a fantasy” so exasperating when it is

used to explain part of a game—it shows that the

person who falls back on that excuse does not

understand the essence of the subject. The ideal

set of rules would allow the gamer to feel the

armor on the character’s body and the bite of the

sword, the smell of sweat and the pounding of

the blood as you race up the hill. Realism of any

sort is the kind of detail that helps convince you

that the story you are in is truthful in its essence,

even if the details are not true to what we think of

as the real world. Fantasy, to be successful, must

be taken seriously by all concerned designer,

GM, and gamer. So I hope you will try to show a

bit more sympathy to the poor souls who write

you asking for more realism in their games, for

their complaint is not frivolous.

Of course, it is impossible to completely

simulate every detail of real life in a game. You

would be flooded with more data than you could

handle, or would ever want to. But game rules

can be written in such a way as to aid the gamer

instead of presenting roadblocks to enjoyment. I

would like to see more effort put into writing

rules in two parts, the basic mechanics of play

plus an explanation of what the designer was

trying to simulate with that rule. This would get

the gamer to thinking about what’s happening in

the game instead of worrying so much about

mechanics, and should help with that “willing

suspension of disbelief.”

John T. Sapienza, Jr <link>

—Washington, D.C.

(The Dragon #37)

Semantics 201

I seemed to have opened a can of worms

with my reply to Mr. Holsinger’s letter

in TD

#35 regarding realism in fantasy role-playing.

Perhaps I should have been a bit more detailed

in my reply.

Both Mr. Holsinger and Mr Sapienza feel I

missed the point of the letter—perhaps so, but

Mr. Holsinger’s original letter used phrases such

as ". . . melee mechanics that are truly realistic. . ."

and ". . . the unavoidable trade-offs

between playability and the 'realistic feel' of

play . . ." Maybe I'm arguing semantics, but I

still refute the concept of "realism" in FRPGs;

call it "rationalized in a

more logical fashion" and I might buy it (although

whose logic do we use?), but not "more

realistic."

Actually, it seems that, in principle, Mr.

Holsinger, Mr. Sapienza, and I all agree, as they

both provide qualified definitions of what they

refer to as “realism,” Mr. Holsinger with his

terms of “objective realism” vs. “subjective

realism” or as he culls it, “game reality,” and Mr.

Sapienza with his “. . . realism of any sort is the

kind of detail that helps convince you that the

story you are in is truthful in its essence. . . .” I

personally prefer the term “rationalize,” which

my dictionary defines as “‘to bring into accord

with reason or cause something to seem

reasonable.”

OK, semantics aside, rationalization, or

game reality, or whatever, is of extreme importance

in fantasy role-playing game design. As it

happens, when I co-authored GAMMA

WORLD, I was responsible for writing the introductory

material that sets up the environment of

the game, extrapolating, or “rationalizing,” if

you will, the reasons for the game being played

in the environment it is. I felt I could accept the

possibility of man nearly destroying his world,

then being forced to survive in the remains. But

it is still fantasy--I could just have easily set

forth an invasion of aliens from Cappella blowing <capella=x>

away the Earth, and set the same scenario.

The rationalization would have been less effective,

but the setting of the game would not have

been any less "real."

The key to a good fantasy role-playing

game, or a good fantasy novel, as Mr. Sapienza

points out, is the “willing suspension of disbelief.”

This requires a careful rationalization of

the facts as they are put forth to the player or the

reader. In the case of GAMMA WORLD, I felt it

was harder to willingly suspend my disbelief of

aliens from Cappella than it was to accept man’s

penchant for violence over such intangibles as

political and theological ideologies. Thus, GW

has the intro it has.

Alright, having beaten that horse enough, on

to my next point of disagreement: Where is the

justification for the statement “D&D players are

an unruly and fractious lot while Runequest

types are more respectful of authority.”? I am

unwilling to suspend my disbelief of a sweeping

generality.

—Jake

(The Dragon #37)