The Dragon 33

The Dragon 33

| FN: Paradise for painterly people | The Eyes of Mavis Deval, by Gardner F. Fox | FtSS: AD&D's Magic System: How and why it works | LTH: Smoothing

Out Some Snags

In the AD&D® Spell Structure |

Mapping the

Dungeons II: The International DM List for 1980 |

| BotB: Magical Oils: Try Lotions Instead of Potions | DB: Frosts | A CAU for NPC's

Gives Encounters More Believability |

Clerics, take note:

“No Swords” means No Swords! |

Inert Weapons |

| - | - | - | - | Dragon |

From

the Sorcerer's Scroll:

AD&D's

Magic System:

How

and Why It Works

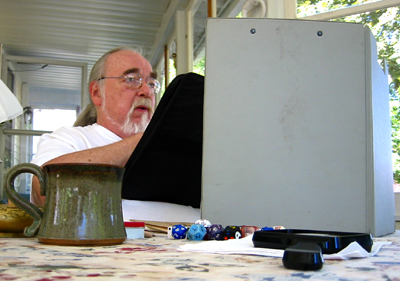

©Gary Gygax

Working up rules about make-believe can

be difficult. Magic,

AD&D

magic, is most certainly make-believe. If there are “Black

Arts”

and “Occult Sciences” which deal with

real, working magic spells, I

have yet to see them.

Mildly put, I do not have any faith in

the powers of magic, nor have I

ever seen anyone who could perform anything

approaching a mere

first-level AD&D

spell without props. Yet heroic fantasy has long

been one of my favorite subjects, and

while I do not believe in invincible

superheroes, wicked magicians, fire-breathing

dragons, and the

stuff of fairie, I love it all nonetheless!

Being able to not only read about

heroic adventures of this sort, but also

to play them as a game form,

increased the prospects of this enjoyment

of imaginary worlds. So

magic and dragons and superheroes and

all such things were added to

Chainmail.

Simply desiring to play fantasy-based games

does not bring them

into being as a usable product. Most of

the subject matter dealt with has

only a limited range of treatment. Thus,

giants are always written of as

large and not overly bright, save in Classical

mythology, of course.

Some are LARGE, and some are turned to

stone

by sunlight, and so

on, but the basics were there to draw

from, and no real problems were

posed in selecting characteristics for

such creatures in a game. The

same is basically true for all sorts of

monsters and even adventurers—

heroes, Magic-Users, et al.

Not so with magic. There are nearly as

many treatments of magic as

there are books which deal with it.

What approach to take? In Chainmail,

this was not a particularly

difficult decision. The wizard using the

magic was simply a part of an

overall scheme, so the spells just worked;

a catapult hurled boulders

and a wizard fire balls or lightning bolts;

elves could move invisibly,

split-move and fire bows, and engage monsters

if armed with magical

weapons, while wizards could become invisible

or CAST spells.

When it came time to translate the rather

cut-and-dried stuff of

Chainmail’s “Fantasy Supplement”

to D&D, far more selection

and

flexibility had to be delivered, for the

latter game was free-form. This

required me to back up several steps to

a point where the figure began a

career which would eventually bring him

or her to the state where they

would equal (and eventually exceed) a

Chainmail

wizard. Similarly,

some basis for the use of magic had to

be created so that a system of

spell acquisition could be devised. Where

should the magic power

come from? Literature gave many possible

answers, but most were

unsuitable for a game, for they demanded

that the spell-caster spend

an inordinate amount of time preparing

the spell. No viable adventurer

character could be devised where a week

or two of preliminary steps

were demanded for the conjuration of some

not particularly mighty

spell. On the other hand, spell-casters

could not be given license to

broadcast magic whenever and wherever

they chose.

This left me with two major areas to select

from. The internal power,

or manna, system where each spell-caster

uses energy from within to

effect magic, requires assigning a total

point value to each such character’s

manna, and a cost in points to each spell.

It is tedious to keep track

of, difficult to police, and allows Magic-Users

far too much freedom

where a broad range of spells are given.

If spell points were to be used,

it would require that either selection

be limited or all other characters

and monsters be strengthened. Otherwise,

spell-users woud quickly

come to dominate the game, and participants

would desire to play only

that class of character. (As a point of

reference, readers are referred to

the handling of psionic abilities as originally

treated in Eldritch Wizardry.

Therein, psionic manna was assumed, the

internal power usable to

tap external sources, and the range of

possible powers thus usable was

sharply limited.)

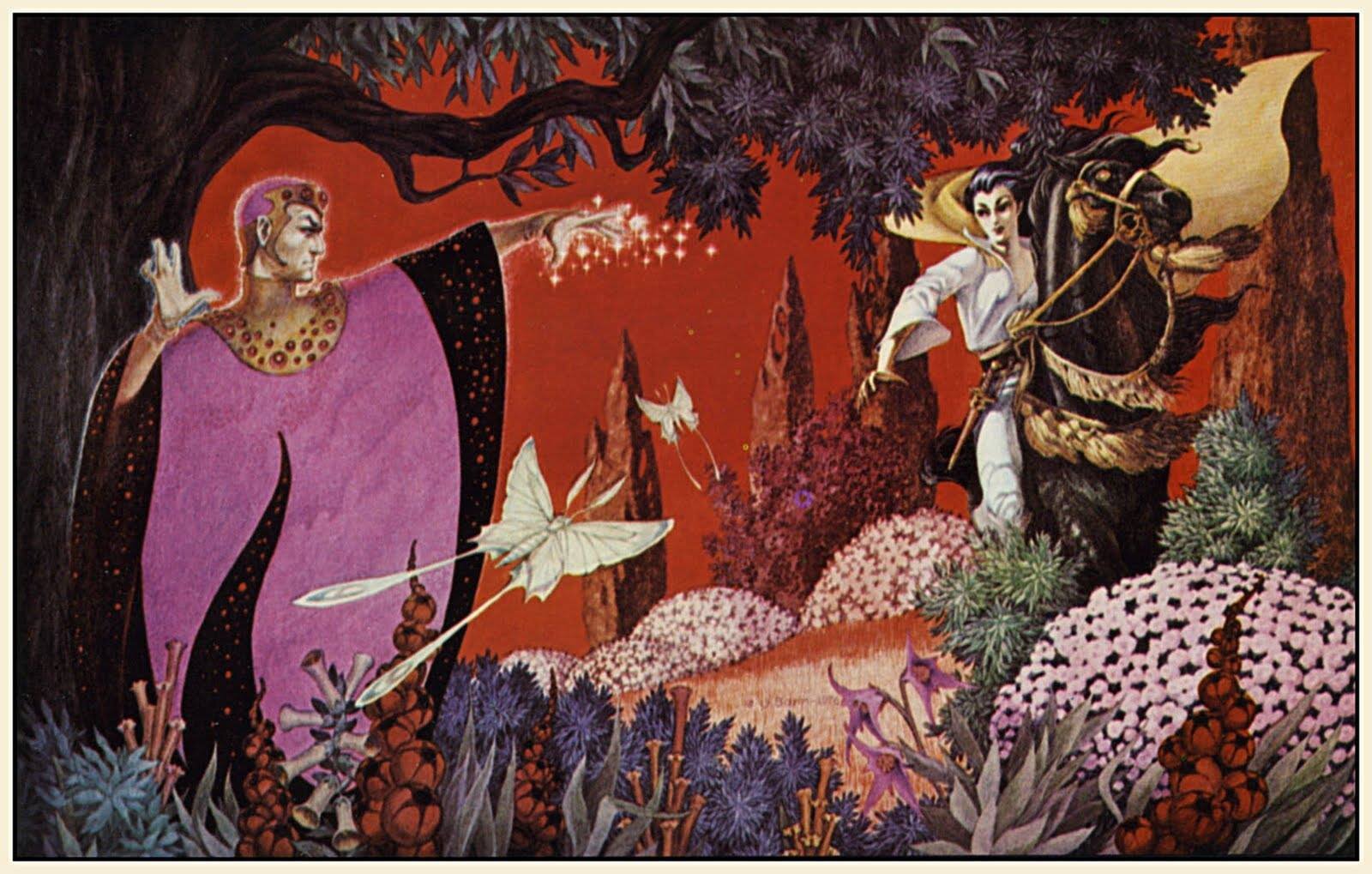

Having read widely in the fantasy genre

since 1950, I opted instead

for the oft-used system which assumes

that magic comes from power

locked within certain words &&

phrases which are uttered to release

the force. This mnemonic power system

was exceedingly well articulated

by Jack Vance in his superb The Eyes

of The Overworld and

Dying Earth novels, as well as

in various short stories. In memorizing

the magical words, the brain of the would-be

spell-caster is taxed by the

charged force of these syllables. To increase

capacity, the spell-caster

must undergo training, study, and mental

discipline.

This is not to say that he || she ever

understands the words, but the

capacity to hold them in the memory and

to speak them correctly

increases thus. The magic words, in turn,

trigger energy which causes

the spell to work.

The so-called “Vancian” magic system allows

a vast array of spells.

Each is assigned a level (mnemonic difficulty)

rating, and experience

grades are used to expand the capacity

of the spell-caster. The use of

this particular system allows more restrictions

upon spell-casting character

types, of course, while allowing freedom

to assign certain spells to

lower difficulty factor to keep the character

type viable in its early

stages. It also has the distinct advantages

of requiring that spell-users

select their magic prior to knowing what

they must face, and limiting

bookkeeping to a simple list of spells

which are crossed off as expended.

The mnemonic spell system can be explained

briefly thus: Magic

works because certain key words and phrases

(sounds) unlock energy

from elsewhere. The sounds are inscribed

in arcane texts or religious

works available to spell-users. Only training

and practice will allow

increased memory capacity, thus allowing

more spells to be used. Once

uttered, the sounds discharge their power,

and this discharge not only

unlocks energy from elsewhere, but it

also wipes all memory of the

particular words or phrases from the speaker’s

brain. Finally, the

energy manifested by the speaking of the

sounds will take a set form,

depending on the pronunciation and order

of the sounds. So a Sleep

spell or a Charm

Monster spell is uttered and the magic effected. The

mind is wiped clean of the memory of what

the sounds were, but by

careful concentration and study later,

the caster can again memorize

these keys.

When Advanced Dungeons

& Dragons was in the conceptualization

stages some three years ago, I realized

that while the

“Vancian” system was the best approach

to spell-casting in fantasy

adventure games, D&D did not go far

enough in defining, delineating,

and restricting its use. Merely having

words was insufficient, so elements

of other systems would have to be added

to make a better

system. While it could be similar in concept

to the spell-casting of D&D,

it had to be quite different in all aspects,

including practice, in order to

bring it up to a higher level of believability

and playability with respect

to other classes.

The AD&D

magic system was therefore predicated on the concept

that there were three power-trigger keys-the

cryptic utterances, hypnotic

gestures, and special substances—the verbal,

somatic,

and

material components, possible in

various combinations, which are

needed to effect magic. This aspect is

less “Vancian,” if you will, but at

the same time the system overall is more

so, for reasons you will see

later.

Verbal spell components,

the energy-charged special words and

phrases, are necessary in most spells.

These special sounds are not

general knowledge, and each would-be spell-caster

must study in order

to even begin to comprehend their reading,

meaning, and pronunciation,

i.e., undergo an apprenticeship. The basic

assumption of this

training is the ability to actually handle

such matter; this ability is

expressed in intelligence or wisdom minimums

for each appropriate

spell-using profession.

Somatic spell components,

the ritual gestures which also draw the

power, must also be learned and practiced.

This manual skill is less

important in clericism, where touching

or the use of a holy/unholy

symbol is generally all that is involved,

while in the Illusionist class it is of

great importance, as much of the spell

power is connected with redirection

of mental energy.

Material components are

also generally needed. This expansion

into sympathetic magic follows the magic

portrayed by L. Sprague de

Camp and Fletcher Pratt in their superb

“Harold Shea” stories, for

example. Of course, it is a basic part

of primitive magic systems practiced

by mankind. In general, some certain material

or materials are also

needed to complete the flow of power from

the spell-caster, which in

turn will draw energy from some other

place and cause the spell to

happen.

now do considerable studying, but he or

she must also have the source <>

material to study. AD&D

also assumes that such material is hard to

come by, and even if a spell-caster is

capable of knowing/memorizing

many and high-level spells, he or she

must find them (in the case of

Magic-Users and Illusionists) or have

the aid of deities or minions

thereof (in the situation faced by Clerics

and Druids). These strictures

apply to other professions which are empowered

with spell use, as

appropriate to the type of spells in question.

In order to expand

mnemonic capacity, spell-users must do

further study and be trained.

Thus, the system is in some ways more

“Vancian,” as such information

and studies are indicated, if not necessarily

detailed, in the works of that

author. It might also be said that the

system takes on “Lovecraftian”

overtones, harkening to tomes of arcane

and dread lore.

In addition to the strictures on locating

the information for new

spells, and the acquisition of the ability

to CAST (new, more powerful)

spells, the requirements of verbal, somatic,

and material components in

most spell-casting highlight the following

facts regarding the interruption

and spoiling of spells: Silencing the

caster will generally ruin the

spell or prevent its instigation. Any

interruption of the somatic

gestures—such as is accomplished by a

successful blow, grappling,

overbearing, or even severe jostling—likewise

spoils the magic. Lack of

material components, or the alteration

or spoiling thereof, will similarly

cause the spell to come to naught.

Of course, this assumes the spell has the

appropriate verbal, somatic,

or material components. Some few spells

have only a verbal

component, fewer still verbal and material,

a handful somatic and

material, and only one has a somatic component

alone. (Which fact will

most certainly change if I ever have the

opportunity to add to the list of

Illusionists’

spells, for on reflection, I am convinced that this class should

have more spells of somatic component

only—but that’s another

story.)

All of these triggers mean that it is both

more difficult to cast a spell,

especially when the new casting time restrictions

are taken into account,

and easier to interrupt a spell before

it is successfully cast.

Consider the casting of a typical spell

with V,S, and M components.

When the caster has opportunity and the

desire to cast a spell, he or she

must utter the special energy-charged

sound patterns attendant to the

magic, gesture appropriately, and hold

or discard the material component(

s) as necessary to finally effect the

spell. Ignoring the appropriate

part or parts, all spells are cast thus,

the time of conjuration to effect the

dweomer varying from but a single segment

to many minutes or tens of

minutes. These combinations allow a more

believable magic system,

albeit the requirements placed upon spell-casters

are more stringent,

and even that helps greatly to balance

play from profession to profession.

A part and parcel of the AD&D

magic system is the general classification

of each spell by its effect. That is,

whether the spell causes an

alteration,

is a

conjuration/summoning,

enchantment/charm, etc. This

grouping enables ease of adjudication

of changes of spell effects or

negation of power. It also makes it easier

to classify new spells by using

the grouping.

It seems inevitable that the classification

and component functions

wil eventually lead to further extrapolation.

The energy triggers of

sound and motion will be categorized and

defined in relation to the

class of dweomer to be effected. This

will indicate what power source is

being tapped, and it will also serve to

indicate from whence the magic

actually comes, i.e., from what place

or plane the end result of a

successfully cast spell actually comes.

Perhaps this will lead to a spellcasting

character having to actually speak a rime,

indicate what special

movements are made, and how material components

are used. While

this is not seriously proposed for usual

play, the wherewithal to do so

will probably be available to DMs whose

participants are so inclined.

It all has a more important and useful

purpose, however. Defining

the energy triggers will make it possible

to matrix combinations by class

of spell-caster and dweomer group. Mispronounced

spells, or research

into new spells, will become far more

interesting in many ways if and

when such information is available and

put into use!

As it now stands, the AD&D

magic system is a combination of

reputed magic drawn from works of fiction

and from myth. Although

they are not defined, verbal and somatic

components are necessary

energy-triggers. The memorization of these

special sounds and motions

is difficult, and when they are properly

used, they release their

small stores of energy to trigger power

from elsewhere. This release

totally wipes all memory of sound and/or

motion from the memory of

the spell caster, but it does not otherwise

seriously affect his or her

brain—although the mnemonic exercise of

learning them in the first

place is unquestionably taxing. Duplicates

of the same spell can be

remembered also, but the cast spell is

gone until its source is again

carefully perused.

The new form which spell casting has taken

in ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS has a

more realistic flavor to it—unimportant,

but some players revel in this sort of

thing, and that is well enough. Of

real importance, however, is the fact

that it requires far more effort from

spell-casters in gaining, preparing, and

casting spells. It makes them

more vulnerable to attacks which spoil

the casting of the spell. All in all,

it tends to make each and every profession

possible for characters in

AD&D to be more equal, but still very

different, from all of the others.

Lastly, it opens up new areas where new

development can be done at

some future time, and if such new material

adds significantly to the

enjoyment of the game, it will certainly

be published—in experimental

form herein, then possibly in final form

in a revised edition of the work

itself.

If the foregoing doesn’t completely explain

everything you or your

players wish to know about the AD&D

magic system; if after all of those

words there are still unanswered questions,

doubts, or disputes, remember

the last and overriding principle of the

whole: ITS MAGIC!

OUT ON A LIMB

This brings me to a point that I didn’t

want to

write about when I started this letter: spell points.

I HAVE HAD ENOUGH OF FORGETTING

SPELLS!!!!!!!

You reject spell points out of hand because one

author uses a system whereby the spell is forgotten

after casting. No other author uses such a system.

To allow a mage to repeatedly cast a spell you

make powerful implements such as wands, staves

and rings. This makes two different magic systems

(forgetting and storing) into one dubious believability

and playability. I have seen dungeons where a

mage walks in with a wand of magic missiles containing

20 charges that the DM used as a treasure

because once the spell is used it is forgotten. For

want of spell points one multiplies MU implement

use incredibly.

And what of illiterate MUs? The Druid in D&D

can somehow have a spell book, although his historical

counterpart could not read. The absurdity is

worsened by the material component rule. Spell

points require less paperwork than do Sears catalogs

of spell material components. If you would just

look at the ease of recording current power next to

current hit points in the game Runequest you

would understand what I am saying.

One of the abilities of a good company is flexibility.

I see little flexibility in TSR as regards rules

innovations. AD&D is different

enough from D&D

to be an entirely new game. Some of the loopholes

have been closed, but the newness is, to some

extent, a facade.

You may consider this a hostile attitude. It is

not. I am not a hostile APA reader with an axe to

grind. I merely think that the game would more

than likely improve if you innovated. I like it when

SPI innovates. I have played their small unit tank

games from Kampfpanzer to Mech War to October

War to the new Mech War. Each is a new

and better

game. I don’t stop playing one because the system

is ‘dated’, but I do appreciate the October War was

not a Mech War with a yellow map.

The graphics on AD&D may be

excellent, but it

still is mostly a ‘yellow map’ D&D.

Glitches are still

there.

Another problem I see with TSR is the problem

of ripping off of game systems and calling them

new. You get altogether too upset about such

things. Saving throw is not a new idea. Role playing

is not a new idea. Level and exp. points may be,

but as ideas they cannot be effectively held onto.

The same goes for 3d6 characteristics. It doesn’t

help a game that much to leave home the old ideas

that work. A comparable demand would be Avalon

Hill saying, “We first quantified strengths and

made the odds CRT. That’s ours now.” I don’t buy <CRT=?>

these kinds of arguments.

Nor can you complain if other game systems

have door locking spells, for Gandalf uses the spell

in LOTR against the Balrog.

A lot of fandom would appreciate you more if

you would calm down and not spend pages of The

Dragon yelling at APAs. We know that you have

hassles, but I don’t plunk $2 on the counter for

yelling in print. Do it by the mail or by the courts.

I’ve heard enough of if.

Marc Jacobs

[edit]

(The Dragon #28)

Unfortunately for you, D&D

was based, the

magic aspect of it, upon Jack Vance’s concepts of

magic in his “Dying Earth” books. That is the way it

is designed. If you don’t like it, play something else,

or design your own variant. Most people make

mages far too powerful, and badly unbalance the

game in so doing. As to the magic items extant in

any given campaign, that is solely the province of

the DM.

Who says that one of the “abilities of a good

company is flexibility”? You? Who are you to say

something that absurd? Where do you think you

are? Since when does a company work on your

principles? We may live in a democracy, but that

democracy does not extend into the field of

business? Is Parker Bros. a bad company because

they resisted the appeals to rename the streets in

MONOPOLY? How can you possibly make such

an asinine claim? Your reference to SPI is hardly

justified. Their specialty is re-doing games time and

time again, and in that context they are successful. I

might add that they also publish the more exotic

and less-demanded off-the-wall games that we

would not otherwise have access to, for which I, as

a gamer, am grateful. By your reasoning, Avalon

Hill is a “bad company” because they have not let

any of their “classics” (which are replete) with

inconsistencies and quirky glitches) be tampered

with.

Kindly document the use of saving throws prior

to a TSR game. You can’t . . .

We can complain about a lack of daring and

ingenuity in game design anytime we wish, by the

same right that you have to make these statements.

We certainly have the right to decry the trend to

take other companies’ ideas and merely rehash

them or slightly modify them. Why is it that when

TSR Hobbies puts out something new and radical,

six months later three or more so-called “improved” designs are

on the

market? I feel that it is symptomatic of a lack of daring and ingenuity

on

the part of the industry as a whole that one or two companies should

do

all the trail blazing and inventing, only to have the rest of them

jump on

the bandwagon made popular by those that took the risks.

If you want a world that is dominated by goblins, instead of having

men be the dominant race, that is up to you. Unless they are somehow

PC’s it is ludicrous to advance lower races, and serves no useful

purpose.

If the lower orders were capable of advancement, man would not

be the dominant species.

Having printed all of this, in context, I wouldn’t want to bet on

who

received any favor. I’m sure that the readers have enough evidence

to

make up their own minds now . . . . — Ed. <Tim

Kask> [edit]

'The best around'

Dear Editor:

I just received a copy of the January issue of

“The Dragon,” and I would have to say that it is the

best fantasy mag around. My favorites are

“Wormy” and “Bazaar of the Bizarre.” Hope

you’ll keep the “Wormy” series for a long time.

Sorry to hear about the “Sorcerer’s Scroll’s” discontinuation,

maybe Mr. Gygax will pick it up once

TSR’s sales drop a bit (Thor forbid!).

A big cheer for

“Clerics and Swords,” “Sage Advice,” and

“Leomund’s Tiny Hut;” even

though I don’t agree

with all they had to say, any AD&D

insights are

very welcome.

One of the few things I didn’t like about the

issue was the cover. What was that thing supposed

to be? Certainly not a dragon, because where was

all the treasure? A basilisk maybe? Anyway, that’s

just a trivial complaint compared to the vast majority

of excellent articles as well as artwork #33

included.

Re “The Electric Eye,” the little excerpt from

the game sounded quite a bit like a program that

we have on our school computer called “Adventure,”

which is a very good version of a D&D

game, with the DM being an all-powerful djinni—

any connection? I agree with Mr. Herro’s views, I

myself having developed an AD&D player creating

program that eliminates a lot of the hassle involved

with that part of the game. I hope to see more of this

sort of thing—maybe leading to a complete

campaign program? Who knows?

John C. Coates IV

—Lynchburg, VA

(The Dragon #36)

Glad you liked the January issue. You’ll be

happy to know that though TSR’s business is continuing

to boom, Gary has managed to produce

a

few more Sorcerer’s Scrolls for us (in case you

missed it, the first return of the Sorcerer’s Scroll

appeared last month, and you’ll find another in this

month's magazine).

The ELECTRIC EYE column has been very favorably

received, and will hopefully be expanded in

the future—just how far remains to be seen. Ideally,

we would like it to touch on all aspects of electronic

games and gaming, including, perhaps,

actual programs. However, we will most likely start

with commercially available equipment and software

before getting into any custom programs.

As for the cover of the January magazine, who

says that dragons must always be surrounded by

treasure??? If you read “Cover-to-Cover” that

month, you know that the title of the painting is

“Dragon’s Lair,” not “Dragon’s Treasure Room.”

Maybe its the dragon’s dining room. In game playing

or in real life, it’s a dangerous business to let

your mind become locked into a single or absolute

concept of how something should appear or

behave—therein lies the path to stereotyping and

prejudice, not to mention that creature you encounter

in the dungeon which outwardly appears

to be a fist-sized rock, but in actuality is a bizarre

creature whose touch is instantly fatal to AD&D

characters played by people named John. Q.E.D.

—Jake

(The Dragon #36)

Quote:

Originally Posted by Reynard

Gary:

A friend of mine let me borrow "Best of Dragon" Vol II (as I am on a bit of an old dragon magazine binge right now) and I just read your essay on D&D's Vancian magic system and why it was created the way it was.

Pure awesome.

Thanks.

I am pleased that you enjoyed

the article.

The "memorize then fire and

forget" principal for casting spells Jack Vance assumed in his fantasy

stories seemed perfect to me for use by D&D magic-users.

IT required forethought

by the player and limited the power of the class all at once.

I still like the concept

even though I have gone to a manical energy point system in the Lejendary

Adventure RPG.

Cheerio,

Gary

B:

A

by

Invisibility

While violence causes the instant negation

of Invisibility, I think that

other magics do so also. I rule that if

a Magic-user is invisible he/she will

become visible in the segment during which

he/she discharges a magic

item or begins to cast any spell. Also,

an invisible figure can not receive

another spell without negating the invisibility.

Thus a figure can be

enlarged, strengthened, hasted and then

made invisible, but Invisibility

MUST be the last spell throw or it is

negated at once! Note that a figure’s

“gear” is not equivalent to another figure.

“Gear” above and beyond

normal encumbrance will not become invisible

and will spoil the effect

of the entire spell. Lastly, “gear” can

not be passed around to others

and remain invisible. The trick of giving

all weapons to the Magic-user

to hold while Invisibility is cast and

then passing the invisible weapons

back to the other players is unfair. Invisibility

can be used to make an

individual weapon, its scabbard (holder)

and belt invisible, of course.

Drawing the weapon will negate the invisibility.

<

* if you TARGET an invisible figure with

a spell, that creature is made invisble (technically, TARGET the square

where the invisible creature is located, in many cases)

* if you are invisible and you CAST a

spell, then your invisibility ends

* if you are invisible and you USE a magic

item, then your invisibility ends

>

<

I covered all the invisibility stuff

over on the EN world boards thread, and in general I agree that any offfensive

action,m including casting a apell or picking a pocket breaks the spell.

Len could have simplified the "gear" question by simply saying that invisibility

covers the person upon whom it is cast as well as all normally worn and

carried by the individual.

If that doesn't cover it, come on back.

- Gary Gygax, Dragonsfoot (1)

>

Clerics,

take note:

“No Swords” means

No Swords!

Lawrence Huss

Excerpts from a lecture at the Seminary

of Magpidar, “On the Use of

Physical Duress” by Archmadriate Bex of

Geopolis.

“. . . so young clerics

say to me, ‘If we may righteously use mace or

flail to remonstrate on our enemies, why

then do we not use sword or

arrow?’

“Why, ‘tis as plain as the forbidden pikestaff!

The purpose and

nature of all edged weapons (and what

is a point but a section of an

edge?) is to cut, release blood

and kill, both in reality and symbolically.

“The club, mace and flail are but growths

of the staff, which stands

for guidance and religious authority.

Though the end result of the

sword stroke and the well-aimed mace blow

are the same, the symbolic

intent differs. As the High Power judges

our acts much from a

viewpoint in which symbols supersede particulars,

this symbolic differ-

ence in intent is of greatest importance,

both to the performance of the

specifically clerical functions and in

the gaining of spiritual eminence.”

In lay terms, the use of edged or pointed

weapons has a different

theological potency than the use of non-edged

ones. Gods (as differ-

entiated from nature deified) tend to

desire blood spilled by their

servants only under certain highly ritualized

circumstances, such as

sacrifices

and oath-swearings.

As a result, when

a cleric uses a forbid-

den weapon type

and hits he (she) becomes ritually polluted and loses

all ability to use

clerical skills and spells. Also, no experience

can be

gained (for clerical

purposes) while in a state of ritual pollution.

To be

cleansed, a pure cleric of at least level

x (6,7,8?) must perform a

ceremony involving holy water, incense

and costly material sacrifice. <atonement?>

Of course a cleric, polluted or not, always

fights on the clerical tables, no

matter what the weapon used.

Notes from a lesson at

the Grand Academy at Otheme, given by

Magister Scholae Wilibrod.

“You young cockerels have been talking

(Don’t deny it; I’ve got

Invisible Ears everywhere) about when

the going is touchy grabbing up

some glaive or man-splitter and hacking

about like some fool Warrior!

Idiots! Don’t you remember the Third Lesson?

More than a few ounces

of copper or iron close to you and your

spells get all turned about. And

each time you get all worked up and swing

something there is a one in

twenty chance adding up you’ll start forgetting

your spells! And the

psychic pollution takes a five-day fast!

And. . . .”

< remarks are unending-Novice Grimbolt >

Why can’t Magic

Users use arms, armor and weapons as well as

spells? They can! But above a certain

lower limit (eight ounces) any

copper or

iron

alloy that is within about two inches (52 mm) of the MU

has a tendency to foul up the spells that

are being cast (say, point of

origin detonation of fireballs).

For each ounce above the minimum

there should be about a 3% chance of a

malfunction in the spell. This

weight includes materials that are in

contact with the metal within the

critical limits. So a 2½ lb. sword

would have a 96% negative effect if

worn or used. And a 20 lb. chain shirt.

. .

If you remember that

spells have to be memorized and held in the

mind by an effort of will, it should be

apparent that the excitement of

melee might well weaken the grip of the

MU’s mind on the spells it

holds, the most complex (and potent) ones

first. This effect could be

simulated by a 5% chance per melee round

(cumulative per round) of

forgetting a spell. After each melee round

the MU is in combat, and DM

rolls (5% the first time, 10% the next)

to see if a spell is forgotten. Once

one is gone, then you start over again

with the next. When all the spells

on one level are gone, start on the next

lower. Determine which on

each level is forgotten either randomly,

or by DM’s whim.

OUT ON A LIMB

More swordplay

To the editor:

I read Lawrence Huss’s article in TD-33

concerning

rationales for forbidding clerics and

mages the use of the sword with both interest

and disappointment, for he left much unsaid on

the subject. To begin with, I think it would have

been more useful to begin with the real reason

why the D&D rules deny

swords to clerics and

mages, which is to take from them a certain

degree of combat effectiveness so that fighters

will be better at fighting than any other class.

This may seem elementary, but some of the

newer players may not realize it and lose track of

the important underlying reason for the rule.

Among the weapons in D&D, the sword does

more damage than any other, and it is for that

reason that most fighters use the sword. By providing

that the cleric is limited to blunt weapons,

the rules really mean that the cleric is limited to

weapons that do less damage. Similarly, the rule

limiting mages to the dagger as their weapon

was intended to limit them to a weapon that is

less powerful than not only the sword but the

mace as well. It is an interesting quirk of history

that under the Greyhawk

rules, the characteristic

weapon of these 3 classes does the same

damage as their own HD, but that is probably

coincidental.

The rationale given in the TD-33 article for

limiting clerics to club, mace, and flail, unfortunately,

does not hold together very well. The

excuse that a cleric must use stafflike weapons

because of their symbolic value makes little

sense, since if a mace or hammer is stafflike so is

an axe, while if a flail is stafflike so is a morningstar.

The argument is specious, particularly with

respect to the flail, of which there are many

varieties that are that are staffllike only in that they have a

staff as a handle, an argument that also applies to the spear.

More importantly, the fundamental basis of

the argument is that ‘God said to do it that way.’

But the appeal to a High Power that judges all

clerics suffers badly in logic in a world in which

the gods are real. In a polytheistic universe, it

begs the question to suggest that there might be,

after all, an all-powerful single godhead hiding

behind the multiplicity of apparent gods on

which you can peg a rationale for a rule.

Thus, the argument that a cleric becomes

spiritually polluted from using an edged or

pointed weapon in the sight of the cleric’s god

completely misses the point to the nature of

religion. If the gods are real, then a cleric will pay

close attention to his or her god’s or goddess’s

favorite weapon, on pain of offending the deity

in question, which can lead to harsh penalties.

The result is that while a priest of Thor

will naturally

use the hammer, a priest of Odin will

carry a

spear; a priest of Ares will choose

the sword,

while a priestess of Diana might specialize

in

archery; and so on. The entire concept

of a <link>

master power behind the gods doesn't make

sense in the D&D rules, which are premised on a

polytheistic universe.

The original clerics-and-maces arrangement

probably originated in the medieval Christian

clerical hypocrisy that a cleric could not represent

the Prince of Peaec while cutting people up

with a sword, but that clubbing them to death

was all right because it was less messy. Regardless

of the theological validity of this idea, it

simply doesn't apply to clerics of other gods,

however. This leaves us without a satisfactory

rationale for limiting cleics to blunt weapons, in

my opinion, other than a plea to a game balance

argument.

The rationale offered for mages being unable

to handle metal while casting spells has a

solid background in western fantasy tradition, at

least concerning the effect of cold iron on magic.

Unfortunately for the argument, there is no similar

tradition with respect to copper and copper

alloys (brass and bronze). What is there about

copper that interacts badly with magic, when

mages traditionally use brass implements? If

copper is harmful, why not gold? Silver? Mithril?

Remember that the latter two metals have a

tradition of not only not interfering with magic,

but they are also thought to contain or transmit

magic particularly well.

In addition, the metal-vs. -magic argument

fails to restrain mages from wearing non-metal

armor. Leather armor is an obvious suggestion

but armor made from laminated cloth was used

successfully by the Greeks, and would be attractive

to mages as a metal substitute. Furthermore,

there are lots of nonmetallic weapons that

mages could use, if metal is the only bar to

this—a stone club, for example. In fact, there is

an inconsistency in the rules that suggests a

mage can use a quarterstaff as a weapon, since

the Staff of Striking is a magical quarterstaff, and

there is no good reason why someone who can

use that cannot use a nonmagical staff as a

weapon.

The D&D rules specify a large number of

magical items that normally are made of metal

that could be a copper or iron alloy. Limiting

ourselves to the Greyhawk tables of items specifically

limited to or usable by mages, we find

Helms, Bottles, Tridents, Bracers, Gauntlets,

Bowls, Decanters, Beakers, and Braziers in profusion.

Potion bottles and scroll cases are often

made of brass, in one local campaign; braziers

are traditionally made of brass; tridents probably

are bronze; and so forth.

A more serious objection to the metal-vs.-

magic theory, however, is built into the D&D

rules structure: Clerics use magic while wearing

plate armor and carrying metal weapons. My

personal belief is that clerics get their spells exactly

the same way mages do, that in fact clerics

are a combined class of warriors who are also

specialty mages. The reason behind this statement

is that many of the spells usable by clerics

are ones they hold in common with other

mages —detects, light, hold person, protection

from evil, and others. I do not believe in the

theory that clerics get their magic directly from

their gods. In the first place, to refer to casting

Detect Magic as a “miracle” cheapens the concept

to trivia—a miracle is divine intervention,

and should be restricted to special cases. In the

second place, the multiplicity of gods makes the

standard list of clerical spells highly suspect in

terms of each god’s or goddess’s personal inclinations,

if that’s where they come from. The

same problem makes the idea that clerics get the

ability to throw magic while wearing metal

equally suspect; Athena approves of

armor but

Diana doesn’t. <link>

Magic is magic, it seems to me, whether cast

by a mage, cleric, druid, bard, or whatever. If

this is so, then clerics use the same mechanics in

using magic and are subject to the same restrictions

as mages. It is true that some spells operate

differently in the hands of clerics than in those of

mages, but this can be explained by clerics being

specialists who are better at what they get in their

restricted list of spells than generalist mages,

without appealing to divine intervention as an

excuse. I might note that this raises the question

of how druids throw spells if they must learn

them like anybody else (how does an illiterate

read a spellbook?), but this problem exists under

any interpretation of the rules because druids do

not have a personal god to appeal to, only nature.

But druids throw many of the same spells

that generalist mages use, while using swords.

As for the suggestion that mages who get into

melee will forget their spells, this is simple brutality

on the part of the GM. You don’t forget

things permanently while excited, or we would

all be leading monastic lives for fear of losing our

professional skills. This idea is no more than a

“do it my way or else” approach, and is no way

to retain the respect of your players. A gamebalance

argument, for all its limitations as a rationale,

is a better method than that.

John T. Sapienza, Jr.

Washington, D.C.

(Dragon #41)

'New freshmen'

To the Editor,

I am writing this letter to clear up some

problems that appear in my article in

the August

1979 issue of “The Dragon” A rather dull

part of

my article was edited out. While this

made the

article more readable, it created a small

problem

with my description of freshmen. In the

article, the

first paragraph states “. . .most . .

. of the returning

freshmen had heard of D&D.

However, none

of the new freshmen knew how to play.”

Before

my article was edited, it stated dryly

that all of the

returning freshmen who had gone to Cranbrook

in the eighth grade were “day” students

(not

those who flunked!). The “new freshmen”

of the

article are the boarders, none of whom

were at

Cranbrook in the eighth grade. Since the

boarders

had a lot of free time together, D&D

was the

perfect thing for them. So, there were

only four or

five freshmen boarders who did not play

D&D.

There were more than four freshmen “day”

students

who didn’t play D&D.

Whenever the article

says “new” freshmen it means freshmen

boarders.

Another thing that was edited was the names

of the DMs. They did a superb job and

deserve the

credit of being mentioned. They were:

David

Albrecht, David Baxter, Chuck Chung, John

Dennis, Paul Dworkin, Paul Gamble, Todd

Golding, Tod Leavitt, Robert Nederlander,

and

Marshal Eisenberg. The last thing about

the article

is about our club. We would appreciate

any assistance

or suggestions on club charter, constitution,

by-laws, etc. A copy of an existing club’s

rules

would be greatly appreciated.

Dan Bromberg—MI

(The Dragon #33)