-

-

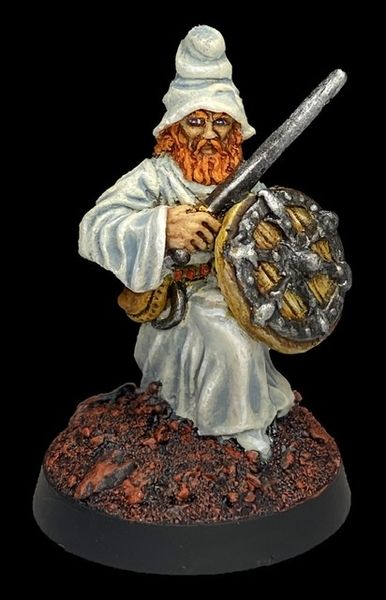

The Celtic world in the era of the Druid

Druids as we perceive them today are

really the romanticized version

of the priest/judge class of the ancient Celts. Ranking immediately

below the warrior aristocracy in prestige, the Druid was a vital and

influential part of the Celtic culture. The Romans, who were contemporary

with the peak of Druid power and development, commented

many times on their role in the Gaulish society. Posedonius stated

that

the Druids were “held in much honor” and Caesar in his Gaulish Wars

said that the Druids comprised one of the “two classes of men of some

dignity and importance.” Caesar later instituted a suppression of the

Druidic religion which virtually eliminated it as a force in the Gaulish

provinces. The suppression was most likely inspired more by the basically

nationalistic nature of the Druid’s political role than by religious

concerns.

THE CELTIC CULTURE

The culture of the Celts (and Druidism)

was widespread and relatively

homogeneous. Celtic tribes from the Bactrian Near East to Ireland

shared many similar traditions and beliefs. Originating in Central

and

West Central Europe, stylized art forms have been discovered in Celtic

colonies as far apart as Delphi, Iberia, Asia Minor and the Ukraine.

Iron

working was a developed industry among the Celts with some primitive

versions of carbon steel being used. The center of the iron industry

was

most likely near Paris, judging from the quantity of iron bars and

weapons found there.

A very active trade was carried out among the Celtic tribes. Goods

regularly seem to have traveled the width of Western Europe and gold

and silver coins were commonly used. Many of their trade routes were

followed by merchants centuries later.

Though viewed as culturally inferior (as was everyone else) by the

early Greeks and Egyptians, Celtic mercenaries were commonly used

by the civilized Mediterranean cultures. Tribes of Celts served with

the

Greeks in Sicily in 368 BC and with the Egyptians as late as 274 BC.

Their first appearance is lost in obscurity.

The Celtic culture was “prehistoric” in that writing and literacy were

virtually nonexistent. The Celts never did develop a written language

that was universally used. Later the written languages of nearby cultures

were adopted, particularly Latin after Caesar’s conquests. Therefore,

the tradition of Druidism was entirely oral. Poetry and memorization

played an important part in Druidic education. This is reflected by

the

inability of a Druid to use any written magical items. Presumably this

includes all tomes, scrolls, and similar types of paraphernalia. Logically,

even maps or road signs would be unintelligible to a classic Druid,

who

would most likely have the terrain memorized so well as to not need

such aids anyhow.

BARDS AND SEERS

Because of this lack of literacy, a subgroup of the Druids arose within

the Celtic culture. These are the Bardoi. Separate

from the priestlike

Druids, the Bards were actually a distinct subgroup of the Druids and

received many of the same immunities and privileges. The Celtic bard

was a historian and entertainer, as described in the Player’s Guide.

The

Celtic culture was a Warrior/Heroic culture where personal valor and

feats of arms were a key to status. In such a culture it was a necessity

to

have a group that could spread the tales of your courage or abilities.

This

was the role of the Bard. Throughout the history of Druidism, it was

extremely rare for a Druid to act in any way like a Bard, even the

use of

rhymes in public.

A third, less distinct subgroup of the Druids is also commonly found

in the literature of their contemporaries. These were the Abioi (or

Vates

or Ouaties) or Seers. This group would study natural phenomena and

the movements of sacrifices. From these they attempted to predict the

future. Though Seers were also originally a distinct group, even before

the Roman conquest of Gaul several references can be found to the

Druids themselves performing this function. Eventually this was done

by

the Druids of Ireland, even as late as the 11th century.

GROVES AND TEMPLES

If a description of the Celtic

culture has begun to bring forth pictures <Celtic

= Irish?>

of early medieval Europe, it is not surprising The resemblances between

the two cultures are numerous. Both were very strongly based in

agriculture. Crops and farming techniques differed little. Some horses

were raised along with other herd animals, but these were usually the

size of ponies; most would stand 10 to 11 hands high at best. This

is

hardly a suitable mount for cavalry, at least shock cavalry. As such,

the

Celtic warrior or Druid traveled and fought primarily on foot.

The Celts did use a sort of chariot, often an open, solid-wheeled

platform. This is thought to have been derived from Oriental influences.

In the early periods of the culture, the chariot was an integral part

of

Celtic tactics. Their use is described in accounts of the Battle of

Sentinum

(295 BC) and a few were used by the Averni as late as 121 BC. By the

time of Caesar, their use had disappeared from the continent, although

the chariot was retained in Britain and Ireland for several more centuries,

to lessening degrees.

Perhaps the widespread forests that covered much of the Celtic

lands limited the tactical advantages of the chariots. These same forests

gave rise to a large number of timber-based industries. These deep,

and—to the Romans, from whom we have most of our informationominous

forests. (Hades was surrounded by a dark forest) were a basic

factor in the Celtic culture. From Roman writings has been passed down

the importance of oak and mistletoe. Since it was one of the basic

parts

of the economy in their culture, it is not surprising that the forest

itself

and the powers behind it took a primary role in the Druidic religion.

The Celtic culture of the Druid was not a peaceful world. Warfare

was a constant fact of life for the Celtic tribes. Wars on all levels

were

common, especially petty warfare between tribes or families. Simply

put, in a warrior culture it was necessary to have wars in order to

provide

a means for the warriors to practice their trade and achieve distinction.

Reflecting this is the large number of fortifications which have been

uncovered from this period. Most of these are earthworks of varying

sizes on hilltops or in the centers of large plains.

The weaponry of the Celts would be familiar to any D&D player in

that they favored the sword, spear, and shield. Armor was uncommon,

as were helmets. Again, this may reflect the emphasis on individual

courage and heroism in their culture. The Celtic warrior fought with

his

fellow tribesmen and allies. The occasional outstanding leader could

convince several tribes to cooperate, such as Vertogorex did against

Julius Caesar. Celtic tactics were to rush forward frontally and overwhelm

the enemy, with little in the way of formation.

With this large number of antagonistic tribes (Ptolemy lists 33 major

tribes in Britain; one in Ulster contained 35 smaller tribes), the

Druids

were the force that united the culture.

THE ROLE OF THE DRUID

Perhaps the most important role that the Druid

played was as a

mediator of disputes. Strabo stated that the Druids were able “to restrain

the hands of their fellows.” Diodorus, a few centuries later, stated

more

broadly, “thus even among the most savage barbarians,

anger yields to

wisdom.” The Druid was the peacemaker who could intervene in any

armed dispute. Because of this and the Druid’s role as the judge in

civil

matters, the person of the Druid was inviolate to all Celts. He was

not to

be interfered with or harmed by any man. To do so was to be cursed

and

an outcast from all the tribes.

In return for their special status and protections, Druids were asked

to hold themselves above all partisan activities. A Druid was ideally

totally neutral in all disputes and wise enough to judge all cases

on their

merit alone. To vary from this was to cease to function as a Druid

in one

of his most vital roles, a role that was needed to keep the Celtic

culture

from fragmenting from its own internal pressures. (Some additional

spells and abilities are suggested later to reflect the “peacemaker”

aspect of Druidism.)

During the more recent centuries, the Irish Druid varied greatly from

his earlier namesake. Referred to often as the Aes dana (men of special

gifts), the Druid in Ireland eventually became a partisan member of

a

tribe or group. Also, the role of seer was often expected of the Irish

Druid

in later centuries. There are even some Irish ballads that tell of

a Druid

joining others to shame a hero into joining a battle. Conchoban, a

famed

chieftain in Ulster, was the son of Cathbad, a renowned Druid who had

himself led a warrior band in his youth. With only these later exceptions,

however, the role of the Celtic Druid was that of neutral arbitrator.

THE DRUID AS TEACHER

The Druid was basically then only “educated” class in the Celtic

culture. They often served as teachers to the youth of the aristocracy.

Great prestige was available to a noble whose sons were instructed

by a

well-known Druid. this role as teacher-especially as itinerant teacher—

also helped to link together the Celtic society. It is not unreasonable

to introduce into your campaign the fact that a Druid would be fed,

housed, and even rewarded by a noble in exchange for instructing his

children. This could be easily treated in the same manner as you treat

the exchange of their subgroup, the Bard, of songs for hospitality.

As per

tradition, much of this teaching was done in sacred caves or in clearings

in the everpresent deciduous oak forest.

TEMPLES AND GROVES

There are, surprisingly, virtually no ancient references to Sacred

Groves as places of worship. It is possible that part of this tradition

is

based upon the use of clearings for the teachings discussed above.

Impetus may have been added by Caesar’s reference to a great annual

assembly in a “Sacred Place” in the territory of the Camutes. possibly

near Milan. Most references to a “Sacred Grove” are found in literature

dating from the 18th century and later. There was during this period

a

definite effort in Britain, spurred undoubtedly by the nationalism

of the

British Empire, to show that the British Druid was actually a direct

descendant of Noah. This led to a correlation between the Druid’s

groves and those described in the Old Testament as used by the Jewish

patriarchs. The image caught the public’s fancy and has been an integral

part of the Druidic myth ever since.

Distribution of Romano-Celtic Temples

Actually, the remains of numerous temples have been found

throughout the areas dominated by the Celts. Generally these were

made of timber and were square or rectangular in shape. Most consisted

of an outer wall and a central building (see diagram). Often a larger

earthworks surrounded the entire area and possibly some nearby dwellings.

Several graves, possibly of the priests, have been found within the

temple grounds. Both men and women did serve as Druids,

and one of

the richest graves yet found is that of a female who is speculated

to have

been the priestess of the temple.

Plan of timber built temple at Heath Row, Middlesex

THE RELIGION OF THE DRUID

The origin of the word “Druid” is

not clear. It is possibly the Latin

(Druidae) translation of the Gaulish Druvis or Druvids. The actual

term

was most likely coined by Greek or Roman authors. “Drus” is Greek for

oak tree and “Vid” is the Indo-European phrase “to know.” It would

be

an appropriate derivation for a religion based in the deciduous forests

of

Central Europe.

The Druids actually seemed to have a pantheistic religion. There

were many gods, many of whom were undoubtedly based in the Nature

that surrounded the people and upon which they were so dependent. It

seems likely from the variation of the wooden votive images found that

there was a tendency for some cults to become quite dominant in an

area. Again, it is from the 18th-century idealized view of the Druid

as a

“pure primitive” being closer to the Natural Truths that we get much

of

our view of the Druid as being concerned primarily with the things

of the

woodland. It is likely that many Druids were quite knowledgeable in

the

area, but little of the literature about them even refers to that knowledge,

until their renewed popularity in Britain. It is perhaps more valid

to

speculate that the Druid would be just as concerned with agriculture.

The Druidic religion had its darker aspects also. References to these

are common in contemporary literature of Rome, but have tended to be

glossed over when the later, romanticized Druid was discussed. Human

sacrifice was evidently not uncommon in the practices of the Druids.

Several of their religious decorations feature the image of a giant

god

drowning a victim in a sacred cauldron. Cimbri, a Celtic chief, is

reported

to have sent to Augustus Caesar “the most sacred cauldron in

their country” as a diplomatic gift, sacred cauldrons of iron being

a

common part of Druidic ceremonies. Strabo, recording the event, then

goes on to explain that the cauldron was used to sacrifice prisoners

of

war by having their throats slit over it. The human skull is often

found

among the votive gifts in temple sites. One dominant cult in Gaul is,

in

fact, referred to as the “cult of the severed head” in reference to

the

main item used in decorating the walls of their temples and forts.

The fact that the Druids buried their dead with useful utensils and

weapons substantiates the statements that the Druids believed in an

afterlife. It was, it seems, common for a Celtic chief to have burned

with

him virtually all of his possessions. Julius Caesar describes the funeral

of

a Celtic noble as being “splendid and costly” in view of the standard

of

living.

There are many references to the use of the symbols of the forest in

the Druidic religion. Oak and mistletoe are a recurring theme. Druidic

temples were almost always wooden and their images carved from

hardwoods. The favorite magic referred to is the ability of the Druid

to

curse those who defy his decisions (most likely a banning rather than

a

spiritual curse). As the major center of literacy, the Druid was also

the

expert in medicine, especially in the use of herbs. Pliny gives us

several

accounts of “charms” the Druids wrought using herbs, mistletoe, and,

in one case, sea urchins.

The Druids were a class of well respected, protected, and learned

men who served a vital role in Celtic society. Together with the Bards

and Seers, they formed the priesthood and literate class of the Celts

for

the entire history of the culture. The Druid himself served many related

functions. In times of war, or in armed disputes, the Druid was a

mediator. In peacetime the Druid was the civil judge, educator, and

source of needed knowledge in matters of all types. Always, the Druid

was the priest of the Celtic culture.

DECLARATION OF PEACE

A new Druidic ability

Although the Druid, due to his involvement with life, is unable to

turn undead, his role of the peacemaker gives him a similar ability

with

most humanoids. Before or during any armed combat

if he has not

struck any blow, a Druid has the ability to make a Declaration of Peace.

This declaration has a 10% plus 5% per level (15% 1st level, 20% 2nd,

etc.) chance of causing all armed combat to cease for two rounds per

level of the Druid. This does not affect magical combat in any way,

nor

will it stop a humanoid who is in combat with any non-humanoid

opponent. Once the combat is stopped, any non-combat activities may

take place such as cures, running away (and chasing), blesses, magic

of

any form, or even trying to talk out the dispute.

After peace has been successfully Declared, combat will resume

when the effect wears off (roll initiatives), or at any time earlier

if anyone

who is under the restraint of the Declaration is physically harmed

in any

way. This could be caused by an outside party or even by magic, which

is not restrained by the Declaration. A fireball going off tends to

destroy

even a temporary mood of reconciliation. Once a Druid strikes a blow

or

causes direct harm in any way to a member of a party of humanoids,

he

permanently loses his ability to include any member of that party in

a

Declaration of Peace. The Declaration of Peace affects all those within

the sound of the Druid’s voice, a 50’ radius which may be modified

by

circumstances.

DRUIDIC MAGIC ITEMS

The cauldron played a large part in Druidic ceremonies. Below are

listed several types of cauldrons that might be used by a Druid.

All are

usable only by them. Cauldrons are made of iron, 1 to 1½ feet

in

diameter, and rather heavy.

Cauldron of Warming: This cauldron has the effect of being able

to

warm any liquid placed in it to its boiling point without the aid of

a fire or

other outside heat.

Cauldron of Foretelling: The possessor

of this cauldron can cast one

extra augury spell per day by concentrating

on the swirling of mistletoe

in the water within it. The augury takes effect as the water is magically

heated.

Cauldron of Healing: Once per week this cauldron will turn a

mixture of crushed pearl (100 gp worth), mistletoe, and wine into a

potion that will heal 1-4 points of damage.

Cauldron of Restoring Freshness: Any herb left in this cauldron

overnight and sprinkled with salt,

sugar, and ground pearl (100 gp) will

be restored to the condition it was in one day after being picked.

This will

not restore any herb that was consumed or turned to dust.

Cauldron of Fresh Water: This cauldron

fills three times per day with

pure water.

Cauldron of Ambrosia: Once per week this cauldron produces one

gallon of a golden wine with an exquisite

taste. This may be sold for a

minimum of 50 gp or has a 50% chance of distracting any nonintelligent

monster, if splashed before him, with its tantalizing odor. This

wine sours to vinegar in one week.

Cauldron of Blindness:

This cauldron taints any edible placed within

it so that when it is consumed or rubbed over the body, blindness for

1-3

days ensues. It is otherwise indetectable from a Cauldron of Warming

or a Cauldron of Restoring Freshness.

Cauldron of Entrancement: This cauldron appears to be a cauldron

of Foretelling, but any Druid using it is

entranced by it and cannot tear

his eyes away (as a charm). If he is physically removed from this

cauldron, the shock will render the Druid unconscious for 1-4 hours.

Cauldron of Creatures: Once per week this cauldron allows a Druid

to become polymorphed into any natural animal, bird, or reptile. This

is

done by sprinkling into fresh water

a powder made of crushed ruby

(500 gp minimum value), mistletoe, mandrake, and some part of the

creature desired. The polymorph will last for up to one week, but can

be

ended at any time by the Druid who is changed. Treat otherwise as a

Polymorph Self, but the Druid is only rendered unconscious if he fails

system shock.

Cauldron of the Arch Druid:

Traditionally the possession of the Arch

Druid, this cauldron has the powers of all the cauldrons listed above.

Each power may be used once per week. Druids lower than 10th level

have a 50% chance of not getting the power desired. (Roll a 10-sided

die for the effect. On a roll of ten the cauldron cracks and is useless.)

HERBS

The Druid was, as mentioned, an expert in herbs

and their use.

During the Middle Ages, dozens of herbs were said to have had magical

powers. A majority of the herbs listed below should be comparatively

rare and difficult to find. Due to their usefulness, they will never

be found

growing near areas of human habitation or along roads or other places

where easily found. A Druid should probably need to make a special

effort to seek out these plants in remote forests and clearings. Even

then,

potent herbs would be hard to find. Possibly a 3% per level likelihood

of

discovering and recognizing any one herb, with the probability doubled

if only one particular herb is being sought, would give the appropriate

level of difficulty.

The herbs of the Middle Ages were divided into those used for Black

Magic and those used for White or Protective Magic. Listed below are

several examples of both types. Listed with each herb’s common name

is its botanical or Latin name to assist those who wish to do further

research into their “powers.” In nearly all cases the usefulness of

the

herb is limited in duration. Once the leaf, root or whatever has wilted

or

dried, its effect should either disappear or be greatly diminished.

Black Magical Herbs

Satan’s Feces (Ferula

Assafoetida): The roots of this very rare herb

act when eaten to give the user protection from

any devil (not demon)

summoned by him in the same manner as a pentagram.

The duration is

limited (1-8 turns) and varies with the freshness

and potency of the root.

Devil’s Hand (Orchid Gymnadenai): The orchid has

often been

associated with Satan

in mythology and you may wish to include several

types of the beautiful, but foul-smelling, flower

in your campaign. If

struck with the blossom of this plant while being

cursed, a character will

have 3 subtracted from his saving throw.

Mandrake (Mandragora Officinarum): The mythology

of the Mandrake

could be an article in itself. Suggested here

are two of the more

common powers attributed to the herb. The fruit

of the Mandrake is

called the “devil’s testicles” and is used in

ceremonies relating to fertility.

This plant is greatly treasured by evil Magic

Users, as it is needed in the

creation of orcs

and greatly increases the fecundity of any goblin-class

monster. The root of the Mandrake has been granted

by myth to have

healing abilities (and so should really be considered

white magic).

Consuming the root will cure 8 points of damage,

minus one for every

day since the root was picked.

Giant Puffball (Calvatia Gigantia): This large

fungus can be up to 1’

across. When burst with the proper incantation,

it will act as dust of

sneezing and weeping for a 10’ x 10’ area. It

is rather FRAGILE and will

burst with any hard blow.

Black Hellbore (Hellboris Niger): This was attributed

by the French

to cause witches to become

invisible and so be able to fly undetected.

The dust from three roots of this herb will cause

whom or whatever it is

sprinkled over to become invisible for 3-8 turns.

If the dust is washed or

blown away, the wearer becomes visible. This

herb does not lose its

potency over time and so can be accumulated.

Linden Tree Leaves (Tilia Vulgare): When crushed

into wine, they

are said to give the drinker a glimpse of the

future. Treat as a very limited

augury spell.

A side effect is that it causes the user to also become very

drunk immediately after the augury.

The Centaury (Esythraeci Centarium): A love philter.

Moonwort leaves (Botrychium Lunaria or Lunaria

Annua): They

cause any horse

that trods on them to go lame.

Sweet Basil (Ocimium Basilicurn): When mixed with

horse dung, it

will produce a scorpion of normal size, but of

double potency, as related

in the 17th century Decameron.

White Magical Herbs

Mistletoe

is vital to Druidic spells and is treated fully in the Player’s

Guide.

Benedicta (Geum Uranum) protects against venoms

when worn

around the neck; add +2 to all saving

throws. The effect lessens two

weeks after picking.

A sprig of Rue (Rata Graveolens), when dipped in holy

water and

rubbed on the body, will add +1 to saving throws

against evil creatures.

This effect uses up the sprig and lasts for four

hours.

The Sacred Herb (Verbena Officinalis) was actually

used by the

Druids in their “lustral water.”

When drunk with wine, it causes +2

strength and uncontrollable lust for 3-8 turns.

The Hypersicum (over the phantom in Greek) is

an herb that adds

+l to any cleric’s die roll for turning

undead. The herb must be

consumed in the round immediately before the

Turn is attempted and

the effect lasts for only the round after consumption.

Charlemagne’s Herb (Carolus Magnus) was said to

have been given

to Charlemagne when his army was struck by a

plague. This very rare

herb cures

any disease if consumed within three days of being picked.

Lycopodium is said to have been used by Druidic

nuns on the of

Sain in the Loire valley. It was picked with

a very complicated ritual

(25% chance minus 2% per level of error) and

was said to bring good

luck. Treat as a +1 luckstone for 30 days after

picking.

The root of the Peony (Paeonia Qfficinalis) or

the paeonia to the

Greeks, was felt to have been blessed by Paeon,

the giver of light, with

the ability to protect the wearer against magic.

The dried root worn in a

pouch on a leather thong around the neck will

add +2 to one saving

throw against magic and then turn to useless

dust. If worn, it will react to

the first spell thrown at the user.

Springwort or Blasting Root (Euphorbia), if eaten

by a thief immediately

before an attempt is made to open a lock, will

add 10% to the

thief 's likelihood of success. The root loses

1% of this effect for every

week since it has been dug up to a minimum of

5%. The entire root must

be eaten, and the effect of several roots would

be non-cumulative.

Scarlet Pimpernel (Anagallis Arvensis) is said

to have sprung from

Christ’s blood at Calvary. It was thought to

be a potent cure for the

magic of witches. The

leaves when eaten act as a dispel magic spell

equal in level to the level of the Druid who

picked the plant. After 30

days this ability is lost and the leaves become

a mild narcotic causing the

user to sleep for 1-4 hours.

Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) was said to protect

against “flying evil

things.” If a fresh sprig of the plant is carried

so as to be visible from

above, the wearer will be undetectable by any

evil creature that is in

flight unless the monster saves

versus spells at -3. If the creature does

save, it will be attracted to the wearer before

all ordinary party members.

Coco de mer (the seed of the Lodocea) was thought to be a

preventative for poisons.

If a poison is drunk from a cup made from the

very large seed, it will have no effect. Needless

to say, this seed is very

rare and highly prized by kings, lords, and others

who might be the

object of assassination attempts. The cup keeps

its potency for 1 year.

You will probably wish to add your own herbs

to this list. Many

drugs we are familiar with today, legal and illegal,

are the products of

herbs. You may even wish to add some of your

own inventions that

have beneficial effects and annoying side effects.