| Combat Computer | Landragons | Electrum dragon | Seven swords | Bulette: Ecology |

| The vicarious participator | A PC and His Money . . . | Warhorses & Barding | LTH: Bureaucrats & Politicians | Dragon |

'Male oriented'

Dear Editor:

I am a new subscriber to your fine publica-

tion and would like to commend you on

a job

well done. However (isn?t there always

a how-

ever?), I am quite bothered by the very

male

oriented nature of your writing and illustra-

tions. I realize that most of your readers

and,

indeed, most gamers are male. But I fail

to see

how you plan on gaining any female players

and readers by the continual ignoring

of them.

In defense of my point: issue #72. Yes,

there

are two female warriors on the cover and

a

drawing of a female cavalier. But so what?

Throughout the rest of the magazine we

see all

male warriors and jesters, hunters and

magic

users. To top it off, Roger E. Moore's

story

is

wholly from the male perspective. Are

there

only succubi? Where are the incubi? Surely

you

know that this fiend has no true gender

but

rather appears in the image of the desired

crea-

ture for the victim.

Theresa A. Reed

Portland, Ore.

Yes, the cover of issue #72 pictured

two

female warriors. In fact, seven of

the last 10

covers we've published (not counting

this

magazine) have included a female character.

I

won?t count the number of times we've

por-

trayed females in artwork on the inside

pages

during those 10 issues -- but I will

point out

that issue #72 has a picture of a female

barbar-

ian (on page 27), in addition to the

female

cavalier (on page 10) that Theresa

mentions.

As for Roger Moore, I don't think he?ll

mind

me pointing out that he writes ?from

the male

perspective? because he is

a male. If he tried to

write from a female perspective or

from a dual

perspective ? especially for a story

about ?sex

in the AD&D?

world? ? he?d be even crazier

than he is already. And where are the

incubi?

Well, to be technical about it, they're

not in

the "AD&D

world" (the succubus is listed in

the Monster Manual, but not

the incubus), and

therefore incubi were not within the

?terri-

tory? covered by the

article. And, heck, the

whole thing was for a laugh anyway,

right?

I don?t mean to sound flippant. I think

we?ve done okay when it comes to representing

the roles of both sexes in the realm

of role-

playing games, and we?ll continue to

try to

look at the ?female perspective? whenever

we

can. Like it says in the response to

the letter on

page 3, we really do want to try to

make eve-

ryone happy. If you agree with Theresa?s

point

of view, please let us know, and (I

know this

sounds high-falutin? ? but it?s true

anyway)

you can play a part in shaping the

future of

this magazine. ?KM

Obviously, not all creatures wear armor with

set AC values, but instead they depend on their

natural armor and/or dexterity. The article states,

"regardless of the actual AC a piece of equipment

provides its wearer, the apparent AC of that

armor is the same for all armor of that type."

This presents problems.

Suppose I wish to handle melee between a

group of adventurers and a xorn. The xorn wears

no armor, is not too quick on its feet, and (to the

best of my knowledge) doesn't improve its AC

value through any magical means. Thus its AC

value of -2 must be enhanced by its natural stonelike

shell. What is the apparent AC of stone-mail?

The same goes for the apparent AC of, say,

Asmodeus. To the best of my knowledge he does

not wear any armor. Since his AC of -7 is obviously

enhanced by some means, what would his

apparent AC be -- 10? That can't be right.

This is mostly a minor complaint (since I?m

sure there are many DMs out there who disregard

AC adjustments altogether) but if there is

any reasonable answer to this dilemma, I would

be happy to hear it.

Rob Paige

Cheney, Wash.

(Dragon #82)

We checked out this question with Tracy Hickman,

who is on the TSR design staff was the

creator of the Combat Computer. He told us

what we expected to hear -- namely, that no

provision exists in the AD&D rules

for taking

AC adjustments in to consideration in cases like

the ones Rob describes, which is why the Combat

Computer didn't address the question.

The problem can?t really be solved (short of an

official addition to the rules), but it can be handled

in one of two ways:

(a) Don't use any armor class adjustment for

weapon type against creatures with an AC of

better than 2, when that armor class can't be

equated to an "apparent" AC, or

(b) Treat any "problem" AC as if the creature

in question had an actual armor class of 2, which

is as low as the armor class adjustment table in

the Players Handbook goes.

<UA: the

AC adjustment table goes down to 0>

-- KM

(Dragon #82)

THE FORUM

In reference to Theresa Reed's

letter

about male orientation published

in issue

#74 of your magazine, I

would like to say

that I find your articles

are in general very

good, but there are occasions

when they are

downright terrible. In the

much maligned

issue #72, for instance,

there is an article

called "A

new name? It's elementary!"

Quite handy to have for

naming characters,

but what if those characters

are female? I

see in this article a word

for ?

"prince," but I

see no sign of a word for

?princess.? Simi-

larly, there are words for

?man,? ?god,?

and ?warrior, man? but the

female equiva-

lents are not even mentioned.

This oversight was bad enough,

but the

article about the new Duelist

NPC class in

the next issue of DRAGON

Magazine (#73)

was even worse. In this

article the Fenc-

ingmaster?s school is described

as a ?male

gossip shop? and there is

no hint whatso-

ever of the female pronoun

throughout the

entire article. It is true

that the profession

on which the Duelist NPC

class is based

was entirely made up of

males, but that is

no reason for it to be limited

in the AD&D

world. After all, fighters,

cavaliers, and

most thieves were male,

but Gary Gygax

has had the good sense not

to restrict the

game in that area, and in

so doing has

attracted many women to

the game. (No

doubt many men find the

?him/her,? ?he/

she? approach of Mr. Gygax?s

writing

cumbersome, but women resent

being

referred to as ?he,? just

as most men would

resent being referred to

as ?she.?)

There are a few other examples

I could

give of this male orientation,

but as they are

relatively minor I won?t

cloud over the

major issue by getting picky.

I would like to

emphasize, however, that

I do not want

articles written from the

female perspective.

They are just as bad as

articles written from

the male perspective, as

they too alienate a

large proportion of the

readership. What I

do want is for all articles

to be written from,

an unbiased perspective.

Elizabeth Perry

Wellington, New Zealand

P.S. Sorry this letter came

so late after the

subject of male orientation

was raised, but

issue #74 only arrived in

this remote part of

the prime material plane

three weeks ago.

Many moons ago (in DRAGON

issue #74)

Theresa Reed wrote a letter

to the editor stating

that she felt that DRAGON

Magazine was

?ignoring? women. I have

played AD&D

for two years and read the

magazine for

nearly as long,

and I do not feel that AD&D

is a ?male-oriented? game,

nor is

DRAGON a ?male-oriented?

magazine.

For example, in the Players

Handbook,

most of the entries that

can refer to

either male or female characters

are stated

as ?his or her.? I also

think that a slight

strength penalty for female

characters is not

sexist; it is actually rather

generous, if you

consider that the AD&D

game is based on a

medieval society, in which

women were

rarely allowed out of the

house! Compare

this to a game like the

one described in the

book Fantasy

Wargaming, in which female

player characters suffer

penalties such as -2

to charisma and -3 to social

class!

I must also commend DRAGON

Maga-

zine for its fairness. The

women we fre-

quently see on the covers

of the magazine

have been anything but weak

and helpless,

and are certainly clad in

more than chain-

mail bikinis. I can even

remember that one

old issue of DRAGON

contained an article <find this article>

which strongly discouraged

the use of rape

and pregnancy in campaigns.

Laurel Golding

Grosse Ile, Mich.

(Dragon #82)

Q: Is the 'Combat

Computer' in issue #74

designed for actual use

in AD&D gaming?

A: Yes.

It has been playtested,

and from

the mail readers have sent

to DRAGON

magazine, it appears to

be working very

well in AD&D

games.

(79.14)

One to a customer

Dear Editor:

I'm writing about the Combat

Computer

that appeared in issue #73.

I found that it <#74>

worked quite well.

I would like to know how I

could get another for my

group without having

to buy another magazine.

Robbie Dean

Mt. Carmel, Term.

We're glad the Combat

Computer got such a

good reception. Unfortunately,

we can't make

it available separately

from the magazine. We

assume that in a gaming

group of any substantial

size (say, more than

three people), it's

likely that more than

one of those group

members buys DRAGON®

Magazine, so "the

group" probably has no

trouble obtaining

more than one copy of

a certain article or a

special inclusion. If

you're a DM who insists

that your players not

be allowed to see what's

in the magazine (and

your players are willing

to go along with that

condition), THEN you

won't be able to obtain

multiple copies of

something we print without

buying multiple

copies of the magazine

it appeared in.

-- KM

(Dragon

#79)

A player character and his money.

. .

by Lewis Pulsipher

It has frequently been noted

that in

some FRPGs the

amount of money available

to, and actually

possessed by, PCs is

unbelievably enormous --

impossible to

transport, or to store in

anything smaller

than a castle.

Even a relatively inexperienced

character can, after not

too long,

afford almost anything he

can carry, and

such things as towers and

ships are

within the range of a character?s

pocketbook

before not too much longer

than

that.

Some gamemasters go to great

lengths

to describe goods and services

in their

campaigns in terms of their

?real? (that

is, medieval) prices ? very

low rates to

someone with several pounds

of gold

coins. Typically, suggestions

for the

?toning down? of a game's

monetary system

are met with two retorts:

first, it is a

"fact" of the

campaign that the area frequented

by adventurers is experiencing

rampant inflation; and second,

that this

is an adventure game, after

all, and huge

piles of gold are part of

the heroic milieu.

This article approaches

the subject of

money from two angles --

first, suggesting

a means of simplifying monetary

transactions while making

treasures more

believable and easier to

store or carry; and

second, describing some

ways in which a

referee can coax treasure

away from

adventurers once they've

discovered it.

The silver

standard

The

first part is easy. In any description

of

a hoard of monetary treasure,

replace

the word 'gold'

with 'silver.'

(But

don't change prices or values given

for

goods or services.) Adopt the "silver

standard"

which actually prevailed in late

medieval

times. A gold piece (arbitrarily

set

equal to 10 silver pieces to make calculations

easy)

becomes really valuable. And

silver,

once sneered at as "too cheap to

carry,"

takes its rightful place as the

wealthy

man's mode of exchange. Maintaining

the

proportion between gold

and

silver,

the value of a silver piece is set

equivalent

to 10 copper pieces.

The

copper

piece is small change, certainly,

but

not such a miniscule piece of currency

as

it is in some games.

In

a world where silver 'replaces' gold,

medieval

prices for ordinary goods and

services

are reasonable, and the net result

is

either unchanged or decreased spending

power

for adventurers.

Concerning

the size and weight problem,

a

display of medieval coins in a

museum

will show that coins minted

prior

to the modern era were very small,

rather

like an American dime or British

half-penny

(new pence). Consequently, in

bygone

days it was possible to carry a

small

fortune without risking a permanent

back

problem from the weight. Try

setting

the size and weight of a coin

(copper,

silver, or gold) equal to the size

and

weight of a dime. When this standard

is

used instead of, for instance, the

AD&D

game standard (where coins

weigh

a tenth of a pound each), someone

who

could carry a sack of 300 gold pieces

(30

pounds) in the old system can carry

6,584

gold in the new system (1 dime = 35

grains,

or 219+ coins/pound). And gold is

far

more valuable per piece, because the

silver

standard is used. (And this system

for

size and weight can only be used if the

silver

standard is also employed.)

Now,

personal fortunes are no longer

impossible

to carry, and adventurers don?t

need

magic bags or mules in order to

carry

a decent sum away from an adventure

(or

a theft).

Q:

In "A Player Character and His

Money"

(issue #74), are PCs supposed to

get

one experience point per silver piece

or

one x.p. per gold piece?

A:

Characters get one x.p. per gold piece.

The

'silver standard' described in the

article

will make it more difficult for

characters

to buy very valuable items

(especially

magical ones), but this contributes

to

game balance.

(79.14)

The origin

of treasures

Why, since gold

circulated so freely in

the ancient world, did it

virtually disappear

in the

Dark Ages? Much was

hoarded (e.g., buried) and

lost. Some was

successfully hoarded for

centuries. Most

of the remainder flowed

to the eastern

world

via trade. For a time, even silver

was so rare that most transactions

were by

barter rather than purchase.

In a sense,

adventurers are discovering

lost hoards

when they take treasure

from monsters. If

the history of your fantasy

world is like

that of Earth, having a

Dark Age or Age

of Chaos, there may justifiably

be a severe

shortage of gold (hence

its great value) in

the years that follow this

period. Most

personal wealth will be

in goods, not

money, and consequently

it will be relatively

difficult for a thief to

transport or

dispose of his gains. Except

through barter,

one can't "spend" a fur

coat || obsidian

necklace. Unless player

characters are

astute, they may sell such

"liberated"

items for far less than

their nominal

worth.

A player

character and his money . . .

What means are available

in the campaign

to separate player characters

from

the treasure which, sooner

or later, they

will accumulate? A few games

provide a

formal system for forcing

expenditures.

In the Runequest® game,

characters

spend money for training

and learning

spells. (Why they don?t

teach each other

for free I am unsure.) In

the AD&D game,

characters are supposed

to spend money

for training when they rise

a level. This

system seems unusable at

low levels,

where a character must spend

half his

time adventuring without

gaining experience

just to gain sufficient

funds to

reach the next level. So

what do you do if

your game has no such system,

or you

don?t like the one provided?

Here are

some possibilities:

Theft:

The obvious way to relieve characters

of their burden of wealth

is to

simply steal it (rather,

have it stolen), but

this can create tensions

outside the game.

If players aren't used to

losing money to

unseen and undetected thieves,

they're

going to be very unhappy,

and may think

the referee is unfair. In

other cases, players

won't mind theft so much,

provided

that 1) they have a chance

to catch the

thief and 2) their precautions

against

theft reduce the frequency

and success

rate of such attempts.

To illustrate the first

point: If the referee

simply says one day, "You

can't find

your money pouch," the player

will have

virtually no chance to stop

or catch the

thief. If, however, during

the course of

discussions at an inn or

on the street, the

referee casually refers

to someone bumping

into or jostling the character,

the

player has a chance to react

to the theft (if

he thinks about the possibility).

Or if a

theft occurs while the character

is sleeping,

he may be able to find some

clues to

help track down the miscreant.

As for the second point,

precautions: A

character who conceals rather

than

flaunts his wealth should

be less vulnerable

to theft than one who becomes

known

as a big spender. Furthermore,

some

players make lists of precautions

to be

observed by characters when

in towns or

other areas frequented by

thieves, while

others take no precautions.

The latter are

more likely to be successfully

robbed.

A character can be conned

out of his

money -- for example, when

he buys a

magic spell scroll which

turns out to have

flaws -- but frequent con

games and similar

forms of deceit are no fun

for referee

or players. Moreover, players

soon

become extremely wary, making

it almost

impossible to "fairly" con

them. But

most important, con games,

moreso than

ordinary theft, are too

personal. This feels

too much like the referee,

rather than the

monsters and NPCs, against

the players,

obstructing the ideal of

the referee as an

impartial arbiter. For this

reason alone,

deceit is not a satisfactory

way to relieve

characters of their treasure.

Players soon become so wary

of ordinary

theft that the referee cannot

successfully

steal large sums without

resorting to

strongarm tactics -- for

example, an

extortioner who happens

to be a highlevel

assassin. Once again, this

results in

an adversary relationship

likely to sour

the game, if not personal

relations outside

of it. Theft is not enough.

Upkeep:

Since adventurers spend only

a small part of their time

out adventuring,

they must spend money for

a place to

stay, food, clothing, and

amenities ? all

expenses that are not reflected

in buying

equipment for adventures.

Some rules

assume that the more experienced

a character

is, the more money he will

spend.

This is almost universally

true, but still

somewhat inaccurate; though

there is a

tendency in most people

(and characters)

to spend more when one has

more to

spend, an adventurer?s rise

in income can

often far outstrip his expenditures.

Adventurers will always

have to pay a

minimum amount for upkeep,

with additions

according to the extent

of largesse

and luxury they wish to

enjoy. Armor

and weapon repairs, oil

and rations, and

other matters of equipment

replacement,

often ignored by players,

can be subsumed

in upkeep. And the more

expensive

a city?s prices are, the

higher upkeep

costs will be for residents

in the city. Here

is where the idea of local

inflation ? the

?gold rush boom town? with

very high

prices for ordinary goods

? can come

into play.

Henchmen

and hired help:

Along with

personal upkeep comes payments

to

henchmen and loyal followers,

including

(but not limited to) their

upkeep. This

total expense can be much

greater than

personal costs.

Novice and near-novice adventurers

are

unlikely to have such expenses,

but veterans

who may wish to hire skilled

craftsmen must pay what

the market

demands, regardless of the

?list price?

given for a service in the

rulebook. If only

one armorer in town can

make plate, and

several adventurers or lords

want to hire

him, the armorer

may charge an unusually

high fee.

(It should be noted for medievalists,

however, that in the Middle

Ages many

fees were set by a guild

or by the city

government and could not

be exceeded.

Supply and demand, as we

know it, did

not operate to change prices,

though it

might lead to a devaluation

of coinage

through reduction of the

metal content.)

Adventurers' followers and

henchmen, <not all followers have to be paid: check this>

if they're to remain loyal,

must be very

well paid; otherwise, many

will strike out

on their own. A character

who owns a

stronghold, even a simple

blockhouse

with tower, will have to

pay troops and

other skilled personnel

to garrison it.

They must be paid well enough

to

remain loyal, or the character

may find

when he returns from an

adventure that

he's excluded from his stronghold,

or that

it has been sacked, by the

garrison.

Acquiring

a stronghold: Perhaps the

greatest expense any adventurer

will face

is the cost of buying or

constructing

a

personal stronghold. An

adventurer may

buy or build several strongholds

in the

course of a long, successful

career. The

first may be a small tower,

or just a stone

house or villa, either in

or near a town.

Unless he has obtained a

large grant of

land as well, the character

may prefer to

move to another area to

build a full-scale

castle, rather than expand

his single

tower. And later he may

trade territories

(not uncommon in the Middle

Ages) or

find a better place to build

his master

"festung" in which to spend

his remaining

years. Such great stone

edifices are

extremely expensive, especially

if the

adventurer wants it built

rapidly rather

than over the course of

five years.

Moreover, expenses do not

stop when the

stronghold is completed.

Maintenance

costs, both for material

and personnel, are

anything but negligible

? and the older

the stronghold, the more

maintenance of

the structure will cost.

If life is too easy for characters

while

they stay in a town, they?ll

have no incentive

to obtain a stronghold.

The more

they?re harried by thieves,

assassins, punk

sword-slingers looking for

a reputation,

and so on, the more they?ll

look on

spending money for a stronghold

as a

gain, not a loss.

Religion:

Religion should drain a significant

sum from adventurers, staying

more or less proportional

as income rises.

In most fantasy worlds the

gods are real,

and if not omnipresent,

they at least affect

the world through manipulation

of followers

and minions. Most adventurers

will actively worship one

or more gods, if

only "just in case, you

know . . ." Active

worship entails contributions,

if not

tithes (10% of all income)

or offerings of

animals

and goods of the worshipper.

And if the local temple

is destroyed, the

wealthy worshippers (that

is, the adventurers)

will be expected to provide

money

to rebuild it.

In the medieval or the modern

world, citizens of a town

are expected to

pay taxes according to the

value of their

property -- including money,

in the

Middle Ages -- and non-citizens

are

targets for special levies,

unless the town

is particularly eager to

persuade the foreigners

to stay. This eagerness

is conceivable

if the town is threatened

from the

outside and the foreigners

(adventurers)

offer the best defense.

A character's stronghold

may be taxed

by the overlord of the area.

If the character

holds the land in fief,

he may be

exempted from many taxes,

but on the

other hand he'll have feudal

obligations

to his overlord. This often

includes the

providing of troops, which

means that

the character must hire

extra men, and

pay for upkeep of troops

on campaign,

even if he doesn't go himself.

This will be

true whether the troops

take an active

part in the campaign or

march on a crusade

to a faraway land.

Pets:

The animal companion(s) of an

adventurer, especially if

they are big pets,

can be a drain on the character's

income

as he pays for housing,

training,

and

feeding the creature. Perhaps

outside of

town the fighter's pet griffon

or hippogriff

can feed on kills ? provided

it

doesn?t take down some farmer?s

domestic

animal ? but when the fighter

stays in

town, he?ll need to buy

animals to feed

his mount.

Training young animals may

cost even

more than feeding them,

because the ability

to train is so rare and

the act requires

so much time. But the biggest

expense of

all could be buying the

young animal (or

egg) in the first place.

Encourage players

to have pets, if only well

trained (and

thus expensive) war dogs.

Sooner or later

the pet will be killed,

and in the meantime

it may cause much amusement

for

the referee, and difficulty

for the owner.

On the other hand, if his

pet saves his life

just once, the owner will

think it well

worth the expense.

Equipment:

Not all equipment is

created equal. That is,

some suits of (nonmagical)

armor are more protective

than

others, some swords are

stronger than

others and hold an edge

better, and so on.

The "ordinary" price for

a piece of

equipment given in rulebooks

could not

be for the highest quality

product. Consequently,

another way to bleed funds

from characters is to offer

the opportunity

to buy exceptional, but

non-magical,

armor

and weapons. The best

of this

might even be equivalent

in protection or

striking power to the weakest

sort of magical

armor and weapons; you,

as the referee,

must judge where the line

is drawn.

Or, if you prefer, you may

simply make

"ordinary" equipment somewhat

unsafe

to use, in order to encourage

PCs

to buy better materials.

For example,

a dice roll can be taken

at the end of

each adventure (or each

battle) to determine

whether armor or weapons

have

broken or worn out -- and

more expensive

equipment wears out much

less

often. Or, stipulate that

when a player

rolls a 1 when attacking,

there is a chance

that his weapon breaks,

and when an

attacker rolls a 20 (or

100) there is a

chance that the target's

armor is damaged

and his armor class is lessened

by one.

The size of this "chance

to be damaged"

will vary with the quality

of the equipment.

The players can either periodically

buy or repair cheap stuff,

or they can buy

high-quality products and

rest more

easily.

Of course, a referee could

have someone

sell magical equipment to

characters, but

in most worlds the price

should be so

prohibitive that no adventurer

could

afford anything but a trade

of magic

items, rather than a purchase.

Who

would be crazy enough to

sell a permanently

endowed magic item, such

as a

sword or shield?

One-use

magic: While permanent

magic items such as armor

will not be

available for purchase in

most campaigns,

except between players,

one-use

magic will be more plentiful.

Alchemists

manufacture potions to sell

them, since

they can't use most potions

themselves.

Retired magicians may make

a living

creating and selling scrolls

and recharging

some magic items.

Allowing for the purchase

of "one-use

magic? can be a wonderful

way to drain

money from adventurers without

unbalancing

the game; in fact, it offers

players

one more way to make a ?good

move? in

the game by purchasing the

most important

types of one-use items,

such as scrolls

for healing or neutralizing

poisons.

If a character finds a fairly

good magic

item, such as a wand of

magic missiles or

a wand of weak fireballs,

he can hardly

afford to allow the thing

to run out of

charges, yet he?ll probably

use it frequently.

Consequently, he?ll be willing

to

pay out large sums to a

magician to restore

some charges to the item.

It?s not

unknown for several members

of a group

of adventurers to contribute

money

toward recharging a wand

owned by one

of them, because the wand

helped all of

them survive.

Information:

The "facts of the matter"

should be a valuable commodity

in the campaign, something characters

will buy

at a high price. This information

can

come in many forms, from

stories told in

taverns (?Have another drink

and tell me

more?) to accounts told

by rumormongers

and oral historians, to

the purchase

of ancient books and the

expertise

of sages. Education and

training for the

adventurers themselves is

a form of

information which will cost

significant

sums early in a campaign;

later, adventurers

will teach one another their

skills,

and will learn few new ones.

The more accurate a piece

of information

is, the more it should cost.

Experts,

especially, are always expensive

? think

of a sage as the fantasy

equivalent of a

?consultant,? with the high

fees that

occupation demands, rather

than the

equivalent of a reference

librarian or a

university instructor. And

although there

were no detectives in medieval

times, it is

possible that someone would

set himself

up in the ?information gathering?

business

? not quite a detective,

but not a spy

either. Such persons would

charge high

fees because their service

is nearly unique.

Politics:

It is almost impossible to

become a wealthy, successful

adventurer

without getting involved

in politics:

wealth && prestige

bring enemies and

hangers-on. The more a character

participates

in politics, the more it

will cost to

acquire and retain supporters,

to obtain

info, to bribe.

Well-known adventurers may

be

expected to spend a season

at the court of

the ruler of the region.

The travel,

retinue, finery, and gifts

this entails will

not be balanced by any monetary

gain,

although the increase in

prestige &&

favor may help the character

later.

Tournaments (jousts

&& duels) can be

expensive for adventurers

who are

expected to participate

in such events,

although in some areas the

prizes offered

may more than offset the

cost.

And if a character is really

serious

about politics, he may have

to bankroll a

private army!

<cf. The Politician>

Bribes:

This is a way to soak up money

in an accumulation of small

amounts.

Most readers will have heard

of countries

in which every official,

minor or otherwise,

expects a bribe in return

for

accomplishing what is nominally

his

everyday job. Why can't

a fantasy society

be afflicted with the same

inefficiency--

It's a matter of the size

of the bureaucracy,

the way it's recruited,

and the expectations

of the society.

<cf. The Bureaucrat>

Research:

Magical research, whether to

discover new

spells or to determine the

nature of found magic items,

takes

money. Don't let characters

pay a meager

sum in order to find out

everything there

is to know about a newly

obtained item.

Bleed their money away,

giving a little

more information for each

input of

funds. After all, magicians

are rare and

should be paid appropriately

for their

valuable research time.

Of course, player characters

may decide

not to pay, but that's their

choice; it may

be possible to discover

the relevant

information through rumors,

libraries,

and knowledgeable non-magicians.

The more complex a magic

item is, the

more characters will have

to pay to

determine exactly what it

does. More than

one level of performance,

or more than

one power, is desirable

in an item ? even

items with (unbeknownst

to the player

characters) only one power

? so that

players may continue to

pay money in an

attempt to learn about additional

powers

of an item long after all

of its powers and

levels of ability have actually

been

revealed.

For example, one researcher

may be able

to determine the powers

of a wand. Another

research expert may know

a command word,

not necessarily relating

to the known power. Further research

may reveal another command

word , not necessarily relating

to the known power. Further

research

may reveal another command

word and a

second power, perhaps a

variation of the

first one. And, the wand

may be found to

occasionally weaken the

user; finding out

how to avoid that effect

-- or even if there

is a way to avoid it --

would cost even

more than finding out about

one of the

wand's beneficial aspects.

Investments:

Bad investments will cost

characters large sums. There

ought to be

a few good investments available,

but

most should be bad -- just

as in the modern

world.

Ways to spend invested money

may include schemes to manufacture

new

inventions, property deals,

money lending,

and most likely, mercantile

ventures.

While a smart mercantile

deal may net a

character a return of more

than 100% or

200%, most will result in

a poor return or

a loss. Characters may attempt

to literally

?protect their investments?

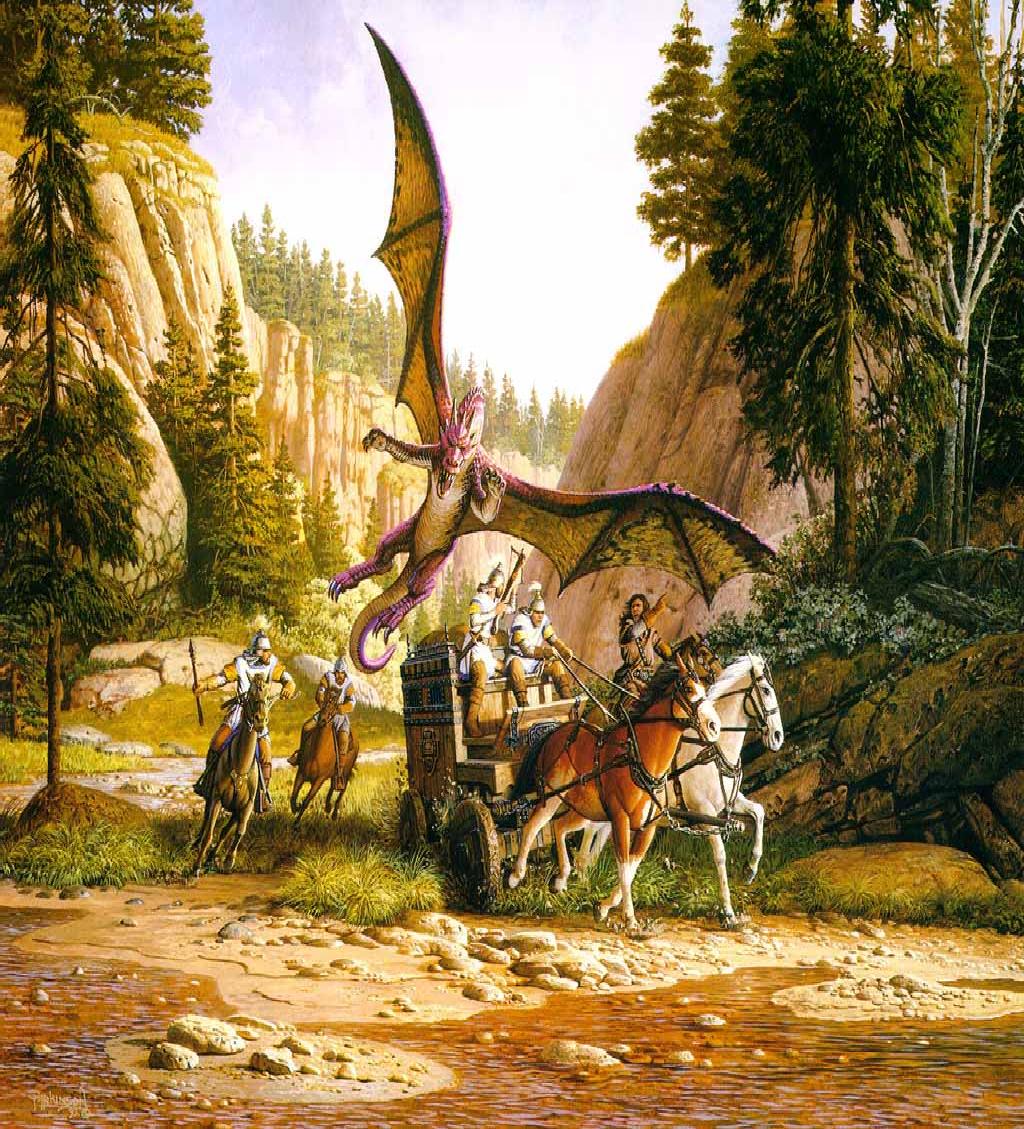

by accompanying

a vehicle or caravan picking

up

or delivering goods, thereby

giving the

referee opportunities to

create miniadventures

connected with the trade

routes and destinations.

Gambling:

This is a good way to

separate incautious characters

from their

fortunes, in the long run.

Just make sure

the odds favor the house

? if the game

isn?t actually fixed ? and

remember that

a really big winner may

make enemies of

the owners of the gambling

establishment,

or of the losers in a private

game.

A referee can encourage

gambling by

making participation a matter

of prestige

in the locale, and by providing

means of

obtaining information ?

rumors, at the

least ? unique to the gambling

establishment(

s). If you challenge the

?manhood

? (or ?womanhood?) of the

player

characters in connection

with gambling,

some of them will respond

unwisely ?

that is, they will gamble

to ?prove?

themselves.

Small

treasures, big spenders

The more

opportunities PCs

have to spend money,

in small amounts or

large, the more they'll

spend. Some combination

of the methods described

above

should allow the referee

to reduce the fortunes

of all but the most miserly

adventurers.

But the most important single

method

of doing this is to make

treasures small so

that characters can't accumulate

large fortunes.

Whether this stringency

fits the

"heroic" mold is a matter

that only each

referee and the players

in his or her campaign

can decide.

The vicarious

participator

Take the middle ground in

role-playing style

by Lewis Pulsipher

In the early days of fantasy role-playing

(FRP) gaming,

many players did not role-play

in any significant sense of the word;

that is,

they did not pretend or imagine that they

were in a real world different from our own.

Instead, they made a farce

out of FRP, and their characters tended

to

act like thugs || gangsters, if not fools.

Pursuit of power, without regard for any-

thing else, was typical.

In reaction && rebuttal to this,

some

players went to the other extreme. They

believed that characters, through their

players, should imagine themselves as

fulfilling a role in the real world, and

further declared that each character

should be a personality completely sepa-

rate from the player, so that the player

becomes more of an actor than a partici-

pant in a game.

For several years these

people were voices crying out in the wil-

derness, but as more people gained FRP

experience or heard about this “improvi-

sational theater” (or “persona-creator”)

school of role-playing, and as the more

articulate and vociferous of the “persona”

extremists found an audience for their

views, this extreme attitude about role-

playing has spread so widely that it,

instead of not role-playing at all, seems

to

have become the standard.

Unfortunately, because initially they

had to express their views about role-

playing with maximum emphasis just to

be listened to, many of the people in

this

second group have become intolerant of

other views. One occasionally runs into

remarks at conventions or in articles

which disparage anyone who does not

create an elaborate persona for each of

his

characters, each different from his own

personality. The most hard-line advocates

of this school of thought refuse to believe

that there is any other “proper” way to

play, and they measure the skill of a

role-

playing gamer in accordance with how

closely he or she meets their notions

of

role-playing as theater.

There is a third group, with an attitude

that lies between the power-mad, thug-

character players on one hand and the

persona-creators on the other. The view-

point of these people, who may be called

“vicarious participators,” reflects the

original intent of role-playing gaming.

They (and I number myself among them)

believe that the point of a role-playing

game is to put oneself into a situation

one could never experience in the real

world, and to react as the player would

38J

like to think he would react in similar

circumstances.

In other words, the game lets me do the

things I’d like to think I would do if

I

were a wizard, or if I were a fighter,

or

perhaps, even, if I decided to take the

evil

path. Consequently, it would be foolish

for me to create a personality quite differ-

ent from my own, because it would no

longer be me. The game is not a matter

of

“Sir Stalwart does so-and-so” but “I do

so-and-so.” In my imagination, I am the

one who might get killed — not some

paper construct, however elaborate it

may

be. (Of course, because these are games

played by people with adult mentality

—

even if not of adult age — no one ever

becomes overinvolved emotionally.)

Notice, also, that I didn’t say “as I

would act,” but “as I would like to think

I would act.” Few FRP gamers are made

of the stuff of heroes, but we like to

think

we are when we play the game. The game

allows us to live out our fantasies about

being heroic, or saintly, or evil, although

we in our personal lives will never reach

nor probably aspire to any of these

extremes. As one player put it, if he

were

actually in a dungeon he’d be scared silly

and would flee in utter panic — but his

character does not, because the character

can have attributes (courage, in this

case)

which the player does not have.

The difference between this view and

the persona-creator’s view is fairly clear-

cut, though it would be hard to define

a

line dividing one style from the other.

The vicarious participator lives an adven-

ture through his character, which tends

to

be a lot like he is himself. But he accepts

that his character must undergo some

changes in attributes and personality

from the player’s, whether these changes

are imposed by the player himself, by

the

game rules, or by the nature of the ref-

eree’s “world,” to help him enjoy events

he could never experience in the real

world.

For example, he will accept the

requirements of an extremely good

alignment and crusading zeal of a

paladin, or the requirements of a charac-

ter who is evil, or even a character of

the

opposite sex. To him, the question is

“What would I (like to) do if I were such-

and-such in a fantasy world?”

The persona-creator, on the other

hand, places himself at a distance from

his character, regarding it as a separate

entity almost with a life of its own.

He is

not interested in what he would do, but

in what a creature of such-and-such race,

intelligence, likes, dislikes, etc., would

do

in a given situation. If his character

dies,

his reaction is not overly emotional,

though he’ll certainly regret the loss

of all

the work he put into the character.

The difference between the two styles

is

manifested in many small ways. For

example, a persona-creator playing a

character of low intelligence will play

dumb. If he has a good idea, he probably

won’t mention it to the other players,

since his character wouldn’t have thought

of it. A participator, on the other hand,

doesn’t always care what his character’s

numbers happen to be. It’s really him

in

there, anyway, and he’ll use his own

brain and other faculties to the fullest

to

keep his character alive and accomplish

his goals.

This difference can be generalized to

show the attitudes of the two types of

role-players to the aspect of luck in

char-

acter generation. The persona-creators

are

not much concerned with being able to

choose aspects of the personality of their

character. In a sense, they try to be

like

the most versatile film and stage actors,

who can play any role well. Consequently

they would not mind, and might even

prefer, playing a game like Chivalry &

Sorcery,

in which virtually everything

about a character — alignment, race, even

horoscope — is determined by dice rolls.

On the other hand, vicarious participa-

tors want to have some choice in the role

they play. They prefer an activity such

as

the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS®

game,

in which only the ability scores are

determined by chance, while race, align-

ment, social status, and so on are largely

matters of choice. The participators

resemble film or stage actors who have

specialized in a type of role; in this

case,

they specialize in being some variant

of

their idealization of themselves.

As stated before, one cannot draw a def-

inite line between the two styles. As

par-

ticipators play more characters in differ-

ent situations, they begin to approach

the

persona-creators in effect. They play

many different roles, increasingly differ-

ent from their original notion. Many

persona-creators, on the other hand, do

not care to play a persona they have not

created themselves; that is, they put

much

of themselves into the character. There

is

still a fundamental difference in attitude,

however, between “I am doing it” and

“This character is doing it.” Persona-

creators, even of this limited sort, have

been known to write stories about their

characters and develop plot lines which

do not arise from any game or any ref-

eree’s action. Participators would never

bother with this.

How does the vicarious player differ

from the power/thug gamer? Again, there

is no sharp dividing line between them.

In some cases the power/thug players are

simply indulging in infantile fantasies

—

they haven’t matured yet, or they don’t

bring their maturity to their gaming ses-

sions. Vicarious players realize that

in

this and every world there must be limita-

tions on what a person can do, but those

limitations are different in the game

than

they are in real life. For example, I

have

never met a participator who could

believe in (or tolerate) a situation in

which mortal characters defeat gods. Yet

such scenarios occur frequently in

“power” games. The power/thug players

are quite content to ignore all limitations

on their characters, and they find referees

who allow or encourage them to act in

this manner. Some role-players sneer at

this attitude, but many people enjoy play-

ing this way. However, while persona-

creators and vicarious players can co-exist

in a campaign, provided they are aware

of

their differences, neither type can practi-

cally co-exist with the thugs.

The most important point I want to

make is that there is nothing superior

about the persona-creation method of

role-playing. Vicarious participation

is

neither less mature, nor less intelligent,

nor less “true blue” than persona-

creation, though all these claims have

been made at times. Persona-creators

should accept that many players simply

do not want to become actors. Refereeing

requires quite enough acting for most

of

us, for the referee must separate himself

completely from his non-player charac-

ters or he cannot be objective and impar-

tial — he must be a persona-creator in

order to be a good referee. Perhaps this

is

the clearest indication that persona-

creation is no better than vicarious partic-

ipation: Many excellent referees, who

are

necessarily excellent persona-creators,

nonetheless prefer vicarious participation

when they play. The vicarious style is

a

matter of choice, not of inability to

act.

The Golem's Craft

Want to build a golem?

It isn't easy . . .

by John C. Bunnell

Charybdis

PURPLE DRAGON